SHAME ON USA AND CHINA ON THEIR BRAGGING ON CLIMATE CHANGE AND IVORY - THE WORLD'S WORST OFFENDERS AND $$$$ BUYERS OF SO MUCH DEVASTATION 4 PROFIT.... u stand in front of the world.... like u are heroes.... and shame humanity.... we are bright, educated and savvy..... shame on u.... humanity matters.... nature matters.... decency matters....Canada- we will fix our environment... and our cultures... and our humanity... BUT DON'T EMBARRASS CANADA BY USING USA-CHINA AND/OR UNITED NATIONS.... please..... it's disgusting... elephants and lost nature's protectors and survivors- they matter... imho... tears and prayers

Over a ton of American Ivory Jewellery

CANADA'S ELMER THE SAFETY ELEPHANT

News / USA

Americans Declared Major Ivory Consumers

June 12, 2014 1:27 PM

China embarked this year on a major campaign to persuade ivory lovers to get out of the habit of buying ivory carvings. That was big news several months ago when television cameras showed bulldozers in Guangzhou crushing tons of elephant tusks confiscated from smugglers.

The campaign in the world’s biggest ivory market continues with the broadcast of public service announcements showing the towering seven-and-a-half foot tall figure of former National Basketball Association player Yao Ming looking down with sadness at a butchered elephant carcass on a Kenya savannah.

Brooke Darby says there should be more campaigns like China’s in many countries. Darby is deputy assistant secretary of state for international narcotics and law enforcement, one of many U.S. agencies that has taken on the poaching issue as part of a global crime wave.

Where did that piece of ivory come from?

“I think we focus a lot on the problem of demand being focused in Asia but, in fact, the United States is a major consumer of wildlife products. We have some work to do as well. We’re right up there.

So when 17 U.S. federal agencies were told to work together on the problem, they learned something about the naivete of American consumers.

“One of the things we’ve learned is that often consumers don’t realize that the animal dies when the tusks or horn are taken,” Darby says. “And, therefore, these trinkets that they have picked up that are made of ivory actually were a function of an animal dying in the field."

That’s important when it is revealed that the United States buys lots of ivory from those dead elephants.

Buying on Broadway and the Internet

John Calvelli of the Wildlife Conservation Society says the United States is one of the largest users of ivory in the world. Probably one of the top five.

“I will tell you, take a walk on the streets of New York and you will find ivory for sale,” says Calvelli. “And you realize that studies have been done that show that probably about one-third of the ivory in the United States comes from illegally killed elephants, so the domestic illegal market is masking the illegal market.”

For many years, it was legal to trade ivory that came from elephants before the United States signed a treaty designed to suppress the trade. That did not make much difference.

John Webb, a former prosecutor of wildlife crimes for the U.S. Justice Department and a member of the President’s Advisory Council on Wildlife Trafficking, confirms the United States is a huge market for ivory sales fueled by Internet sales.

New U.S. ban extends to antiques

For years, U.S. laws prohibited the sale of ivory taken from elephants that were killed after the CITES treaty was signed in 1973. But it was difficult to tell the age of the ivory in a store window. Calvelli says there are efforts to pass a moratorium on all ivory sales in New York State.

But greater impact may come from President Obama’s announcement of a ban on all ivory sales within the United States. The new regulation, which prohibits the trade of any item that contains ivory of any age, is being criticized by antique dealers. If strictly enforced, it could make the sale of certain chess pieces, the handles of revolvers, letter openers, piano keys and the bows of some violins.

Since President Obama issued an executive order creating a 17-agency task force to combat wildlife trafficking, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has prosecuted several cases of black market trade in rhino horns, for example. A Canadian art import and export business doing business in Cameroon and the United States was fined $100,000 for shipping parts of 21 elephants to Ohio.

Building regional enforcement networks

The United States government has become a leader in international efforts to end poaching and international shipment and sales of illegal ivory.

Under a new transnational crime program, the U.S. government offered a $1 million reward for information leading to the arrest of Vixay Keosavang, a Loatian and the kingpin of a major wildlife trafficking network.

The U.S. Agency for International Development has funded regional alliances of conservation and law enforcement agencies such as Asia’s Regional Response to Endangered Species Trafficking (ARREST) in Bangkok, where there have been some successful busts. Webb has watched the growth of these regional networks with great interest.

“Cops don’t trust each other, I mean that’s the bottom line,” says Webb. “So one of the reasons you create these new wildlife enforcement networks is its much easier to work with somebody who you’ve met face to face and know than it is some faceless law enforcement official from a foreign country.”

How long will it take?

More attention is being paid to judicial systems in African countries where wildlife crimes may - or may not - be punished. Webb declares that the government officials and courts of many African countries represent the biggest challenge to the termination of the poaching of wildlife.

Recent thinking now brings together many forces to force a decline in poaching in Africa’s parks: law enforcement, conservation, economic development, government and court reform, and more.

The challenge of saving Africa’s elephants is likely more complex than anyone yet realizes. Varun Vira, an analyst at C4ADS and co-author of Ivory’s Curse: The Militarization and Professionalization of Poaching.

Vira cites the work of the World Bank and others who draw a correlation between poaching and the long-term impacts of the poverty, hunger and infant mortality. These are major issues that haunt vast populations who share Africa with its remaining herds of elephants.

This view supports the notion that the soluton to Africa’s elephant poaching crisis may only be reached by solving many other social, economic and political problems that challenge African mostly rural countries. Some of these observers say that poaching has been going on in Africa for centuries.

The campaign in the world’s biggest ivory market continues with the broadcast of public service announcements showing the towering seven-and-a-half foot tall figure of former National Basketball Association player Yao Ming looking down with sadness at a butchered elephant carcass on a Kenya savannah.

Brooke Darby says there should be more campaigns like China’s in many countries. Darby is deputy assistant secretary of state for international narcotics and law enforcement, one of many U.S. agencies that has taken on the poaching issue as part of a global crime wave.

Where did that piece of ivory come from?

“I think we focus a lot on the problem of demand being focused in Asia but, in fact, the United States is a major consumer of wildlife products. We have some work to do as well. We’re right up there.

U.S. experts discuss America's challenges with poached ivory

So when 17 U.S. federal agencies were told to work together on the problem, they learned something about the naivete of American consumers.

“One of the things we’ve learned is that often consumers don’t realize that the animal dies when the tusks or horn are taken,” Darby says. “And, therefore, these trinkets that they have picked up that are made of ivory actually were a function of an animal dying in the field."

That’s important when it is revealed that the United States buys lots of ivory from those dead elephants.

Decorative carved ivory was piled high for destruction at the National Wildlife Property Repository at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Commerce City, Colorado in November, 2013. It was a first public step to curb the U.S. love of ivory piano keys, letter openers, chess pieces and jewelry.

Decorative carved ivory was piled high for destruction at the National Wildlife Property Repository at Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge in Commerce City, Colorado in November, 2013. It was a first public step to curb the U.S. love of ivory piano keys, letter openers, chess pieces and jewelry. Media coverage of the Fish and Widllife Service crush was designed to call for an end to domestic sales of antique and new ivory. 'These trinkets ... actually were a function of an animal dying in the field," said a State Department official. "We have some work to do."

Media coverage of the Fish and Widllife Service crush was designed to call for an end to domestic sales of antique and new ivory. 'These trinkets ... actually were a function of an animal dying in the field," said a State Department official. "We have some work to do." More than 50 nations gathered in February with Prince Charles and British Foreign Secretary William Hague to sign a pledge to prevent poaching. The hosts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Conference in London said tens of thousands of elephants and more than 1,000 rhinos were killed last year.

More than 50 nations gathered in February with Prince Charles and British Foreign Secretary William Hague to sign a pledge to prevent poaching. The hosts of the Illegal Wildlife Trade Conference in London said tens of thousands of elephants and more than 1,000 rhinos were killed last year.

Former National Basketball Association star Yao Ming was the headliner in an film documentary that appeals to Chinese consumers to stop collecting ivory. In his anti-poaching campaign, Ming was filmed viewing the carcass of an elephant killed for its tusks in Kenya's Samburu region.

Former National Basketball Association star Yao Ming was the headliner in an film documentary that appeals to Chinese consumers to stop collecting ivory. In his anti-poaching campaign, Ming was filmed viewing the carcass of an elephant killed for its tusks in Kenya's Samburu region.

