|

of Canada   1600 to 1699

1600 to 1699 Settlement, Fur Trade & War Introduction Beaver hats became the fashion rage in Europe in the early 17th century, and no self-respecting European was without one. This began a rush by both French and English merchants to establish control over the fur trade in the New World. Trading companies, including the Hudson's Bay Company (which still exists today) spang up almost overnight and many towns grew up around them. For the first time in history, hostilities between England and France washed over into the colonies. Land and ownership would change quickly and often, and the Native Peoples were caught in the middle.1600 - Fur Trade & the First 'Unofficial' Settlement --- Beaver hats became the fashion rage in Europe and the demand for beaver pelts increased enormously. One single pelt was valued more than a human life. --- François Grave du Pont (a.k.a. Pontgrave) and Pierre Chauvin de Tonnetuit sailed to Tadoussac and established the first unofficial settlement in Canada. Since they were Huguenot (French Protestant), the settlement was never officially recognized by the Catholic Church.

1602 - The Canada and Acadia Company --- Aymar de Clermont de Chaste was appointed Vice-Admiral of France by King Henri IV. He was commissioned to colonize New France and was granted a fur trade monopoly. To those ends, he created The Canada and Acadia Company. 1603 - Samuel de Champlain --- François Grave du Pont was appointed de Chaste's representative in New France. Samuel de Champlain sailed with him on his first voyage in March to New France. --- Samuel de Champlain's first voyage under the authority of The Canada and Acadia Company to set up fur trade and to enforce a fur trade monopoly.

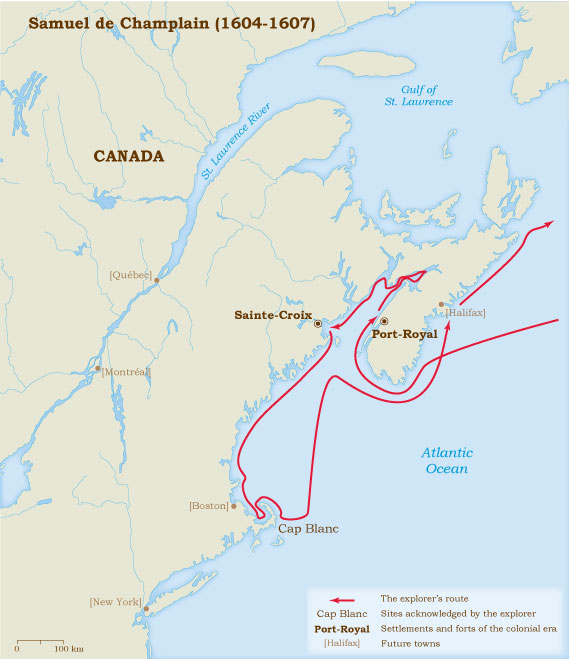

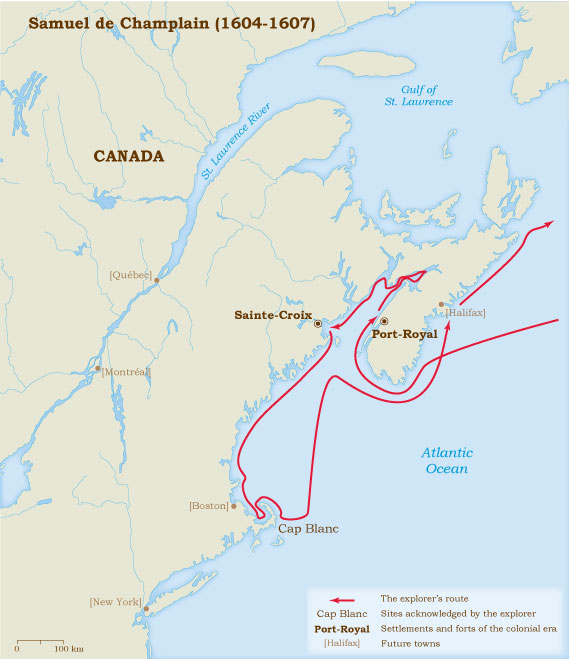

--- May 13 - Aymar de Clermont de Chaste died. Pierre du Gua de Monts replaced him as Lieutenant General of Acadia and took over the fur trade monopoly. --- May 27 - Champlain was told by the Montagnais and Algonkins that they had attacked an Iroquois village near the Iroquois River and massacred and scalped over 100 Iroquois. Champlain suspected exaggeration, but noted that it was an attempt by the Natives to show that they were seeking an alliance with the French. 1604 - Champlain and the Iroquois --- Champlain's second voyage. Champlain encountered the warring Iroquois near Cape Cod with disasterous results. He returned to the Bay of Fundy on the western shore of Nova Scotia.

1605 - Champlain - First Permanent Settlement in Canada --- Champlain founded Port-Royal (present-day Annapolis, Nova Scotia) which ultimately became the first permanent settlement in Canada. (see 'Champlain' Details, 1604) 1606 --- The Canada and Acadia Company went bankrupt. The de Monts Trading Company was formed by de Monts, Champlain, and Pontgrave. (see 'Champlain' Details, 1604) 1608 - Champlain - Québec & Conspiracy --- July 8 - Champlain founded Kebec (Québec - hereafter spelled 'Quebec'), the name deriving from the Algonkin word for 'where the river narrows'. Traitors, hired by the Spanish and Basque, conspired to murder Samuel de Champlain. Champlain discovered the conspiracy and his drastic actions ultimately sealed an alliance with the natives of Huronia.

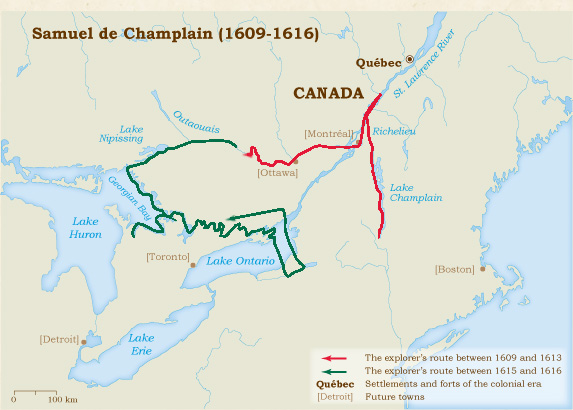

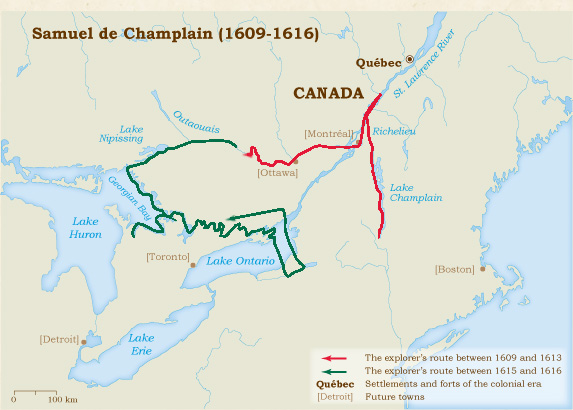

1609 - Champlain - Battle of Ticonderoga --- June 5 - A relief ship from France arrived in Quebec to find only 8 of the original 28 colonists left alive. The others had died of scurvy and winter. --- Étienne Brûlé was sent by Champlain to live among the Hurons as a 'truchement' ('embassador') (see 1610). Nicolas du Vignau was sent to live among the Algonquins on the Ottawa River. Savignon, son of the Algonquin chief Iroquet, was sent to live in France. The exchange was a great success. --- Champlain allied with the Natives north of the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River against the Iroquois to the south in the Battle of Ticonderoga. The battle would introduce European guns to the Iroquois with deadly results.

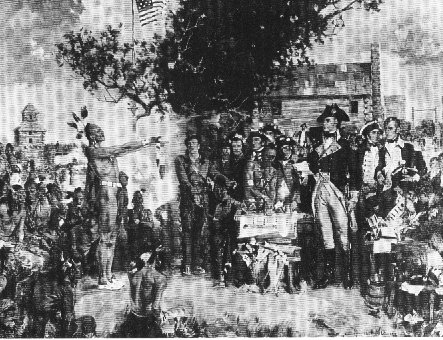

--- Arms trade following the Battle of Ticonderoga.

--- Writer Marc Lescarbot, who sojourned with Champlain, became the first historian of Canada with his book "A History of New France". --- Henry Hudson was commissioned by King James I of England to locate the Northwest Passage. (see 1610) --- The fur trade monopoly granted to The de Monts Trading Company was not renewed. The Company folded and de Monts formed a partnership with the Rouen Merchants. 1610 - John Guy - First English Settlement in Canada --- April 26 - The first Jesuits arrived in Quebec. They were not well-received in New France. Their ambiguous beliefs and anti-Christian actions were matters of great contention throughout their time in the New World.

