Over 100 Black Canadians served in the Royal Canadian Air

Force WWII Their Stories

Recruits

of quality

Related Links

News Article / February 16, 2016

By Major Mathias Joost

February is Black History Month. Canadians take this

time to celebrate the many achievements and contributions of black Canadians

who, throughout history, have done so much to make Canada the culturally

diverse, compassionate and prosperous nation it is today. During Black History

Month, Canadians can gain insight into the experiences of black Canadians and

their vital role in the community.

The Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) has always

attempted to select the best possible candidates from among Canadian society.

In the period prior to the Second World War there was much competition to gain

one of the few positions in the air force. The RCAF could afford to choose the

best candidates. The need for manpower during the war did not reduce the

quality of the recruits being accepted. In 1940, the RCAF had an agreement with

the Army that the RCAF could talk to the best Army volunteers and see if they

wished to join the air force. Post-war, the RCAF continued to select only the

best.

This selection of the best of Canada’s young men and

women can be seen in the achievements of black Canadians who served in the air

force. Michael Manley served as aircrew in the RCAF and in 1972 became the

fourth prime minister of Jamaica. Lincoln Alexander, Leonard Braithwaite and Lloyd

Perry all became lawyers, with Alexander becoming the first black member of

Parliament and the first black lieutentant-governor of a Canadian province.

Leonard Braithwaite became the first black member of the provincial parliament

in Ontario, being responsible for pushing through important anti-discrimination

policies while Lloyd Perry became a director in the Ontario attorney general’s

office, responsible for protecting the rights of children.

Some black-Canadians remained in the RCAF after the

war and went on to distinguished careers. Sammy Estwick enlisted in December

1941, serving until 1963. He worked in telecommunications in the RCAF, both as

an instructor and as an operator, continuing in this field after he retired. In

his retirement he helped found the Ottawa Lions Track and Field Club and the

Gloucester Senior Adults’ Centre as well as serving as president of both. He

also served in leadership positions with the Vanier Lions Club and the Society

for Technical Communication.

Eric Watts went from being an airman to a squadron

leader when he retired. Wherever he went he was considered to be one of the

best, whether serving as an instructor or as a section head. As the wing air

armaments officer at 1 Wing in Marville, France, he took the wing’s armaments

serviceability rate from last to first among the four wings in the Canadian Air

Division.

The post-war RCAF also had its share of quality

recruits. Among the many who distinguished themselves were George Borden and

Wally Peters. George Borden served from 1953 to 1985. He then served five years

as executive assistant to the province’s Ministry of Social Services, being the

first black in Nova Scotia in this position and was the province’s first

literacy coordinator for blacks from 1988 to 1991. He is also a well-known poet

and songwriter.

Wally Peters enlisted as a fighter pilot, going on to

become a Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) advisor to the UN on the tactical movement

of troops by air and the CAF’s first human rights officer. On retiring he went

on to work with Transport Canada, helping create aviation safety programs and

helping establish the Canadian Aviation Safety Board. He might be best known

however, for having served as a member of the Snowbirds.

Black-Canadians have always been ready to serve Canada.

The RCAF has benefitted from the quality of those who have served, as has

Canada and its people. The foregoing are just some of the examples of their

excellence.

E.V. Watts profile

When Eric Victor Watts enlisted in the RCAF on

May 10, 1939, technically, he should not have been allowed to join. The federal

Cabinet and the RCAF had approved enlistment policies earlier that year that

stated recruits had to be of “pure European descent”.

Eric Watts was black.

However, the recruiting officer in Calgary, Alberta,

likely saw the potential in Watts and allowed him to become a member of the

RCAF. The recruiter’s decision certainly seems prescient.

From the very start, Watts proved himself to be a

natural leader. He enlisted as an armourer and served at several units and

schools. He was identified as being a superior instructor and supervisor who

rose rapidly to the rank of warrant officer class 2.

Throughout the war, the RCAF sought out members who

wished to become aircrew. In December 1943, Watts began the selection process

to become a pilot, for which he qualified in March 1945. He remained in Canada

and served as a pilot at several schools until November 1946. As the RCAF had a

surplus of pilots in the period of the interim air force of 1945-47, he went

back to being an armaments instructor and supervisor of armaments sections.

His leadership skills shown through and was

continually recommended for commissioning from the ranks. Finally, in February

1951, a place was available and he was commissioned as a flying officer while

on the RCAF ground defence course.

As an officer, he was as an instructor as well as a

supervisor of armaments sections at Trenton and Camp Borden, both in Ontario.

In November 1955, Watts was posted to RCAF headquarters in Ottawa, Ontario, where

he worked on armaments programs, including the development of the Sparrow II

missile that was planned for the Avro Arrow.