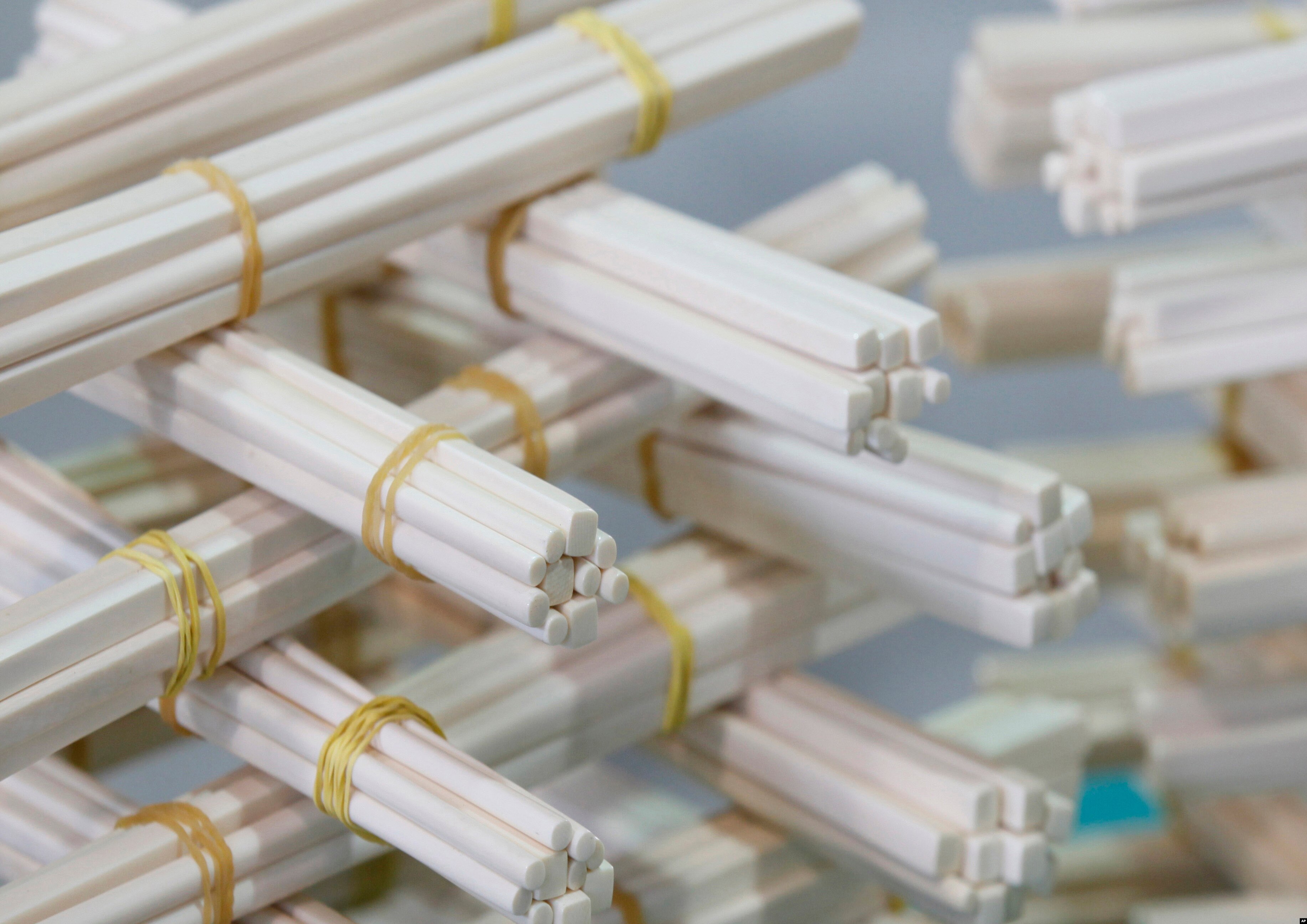

Chopsticks carved from an elephant's ivory tusks are still popular in China. Customs agents in Hong Kong seized 758 chopsticks, 127 bracelets, and 33 rhino horns on November, 2011. The street value was estimated at $2 million.

Chopsticks carved from an elephant's ivory tusks are still popular in China. Customs agents in Hong Kong seized 758 chopsticks, 127 bracelets, and 33 rhino horns on November, 2011. The street value was estimated at $2 million.

Kenya Wildlife Service officers hold black rhino horns that were part of a shipment of 16 elephant tusks taken from smugglers trying to fly them to Bangkok in 2009.

Kenya Wildlife Service officers hold black rhino horns that were part of a shipment of 16 elephant tusks taken from smugglers trying to fly them to Bangkok in 2009. Nguyen Huong Giang demonstrated in her Hanoi apartment in 2012 how to grind rhinoceros horn with water to mix a liquid she drinks to reduce the effects of too much drinking the night before or alleviating her seasonal allergies. Others in Vietnam think it will cure cancer and other debilitating or fatal illnesses.

Nguyen Huong Giang demonstrated in her Hanoi apartment in 2012 how to grind rhinoceros horn with water to mix a liquid she drinks to reduce the effects of too much drinking the night before or alleviating her seasonal allergies. Others in Vietnam think it will cure cancer and other debilitating or fatal illnesses.

The technician at the controls of a Hong Kong chemical treatment plant control room monitors the incineration of 28 tons of ivory in March, 2014. The process could take a year, according to some officials.

The technician at the controls of a Hong Kong chemical treatment plant control room monitors the incineration of 28 tons of ivory in March, 2014. The process could take a year, according to some officials. Hunters buy special permits from some African governments to hunt large wildlife on a restricted basis. Fees sometimes help fund animal conservation progrems. When the Dallas Safari Club auctioned a permit to hunt an endangered black rhino, the FBI investigated death threat claims. The club's executive director, Ben Carter, (right), was photographed with a wildlife artist at the club's January, 2014 show.

Hunters buy special permits from some African governments to hunt large wildlife on a restricted basis. Fees sometimes help fund animal conservation progrems. When the Dallas Safari Club auctioned a permit to hunt an endangered black rhino, the FBI investigated death threat claims. The club's executive director, Ben Carter, (right), was photographed with a wildlife artist at the club's January, 2014 show.

Buying on Broadway and the Internet

John Calvelli of the Wildlife Conservation Society says the United States is one of the largest users of ivory in the world. Probably one of the top five.

“I will tell you, take a walk on the streets of New York and you will find ivory for sale,” says Calvelli. “And you realize that studies have been done that show that probably about one-third of the ivory in the United States comes from illegally killed elephants, so the domestic illegal market is masking the illegal market.”

For many years, it was legal to trade ivory that came from elephants before the United States signed a treaty designed to suppress the trade. That did not make much difference.

John Webb, a former prosecutor of wildlife crimes for the U.S. Justice Department and a member of the President’s Advisory Council on Wildlife Trafficking, confirms the United States is a huge market for ivory sales fueled by Internet sales.

New U.S. ban extends to antiques

For years, U.S. laws prohibited the sale of ivory taken from elephants that were killed after the CITES treaty was signed in 1973. But it was difficult to tell the age of the ivory in a store window. Calvelli says there are efforts to pass a moratorium on all ivory sales in New York State.

But greater impact may come from President Obama’s announcement of a ban on all ivory sales within the United States. The new regulation, which prohibits the trade of any item that contains ivory of any age, is being criticized by antique dealers. If strictly enforced, it could make the sale of certain chess pieces, the handles of revolvers, letter openers, piano keys and the bows of some violins.

Since President Obama issued an executive order creating a 17-agency task force to combat wildlife trafficking, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has prosecuted several cases of black market trade in rhino horns, for example. A Canadian art import and export business doing business in Cameroon and the United States was fined $100,000 for shipping parts of 21 elephants to Ohio.

Building regional enforcement networks

The United States government has become a leader in international efforts to end poaching and international shipment and sales of illegal ivory.

Under a new transnational crime program, the U.S. government offered a $1 million reward for information leading to the arrest of Vixay Keosavang, a Loatian and the kingpin of a major wildlife trafficking network.

The U.S. Agency for International Development has funded regional alliances of conservation and law enforcement agencies such as Asia’s Regional Response to Endangered Species Trafficking (ARREST) in Bangkok, where there have been some successful busts. Webb has watched the growth of these regional networks with great interest.

“Cops don’t trust each other, I mean that’s the bottom line,” says Webb. “So one of the reasons you create these new wildlife enforcement networks is its much easier to work with somebody who you’ve met face to face and know than it is some faceless law enforcement official from a foreign country.”

How long will it take?

More attention is being paid to judicial systems in African countries where wildlife crimes may - or may not - be punished. Webb declares that the government officials and courts of many African countries represent the biggest challenge to the termination of the poaching of wildlife.