--- May 2 - The Company of Adventurers and Planters of London and Bristol (a.k.a. The New Found Land Company) was established with the intent to colonize Newfoundland. --- John Guy and 39 colonists settled Cuper's Cove (present-day Cupid's Cove, Newfoundland) under King James I of England. Cuper's Cove became the first English settlement in Canada.

--- Étienne Brûlé became the first coureur de bois. His life among the Huron would lead him to adventure and, eventually, death.

--- Henry Hudson explored Hudson Bay, mistaking it for the Pacific Ocean, and became icebound in James Bay. (see 1611)

1611 - Henry Hudson - Mutiny --- The crew of the Discovery mutinied when Henry Hudson wanted to continue his search for the Northwest Passage. Hudson, his son, and 7 others were set adrift in Hudson Bay. No trace of them was ever found. (see 'Henry Hudson' Details, 1610) 1612 - John Guy and The Beothuk --- John Guy discovered the reclusive Beothuk, which would ultimately be the first and only recorded encounter with the Beothuk. (see 'John Guy' Details, 1611) 1613 --- With England's first settlement, Cuper's Cove (present-day Cupid's Cove), failing, John Guy resigned as Governor and returned to England. The settlement at Cuper's Cove was abandoned shortly thereafter. (see 'John Guy' Details, 1611) --- Samuel Argall, a pirate based in Virginia, attacked, looted and destroyed Port-Royal (present-day Annapolis, Nova Scotia). 1614 --- The Beothuk 'vanished' from the New World. (see also 1823)

1615 - Champlain and The Black Robes --- The name given to the missionaries by the Natives, there were 3 main groups of 'Black Robes': The Jesuits, the Récollets, and the Suplicians.

--- Three Récollet friars who were under directions from France and with orders to convert the Natives to Catholicism accompanied Champlain on his first journey into Huronia.

--- Champlain accompanied a Huron invasion party in an attack against the Iroquois. Champlain was wounded in battle.

--- Father Joseph le Caron celebrated the first mass in what is present-day Ontario. --- Schools were opened in Trois-Rivières and Tadoussac to teach Native children. More than teaching them, though, the French hoped to convert the children to Christianity. 1617 --- Louis Hébert became the first true permanent settler in Canada (one who supported his family from the land and not with supplies from the homeland).

--- Fort Trois-Rivières became a trading post. 1620 --- With France in civil war, King James I of England commissioned William Alexander to reclaim New France and Acadia under authority of John Cabot's claim in 1497.

--- Henri II, Duc de Montmorency, was named Viceroy of New France. Samuel de Champlain was appointed his lieutenant. De Montmorency began building Fort Saint Louis on the cliffs at Quebec. He formed the Compagne de Montmorency (Montmorency Company) and was granted an 11-year fur trade monopoly. --- June 3 - The cornerstone of the first stone church in Quebec, Notre Dame des Anges, was laid by the Récollets. --- The coureurs des bois (free fur traders) founded a trading post at Hochelaga (present-day Montreal) and named it Palace Royal. The coureurs des bois were considered pirates by the Church, so many of their accomplishments were attributed to either the priests or to other Frenchmen. 1621 --- King Louis XIII of France merged the Compagne de Montmorency and the Compagne des Marchands de Rouen et de Saint Malo. 1623 --- Henri II, Duc de Montmorency, established the feudal land system in Canada by granting the fief of Sault au Matelot to Louis Hébert, Canada's first permanent settler. (see 1617) 1624 --- The French established a peace treaty with the Wendat (Hurons), Algonkins (Algonquins) and the Iroquois. --- Armand-Jean de Plassis, Cardinal Richelieu, became Chief Minister to the French Crown and became the absolute master of New France. He imposed a monopoly on all commerce and proclaimed that all baptized (i.e. Catholic) colonists and Natives would receive equal rights. This action would create a caste system in Canada which would remain to present times. 1625 --- Henri II, Duc de Montmorency, resigned as Viceroy of New France. His nephew, Henri de Levis, Duc de Vantadour, took his place. Champlain remained as de Vantadour's lieutenant. 1626 - Jesuits --- Jesuit missionaries from the Society of Jesus began working amongst the Indians around Quebec to convert the Natives to Christianity. Jean de Brébeuf founded Jesuit missions in Huronia, near Georgian Bay.

--- The Iroquois destroyed the Mohicans and dominated all of eastern North America south of the St. Lawrence. They set their sights to the north. 1627 --- January 25 - Louis Hébert, Canada's first permanent settler, died after a serious fall on the ice. --- April 29 - The Company of One Hundred Associates (a.k.a. the Company of New France), organized by Armand-Jean de Plassis, Cardinal Richelieu, was given a fur-trade monopoly to all the lands claimed by New France. Champlain was named Lieutenant to the Viceroy of Canada and commissioned to establish a permanent colony of at least 4,000 people before 1643, which they failed to do. (see 1628)

--- Meanwhile, hostilities between England and France continued to grow. 1628 - The Kirke Brothers --- The French ships carrying colonists to Quebec were intercepted by the Kertk (Kirke) brothers, ultimately resulting in the surrender of Quebec. (see Details, 1627) 1629 --- July 19 - Louis Kirke attacked and took over Quebec in Britain's name. Champlain would work for the next 3 years to overturn the conquest of New France. (see Details, 1627) --- It is quite likely that the family of Louis Hébert (see 1617) swore allegiance to England in order to retain their property and belongings rather than to be deported as were many other French families following the fall of Quebec to the British. 1632 --- The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye returned Quebec to France under the condition that King Louis XIII pay the dowry of one million livres to England. Champlain returned to rebuild the colony. (see Details, 1627) 1634 --- Étienne Brûlé was murdered by the Hurons, either for trading with the Iroquois or for his sexual improprieties. The Hurons feared that Champlain would seek retribution, but Champlain, who now considered Brûlé a traitor, promised the Hurons that no action would be taken against them. 1634-1649 - Smallpox and the End of the Hurons --- With the coming of the 'White Man' came also White Man's diseases: Measles, Influenza, and Smallpox to name just a few. Thousands of Hurons died and, by 1649, the Iroquois had all but wiped out those who survived. Forty years after meeting Samuel de Champlain, the Huron Nation ceased to exist.

1635 --- December 25 - Samuel de Champlain died on Christmas Day in Quebec. 1637 --- Sir Louis Kirke (knighted in 1633) was made the first governor of Newfoundland. --- Jesuits founded the Jesuit College in Quebec. --- Jacques Marquette (of Marquette and Jolliet) was born in France. (see 1666) 1639 - Marie de l'Incarnation & the Ursuline Convent --- Marie de l'Incarnation embarked for New France, arriving on August 1. She became the first female missionary in Canada. Thanks to her frequent correspondence with her son, Claude, we have a unique glimpse into Canada's pioneer history. 1641 - Montréal --- Marie de l'Incarnation founded the Ursuline Convent in Quebec and became the first Mother Superior of New France. --- Catholic militants, The Mystics, founded Ville Marie (present-day Montréal, hereafter spelled 'Montreal'), led by Jérôme le Royer de la Dauversière and his wife, Paul de Chomedey de Maisonneuve (soldier and commander), and a nurse, Jeanne Mance (aged 34). Considered a 'foolhardy enterprise' by Governor Montmagny, the 'Society' was doomed to failure.

--- (circa 1641) Médard Chouart des Grosseilliers (of Radisson and Grosseilliers) arrived in New France. He spent several years in Huronia before meeting his future partner and brother-in-law, Pierre-Esprit Radisson. (see also 1651 and 1654)

1642-1667 - Iroquois Invasions --- For 25 years, New France was under almost constant siege by the Iroquois. Using guerrilla raids instead of outright invasions, the Iroquois brought fur trade to a complete standstill. Anyone venturing out of the safety of Montreal, Quebec, or Trois-Rivières, even to gather fire wood, did so at extreme risk. Smaller settlements were massacred. Dozens of Jesuit missionaries were brutally murdered and the missions destroyed. Many other missions were abandoned. The Iroquois destroyed what remained of the Huron Nation. These invasions ultimately resulted in a declaration of war by France against the Iroquois. 1642 --- Jesuit Isaac Joques, attempting to convert Iroquois to Christianity, was captured and tortured the first time. He returned in 1645, but on October 18, 1646, Joques was hacked to death by the Iroquois. He was only 39 years old. 1643 --- November 21 - René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle was born in Rouen, Normandy. He would come to be known as the Mad Explorer. Through trickery and some devious manipulations, la Salle would ultimately explore the Mississippi River and claim the entire Mississippi basin for France. (see 1667) 1645 --- Louis Jolliet (of Marquette and Jolliet) was born near Quebec in September. (see 1655) 1651 --- Pierre-Esprit Radisson (of Radisson and Grosseilliers) arrived in Trois-Rivières with his family. He was captured by the Iroquois with whom he lived for a time, escaped, and then made his way back to New France where he became partners with Médard Chouart des Grosseilliers. (see also circa 1641 and 1659)

1652 --- Iroquois defeated the Petun and Ottawa nations, gaining control of the entire St. Lawrence region. 1655 --- Louis Jolliet (of Marquette and Jolliet) was enrolled in the Jesuit college in Quebec at the age of 10 where he began his study for the priesthood. (see 1667) 1659 - Radisson and des Grosseilliers --- Following the loss of trade with the demise of the Huron Nation, the King of France commissioned Pierre-Esprit Radisson and his brother-in-law Médard Chouart des Grosseilliers to explore westward and set up trade relations with any natives they discovered. During their voyage, they discovered the headwaters of the 'Michissipi' River. The reactions to their return to Quebec would cause them to change allegiance to England (see 1665) and ultimately create the Hudson's Bay Company for England. (see 1669).