In August 1959, Watts was finally able to get the

posting he wanted. He was posted to Marville, France, as the maintenance armaments

officer at 445 Squadron and eventually became the wing armaments officer at 1

Wing in Marville. He took an organization that was ranked last in terms of

serviceability of aircraft armaments systems and made it the best of the four

RCAF wings in Europe. As a result of his outstanding work he was promoted to

squadron leader on January 1, 1962. He returned to Canada in July 1963

and served in both leadership and staff positions until he retired in 1966.

The fact that there was a black senior non-commissioned

officer supervising or instructing during the Second World War, one who was

consistently highly rated, speaks to Watts’ leadership ability.

At a time when racism was still quite prevalent in

Canadian society, he was continually rated as an outstanding instructor and

supervisor. Throughout this service he was always considered superior, usually

graduating at or near the top in his courses. Wherever he served, he held the

respect of both his subordinates and his fellow officers, being regarded as an

affable and highly capable individual. Considered an outstanding officer, it

was only his lack of a university education that hindered his progression to

higher rank.

Eric Watts passed away in Belleville, Ontario, on

March 18, 1993.

NEGRO SPIRITUALS- Pearleen Oliver

NOVA SCOTIA SENIORS IN SONG- 1983

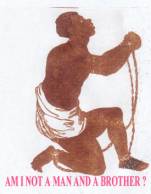

A number of familiar Negro Spirituals are included in this

song book. These spirituals originated,

over a period of 250 years, in the minds and souls of an enslaved people.

Brought from Africa to America as slaves, between the years

1619 and 1860, these victims of man’s inhumanity to man give birth to thousands

of spontaneous songs. The range from extremem sorrow (Nobody know De

Trouble I see) to songs of hope and happy expectations (Goin’ to shout all over

God’s Heab’n)

They were never written;

They were sung in dialect and unaccompanied.

The words and melody might change from day to day and

sometimes would convey hidden meaning, such as the Escape Song “Steal Away,

Steal Away, I Ain’t Got Long to Stay Here”.

These Spirituals are sung today in African Baptist Churches

of Nova Scotia and at all cultural gatherings.

NOVA SCOTIA SENIORS IN SONG- L’Age d’or chante, Sinnesearan A’Seinn

,Kisiku Ketapekiet

New Horizons/Nouveaux Horizons CANADA DAY 1983

--------------

Goin' Shout All Over God's Heaven (Negro Spiritual)

----------------

Thomas Dorsey- If You See My Savior

-----------------

Swing Low, Sweet Chariot By Etta James

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Thz1zDAytzU

-------------------------

Good News Bible- John: 15: 18-27

- THE WORLD’S HATE

------------------------

#KNAAN- #TREVOR NOAH TDS- Ethiopia needs us in 2016 and Africas- millions starving dying- Let's organize a fundraiser.... and have it youth driven and make sure it gets to the actual people... because in this world... #allblacklivesmatter

Young Artists For Haiti - Wavin' Flag

---------------------------------------------------------

America's music was born in Nashville when the Fisk Jubilee Singers brought to worldwide recognition the Christian spirituals of American slavery. After the Civil War, Northern missionaries, answering the Lord's call to go south and teach the freedmen, found there a long-suffering people with a deep and great faith in the same Lord and Savior, Jesus. This gospel reunion produced Fisk University and the Jubilee Singers and ultimately America's music.

------------------------

1967

OUR

LORD AND SAVIOUR- JESUS CHRIST

This

is so uplifting....IRNI - THAT'S MY KING-...Jesus Christ of Nazareth-

King of The Jews- Israel- Land of our Bible- Land of the Scriptures

....YOU

CAN'T OUTLIVE HIM.....AND YOU CAN'T LIVE WITHOUT HIM...... Oh Praise the

Lord... Our Lord and Saviour...Jesus Christ

Dr.

S.M. Lockeridge -That's My King: Do you know him? -

1976 sermon in Detroit

TRUST-

in His timing

RELY-

on His promises

WAIT-

for His answers

BELIEVE-

in His miracles

REJOICE-

in His goodness

PRAY-

for His blessings

REST-

in His Love

COMMENT:

We

need this kind of preaching today. No

beating around the bush or worrying about offending anyone. Tell them like it is,just as Jesus did.

------------------

Mark Twain on his porch "It is utterly beautiful to me; and it moves me infinitely more than any other music can. ... in the Jubilees and their songs, American has produced the perfectest flower of the ages."

---------------

The story of the negro spirituals is closely linked to the History of African Americans, with its three milestones:

1865: the abolition of slavery

1925:the Black Renaissance

1985: the first Dr Martin Luther King’s Day.