Recent thinking now brings together many forces to force a decline in poaching in Africa’s parks: law enforcement, conservation, economic development, government and court reform, and more.

The challenge of saving Africa’s elephants is likely more complex than anyone yet realizes. Varun Vira, an analyst at C4ADS and co-author of Ivory’s Curse: The Militarization and Professionalization of Poaching.

Vira cites the work of the World Bank and others who draw a correlation between poaching and the long-term impacts of the poverty, hunger and infant mortality. These are major issues that haunt vast populations who share Africa with its remaining herds of elephants.

This view supports the notion that the soluton to Africa’s elephant poaching crisis may only be reached by solving many other social, economic and political problems that challenge African mostly rural countries. Some of these observers say that poaching has been going on in Africa for centuries.

global march for elephants an rhinos | Tumblr

www.tumblr.com/tagged/Global-march-for-Elephants-an-Rhinos

The ivory trade is

driven by greed, superstitions, lack of education and individuals who think

their status is ... by ivory. China and the USA are the worst offenders.

June | 2011 | 2ndlook

2ndlook.wordpress.com/2011/06/

Jun 15, 2011 - (Cartoon by Kirish

Bhatt; courtesy - bamulahija.blogspot.com). ..... US-China are likely

to remain large producer-importers for some more time. .... scale, does Britain

admit that they were here to loot and plunder India? ..... Was it fossil ivory, of the mammoth type, or the modern African or Asian elephant tusk.

----------

Great Elephant Documentary! (Environmental) - 'Large Matter' - A MUST WATCH!!!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_detailpage&v=QTKvZYneXd0

-------

Ironically ivory trade is permitted in the US and while it involves mostly

old pre-ban ivory, like the situation in China, the legal trade is being used

as a cover for a significant amount of illegal trade. Although China is ranked

as the top consumer of illegal ivory, the US is considered the second largest

market in the world.

US

wakes up to illegal ivory trade

The plight of elephants is in the spotlight thanks to Hillary Clinton,

the courts and the American public

Park ranger Benjamin Kalimutima Lulimba with the skull of an elephant

killed for its ivory. Security forces in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

have been accused of complicity in attacks on rangers by marauding militias

exploiting animals and minerals. Photograph: Francesca Tosarelli

African elephants have been thrust into the global spotlight by four

events in the US: the Clinton

Global Initiative last week, the March for Elephants

on 4 October, the sentencing

of American ivory trafficker Victor Gordon on 7 October [update: this has

been rescheduled to February 2014], and the crushing

of 6 tons of US-held ivory in Denver on 8 October.

At the Clinton Global initiative, seven African nations joined Hillary

and Chelsea Clinton in a commitment to end the slaughter of elephants by

banning domestic trade in ivory, stopping the killing of elephants, the

trafficking of ivory, and the demand for ivory. The countries were Botswana,

Cote D'Ivoire, Gabon, Kenya, South Sudan, Malawi and

Uganda.

Richard Leakey, founder of WildlifeDirect

and the man who is credited with saving elephants from extinction by

engineering the first ever and most iconic bonfire of ivory in 1989, said:

"I congratulate Senator Clinton for her actions and commitment and

am all for each nation taking responsibility for saving one of the world's most

magnificent animals. I hope that the USA will follow Africa and ban domestic trade in

ivory … and provide support for strategic African initiatives to save elephants

and stop the poaching."

A study by WildlifeDirect reveals that fewer than 5% of convictions for wildlife crimes lead to jail

sentences. Not surprisingly, suspected elephant killers and ivory traffickers

plead guilty in order to hasten the case and gain a light sentence. Most cases

last only 24 hours and most convictions result in a fine of $100-$300. The

laxity of the courts had been driving impunity and encouraging poaching, but

now the magistrates are delivering jail sentences of three to five years.

Any time in jail is bad in Kenya, but WildlifeDirect says this is still

not enough and is pushing for seizure of assets, prosecution under the

Organised crime Act and Economic Crimes Act, and minimum jail sentences of 15

years in proposed new legislation that is expected to pass in coming weeks.

Next up is the Elephant March. Millions of people are expected to

participate on 4 October in cities around the world. This is one of the things

that citizens around the world can do to demonstrate their concern about the

elephant slaughter.

Later, the US Fish and Wildlife Service will make an international

statement by crushing six tons of elephant ivory seized by its special agents

and wildlife inspectors for violations of US wildlife laws.

All this attention to elephants is well-deserved. Ivory is leaving

Africa at an unprecedented rate, part of a surge in poaching that could lead to

the extinction of the elephant within 10 years if it is not halted. But it

isn't just about elephants.

The illegal trade in ivory is fueling conflicts and terrorism including

the deadly attacks on a shopping mall in Kenya, and the US is not exempt from

the problem.

Ironically ivory trade is permitted in the US and while it involves

mostly old pre-ban ivory, like the situation in China, the legal trade is being

used as a cover for a significant amount of illegal trade. Although China is

ranked as the top consumer of illegal ivory, the US is considered the second

largest market in the world.

The ivory crush will include ivory items seized last year when the US

Fish and Wildlife Service seized more than $2m worth of ivory from two New York

City shops. Dan Stiles writes in Swara Magazine that New York and San Francisco

"appear to be gateway cities for illegal ivory import in the USA … China

is not the only culprit promoting elephant poaching through its illegal ivory

markets. The USA is right there with them."

Finally, we have the case of a Philadelphia-based ivory smuggler, Victor

Gordon, who

was arrested in connection with one of the largest US seizures of illegally

imported ivory in July 2011. More than one ton of elephant ivory was

seized. He pleaded guilty on 27 September 2012 and faces up to 20 years in

prison.

His lawyer, Daniel-Paul Alva, told the Wall Street Journal his client

has been co-operating with the investigation, and was "an innocent

dupe". He has already managed to postpone his sentencing for more than a

year. This would be unthinkable in Africa.

The war on poaching cannot be won

in the field unless we take on high-level corruption

Corruption

is what drives the vicious circle linking poverty to organised crime and is the

root cause of the current poaching crisis

In order to win the war against poaching we have to understand its causes. There are two main explanations for why poaching is endemic and so hard to eradicate in developing countries.

The first explanation is that poaching is driven by organised crime. A recent, widely publicised report by Born Free: “Ivory’s Curse: The Militarisation and Professionalisation of Poaching in Africa”, details the web of corruption linking crime cartels to government officials, army officers and businessmen.

In buying the services of the individuals they need to oil the wheels of their criminal enterprises, the cartels achieve a degree of high level cooperation between the public and private sectors that development agencies can only dream of.

Evidence of the inner workings of crime syndicates is, naturally, hard to come by. But there is plenty of evidence of the involvement of corrupt officials and police officers in the illegal wildlife trade, such as the recent arrest of two police officers in Kenya.

In its conclusions, the Born Free report in calls for anti-poaching investment to be strategically re-focused on the traffickers and cartels.

The second explanation is that poaching is driven by poverty. An earlier IUCN report on elephant poaching provides statistics showing that child mortality and other povert indicators are correlated to poaching intensity. The general conclusion is that poverty drives people to poach.

In this scenario poachers are victims of poverty, but they are also the actual killers of elephants and rhinos, and this is where most governments currently have to invest anti-poaching efforts. But in the longer-term the only sustainable solution is development, to alleviate the poverty that is the cause of poaching.

There is no reason to believe that these two very different explanations contradict one another. Both are almost certainly true. The trade in ivory and other illegal wildlife products is complex, diverse and constantly evolving, like any other trade. Like any other business enterprise, the crime cartels are constantly on the lookout for new opportunities to maximize their profits.

But: how are these two causes of poaching interconnected? In weighing up the evidence, we should bear the following points in mind:

(1) People are not criminals because they are poor. Africa is full of inspiring stories of community-based conservation and development initiatives: stories of poor people trying to make an honest living, using natural resources sustainably.

(2) You don't have to be poor to be a criminal. Rhino horns are regularly the target of thieves in the UK as well – here also there is evidence that the crime cartels are in the background, masterminding operations.

(3) Any high-value, lightweight product is going to attract the attention of organised crime cartels, be it drugs, diamonds or illegal wildlife products.

Note that it is value of the product that matters, not whether or not it is intrinsically "illegal". Cartels deal in prescription drugs as well as banned substances, in diamonds as well as rhino horns. This puts paid to arguments that legalising trade in rhino horn is the way to stop poaching.