--- François de Laval arrived in Quebec as the Vicar General of the Pope in June. 1660 --- In May, about 500 Iroquois Natives attacked Long Sault. Defended by only about 60 people, including Adam Dollard des Ormeaux, Long Sault was able to withstand the attack. Because of this battle, tradition holds that the Iroquois were so impressed with the efforts of the small band of Frenchmen that they decided not to attack Montreal as originally planned. 1661 - King Louis XIV & War against the Iroquois --- The Prime Minister of France died and Pierre Boucher was sent from Trois-Rivières to France to beg help from 22-year-old King Louis XIV. Louis dreamed of ruling a huge empire and found Boucher's reports disturbing. He didn't want to begin his reign by losing New France to the Iroquois. King Louis XIV dismissed royal administration in the colony and appointed a governor and intendant and promised significant military support. War was declared on the Iroquois. 1662 - Alcohol --- February 23 - The first concerns over the trade of alcohol for furs were met with a decree which made the sale of alcohol to natives illegal under threat of excommunication. (see 1679) 1663-1673 - Filles de Roi (Daughters of the King) --- Over 800 Filles de Roi (Daughters of the King) were sent to New France for the purpose of settling there and marrying the many single male settlers. Unlike other women who had been brought to New Fance at the expense of the colonists, the Filles de Roi were sponsored by King Louis XIV of France.

1663 - Royal Province of Quebec --- Quebec became a royal province and Laval organized the Séminaire du Québec. (Originally a theological college, the Séminaire would eventually become the Université de Laval in 1852.) 1664-1671 - Engagés and Voyageurs --- Over 1,000 engagés (indentured servants) settled in New France, hired by colonial farmers, merchants, religious people, etc. Contracts lasted 3 years, during which time the engagés were denied citizenship, marriage, and were prohibited from becoming involved in fur trade. For their work, the engagés were paid 75 livres per year minus food, lodging and clothing. Their contracts could be bought or sold at any time without their consent. At the end of their tenure, the engagés had only the clothes on their backs, a few coins in their pockets, perhaps a gun if they were lucky enough, and their freedom. Most returned to France but many remained and became voyageurs, which were, essentially, canoeists for hire. 1664 --- Hans Bernhardt became the first recorded German immigrant. 1665 - Radisson & des Grosseilliers Change Allegiance --- Following the fines and confiscation of their furs in 1660, Radisson and des Grosseilliers secretly sailed to England where they switched their loyalties and began the process of forming the Hudson's Bay Company, a company which still exists in Canada. (see 1669)

--- Jean Talon became Quebec's first intendant (an administrative officer who oversaw agriculture, education, justice, trade, etc.). Talon arrived with the Carignan-Salières Regiment (1,200 soldiers who had been sent by King Louis XIV to deal with the Iroquois situation) and other representatives to the crown Governor Daniel de Remy de Courcelle, and the Commander of the troops, the Marquis of Tracy. (see 1666) 1666 - War without a War --- France launched its war against the Iroquois. Oddly enough, there would not be a single encounter, yet the war would end with a significant loss of life.

--- Jacques Marquette (of Marquette and Jolliet) arrived in New France. 1667 --- Canada's first census, counting 3,215 non-native inhabitants. --- Radisson and des Grosseilliers, having failed to secure a new commission from France, gained sponsorship from Prince Rupert, cousin of King Charles II of England. --- Louis Jolliet renounced his clerical vocation and left the Jesuit college at the age of 23 in order to become a coureur de bois. --- René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de la Salle, who had also renounced his Jesuit vows 2 years earlier, arrived in New France, his first step on the road to becoming The Mad Explorer. (see 1669)

1668 --- The Carignan-Salières Regiment was recalled to France. Several hundred, however, chose to remain in New France. --- Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette (of Marquette and Jolliet) arrived on assignment in Sault Ste. Marie where he met Louis Jolliet. Jolliet was well-aquainted with the Great Lakes region and could speak 5 indigenous native languages. (see 1673) 1669 --- Radisson and des Grosseilliers sailed to Hudson Bay on their first voyage under the British flag. This voyage would confirm the creation of the Hudson's Bay Company (see 1674). During the voyage, Radisson's ship became damaged in a storm and he was forced to return to England. Des Grosseilliers continued on the Nonsuch, returning later with a shipload of furs. He was richly rewarded and was dubbed Knight of the Garter by King Charles II.

--- La Salle's first voyage to the Mississippi River proved his incompetence as an explorer. (see 1673)

--- The Suplician missionaries of Montreal discovered that the Great Lakes were all linked on their first and only voyage into the Upper Country.

1670 - Hudson's Bay Company --- May 2 - The Hudson' Bay Company was founded by King Charles II. Underwritten by a group of English merchants, the royal charter granted trade rights over Rupert's Land to the company. (Rupert's Land included all the land draining into Hudson Bay. At its most powerful, the Hudson's Bay Company owned 10% of the entire land surface of the earth.) 1671 --- June 4 - Simon Daumont de Saint-Lusson formally took possession of the western interior of North America by declaration at Sault Ste. Marie. Effectively, the declaration claimed all the land from Sault Ste. Marie north to Hudson Bay, west to the Pacific Ocean, and south to the Gulf of Mexico. 1672 --- Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac became the Governor-General of New France. His first administration would last 10 years. Despite his haughtiness, Frontenac would accomplish much in New France before being recalled to France in 1682.

--- April 30 - Marie de l'Incarnation died in Quebec, never having returned to France and never having seen her son again. She was 72. --- Jesuit Father Charles Albanal travelled up the Saguenay River and reached Hudson and James Bays. 1673 --- Marquette and Jolliet were commissioned by Frontenac to explore the Michissipi (Mississippi) River to determine if it flowed into the Pacific Ocean (as hoped) or into the Gulf of Mexico (as feared).

--- La Salle constructed Fort Cataracoui (also Cataraqui, present-day Kingston, Ontario). In France, la Salle began his lifestyle as a shrewd con man in order to further his wealth and historical prominence. (see 1678)

1674 --- Radisson and des Grosseilliers renounced their allegiance to England and returned to France to explore and trade under the French flag.

--- Laval became the first Bishop of Quebec. 1675 --- Jesuit Father Jacques Marquette died at Green Bay from illnesses acquired during his trip down the Mississippi River. Louis Jolliet returned to Quebec where he was married. He became a renowned merchant who was often consulted by the colony officials when important trade and settlement decisions had to be made. (see also 1679)

1676 - End of the Coureurs des Bois --- April 15 - King Louis XIV signed a decree banning fur trade from private traders and trappers, the coureurs des bois. The decree forced the natives to travel to specific trading posts on specific days to trade their furs and the coureurs des bois eventually passed into history. 1678 Using bribery and deception, la Salle secured a commission from King Louis XIV to explore the Mississippi River. (see 1682)

--- Récollet priest Louis Hennepin became the first person to describe and to draw Niagara Falls. 1679 --- King Louis XIV signed another decree preventing the sale of alcohol outside any French dwelling and banned transportation of alcohol to any Native village under threat of severe penalty. --- Louis Jolliet was commissioned to travel to Hudson Bay in order to assess the expansion and success of the Hudson's Bay Company.

1681 --- Charles Aubert de la Chesnaye, friend to Pierre-Esprit Radisson, formed the Compagnie Française de la Baie d'Hudson (a.k.a the Northern Company) in an effort to compete with the Hudson's Bay Company of England. Radisson and des Grosseilliers were hired by the Company to reclaim the trading posts on Hudson Bay. This would ultimately be the final, tragic, and disturbing chapter in the Radisson and des Grosseilliers saga.