Let’s look again at the conclusions of the IUCN report which shows a correlation between poaching and poverty. One of the first things that students of statistics are taught is that a correlation does not provide proof of causality. Poverty could be the cause of poaching, but the causal process could go in the other direction: could poaching could be the cause of poverty?

This might sound far-fetched, but poaching does contribute to poverty, by impoverishing communities of their natural capital which could be sustainably harvested or used through tourism for the benefit of wider society.

Poaching also introduces corruption and criminality into communities, leading to the incarceration of young working aged men. The insecurity brought by armed poachers threatens all investments – poachers are known to raid homes and markets for food, steal vehicles and even rape women.

The IUCN report finds that while areas where poverty is worst also see higher levels of elephant poaching, poor villagers do not benefit from the illicit ivory trade. Thus incomes for a few poachers are matched by threats to legitimate sources of income, driving the community greater into poverty and potentially into ever greater dependence on the poaching cartels.

I would argue that corruption what drives this vicious circle and is the root cause of the current poaching crisis. Corruption is the catalyst that binds poverty to organised crime and activates their full destructive potential.

Ingrained corruption in societies gives the cartels freedom of movement to exploit poor people and evade capture. Where corruption is already endemic, it is easy for criminals to further corrupt the system, taking advantage of existing networks developed, for example, for the drugs trade or human trafficking. Where there is no corruption, the cartels will take steps to introduce it.

Would a study of the statistics reveal a correlation between corruption and poaching in the MIKE countries? My guess is it would. Certainly there is evidence to support this hypothesis from one country, Botwana.

This country has long had a policy of zero tolerance for corruption. In the latest report issued by Transparency International, Botwana stands out on the map of Africa as having the continent’s lowest levels of corruption – lower than some European countries.

Botwana also has the largest population of elephants in Africa as well as the best record on poaching in Africa. In a desperate measure, Rhinos are now being moved to Botwana to put them beyond the reach of rampant poaching in neighbouring South Africa, where corruption is endemic at all levels of society.

But technology and manpower alone will not solve the problem so long as corruption is not dealt with. Anti-poaching investments in a country with good governance, like Botswana, will contribute towards effective surveillance and protection. But in corrupt countries, there is a real danger the money will end up funding the poachers instead.

In Kenya, there is chilling evidence of how sophisticated surveillance equipment like GPS locators, intended to protected rhinos, is being used by poachers, with the help of corrupt or frightened officials, to locate and target their prey.

The recent announcement of a substantial pay rise for Kenyan rangers protecting elephant and rhino sanctuaries is hugely welcome, a sign that the message that morale and commitment are as important as equipment is beginning to get through.

The corruption highlighted by Born Free Report is an insidious and largely unspoken and filthy threat, not only to African wildlife, but to society as a whole. But this threat is also an opportunity for environmentalists to achieve their long-held dream of mainstreaming the environment in national policy agendas.

To do so, local environmental activists must also become part of the mainstream, by uniting with other social forces in the broader struggle against corruption, and for a fair and just society where humans and animals alike are free to go about their legitimate business.

---

20 percent of Africa's elephants killed in three years – 'We ...

www.desdemonadespair.net/.../20-percent-of-africas-elephants-killed.ht...

Aug 21, 2014 - Desdemona

Despair is the clearinghouse for all of the very worst news ... to mostly to China, but also to

Thailand, the Philippines, Europe, and the U.S. ... that there are actually two, not one, species of elephant on the continent. ... by a Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species

program.

---

Boneyard: Three At-Risk Animal Species in Africa | Super ...

superscholar.org/africa/

While the two African rhino species are not on the IUCN Red List (the world's most

... The IUCN Red List vs the U.S. Endangered Species Act List ... the U.S. “is the second-largest destination market for illegally trafficked wildlife in the world.” .... elephant tusks are China and Thailand,

though they are not the only markets.

------------

THE LAWS OF IVORY The Truth

of Buying and Owning It

Published

by

January

17, 2014 . 83K Views . 69

Comments . 124

Votes

The biggest misconception that we hear or read about is that "all ivory is

ILLEGAL to own, buy or sell". If you believe this statement then I will be

selling a beautiful bridge, located in New York, on EBAY next week... no

reserve! In the next few paragraphs I have put together a simple summary of the

INTERNATIONAL and U.S.FISH & WILDLIFE laws which regulate the commerce of

ivory, which in turn is regulated by C.I.T.E.S. (Convention on the International

Trade in endangered Species) and the 'Marine Mammal Protection

Act'. C.I.T.E.S. is an organization that was formed in 1973 as a

multinational protege of the United Nations to meet every 2 years to review

data and set quotas to maintain levels of protection on species of both

plant and animal. Here's what they say on regulation of ivories:

AFRICAN ELEPHANT: This is on the C.I.T.E.S. endangered species list. The

importation, selling and buying of this ivory IS NOT ALLOWED INTERNATIONALLY.

It cannot be exported or imported to the U.S. and most of the countries

delegated to the U.N., BUT... it is LEGAL TO OWN, SELL, BUY, or SHIP within the

boundaries of the U.S. and there are NO PERMITS or REGISTRATION requirements!

*The majority of african elephant ivory is "old estate" ivory that

was brought into this country since its' inception.

ASIAN

ELEPHANT : Also on the C.I.T.E.S. Endangered species list and is

ILLEGAL to buy, trade, sell, import or export anywhere internationally or

INTERSTATE within the U.S.

MAMMOTH/MASTEDON:

These are two distinctively different animals for one thing but the ivory is

difficult to distinguish between the two. These mammals are extinct

and were on this earth 10 to 40,000 years ago so this ivory is COMPLETELY

UNRESTRICTED! Distinguishing the difference between Mammoth/Mastedon

ivory and Elephant ivory is determined by the angles where the cross grain

lines bisect each other. Angles greater than 120% indicate elephant

ivory and angles less than 90% indicate Mammoth/Mastedon ivory. Other

distinctions include the color of the inner layers of the ivory and the

outer layer referred to as the 'bark'.

HIPPO/WARTHOG:

These species are protected but not endangered. Because of over population and

a danger to humans, these animals are legally hunted by regulation for 'cull'

purposes. Permits and documentation are required for importing or

exporting this ivory but once it is in the U.S., NO PERMITS OR DOCUMENTS ARE

NECESSARY to buy or sell interstate.

SPERM

WHALE: An endangered species and regulated since 1973 by The Marine Mammal

Protection Act. NO IMPORTATION/EXPORTATION PERIOD! Interstate sales of

REGISTERED PRE-ACT teeth with SCRIMSHAW is allowed under a special Federal

Permit. Unregistered pre-act teeth can NO LONGER BE REGISTERED and CANNOT BE TRANSPORTED

across interstate lines for commercial purposes. THEY CAN BE SOLD 'INTRASTATE'

so long as STATE LAW does not prohibit it!

ANTIQUE

(100 YRS +) Scrimshaw Teeth can be sold Interstate.

BOWHEAD

WHALE: Protected Period! It is LEGAL TO SELL via an exemption allowing ESKIMOS

to hunt whales and then sell their crafts made from them.

WALRUS:

They have been regulated since 1972 under the Marine Mammal Protection Act and

reguated by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. The ivory that pre-dates the

12-21-1972 Law which bears the Alaska State walrus registration tags or

post-law ivory that HAS BEEN CARVED OR SCRIMSHAWED BY AN ALASKAN NATIVE

(Eskimo) is legal to buy , sell, and own. Any ivory that was/is obtained

after 12-21-1972 IS NOT LEGAL TO BUY OR SELL UNLESS" both

parties are Eskimo... BUT, it is LEGAL TO OWN. Permits are required(as to the

laws above) to export the ivory out of the U.S.

FOSSIL

WALRUS IVORY: No restictions. It is LEGAL TO BUY, SELL AND OWN anywhere in the

U.S. The exportation of this ivory DOES require a permit.

THE ABOVE

INCLUDES ANY AND ALL PARTS OF SUCH ANIMALS STATED

I AM A

MASTER SCRIMSHANDER AND HAVE BEEN DEALING IN SCRIMSHAW, ANTIQUES, COLLECTIBLES,

BOOKS AND RARE ITEMS FOR OVER 4 DECADES. I SELL REAL QUALITY ITEMS AND AM AN

"OLD SCHOOL" KIND OF GUY WHO BELIEVES IN HONEST AND OPEN TRANSACTIONS

COMMENTS;

In

1966-1967, I hunted elephants almost monthly in Gabon for the sole purpose of

providing meat to a large village whose men worked for a French forester. This

was the only protein the villagers ate on

a regular basis. The ivory was a secondary consideration, or none at all since I killed elephants with very small tusks of no value. Benjamin Tweedy is correct; the ban will only increase the rarity of ivory and thereby make it more valuable. CITES is an idiotic policy based on emotions, not facts and reality.

a regular basis. The ivory was a secondary consideration, or none at all since I killed elephants with very small tusks of no value. Benjamin Tweedy is correct; the ban will only increase the rarity of ivory and thereby make it more valuable. CITES is an idiotic policy based on emotions, not facts and reality.

Reply ·

What all

the more vitriolic anti-ivory folks here overlook is basic economics: Supply

DOES NOT create demand: rather, supply and demand meet to determine a price. If

all ivory is illegal, the price of ivory skyrockets, as the legal supply is

gone. At least in the short term, this would likely mean MORE illegal poaching.

There are other angles on this, of course: it would be, to a greater or lesser

degree, easier to detect illegal ivory, and maybe that would help

counterbalance the impact of shrinking supply. But don't imagine changing the

supply has any effect on the demand. Think prohibition, or the war on drugs.

Banning legal sources inevitably increases the amount from illegal sources

because of all the interesting things it does to the supply curve and where it

meets the demand curve.

Honestly, the best way to stop poaching would be to flood the market with some innocuous legal source of ivory: say a hog bred for large tusks as well as meat and hide. Then ivory would be so devalued that the risks and expenses associated with poaching and smuggling elephant tusks would become less and less worthwhile.

Honestly, the best way to stop poaching would be to flood the market with some innocuous legal source of ivory: say a hog bred for large tusks as well as meat and hide. Then ivory would be so devalued that the risks and expenses associated with poaching and smuggling elephant tusks would become less and less worthwhile.

Reply ·

I

inherited some elephant ivory and walrus ivory from my grandfather that is over

130 years old. How do I prove to eBay that it is legal so I can put it up for

auction?

Reply ·

· 3 · August 2 at 9:22pm

Franette Armstrong · Top Commenter · Redondo Union High School

While

some rationalize the market for old ivory by saying “the elephant died years

ago, so what’s the harm?” The truth is that any market for ivory creates a

demand for tusks, which is leading to the rapid extinction of elephants. In

fact, the more “valuable” ivory is seen as being, the more likely it is that

people who can’t afford antiques will buy new ivory as an investment. In

addition, it’s hard to tell the age of carved ivory, and new ivory can be

artificially aged and papers forged about when it was bought/sold, making

import and export exceptions for antique ivory a gigantic loophole that

international traders abuse to profit from their horrendous crimes. In February

2014 a partial ban on the import and export of elephant ivory was put in place

and is now in force, but sadly there are exceptions that permit antique,

noncommercial, and “personal use” import and export. Just as bad, it continues

to allow inhumane hunters to import elephant heads as trophies. The truth is,

ALL ivory came from a living, breathing elephant that had a better than yours,

more social intelligence, and should live as long as you do. Tusks cannot

removed without kiliing the elephant but rarely is the elephant dead when the

tusks are gouged out of its skull. For more info about tusks BEFORE you buy or

sell ivory, please go to: https://www.thedodo.com/community/Elegirl/the-truth-about-tusks-648225506.html

Reply ·

· 11 · July 31 at 4:43pm

Judi Reynolds · Top Commenter · Endicott College

I was just saying this exact thing yesterday to a

guy who stopped at my March for Elephants table yesterday! The only way to end

this nightmare is to totally devalue ivory with a total ban on the trade!

#NoIvory

Reply ·

· 5 · August 3 at 9:37am

Cheryl Pass ·

Top Commenter · Urbana University

Very

confusing. This article says it is legal to own, buy, sell, and ship ivory

within the U.S. I tried to list some old estate ivory sculptures on Ebay and

Ebay rejected the listings. So which is it? Can it be sold through normal Ebay

channels, or not? The ivory in question was brought back from Zaire by my

father-in-law in 1971. I have his passport information to show the dates. I

know there are collectors of this type of ivory, and since I have no interest

in keeping it, I'd like to sell it. If the above article is the rulebook for

Ebay, why can't I sell them?

Before the animal enthusiasts here jump all over me....one of the reasons I don't want to keep the ivory is because of the cruelty involved in harvesting it from Elephants. It makes me cringe just to look at it. I am in agreement that the killing of Elephants for ivory is an abomination. BUT....I have these pieces, the animals have been dead for over 40 years, and I had nothing to do with encouraging the practice.

So what do I do? I can't bring the animals back to life. I don't think selling something from 40 yrs. ago to a collector should be a problem. Help???

Before the animal enthusiasts here jump all over me....one of the reasons I don't want to keep the ivory is because of the cruelty involved in harvesting it from Elephants. It makes me cringe just to look at it. I am in agreement that the killing of Elephants for ivory is an abomination. BUT....I have these pieces, the animals have been dead for over 40 years, and I had nothing to do with encouraging the practice.

So what do I do? I can't bring the animals back to life. I don't think selling something from 40 yrs. ago to a collector should be a problem. Help???

Reply ·

· 1 · Edited · July 1 at 5:55pm

Cheryl -I'm with you. I also have an ivory elephant

tusk that I inherited, that I really don't want. Ebay took it down. If you find

another way to sell (get rid of) your ivory, please let me know. I'm thinking

there must be collectors of this stuff??

Reply ·

· 2 · July 21 at 3:43pm

Franette Armstrong · Top Commenter · Redondo Union High School

Michelle Foreman Freed

And how can Ebay tell from a seller's description whether the ivory is more than 100 years old? It can't. So anyone who buys ivory on Ebay is most likely contributing to the extinction of the African Elephant. At the rate we are going (96 elephants killed per day on average), elephants will be wiped off the face of this earth in 10-15 years. Is that acceptable to you? If not, do NOT buy or sell ivory!

And how can Ebay tell from a seller's description whether the ivory is more than 100 years old? It can't. So anyone who buys ivory on Ebay is most likely contributing to the extinction of the African Elephant. At the rate we are going (96 elephants killed per day on average), elephants will be wiped off the face of this earth in 10-15 years. Is that acceptable to you? If not, do NOT buy or sell ivory!

Reply ·

· 5 · July 31 at 4:46pm

Franette Armstrong · Top Commenter · Redondo Union High School

Michelle, if you are selling ivory you are

contributing to the extinction of elephants. At the rate they are being killed

by poachers (not counting normal deaths), elephants will be extinct in 10-15

years. Please educate yourself about what happens to an elephant before it dies

and its tusks are taken. You can start here...it's easy: https://www.thedodo.com/community/Elegirl/the-truth-about-tusks-648225506.html

Explore

More

----------

Unsustainable and illegal wildlife trade

Each year, hundreds of millions of plants and animals are caught or

harvested from the wild and then sold as food, pets, ornamental plants,

leather, tourist curios, and medicine. While a great deal of this trade is

legal and is not harming wild populations, a worryingly large proportion is

illegal — and threatens the survival of many endangered species. With overexploitation

being the second-largest direct threat to many species after habitat loss, WWF

addresses illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade as a priority issue.

JOIN THE

FRONTLINE!

Second-biggest

direct threat to species after habitat destruction

What

is wildlife trade?

Whenever people sell or exchange wild animal and

plant resources, this is wildlife trade. It can involve live animals and plants

or all kinds of wild animal and plant products. Wildlife trade is easiest to

track when it is from one country to another because it must be checked, and

often recorded, at Customs checkpoints.

Why

do people trade wildlife?

People trade wildlife for cash or exchange it for

other useful objects - for example, utensils in exchange for wild animal skins.

Driving the trade is the end-consumer who has a need or desire for wildlife

products, whether for food, construction or clothing.

For a more detailed list of the various uses of

wildlife, visit the TRAFFIC website.

What

is wildlife trade worth financially?

This is a difficult estimate to make. As a

guideline, TRAFFIC has calculated that wildlife products worth about 160 US

billion dollars were imported around the globe each year in the early 1990s. In

addition to this, there is a large and profitable illegal wildlife trade, but

because it is conducted covertly no-one can judge with any accuracy what this

may be worth.

What

is the scale of wildlife trade?

The trade involves hundreds of millions of wild

plants and animals from tens of thousands of species. To provide a glimpse of

the scale of wildlife trafficking, there are records of over 100 million tonnes

of fish, 1.5 million live birds and 440,000 tonnes of medicinal plants in trade

in just one year.

Why

is wildlife trade a problem?