1682 - La Salle... the Mad Explorer --- April 9 - René-Robert Cavelier de la Salle reached the mouth of the Mississippi River after 4 years of exploring the length of the river. He claimed the entire Mississippi basin in the name of France and named it Louisiana after King Louis XIV. (see 1684)

--- King Louis XIV revolked the title of Governor-General granted to Louis de Buade, Compte de Frontenac in 1672 and recalled him to France. 1684 - La Salle and Louisiana Using altered maps, la Salle tricked the King of France into believing that Louisiana was rich in silver and that the mouth of the Mississippi River would be an ideal place for a colony and fort in order to stave off Spanish incursions from the south. The King named la Salle commander of all Louisiana and commissioned him to start a colony on the Mississippi Delta. La Salle's haughty, self-serving nature would ultimately result in his assassination. (see 1687)

1687 --- March 19 - La Salle was ambushed and shot in the head by Pierre Duhault. Mortally wounded, la Salle was stripped naked by his men. All his belongings were taken away and la Salle was left where he had fallen. 1689 - English Invasion --- May - France and England declared war. English colonists in New York heard the news first and convinced their Iroquois allies to attack the French. Most French colonies were unfortified. Their vast expansion had not allowed them to defend them properly. --- August 5 - 1,500 Iroquois attacked Lachine near Montreal, which became known as the Lachine Massacre. Of the 375 inhabitants, 24 were killed and 76 others were taken prisoner. Fifty-six of the 77 buildings were razed to the ground. --- October - Frontenac was renamed Governor of New France. He would come to be known as the Saviour of New France.

1690 - French Retaliation & King William's War --- Following the Lachine Massacre, Frontenac ordered a retaliatory attack on Albany in the British colony of New York. This war, the first in the British and French colonies, would come to be known as King William's War. --- February - Frontenac began his invasion. One hundred and sixteen militiamen and 96 Indian allies were placed in the charge of coureur de bois Nicolas D'Ailleboust de Manthet and brothers Jacques le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène (see October 16, 1690) and Pierre le Moyne d'Iberville (see 1696). They reached the fort at Schenectady and massacred 60 settlers. --- May 11 - Sir William Phips, (sent by Massachusetts) captured Port-Royal (Annapolis, NS). --- October 16 - Admiral Phips approached Quebec with 34 ships, including 4 warships. Phips sent Major Thomas Savage to demand the surrender of Quebec and the entire French colony. Frontenac's reply was: "The only answer I have for your general will come from the mouths of my cannon and muskets." Frontenac had been forewarned of the invasion and had secretly gathered 3,000 militiamen and natives. When Phips attempted a landing, he was surprised by resistance from Jacques le Moyne de Sainte-Hélène and the invasion was repulsed. le Moyne died in battle. --- October 24 - With many of his ships seriously damaged by artillery fire from Quebec, Phips weighed anchor and returned to Boston. 1694 --- Louis Jolliet was commissioned to explore and map the coastline of Labrador and to assess the trade possibilities there.

1696 - Les Canadiens & British Surrender --- France and England were at war yet again. Pierre le Moyne d'Iberville became the most famous 'Canadien', (colony-born soldier). He ejected the British from Hudson Bay and, in November, led 120 militia and Mi'kmaq warriors and attacked British fishing outposts on Newfoundland before attacking the settlement and fort at St. John's. In the attack on the settlement, d'Iberville had the homes torched, then scalped a prisoner named William Drew and sent the scalp into the fort with a demand for surrender. The British surrendered and abandoned St. John's to the French. --- For his efforts, d'Iberville was dubbed 'Chevalier de l'Ordre de Saint Louis', the highest military distinction in the kingdom of France. 1697 --- The Treaty of Ryswick assured that all lands captured during the struggles between the English and French were returned. 1698 --- November 28 - Louis de Buade, Comte de Frontenac died at Quebec. He was 76.

| ||||||||||||

http://www3.sympatico.ca/goweezer/canada/can1600.htm

http://www3.sympatico.ca/goweezer/canada/can1600.htm-----------------------

BLOGGED:

CANADA MILITARY NEWS; bits and pieces- Cool stuff that happens in Nova Scotia , Canada - everyday folk living in a world that works for us - getting by, living nature and loving what we have- rich folks need not apply- come visit and bring your aged and kids - u'll love it /some of that crazy no sheeeeeet sherlock Canada stuff if ur interested/NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC CANADA ROCKIES 1911

http://nova0000scotia.blogspot.ca/2015/08/canada-military-news-cool-stuff-that.html----------------------

O Canada- the new explorers

The Explorers

Samuel de Champlain 1604-1616

Samuel de Champlain (sometimes called Samuel Champlain in English documents) was born at Brouage, in the Saintonge province of Western France, about 1570. He wrote in 1613 that he acquired an interest “from a very young age in the art of navigation, along with a love of the high seas.” He was not yet twenty when he made his first voyage, to Spain and from there to the West Indies and South America. He visited Porto Rico (now Puerto Rico,) Mexico, Colombia, the Bermudas and Panama. Between 1603 and 1635, he made 12 stays in North America. He was an indefatigable explorer – and an assistant to other explorers – in the quest for an overland route across America to the Pacific, and onwards to the riches of the Orient.

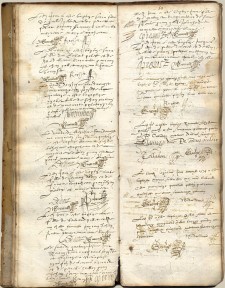

The name “Samuel,” taken from the Old Testament, suggests the possibility that Champlain was born into a Protestant family during a period when France was torn by endless conflicts over religion. However, by the time he undertook his voyages of discovery and exploration to Canada, he had definitely converted to Catholicism. The marriage contract between Samuel de Champlain and Hélène Boullé, dated 1610, shows that he was the son of the then-deceased sea captain, Anthoine de Champlain, and Marguerite Le Roy. On this basis, several historians have deduced that Champlain must have been born around 1570.

What are the chances of finding another baptismal certificate dating from this era where the names are identical to those we find in other historical documents? The chances are in fact very small indeed. However, even though the family names of Chapeleau and Champlain are similar, this small difference — understandable as it may be — cautions us not to jump to conclusions. Although the probability is slight, it is still possible that this document has nothing to do with our Samuel de Champlain.

If we are indeed looking at the baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, we can now say for certain that he was born into a Protestant family, most probably during the summer of 1574. But unless there is another discovery to equal the one made by Mr. Germe, a complete mystery will continue to surround Samuel de Champlain’s date and place of birth.

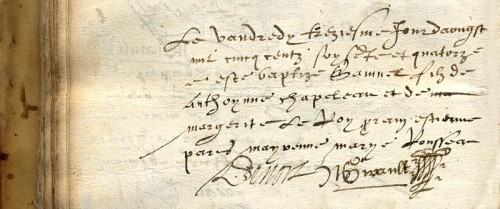

“On Friday, the thirteenth day of August, fifteen hundred and seventy-four, Samuel, son of Antoine Chapeleau and of m [word crossed out] Marguerite Le Roy, was baptized. Godfather, Étienne Paris; godmother, Marie Rousseau. Denors N. Girault.”

Thus Champlain sailed from Honfleur on the fifteenth of March, 1603, and prepared to follow the route that Jacques Cartier had opened up in 1535. He proceeded to explore part of the valley of the Saguenay river and was led to suspect the existence of Hudson Bay. He then sailed up the St. Lawrence as far as Hochelaga (the site of Montreal.) Nothing was to be seen of the Amerindian people and village which Cartier had visited, and Sault St. Louis (the Lachine Rapids) still seemed impassable. However, Champlain learned from his guides that above the rapids there were three great lakes (Erie, Huron and Ontario) to be explored.

While the settlers were tilling, building, hunting and fishing, Champlain carried on with his appointed task of investigating the coastline and looking for safe harbours.

The three years stay in Acadia allowed him plenty of time for exploration, description and map-making. He journeyed almost 1,500 kilometres along the Atlantic coast from Maine as far as southernmost Cape Cod.

The three years stay in Acadia allowed him plenty of time for exploration, description and map-making. He journeyed almost 1,500 kilometres along the Atlantic coast from Maine as far as southernmost Cape Cod.

Champlain also explored the Iroquois River (now called the Richelieu), which led him on the fourteenth of July, 1609, to the lake which would later bear his name. Like the traders who had preceded him, he sided with the Hurons, Algonquins and Montaignais against the Iroquois. This intervention in local politics was ultimately responsible for the warlike relations that were to pit the Iroquois against the French for generations.

Even more important, he succeeded in penetrating beyond the Lachine Rapids, becoming the first European (apart from Étienne Brûlé) to start exploring the St. Lawrence and its tributaries as a route towards the interior of the continent. Champlain was so convinced that it was the route to the Orient that in 1612 he obtained a commission to “search for a free passage by which to reach the country called China.” Like most of the explorers who followed after him, he could not carry out his mission without the support of the Amerindian population.

The following year Champlain was induced to make a voyage up the Ottawa River in the course of which he reached Allumette Island. It was his initial foray along the route that was to lead him to the heartland of present-day Ontario and eventually to reach Lake Huron on the first of August, 1615.