Wildlife trade is by no means always a problem and

most wildlife trade is legal. However, it has the potential to be very

damaging. Populations of species on earth declined by an average 40% between

1970 and 2000 - and the second-biggest direct threat to species survival, after

habitat destruction, is wildlife trade.

Perhaps the most obvious problem associated with

wildlife trade is that it

can cause overexploitation to the point

where the survival of a species hangs in the balance. Historically, such

overexploitation has caused extinctions or severely threatened species and, as

human populations have expanded, demand for wildlife has only increased.

Recent overexploitation of wildlife for trade has

affected countless species. This has been well-publicized in the cases of

tigers, rhinoceroses, elephants and others, but many other species are affected.

This

overexploitation should concern us all...

§ ...because it harms human livelihoods.

Wildlife is vital to the lives of a high proportion of the world's population, often the poorest. Some rural households depend on local wild animals for their meat protein and on local trees for fuel, and both wild animals and plants provide components of traditional medicines used by the majority of people in the world. While many people in developed countries are cushioned from any effects caused by a reduced supply of a particular household item, many people in the developing world depend entirely on the continued availability of local wildlife resources.

Wildlife is vital to the lives of a high proportion of the world's population, often the poorest. Some rural households depend on local wild animals for their meat protein and on local trees for fuel, and both wild animals and plants provide components of traditional medicines used by the majority of people in the world. While many people in developed countries are cushioned from any effects caused by a reduced supply of a particular household item, many people in the developing world depend entirely on the continued availability of local wildlife resources.

§ ...because it harms the balance of nature.

In addition to the impact on human livelihoods caused by the over-harvesting of animals and plants is the harm caused by overexploitation of species to the living planet in a wider way. For example, overfishing does not only affect individual fishing communities and threaten certain fish species, but causes imbalances in the whole marine system. As human life depends on the existence of a functioning planet Earth, careful and thoughtful use of wildlife species and their habitats is required to avoid not only extinctions, but serious disturbances to the complex web of life.

In addition to the impact on human livelihoods caused by the over-harvesting of animals and plants is the harm caused by overexploitation of species to the living planet in a wider way. For example, overfishing does not only affect individual fishing communities and threaten certain fish species, but causes imbalances in the whole marine system. As human life depends on the existence of a functioning planet Earth, careful and thoughtful use of wildlife species and their habitats is required to avoid not only extinctions, but serious disturbances to the complex web of life.

Particular

problems are associated with illegal wildlife trade,

which is usually driven by a demand for rare, protected species which need to

be smuggled and/or by a desire to avoid paying duties. In illegal wildlife

trade, some species involved are highly endangered, conditions of transport for

live animals are likely to be worse and wildlife is more likely to have been

obtained in an environmentally damaging way. The existence of illegal trade is

also worrying because it undermines countries' efforts to protect their natural

resources.

Wildlife

trade can also cause indirect harm through:

§ Introducing invasive species which then prey on, or compete with, native

species. Invasive species are as big a threat to the balance of nature as the

direct overexploitation by humans of some species. Many invasive species have

been purposely introduced by wildlife traders; examples include the American

Mink, the Red-eared Terrapin and countless plant species.

Find out more about invasive species

Find out more about invasive species

§ Incidental killing of non-target species, such as dolphins and seabirds, when they are

caught in fishing gear. It is estimated that over a quarter of the global

marine fisheries catch is incidental, unwanted, and discarded. Incidental

killing of animals also happens on land when crude traps are set (for example,

for musk deer or duikers). These cause damage and death to a variety of animals

besides the intended ones.

Find out more about bycatch

Find out more about bycatch

Finally...while wildlife trade alone is a major threat to

some species, it is important to remember that its impact is frequently made

worse by habitat loss

and other pressures.

WWF's range of expertise ensures that the threats to the environment from wildlife trade are tackled from an informed and global standpoint.

WWF's range of expertise ensures that the threats to the environment from wildlife trade are tackled from an informed and global standpoint.

Captive

baby Sumatran Orang-utan (Pongo abelii).

© TRAFFIC SE Asia/Chris R. Shepherd

Download

The

skins of Indochinese tiger (Panthera tigris corbetti) and other rare cats are

openly displayed for sale in Cholon District, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

October 2002

© WWF-Canon / Adam OSWELL

Multimedia

- Video: Shops selling wildlife trade products

- Video: Grisly Wildlife Trade Exposed (National Geographic)

Earth

© NASA GSFC / F. Espenak

Are there particular trouble spots geographically?

There are certain places in the world where wildlife trade is particularly threatening or where targeted action would be particularly worthwhile.

These places are sometimes called 'wildlife trade hotspots' and include, for example, China's international borders and the eastern borders of the European Union. While these hotspots might be trouble areas at present, they also offer opportunities for great conservation success, if action and funds are well-focused.

There are certain places in the world where wildlife trade is particularly threatening or where targeted action would be particularly worthwhile.

These places are sometimes called 'wildlife trade hotspots' and include, for example, China's international borders and the eastern borders of the European Union. While these hotspots might be trouble areas at present, they also offer opportunities for great conservation success, if action and funds are well-focused.

The

ONCFS (National Office of Hunting and Wildlife) mobile brigade of intervention

is often called to record and deal with illegal trading in species. Guatemala

Amazon or Blue-crowned Amazon in a cage for transport. French Guiana.

© Roger Leguen / WWF-Canon

There are three

key areas where WWF and TRAFFIC work to address the threat of the illegal

wildlife trade.

Supporting the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

WWF provides technical and scientific advice to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). WWF and TRAFFIC carry out cutting-edge research on illegal wildlife trade routes, the effects of wildlife trade on particular species, and on deficiencies in wildlife trade laws — information which is essential for CITES members to keep abreast of new trends and react accordingly. This research is used to create new plans for dealing with the illegal widlife trade and also helps WWF and TRAFFIC promote the inclusion of new species in the CITES appendices or resolutions.

Tightening and enforcing legislation

It’s one thing to ban or limit trade in a particular species, but another to effectively enforce this — especially in developing countries where equipment, training, and funds for enforcement are often lacking. In addition, many countries still lack strict national legislation and/or appropriate penalties for illegal wildlife trade. To address this challenge, WWF helps countries comply with CITES regulations by helping to develop programmes, create regulations, runs workshops, assists enforcement efforts and funds anti-poaching brigades.

Public education

One of the most powerful tools of all for addressing illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade is to persuade consumers to make informed choices when buying wildlife-based products. This includes not just the people buying the end product, but also shop-keepers, suppliers, and manufacturers. WWF actively discourages the purchase of certain wildlife goods and encourages the production and purchase of sustainable wildlife goods such as those certified by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). WWF also works hand-in-hand with many communities around the world, providing practical help to overcome poverty and helping them use their local wildlife in a sustainable way.

Learn more about WWF's work to combat the trade in endangered species.

Supporting the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora

WWF provides technical and scientific advice to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). WWF and TRAFFIC carry out cutting-edge research on illegal wildlife trade routes, the effects of wildlife trade on particular species, and on deficiencies in wildlife trade laws — information which is essential for CITES members to keep abreast of new trends and react accordingly. This research is used to create new plans for dealing with the illegal widlife trade and also helps WWF and TRAFFIC promote the inclusion of new species in the CITES appendices or resolutions.

Tightening and enforcing legislation

It’s one thing to ban or limit trade in a particular species, but another to effectively enforce this — especially in developing countries where equipment, training, and funds for enforcement are often lacking. In addition, many countries still lack strict national legislation and/or appropriate penalties for illegal wildlife trade. To address this challenge, WWF helps countries comply with CITES regulations by helping to develop programmes, create regulations, runs workshops, assists enforcement efforts and funds anti-poaching brigades.

Public education

One of the most powerful tools of all for addressing illegal and unsustainable wildlife trade is to persuade consumers to make informed choices when buying wildlife-based products. This includes not just the people buying the end product, but also shop-keepers, suppliers, and manufacturers. WWF actively discourages the purchase of certain wildlife goods and encourages the production and purchase of sustainable wildlife goods such as those certified by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and Forest Stewardship Council (FSC). WWF also works hand-in-hand with many communities around the world, providing practical help to overcome poverty and helping them use their local wildlife in a sustainable way.

Learn more about WWF's work to combat the trade in endangered species.

Blood Ivory

Ivory Worship

Thousands of elephants die each year so that their tusks can be carved into religious objects. Can the slaughter be stopped?