That was to be Champlain’s last voyage of exploration. In the years that followed, he devoted all his efforts to founding a French colony in the St. Lawrence valley. The keystone of his project was the settlement at Quebec.

That was to be Champlain’s last voyage of exploration. In the years that followed, he devoted all his efforts to founding a French colony in the St. Lawrence valley. The keystone of his project was the settlement at Quebec.

When it capitulated to the English Kirke brothers in 1629, Champlain returned to France, where he lobbied incessantly for the cause of New France. He finally returned to Canada on the twenty-second of May, 1633. At the time of his death at Quebec on the twenty-fifth of December, 1635, there were one hundred and fifty French men and women living in the colony.

The Mystery of Samuel de Champlain

In the title of his first book, published in 1604, Des Sauvages: ou voyage de Samuel Champlain, de Brouages, faite en la France nouvelle l’an 1603 [“Concerning the Primitives: Or Travels of Samuel Champlain of Brouages, Made in New France in the Year 1603”], Samuel de Champlain indicated that he was a native of Brouage in the Saintonge region of France. But a fire in the 17th century completely destroyed the town records of Brouage, where the young Champlain was believed to have spent his childhood. Since then, historians have speculated about the birth date of the man often described as the “Father of New France.”The name “Samuel,” taken from the Old Testament, suggests the possibility that Champlain was born into a Protestant family during a period when France was torn by endless conflicts over religion. However, by the time he undertook his voyages of discovery and exploration to Canada, he had definitely converted to Catholicism. The marriage contract between Samuel de Champlain and Hélène Boullé, dated 1610, shows that he was the son of the then-deceased sea captain, Anthoine de Champlain, and Marguerite Le Roy. On this basis, several historians have deduced that Champlain must have been born around 1570.

These are the few facts that history reveals, leaving room for all sorts of hypotheses about Champlain’s date of birth. But things were to take a different turn in the spring of 2012 when Jean-Marie Germe, a French genealogist, was examining the archives of the Protestant parish of Saint Yon de La Rochelle. In Champlain’s time, La Rochelle was a neighbouring town and rival of Brouage. What Mr. Germe found there was the baptismal record of Samuel Chapeleau, son of Antoine Chapeleau and Marguerite Le Roy, dated August 13, 1574.

Is this the baptismal certificate of the “Father of New France”? Certainly the document is difficult to read; the letters often have to be deciphered as much from their context, as from their appearance. Moreover, in that era the rules of spelling were flexible, to say the least. The different spellings used for the family name of the child and his father can be explained by the fact these names had perhaps previously been written down only rarely. A standard spelling had possibly not yet been adopted.What are the chances of finding another baptismal certificate dating from this era where the names are identical to those we find in other historical documents? The chances are in fact very small indeed. However, even though the family names of Chapeleau and Champlain are similar, this small difference — understandable as it may be — cautions us not to jump to conclusions. Although the probability is slight, it is still possible that this document has nothing to do with our Samuel de Champlain.

If we are indeed looking at the baptismal certificate of our Samuel de Champlain, we can now say for certain that he was born into a Protestant family, most probably during the summer of 1574. But unless there is another discovery to equal the one made by Mr. Germe, a complete mystery will continue to surround Samuel de Champlain’s date and place of birth.

“On Friday, the thirteenth day of August, fifteen hundred and seventy-four, Samuel, son of Antoine Chapeleau and of m [word crossed out] Marguerite Le Roy, was baptized. Godfather, Étienne Paris; godmother, Marie Rousseau. Denors N. Girault.”

In the Footsteps of Jacques Cartier

In 1602 or thereabouts, Henry IV of France appointed Champlain as hydrographer royal. Aymar de Chaste, governor of Dieppe in Northern France, had obtained a monopoly of the fur trade and set up a trading post at Tadoussac. He invited Champlain to join an expedition he was sending there. Champlain’s mission was clear; it was to explore the country called New France, examine its waterways and then choose a site for a large trading factory.Thus Champlain sailed from Honfleur on the fifteenth of March, 1603, and prepared to follow the route that Jacques Cartier had opened up in 1535. He proceeded to explore part of the valley of the Saguenay river and was led to suspect the existence of Hudson Bay. He then sailed up the St. Lawrence as far as Hochelaga (the site of Montreal.) Nothing was to be seen of the Amerindian people and village which Cartier had visited, and Sault St. Louis (the Lachine Rapids) still seemed impassable. However, Champlain learned from his guides that above the rapids there were three great lakes (Erie, Huron and Ontario) to be explored.

Acadia and the Atlantic Coast

After Aymar de Chaste died in France in 1603, Pierre Du Gua de Monts became lieutenant-general of Acadia. In exchange for a ten years exclusive trading patent, de Monts undertook to settle sixty homesteaders a year in that part of New France. From 1604 to 1607, the search went on for a suitable permanent site for them. It led to the establishment of a short-lived settlement at Port Royal (Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia.)While the settlers were tilling, building, hunting and fishing, Champlain carried on with his appointed task of investigating the coastline and looking for safe harbours.

Routes

From Quebec to Lake Champlain

In 1608, Champlain proposed a return to the valley of the St. Lawrence, specifically to Stadacona, which he called Quebec. In his opinion, nowhere else was so suitable for the fur trade and as a starting point from which to search for the elusive route to China. During this third voyage he learned of the existence of Lac Saint Jean (Lake St. John), and on the third of July, 1608, he founded what was to become Quebec City. He immediately set about building his Habitation (residence) there.Champlain also explored the Iroquois River (now called the Richelieu), which led him on the fourteenth of July, 1609, to the lake which would later bear his name. Like the traders who had preceded him, he sided with the Hurons, Algonquins and Montaignais against the Iroquois. This intervention in local politics was ultimately responsible for the warlike relations that were to pit the Iroquois against the French for generations.

From the Ottawa Valley to Lake Huron

In 1611, Champlain returned to the area of the Hochelaga islands. He found an ideal harbour, and facing it he built the Place Royale (royal square), around which the town would later develop from 1642 onwards.Even more important, he succeeded in penetrating beyond the Lachine Rapids, becoming the first European (apart from Étienne Brûlé) to start exploring the St. Lawrence and its tributaries as a route towards the interior of the continent. Champlain was so convinced that it was the route to the Orient that in 1612 he obtained a commission to “search for a free passage by which to reach the country called China.” Like most of the explorers who followed after him, he could not carry out his mission without the support of the Amerindian population.

The following year Champlain was induced to make a voyage up the Ottawa River in the course of which he reached Allumette Island. It was his initial foray along the route that was to lead him to the heartland of present-day Ontario and eventually to reach Lake Huron on the first of August, 1615.

Routes

When it capitulated to the English Kirke brothers in 1629, Champlain returned to France, where he lobbied incessantly for the cause of New France. He finally returned to Canada on the twenty-second of May, 1633. At the time of his death at Quebec on the twenty-fifth of December, 1635, there were one hundred and fifty French men and women living in the colony.

-----

The Changing Role of

Natives in the Exploration of Canada:

Cartier (1534) to Mackenzie (1793)

Conrad E.

Heidenreich

Introduction

After the French had built their first permanent

settlements on the east coast of Canada, Ste. Croix (1604), Port Royal (1605)

and Québec (1608), it took them only until 1681 to explore and roughly map the

shores of the Great Lakes and the Mississippi River to the Gulf of Mexico. This

was an astonishing achievement considering that the first Dutch and Englishmen

did not even see Lake Ontario until 1685. Conventional wisdom gives one to

understand that the French were strongly motivated to explore westward in order

to expand their fur trade, to proselytize the Natives and to seek a route across

the continent; and what enabled them to do so were the magnificent river systems

that connected the Great Lakes to the St. Lawrence River. By contrast, it is

said, these motives were all but absent among the Dutch and English as were the

easy routes leading westward.

Motives are of course only

an essential first step in defining goals; by themselves, without further

development, they remain a “pipedream.” To reach goals successfully involves

compromises and the development of appropriate cultural and technological

innovations necessary for the desired outcome. Penetrating westward into the

continent was a very real problem for Europeans who had to move through an alien

physical environment inhabited by people about whom they knew

nothing.

The key to European inland

exploration and fur trade expansion was learning how to cope with the physical

environment through which they had to travel and seeking the co-operation of the

Native populations who controlled that environment. By the end of the sixteenth

century, the French had discovered that the “magnificent” rivers that supposedly

led westward were in fact un-navigable to them; they were full of falls and

rapids, and flowed swiftly eastward from the Great Lakes to the St. Lawrence and

Atlantic coast making it difficult to travel westward, upstream. The St.

Lawrence River was a cul-de-sac. European transportation technology

(boats, horses, even walking) was useless under these conditions. Europeans who

wanted to use these rivers had to change the way they traveled before any

movement inland was possible. The canoe, which could have solved part of this

problem at an early date, was, until the early seventeenth century, an item of

Native technology that no European knew anything about. To Europeans, at first

glance, it was obviously “inferior” to their technology because it could not

carry the loads they were accustomed to take with them and required the skill to

paddle that only the Natives had. The canoe was in fact a technological

innovation that belonged to an alien culture, developed to overcome an alien

environment. Even if the canoe was recognized as a technological solution to a

transportation problem, knowledge of its construction and operation was still

required. This meant peaceful relations with the Native populations who

controlled not only the knowledge about canoes but also access to the lands in

the interior and how to live on those lands.

The expansion of the fur

trade into the interior of Canada was also a powerful motive to the French.

Since trade has to be mutually beneficial to both partners, it can only function

adequately under peaceful relations. The fur trade was a partnership to exploit

a resource that provided furs to one partner and durable utilitarian goods to

the other. But once trade was established there was still no reason why the

Natives should give the French access to their lands and those of their

neighbors. What could the French offer them in return? To the Natives, explorers

and to some degree traders, were men who wanted to travel across their lands

without a discernible purpose or with one that would contribute little to Native

concerns and in fact might jeopardize them. In order for explorers to be

permitted inland, the concerns of the Natives had to be understood and met in

some manner. This meant a diplomatic dialogue to see what each wanted from the

other. Such a dialogue was predicated on peaceful relations and a spirit of

co-operation.

Besides the motives of the

Natives, traders and explorers in promoting or hindering inland expansion, the

motives of the French government also have to be examined. While the support of

the French monarchs in finding a route across the North American landmass was

inconsistent, their policy regarding inland trading was at best ambivalent.

Until trading licenses (congés) were introduced in 1681, it was in fact

illegal for French traders to travel west of Montreal to the pays d’en

haut. This did not stop some men, like Radisson and Des Groseilliers who

began to carry out an illegal trade in the northwestern interior by the late

1650s, but if caught, they were subject to severe penalties. Such illegal

traders were called coureurs-de-bois. The fear of the home government was

that if the interior trade were permitted, too many men would leave the

fledgling colony, making it vulnerable to attack especially from the Iroquois.

They were also concerned that if French traders were to compete with Native

traders and trappers, animosities would be fomented that could jeopardize the

existence of the colony. By the early seventeenth century the French realized

that success in any of their enterprises in Canada depended on accommodating

Native concerns and demands. Whether it was safe settlement on the banks of the

St. Lawrence River, expansion of the fur trade, inland exploration, the

establishment of interior missions or protection of the colony from potential

Dutch-English aggression, the development of a Native policy based on trust and

friendship was essential. The problem was how to gain the trust that would lead

to peaceful co-operation.

What I would like to develop in the following pages is

a broad picture of the gradual evolution of French-Native relations that led to

the successful exploration of eastern Canada, and the adoption of French

methods, at a much later date, by English explorers traveling inland from Hudson

Bay. Without an understanding of these relations any explanation of the

exploration of Canada makes little sense.1 Lack of space precludes a discussion of

the reasons why the Dutch and English on the Atlantic coast did not develop a

comparable exploration program and instead had miserable relations with the

resident Native population.

The Sixteenth

Century

The sixteenth century began badly for the Canadian

Natives. In 1497 Cabot noted their presence but was too cautious to go inland

and seek them out.3 Four years later (1501) however, the first

Portuguese expedition under Gaspard Corte Real raided Newfoundland and captured

57 Beothuk who were sold into slavery in Lisbon.4 This was Canada’s first export commodity and thus

began a depressing litany of mutual distrust and hostility along the Atlantic

coast from the Arctic, south to Cape Cod and beyond. Kidnapped Native

individuals and small groups began to make appearances at European courts and

exhibitions.5 Friendly contact was rare and even when it

occurred often degenerated into fighting. Natives were regarded with suspicion.

They looked different from Europeans, their technology, social and political

institutions, if indeed they were acknowledged to exist, were deemed to be

obviously inferior, and worst of all, they were not Christians. That they might

be useful to Europeans in some way other than curios and slaves did not become

an issue until the early 1580s, except in one case, but only partially

so.

The partial exception was the expeditions of Jacques

Cartier. On his first expedition in 1534, after engaging in gift exchanges with

Mi’kmaq in Chaleur Bay, and with Stadaconans (the St. Lawrence Iroquoians) at

Gaspé, Cartier kidnapped two teen-aged boys (Dom Agaya and Taignoagny), sons of

the headman Donnacona.6 They were to learn French and serve as guides on a

return trip. The following year, they led Cartier’s ships to Stadacona where the

city of Québec is now located, but refused to be of further service, an act

Cartier regarded as treachery.7 This is the first instance in Canada of Natives

serving as guides for explorers. As Cartier’s men became increasingly unwelcome,

they were told stories about the wealthy “Kingdom of Saguenay,” stories that

were intended to draw them away from the Québec area (Canada, in

Cartier’s relations). These fables led Cartier to kidnap ten more Stadaconans,

including Donnacona and, yet again, his unfortunate sons in order that they

repeat their stories to the French court and serve as guides on a return

trip.8 By the time a new expedition was put

together in 1541, of the potential guides all but one little girl had

died.9 Eventually this expedition and one by

Roberval the following year led to fighting and closure of the St. Lawrence

River to Europeans.10

During the 1580s the French

continued to pursue their fisheries in the Gulf of St. Lawrence and began a

small trade in furs. Although the fisheries did not demand Native contact, some

contact did occur. With the fur trade however, contact became a necessity, and

that contact had to be friendly. By the beginning of the seventeenth century

therefore, French traders had developed seasonal trading contacts at various

places along the maritime coast and through the Gulf of St. Lawrence as far as

Tadoussac. Both sides understood each other in a rudimentary fashion and knew

from practice what goods the other wanted. The interdependence of trappers,

traders and manufacturers so characteristic of the fur trade had

begun.

The Seventeenth

Century

In 1602, two Montagnais men were invited from the

Tadoussac area to visit the French court of Henri IV. The following year they

were returned to present a proposal from the king to a huge gathering

(tabagie) of the Montagnais at Tadoussac; “that His Majesty wished them

well, and desired to people their country, and to make peace with their enemies

(who are the Iroquois) or send forces to vanquish them.”11 This proposal

was enthusiastically accepted, and with it the French had made an agreement, the

first of its kind, that permitted peaceful, unhindered French settlement on the

shores of the St. Lawrence River in return for helping the Montagnais against

the Iroquois. Samuel de Champlain, who was present at the tabagie, had to

deliver on that promise in 1609. After the tabagie, Champlain began his

resource survey along the St. Lawrence River, during which he developed the

beginnings of a plan to explore the Canadian interior. Before leaving Canada,

three months after he had arrived, he entered his ideas in the manuscript for

his first book, Des Sauvages (Paris, n.d. and 1604). His insights were:

i) that the Natives had useful geographical information that they were willing

to share; ii) that they would draw maps if asked; iii) that the only way to

travel in Canada was by canoe and by living off the land; iv) that the interior

could only be explored with Native help; and v) that the key to all of this was

friendly relations with those Natives among whom the French would settle and

those whose country they wanted to see.12

In 1608, Champlain returned to the St. Lawrence having

surveyed the Atlantic coast and having put some of his ideas about exploration

into practice. The following year, at the suggestion of the Montagnais he

broadened their alliance to include the Ottawa valley Algonquin and the Huron by

aiding them on a raid with two French volunteers against the Mohawk on Lake

Champlain.13 To gain greater trust with his “allies” he exchanged

young men in order that each would begin to learn the language and customs of

the other.14 Although he had been promised that he would be taken

to explore the interior, nothing happened. Impatient, he tried to buy canoes but

was not successful until four years later (1613). With two canoes, four men and

a Native paddler-guide, Champlain’s first solo exploring expedition lurched up

the Ottawa River. It soon became evident that steering a canoe was not easy for

the French neophyte paddlers. After a few days one Frenchman was sent back and

replaced by another Native who was hired to steer the second canoe. Eventually

the entire expedition returned prematurely because the Kichesipirini (Big River

People) Algonquin denied them further passage.15 To Champlain that meant further broadening the bonds

of friendship, which in turn meant supporting all the Natives with whom he was

in contact, as he had done in 1609 and 1610, in the one thing they wanted –

military aid against the Iroquois.16 At the first opportunity, which came in

1615, Champlain with ten men joined a Huron war party bent on destroying an

Iroquois village. Although Champlain considered the raid a military failure, it

cemented the new French-Montagnais-Algonquin-Huron alliance. That year also

marked the introduction of Recollet priests to the Huron.17

With the raid of 1615, the

French had gained access to the interior west of the Lachine rapids and had

proven themselves as allies. They did not organize trips or travel on their own,

but came as passengers in Native canoes hoping to be dropped off at appropriate

places. Some Frenchmen paddled and thereby gained confidence in handling a canoe

and the respect of their Native hosts. They also began to learn Native languages

and cultures. Trade was in Native hands, but the merchants sent

truchements (interpreter-trader’s agents) back with the various Native

traders to curry their favor as fur suppliers and customers for the following

season. These men were only incidentally explorers. Although we know the names

of about half a dozen, the only one about whom we know a little more was Étienne

Brûlé, who ranged widely but did not leave a personal record of where he had

been and what he saw.