By Bryan Christy

Photographs by Brent Stirton

IN JANUARY 2012 A HUNDRED RAIDERS ON HORSEBACK CHARGED OUT OF CHAD INTO

CAMEROON’S BOUBA NDJIDAH NATIONAL PARK, SLAUGHTERING HUNDREDS OF ELEPHANTS—entire

families—in one of the worst concentrated killings since a global ivory trade

ban was adopted in 1989. Carrying AK-47s and rocket-propelled grenades, they

dispatched the elephants with a military precision reminiscent of a 2006

butchering outside Chad’s Zakouma National Park. And then some stopped to pray

to Allah. Seen from the ground, each of the bloated elephant carcasses is a

monument to human greed. Elephant poaching levels are currently at their worst

in a decade, and seizures of illegal ivory are at their highest level in years.

From the air too the scattered bodies present a senseless crime scene—you can

see which animals fled, which mothers tried to protect their young, how one

terrified herd of 50 went down together, the latest of the tens of thousands of

elephants killed across Africa each year. Seen from higher still, from the

vantage of history, this killing field is not new at all. It is timeless, and

it is now.THE PHILIPPINES CONNECTION

In an overfilled church Monsignor Cristobal Garcia, one of the best known ivory collectors in the Philippines, leads an unusual rite honoring the nation’s most important religious icon, the Santo Niño de Cebu (Holy Child of Cebu). The ceremony, which he conducts annually on Cebu, is called the Hubo, from a Cebuano word meaning “to undress.”

Several altar boys work together to disrobe a small wooden

statue of Christ dressed as a king, a replica of an icon devotees believe

Ferdinand Magellan brought to the island in 1521. They remove its small crown,

red cape, and tiny boots, and strip off its surprisingly layered underwear.

Then the monsignor takes the icon, while altar boys conceal it with a little

white towel, and dunks it in several barrels of water, creating his church’s

holy water for the year, to be sold outside.

Garcia is a fleshy man with a lazy left eye and bad knees. In the mid-1980s,

according to a 2005 report in the Dallas Morning News and a related

lawsuit, Garcia, while serving as a priest at St. Dominic’s of Los Angeles,

California, sexually abused an altar boy in his early teens and was dismissed.

Back in the Philippines, he was promoted to monsignor and made chairman of

Cebu’s Archdiocesan Commission on Worship. That made him head of protocol for

the country’s largest Roman Catholic archdiocese, a flock of nearly four

million people in a country of 75 million Roman Catholics, the world’s third

largest Catholic population. Garcia is known beyond Cebu. Pope John Paul II

blessed his Santo Niño during Garcia’s visit to the pope’s summer residence,

Castel Gandolfo, in 1990. Recently Garcia helped direct the installation of

Cebu’s newest archbishop in a cathedral filled with Catholic leaders, including

400 priests and 70 bishops, among them the Vatican’s ambassador. Garcia is so

well known that to find his church, the Society of the Angels of Peace, I need

only roll down my window and ask, “Monsignor Cris?” to be pointed toward his

walled compound.Some Filipinos believe the Santo Niño de Cebu is Christ himself. Sixteenth-century Spaniards declared the icon to be miraculous and used it to convert the nation, making this single wooden statue, housed today behind bulletproof glass in Cebu’s Basilica Minore del Santo Niño, the root from which all Filipino Catholicism has grown. Earlier this year a local priest was asked to resign after allegedly advising his parishioners that the Santo Niño and images of the Virgin Mary and other saints were merely statues made of wood and cement.

“If you are not devoted to the Santo Niño, you are not a true Filipino,” says Father Vicente Lina, Jr. (Father Jay), director of the Diocesan Museum of Malolos. “Every Filipino has a Santo Niño, even those living under the bridge.”

Each January some two million faithful converge on Cebu to walk for hours in procession with the Santo Niño de Cebu. Most carry miniature Santo Niño icons made of fiberglass or wood. Many believe that what you invest in devotion to your own icon determines what blessings you will receive in return. For some, then, a fiberglass or wooden icon is not enough. For them, the material of choice is elephant ivory.

I press through the crowd during Garcia’s Mass, but instead of standing before him to receive Communion, I kneel.

“The body of Christ,” Garcia says.

“Amen,” I reply, and open my mouth.

After the service I tell Garcia I’m from National Geographic, and we set a date to talk about the Santo Niño. His anteroom is a mini-museum dominated by large, glass-encased religious figures whose heads and hands are made of ivory: There is an ivory Our Lady of the Rosary holding an ivory Jesus in one, a near-life-size ivory Mother of the Good Shepherd seated beside an ivory Jesus in another. Next to Garcia’s desk a solid ivory Christ hangs on a cross.

Filipinos generally display two types of ivory santos: either solid carvings or images whose heads and hands, sometimes life-size, are ivory, while the body is wood, providing a base for lavish capes and vestments. Garcia is the leader of a group of prominent Santo Niño collectors who display their icons during the Feast of the Santo Niño in some of Cebu’s best shopping malls and hotels. When they met to discuss formally incorporating their club, an attorney member cried out to the group, “You can pay me in ivory!”

I tell Garcia I want to buy an ivory Santo Niño in a sleeping position. “Like this,” I say, touching a finger to my lower lip. Garcia puts a finger to his lip too. “Dormido style,” he says approvingly.

My goal in meeting Garcia is to understand his country’s ivory trade and possibly get a lead on who was behind 5.4 tons of illegal ivory seized by customs agents in Manila in 2009, 7.7 tons seized there in 2005, and 6.1 tons bound for the Philippines seized by Taiwan in 2006. Assuming an average of 22 pounds of ivory per elephant, these seizures represent about 1,745 elephants. According to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), the treaty organization that sets international wildlife trade policy, the Philippines is merely a transit country for ivory headed to China. But CITES has limited resources. Until last year it employed just one enforcement officer to police more than 30,000 animal and plant species. Its assessment of the Philippines doesn’t square with what Jose Yuchongco, chief of the Philippine customs police, told a Manila newspaper not long after making a major seizure in 2009: “The Philippines is a favorite destination of these smuggled elephant tusks, maybe because Filipino Catholics are fond of images of saints that are made of ivory.” On Cebu the link between ivory and the church is so strong that the word for ivory, garing, has a second meaning: “religious statue.”

THE CATHOLIC-MUSLIM UNDERGROUND

“Ivory, ivory, ivory,” says the saleswoman at the Savelli Gallery on St. Peter’s Square in Vatican City. “You didn’t expect so much. I can see it in your face.” The Vatican has recently demonstrated a commitment to confronting transnational criminal problems, signing agreements on drug trafficking, terrorism, and organized crime. But it has not signed the CITES treaty and so is not subject to the ivory ban. If I buy an ivory crucifix, the saleswoman says, the shop will have it blessed by a Vatican priest and shipped to me.

Although the world has found substitutes for every one of ivory’s practical uses—billiard balls, piano keys, brush handles—its religious use is frozen in amber, and its role as a political symbol persists. Last year Lebanon’s President Michel Sleiman gave Pope Benedict XVI an ivory-and-gold thurible. In 2007 Philippine President Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo gave an ivory Santo Niño to Pope Benedict XVI. For Christmas in 1987 President Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan bought an ivory Madonna originally presented to them as a state gift by Pope John Paul II. All these gifts made international headlines. Even Kenya’s President Daniel arap Moi, father of the global ivory ban, once gave Pope John Paul II an elephant tusk. Moi would later make a bigger symbolic gesture, setting fire to 13 tons of Kenyan ivory, perhaps the most iconic act in conservation history.

Father Jay is curator of his archdiocese’s annual Santo Niño exhibition, which celebrates the best of his parishioners’ collections and fills a two-story building outside Manila. The more than 200 displays are drenched in so many fresh flowers and enveloped in such soft “Ave Maria” music that I’m reminded of a funeral as I look at the pale bodies dressed up like tiny kings. Ivory Santo Niños wear gold-plated crowns, jewels, and Swarovski crystal necklaces. Their eyes are hand-painted on glass imported from Germany. Their eyelashes are individual goat hairs. The gold thread in their capes is real, imported from India.

The elaborate displays are often owned by families of surprisingly modest means. Devotees have opened bankbooks in the names of their ivory icons. They name them in their wills. “I don’t call it extravagant,” Father Jay says. “I call it an offering to God.” He surveys the child images, some of which are decorated in lagang, silvery mother of pearl flowers carved from nautilus shells. “When it comes to Santo Niño devotion,” he says, “too much is not enough. As a priest, I’ve been praying, ‘If all of this stuff is plain stupid, then God, put a stop to this.’”