With the permanent introduction of the Jesuits into

the missionary field in 1632, all those not under their control were recalled.

With that, the Jesuits also became explorers, diplomats and interpreters, roles

to which they were eminently suited through their training. They too traveled as

passengers. Only rarely did they strike out on their own, as they did in 1640-41

to the Neutrals near the west end of Lake Ontario.18 Like the Recollets before them in 1626-27,

they were lucky to get away with their lives because they went without

permission of the Huron. Europeans were tolerated but were not free to travel

where they wanted. The Jesuits made important discoveries through the

geographical reports of their Native hosts and travels of their donnés

(servants), some of who ranged more widely with the Natives than the

priests.19 By about 1648, the Jesuits were able to

put together the geography of all five Great Lakes for the first time in written

descriptions and maps.20

If we examine the first fifty years of French activity

we can see some interesting developments. The French were drawn westward in

order to find routes across the continent, to proselytize the Natives and to

persuade them to trap animals and bring the skins to the St. Lawrence merchants.

The key to these aims was friendly Native relations. Champlain learned that he

had to aid the Natives in war in order to gain their trust; without them

exploration was impossible. The priests were tolerated because, initially at

least, they were regarded as being innocuous and were portrayed by the French as

important men and symbols of friendship between them and their Native allies. In

expanding their interior missions to seek more Native converts the priests aided

the cause of exploration. Although Pope Paul III had declared the Natives to be

human on 29 May 1537, under the Encyclical Sublimus Dei,21 many Europeans remained doubtful and regarded them at

best as uncultured savages. Through their missions and publications the Jesuits

in particular helped to transform this image. The Jesuit de Brébeuf, for

example, argued that the Natives should be seen “as ransomed by the blood of the

son of God, and as our brethren,”22 while the lawyer Marc Lescarbot argued that “they

share your human nature” and “to call them savage is unmerited and

abusive.”23 Among the French the question of intellectual or

racial inferiority did not arise. Some aspects of Native culture were abhorred,

especially their belief systems, and every effort was made to change these.

Familiarity did not “breed contempt,” but over time a great deal of

understanding. To the Jesuits, the Native was “perfectible” in a Christian sense

if he converted and gave up certain customs that conflicted with

Christianity.24 In 1635, in order to hasten the spread of

Christianity, the Jesuit Superior at Québec, Father Paul Le Jeune proposed to

the governor, Champlain that they try to promote Huron-French

intermarriage.25 Champlain agreed not only for religious

reasons, but also because intermarriage was a

way of further cementing French-Native alliances. He also thought that by

building a settlement in the Huron country, the French/Huron population could

complete the exploration of the continent.26 While the Huron were ambivalent about accepting this

proposal, the French court accepted and still promoted it during the late 1660s,

namely that French and Natives “mingle” and “constitute only one people and one

race.”27 The civil, mercantile and religious authorities saw

the Natives as human beings with whom they could live, travel, go to war,

explore and intermarry. Acceptance of each other as human beings was a first

step in opening the country to exploration. A second step was that the French be

willing to learn from the Natives how to cope in the Canadian environment. This

meant relinquishing aspects of their culture when they were away from the

colony, such as food, clothing, shelter, etiquette and modes of transportation.

By the time of Champlain’s death (1635), Natives and French were beginning to

adapt to each other, and the French to Canada’s natural environment. These

adaptations eventually led to the remarkably peaceful exploration of

Canada.

In 1648, the Iroquois wars turned more virulent and

with the Iroquois victories the interior missions, the fur trade, the system of

Native alliances and any hope of further exploration collapsed. In 1653 the

Onondaga offered to make peace on behalf of all Iroquois except the Mohawk, an

offer the French eagerly seized. Father Simon Le Moyne was chosen to go to

Onondaga and work out the details. This led to the opening of the mission Ste.

Marie de Gannentaa and the exploration of the Iroquois country.28 The following year Des Groseilliers and a

companion were asked by Governor Lauson to accompany a group of

Huron-Tionnontati traders who were returning to the western Great Lakes where

they had fled from the Iroquois.29 They had taken advantage of the impending peace to

trade at the St. Lawrence settlements. The aim of Des Groseilliers’ journey was

to contact as many Native groups as possible in the hope of reviving the fur

trade. Although this was not an exploring expedition, it resulted in significant

oral reports, especially to the Jesuits who were keenly interested in opening

missions to the refugees from the east who had settled around the western Great

Lakes. With these reports and others gathered from the Montagnais, Cree and

Algonquin, Father Druillettes managed to put together a good perspective on the

geography north of the St. Lawrence and Great Lakes.30 Parts of his map survived in Tabula

Novae Franciae – 1660, which was published in François Du Creux’s

Historiae Canadensis (Paris,

1664). A renewed outbreak of war with the Iroquois in 1658 collapsed inland

exploration again. It convinced the French that peaceful trade, the missions and

exploration could only be gained through a major war against the Iroquois. In

1659, while the colony was debating the dwindling prospects of reviving their

activities in the pays d’en haut unless an army was sent from France, Des

Groseilliers, this time with Radisson, joined a small group of Ojibwa on the way

to their refuge on the south shore of Lake Superior. The governor however,

fearing that many men needed to protect the colony would follow them to seek

their fortune, had forbidden Radisson and Des Groseilliers to go. Consequently

Des Groseilliers was briefly incarcerated upon their return the following

year.31 They did however bring news to the Jesuits

of the location of large Native populations, most of them refugees from the

Iroquois wars, in the Green Bay area and along the south shore of Lake Superior.

A few weeks after the return of the two traders, Father Druillettes met a

Nipissing convert, Michel Awatanik, who had paddled from Green Bay with his

family to James Bay and from there via the Rupert River and Lake Mistassini to

Tadoussac between 1658 and 1660.32 Des Groseilliers’ and Awatanik’s

geographical reports made the Jesuits determined to launch a missionary effort

north toward James Bay and west to Lake Superior. Father Ménard headed west in

1660, and the following year Fathers Dablon and Druillettes, accompanied by

three traders and guided by Awatanik and his family, went north from Tadoussac.

Ménard lost his life trying to find a dying convert in the forest against the

advice of his Native hosts. The other party had to return half way to James Bay

when Awatanik became totally distraught and incapable of guiding after he lost

his family to convulsive seizures.33 French exploration was still entirely

dependent on Native support.

In 1665, a substantial army of 1200 soldiers arrived

in Canada and forced a peace on the Iroquois.

With them came Jean Talon the new Intendant. One of his first acts was to

develop an exploration policy.34 Although French traders were at the time

not permitted to go west of Montreal, the search for minerals, souls and staking

of land claims against the English was encouraged. With the Iroquois at peace

and with the confidence the French had developed in traveling and living outside

the colony, expeditions again left for the interior. These were organized far

differently from earlier ones. No longer were the French merely passengers. They

paddled their own canoes and hunted along the way, but still carried Native

guides and interpreters, particularly when they entered unknown areas. Also in

the interior were a growing number of coureurs de bois, illegal traders

who lived, traveled and traded with the Natives much to the annoyance of the

authorities. This period saw the explorations of La Salle, Peré, the Jolliet

brothers Louis and Adrien, Daumont de Saint-Lusson, Fathers Albanel, Allouez,

Hennepin, Marquette, and many others. One example will suffice to show how

dependent the French still were on Native support.35

When the two Sulpicians,

Dollier and Galinée, left Montreal in July 1669, to establish a mission to the

Shawnee on the Ohio River, they had a Shawnee guide with whom they could barely

communicate because his Algonquin was very different from that which the priests

had learned in the Montreal area. Knowing that they would encounter Iroquois,

they needed a second interpreter. Although their companion La Salle claimed to

speak Iroquoian, the two Sulpicians did not believe him (correctly as they

discovered) and hired a Dutchman who could speak Iroquois but unfortunately

little French. By the time they were portaging from Lake Ontario to the Grand

River both their guide-interpreters had disappeared. Luckily they met Adrien

Jolliet on the portage who was on his way to Montreal. He gave them a map and

told them of a canoe he had hidden on the shore of Lake Erie. The Sulpicians

spent a pleasant winter beside a little river on the north shore of the lake,

but the following spring on the day after they set out, one of their canoes blew

away in a storm with some of their baggage. A few days later they lost most of

their remaining supplies in a night storm. They had left their packs on the

beach, too tired after paddling all day to move them to high ground. Now their

plans to establish a mission had to be abandoned. Fortunately they found

Jolliet’s canoe and eventually made their way to the Jesuit mission at Sault

Sainte-Marie. None of these mistakes would have occurred if Native guides had

been with them.

A well-organized trip that set a new standard was

Marquette and Jolliet’s exploration of the Mississippi in 1673.36 During the winter Jolliet had collected

Native maps and geographical accounts, enabling him to have had a good idea

where he was going and what he would find before he set out. Both Jolliet and

Marquette spoke enough Native languages to take them through the known areas as

far as the Fox River where they hired their first guides. From there they

proceeded cautiously south, promoted good relations with the Natives they met

and hired interpreters as they needed them. This was one of the first journeys

of exploration that the French made with less Native

help.

La Salle’s explorations were the first done

substantially without Native help, but were hampered by a lack of good Native

relations, especially with the Iroquois (1680) and the Santee Dakota (1681).

Some of his men, Accault, Auguel and Hennepin, did however equip themselves with

Native maps before setting off for the Mississippi in 1681, and collected

geographical information from the Santee while in their captivity.37

After 1681, when the interior trade was legalized

through a permit (congé) system, French canoe traffic and establishment

of posts increased markedly.38 So did the capacity of the canoes on which

the entire interior trade and exploration was dependent. Because trading

licenses were in canoe loads, enterprising canoe builders at Trois- Rivières and

Montreal gradually transformed the standard 15-23 foot Native canoe into the

much larger voyageur canoe up to twice the original length, eventually with

capacities of over four tons. Along the edge of the explored Great Lakes

employees of the traders began to contact Native groups who lived further north

and west by traveling either with them or by hiring guides to take them there.

Some of the best known are, Daniel Greysolon de Dulhut in the Lake Superior area

and headwaters of the Mississippi (1683-84); Jean Peré from the north shore of

Lake Superior to James Bay (1684); and Jacques de Noyon westward from Lake

Superior to Rainy Lake (1688).

In the mid-1680s, war broke out again with the

Iroquois. Exploration was curtailed as men were channeled into the militia and

fur trading was intensified to pay for the war. In 1685, Dutch-English merchants

from Albany tried to use the confusion of the war to send trading expeditions to

the eastern Great Lakes (Roseboom and MacGregory). This is the first mention

that any English from the eastern colonies had made it to any of the Great

Lakes. They were guided not by Natives but by renegade Frenchmen. French militia

and traders apprehended them in 1687 and deported them.39

By 1697, the war was effectively over, but trading, helped by the capture

of the H.B.Co. posts in 1686 had been so successful that a huge glut of beaver

had developed on the markets in Paris (some 1 mill. livre weight or ca.

500, 000 skins).40 Consequently most of the interior trading

posts were closed and exploration halted except out from the New Orleans

colony.

The Eighteenth

Century

a) The French

After the Treaty of Utrecht (1713) and the

disappearance of the glut in beaver (due to moths and vermin), the French began

to re-open their interior posts. By the mid-1720s they were ready to continue de

Noyon’s explorations west of Lake Superior to discover the much-rumored La

Mer de l’Ouest.41 Information about the “western sea” came from the

Cree and Assiniboine, as did the maps gathered by La Vérendrye senior to take

them there.42 Equipped with guides and maps the various members of

the La Vérendrye family, ably assisted by their nephew La Jemerais, began to

push westward in slow stages by canoe and in constant contact with the resident

Native groups. Their 1738 journey from the Assiniboine River to the Missouri was

on foot as they traveled with a village of Assiniboine on their way to visit the

Mandan. Other villages were contacted as they moved along and presents given to

smooth the way. In 1741, two of La Vérendrye’s sons, Louis-Joseph and François,

with Native guides, struck out across the plains on horses to within sight of

the Big Horn Mountains. Although the French had long wanted to probe westward

along the Saskatchewan River, constant wars between members of the Blackfoot

confederacy and the Assiniboine-Cree alliance prevented them from doing so.

Several French attempts to promote peace came to nothing. Finally in 1751 the

opportunity came when it seemed a peace had been worked out with the Blackfoot.

Two canoes with ten men were sent westward with some Blackfoot prisoners the

French had ransomed from their Cree-Assiniboine allies who were to be returned

as peace offerings. A post was built within sight of the Rocky Mountains.

Unfortunately, a troop of Assiniboine warriors, who had followed the French,

came upon a Blackfoot village near the new French post and massacred its

occupants, thus ending further exploration. 43

Although the push westward was the main thrust of

French exploration in the eighteenth century, there was some other activity,

most notably the geographical inquiries and maps gathered from Montagnais

informants by the Jesuit Father Pierre Laure during the early 1730s. These maps

were used by Nicolas Bellin and became the standard maps of the northern

interior of Quebec until the surveys made in the nineteenth century.44

b) The English

English exploration outward from the shores of Hudson

Bay began in the same way as earlier French exploration. The first was by Henry

Kelsey, a young man of 23 years, who volunteered to head inland with Assiniboine

traders who were returning to their camps on the edge of the plains in

1690.45 He was the first European to see the Canadian west.

Two years later he returned. Unfortunately he wrote his journal in “poetry”

making it difficult to know where he had been. The next was William Stewart who

was sent to make peace in 1715 between the Cree and Chipewyan in order that the

latter could come unhindered to Fort Churchill to trade. He was the first

European traveler into the northern “Barren Grounds” (tundra). It is certain

that Stewart would never have returned if it had not been for the diplomacy and

linguistic skills of Thanadelthur, a Chipewyan woman who had been a slave among

the Cree, but was ransomed by the H.B.Co. to be Stewart’s guide.46

These were the only journeys out from the “bayside”

until 1754, when the H.B.Co. decided to send men inland to winter and to meet

French competition. These men were the so-called “winterers.”47 They would leave from York Factory with Cree and

Assiniboine traders, travel up the Hayes or Nelson Rivers in the late summer and

return the following spring, always traveling as guests of various Natives

groups. Anthony Henday, in 1754, was the first of these. Others followed every

year until 1774 when the H.B.Co. built Cumberland House, their first interior

post. The next significant probe into the northern “Barren Grounds” after

Stewart was by Samuel Hearne.48 He was given a number of tasks, of which finding the

Coppermine River with its supposed copper deposits and the possibility of an

east-west passage across the north were the most important. He set out on foot

in November 1769, after the muskeg had frozen, with Cree and Chipewyan guides. A

month later he was back in Churchill, his guides having deserted him for lack of

food. A second attempt early in 1770 also came to naught. In the late fall of

the same year he met the experienced Chipewyan headman Matonabbee who offered to

guide him. In Matonabbee’s opinion, Hearne’s previous expeditions ended in

failure because his incompetent guides had not taken enough women along to carry

the baggage, pitch the tents and cook while the unencumbered men procured food.

Matonabbee’s insight is worth quoting because, in a somewhat politically

incorrect manner by present standards, it conveys what it took to explore the

“Barren Grounds” successfully.

“For, said he, when all the

men are heavy laden, they can neither hunt nor travel to any considerable

distance; and in case they meet with success in hunting, who is to carry the

produce of their labor? Women were made for labor; one of them can carry, or

haul, as much as two men can do. They also pitch our tents, make and mend our

clothing, keep us warm at night; and, in fact, there is no such thing as

traveling any considerable distance, or for any length of time, in this country,

without their assistance. Women though they do every thing, are maintained at a

trifling expense; for as they always stand cook[ing], the very licking of their

fingers in scarce times, is sufficient for their

subsistence.”49

The expedition departed on

7 December 1770 and returned, 30 June 1772, after completing a vast sweep

through the tundra and edge of the boreal forest. Without Matonabbee and his

family of seven wives and retinue to guide and take care of him, Hearne could

not have succeeded in this journey.

After the mid-1770s, the fur trade increasingly drove

exploration. Competition between the H.B.Co. and the newly created North West

Co. made it necessary to find Native groups in fur-producing areas that would

undertake trapping. In 1778, Peter Pond of the Nor’westers “discovered” the 20

km-long Methy Portage (Portage la Loche), the only practical link to the

Athabaska country from the headwaters of the Churchill River and other rivers

already explored north of the upper Saskatchewan. The Cree and the Chipewyan who

wanted a trading post in the Athabaska area to save them the dangerous trip to

the “bayside” posts, had shown Pond this route. The Methy portage opened the

fur-rich Athabaska country to traders. As Peter Pond became more familiar with

the southern edge of the Athabaska area, he speculated that the Slave River that

connected Lake Athabaska to Great Slave Lake might have its outlet at the

Pacific Ocean. If it did, this would be a much shorter route for exporting furs

than the overland trip to the St. Lawrence River.50 The person who decided to explore this route was one

of Pond’s partners in the N.W.Co, Alexander Mackenzie.51 Mackenzie did not need guides since he was exploring

a river, but he needed hunters who would provision him and act as interpreters