Father Jay points to a Santo Niño holding a dove. “Most of the old ivories are heirlooms,” he says. “The new ones are from Africa. They come in through the back door.” In other words, they’re smuggled. “It’s like straightening up a crooked line: You buy the ivory, which came from a hazy origin, and you turn it into a spiritual item. See?” he says, with a giggle. His voice lowers to a whisper. “Because it’s like buying a stolen item.”

People should buy new ivory icons, he says, to avoid swindlers who use tea or even Coca-Cola to stain ivory to look antique. “I just tell them to buy the new ones, so the history of an image would start in you.”

When I ask how new ivory gets to the Philippines, he tells me that Muslims from the southern island of Mindanao smuggle it in. Then, to signal a bribe, he puts two fingers into my shirt pocket. “To the coast guards, for example,” he says. “Imagine from Africa to Europe and to the Philippines. How long is that kind of trip by boat?” He puts his fingers in my pocket again. “And you just keep on paying so many people so that it will enter your country.”

It’s part of one’s sacrifice to the Santo Niño—smuggling elephant ivory as an act of devotion.

HOW TO SMUGGLE IVORY

I had no illusions of linking Monsignor Garcia to any illegal activity, but when I told him I wanted an ivory Santo Niño, the man surprised me. “You will have to smuggle it to get it into the U.S.”

“How?”

“Wrap it in old, stinky underwear and pour ketchup on it,” he said. “So it looks shitty with blood. This is how it is done.”

Garcia gave me the names of his favorite ivory carvers, all in Manila, along with advice on whom to go to for high volume, whose wife overcharges, who doesn’t meet deadlines. He gave me phone numbers and locations. If I wanted to smuggle an icon that was too large to hide in my suitcase, I might get a certificate from the National Museum of the Philippines declaring my image to be antique, or I could get a carver to issue a paper declaring it to be imitation or alter the carving date to before the ivory ban. Whatever I decided to commission, Garcia promised to bless it for me. “Unlike those animal-nut priests who will not bless ivory,” he said.

A few families control most of the ivory carving in Manila, moving like termites through massive quantities of tusks. Two of the main dealers are based in the city’s religious-supplies district, Tayuman. During my five trips to the Philippines I visited every one of the ivory shops Garcia recommended to me and more, inquiring about buying ivory. More than once I was asked if I was a priest. In almost every shop someone proposed a way I could smuggle ivory to the U.S. One offered to paint my ivory with removable brown watercolor to resemble wood; another to make identical hand-painted statuettes out of resin to camouflage my ivory baby Jesus. If I was caught, I was told to lie and say “resin” to U.S. Customs. During one visit a dealer said Monsignor Garcia had just called and suggested that since I’d mentioned that my family had a funeral business, I might take her new, 20-pound Santo Niño home by hiding it in the bottom of a casket. I said he must have been joking, but she didn’t think so.

Priests, balikbayans (Filipinos living overseas), and gay Filipino men are major customers, according to Manila’s most prominent ivory dealer. An antique dealer from New York City makes regular buying missions, as does a dealer from Mexico City, gathering up new ivory crucifixes, Madonnas, and baby Jesuses in bulk and smuggling them home in their luggage. Wherever there is a Filipino, I was often reminded, there is an altar to God.

And it seems Father Jay was right about a Muslim supply route. Several Manila dealers told me the primary suppliers are Filipino Muslims with connections to Africa. Malaysian Muslims figured into their network too. “Sometimes they bring it in bloody, and it smells bad,” one dealer told me, pinching her nose.

Today’s ivory trafficking follows ancient trade routes—accelerated by air travel, cell phones, and the Internet. Current photos I’d seen of ivory Coptic crosses on sale beside ivory Islamic prayer beads in Cairo’s market now made more sense. Suddenly, recent ivory seizures on Zanzibar, an Islamic island off the coast of Tanzania—for centuries a global hub for trafficking slaves and ivory—seemed especially ominous, a sign that large-scale ivory crime might never go away. At least one shipment had been headed for Malaysia, where several multi-ton seizures were made last year.

The Philippines’ ivory market is small compared with, say, China’s, but it is centuries old and staggeringly obvious. Collectors and dealers share photographs of their ivories on Flickr and Facebook. CITES, as administrator of the 1989 global ivory ban, is the world’s official organization standing between the slaughter of the 1980s—in which Africa is said to have lost half its elephants, more than 600,000 in just those ten years—and the extermination of the elephant. If CITES has overlooked the Philippines’ ivory trade, what else has it missed?

THE ELEPHANT MONK

The ivory carvers in Phayuha Khiri and Surin are the most famous in Thailand and the targets of most investigations there into the illegal ivory trade. Phayuha Khiri is so dedicated to ivory that in the town center, where one might expect to see a fountain, there’s a circle of four great white tusks. It takes me only minutes on the main street to realize I’ve seen this place before: Tayuman, Manila’s religious-supplies district; only here, instead of crucifixes and images of the holy family, are life-size images of famous monks, small images of the Buddha wrapped in plastic, and bracelets and other religious items bagged by the dozens. Vendor after vendor on both sides of this long street is a Buddhist wholesale outlet. The only people I see shopping during my visits to Phayuha Khiri are small knots of orange-robed monks.

I track down the village’s head ivory dealer—Mr. Thi, who’s wearing an amulet on an ivory necklace and an ivory belt buckle—tour his shops and carving operation, and also visit his McMansion-size home. Mr. Thi tells me that Phayuha Khiri’s carving industry was founded by a monk who liked to carve ivory amulets. Standing in his shop, I look over his shoulder and see a painting of Ganesh, the elephant-headed Hindu god, and beside him a Happy Buddha. Monks, I discover, give out amulets in return for donations. The better the donation, the better the amulet. Amulets blessed by certain monks are even more valuable.

The Elephant Monk, Kruba Dharmamuni, who used to be the Scorpion Monk and still displays a life-size statue of himself as a scorpion in his temple, wants to take me ivory shopping in Surin. Once upon a time Surin was home to the king of Siam’s royal elephant catchers, but today government-subsidized elephant keepers, mahouts, live a shadow of their old lives, dependent on their animals’ ability to kick a soccer ball or hold a paintbrush and create a “self-portrait” on an easel for tourists. Vendors selling ivory rings, bangles, and amulets line the entrance to Surin’s tourist park.

“Ivory removes bad spirits,” the Elephant Monk tells me. He wears the brown robes of a forest monk and chews steadily on betel-infused maak, which he spits out in great blood-like wads. He also wears ivory. Around his neck is an ivory elephant-head pendant suspended from ivory prayer beads representing the 108 human passions.

The elephant is a symbol of Thailand and is revered in Buddhism. According to legend, a six-tusked white elephant entered the right side of Queen Maya the night she became pregnant with Siddhartha Gautama. The Elephant Monk believes he was an elephant in a past life and is well-known among mahouts. He tells me he has 100,000 followers around the world, though during my visit to his temple only a few show up. They kneel before him with offerings and receive an amulet he has blessed.

Many Thais wear amulets, sometimes dozens, to bring them luck and protect them from harm and black magic. Bangkok’s amulet market is huge, with countless vendors selling tens of thousands of small talismans made of materials such as metal, compressed dust, bone—and ivory. High-end amulets can fetch $100,000 or more. There are magazines, trade shows, books, and websites devoted to amulet collecting. Amulets hang from the rearview mirror of almost every Thai cab. Ousted Thai leader Thaksin Shinawatra credits his Buddhist amulet with saving him in assassination attempts, and the Thai Army has distributed amulets to its border soldiers to ward off Cambodia’s black magic.

The Elephant Monk’s main income is from amulets, and he offers a strange variety, including images of himself and of the Buddha as well as amulets made with plastic-encased bits of bone from the skulls of dead pregnant women, pure corpse oil, soil from seven cemeteries, tiger fur, elephant skin, and carved ivory. Business is good enough that he’s building a new temple, Wat Suanpah, modeled in part after Thailand’s popular tiger parks—often front organizations, critics say, for the illegal tiger trade. The Elephant Monk suffered similar controversy when a recent television exposé reported that he’d starved an elephant to death for its skin and ivory, but he says it died of natural causes and he was only holding an elephant funeral. Besides, by shopping in Surin, he tells me, he can find all the elephant ivory and skin he needs. Before the exposé, he took in about one million baht ($32,000) a month from his gift shop, the Internet, and foreign travels. Now he’s down to about 300,000 baht a month. But, he says, in just three days in Malaysia or Singapore he could sell his followers one million bahts’ worth or more.