Before 1865

Almost all the first Africans who arrived in the New World were slaves. They came from several regions of the African West Coast.

Almost all the first Africans who arrived in the New World were slaves. They came from several regions of the African West Coast. Their ways of living were described by slaves themselves, in some narratives. They had to work either in plantations or in town.

Slavery was an important issue facing Churches, as slaves were allowed to meet for Christian services. Some Christian ministers, such as J. D. Long, wrote against slavery.

Rural slaves used to stay after the regular worship services, in churches or in plantation “praise houses”, for singing and dancing. But, slaveholders did not allow dancing and playing drums, as usual in Africa. They also had meetings at secret places (“camp meetings”, “bush meetings”), because they needed to meet one another and share their joys, pains and hopes. In rural meetings, thousands slaves were gathered and listened to itinerant preachers, and sang spirituals, for hours. In the late 1700s, they sang the precursors of spirituals, which were called “corn ditties”.

So, in rural areas, spirituals were sung, mainly outside of churches. In cities, about 1850, the Protestant City-Revival Movement created a new song genre, which was popular; for revival meetings organized by this movement, temporary tents were erected in stadiums, where the attendants could sing.

So, in rural areas, spirituals were sung, mainly outside of churches. In cities, about 1850, the Protestant City-Revival Movement created a new song genre, which was popular; for revival meetings organized by this movement, temporary tents were erected in stadiums, where the attendants could sing. At church, hymns and psalms were sung during services. Some of them were transformed into songs of a typical African American form: they are "Dr Watts”.

The lyrics of negro spirituals were tightly linked with the lives of their authors: slaves. While work songs dealt only with their daily life, spirituals were inspired by the message of Jesus Christ and his Good News (Gospel) of the Bible, “You can be saved”. They are different from hymns and psalms, because they were a way of sharing the hard condition of being a slave.

Many slaves in town and in plantations tried to run to a “free country”, that they called “my home” or “Sweet Canaan, the Promised Land”. This country was on the Northern side of Ohio River, that they called “Jordan”. Some negro spirituals refer to the Underground Railroad, an organization for helping slaves to run away.

NEGRO SPIRITUALS AND WORK SONGSDuring slavery and afterwards, workers were allowed to sing songs during their working time. This was the case when they had to coordinate their efforts for hauling a fallen tree or any heavy load. For example, prisoners used to sing "chain gang" songs, when they worked on the road or some construction. But some "drivers" also allowed slaves to sing "quiet" songs, if they were not apparently against slaveholders. Such songs could be sung either by only one or by several slaves. They were used for expressing personal feeling, and for cheering one another. |

NEGRO SPIRITUALS AND THE UNDERGROUND RAILROADThe Underground Railroad (UGRR) helped slaves to run to free a country. A fugitive could use several ways. First, they had to walk at night, using hand lights and moonlight. When needed, they walked (“waded”) in water, so that dogs could not smell their tracks. Second, they jumped into chariot, where they could hide and ride away. These chariots stopped at some “stations”, but this word could mean any place where slaves had to go for being taken in charge.So, negro spirituals like “Wade in the Water”, “The Gospel Train” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” directly refer to the UGRR. |

Between 1865 and 1925

Slavery was abolished in 1865. Then, some African Americans were allowed to go to school and be graduated. At Fisk University, one of the first universities for African American, in Nashville (Tennessee), some educators decided to raise funds for supporting their institution. So, some educators and students made tours in the New World and in Europe, and sang negro spirituals (Fisk Jubilee Singers). Other Black universities had also singers of negro spirituals: Tuskegee Institute, etc.Just after 1865, most of African Americans did not want to remember the songs they sung in hard days of slavery. It means that even when ordinary people sang negro spirituals, they were not proud to do so.

In the 1890s, Holiness and Sanctified churches appeared, of which was the Church of God in Christ. In these churches, the influence of African traditions was in evidence. These churches were heirs to shouts, hand clapping, foot-stomping and jubilee songs, like it was in plantation “praise houses”.

At the same time, some composers arranged negro spirituals in a new way, which was similar to the European classical music. Some artists, mainly choruses, went abroad (in Europe and Africa) and sang negro spirituals. At the same time, ministers like Charles A. Tindley, in Philadelphia, and their churches sang exciting church songs that they copyrighted.

Between 1925 and 1985

In the 1920s, the Black Renaissance was an artist movement concerning poetry and music. “It was an evidence of a renewed race-spirit that consciously and proudly sets itself apart”, explained Alan Locke. So, the use of dialect was taboo, in this movement. The “race-spirit” infused the work of musicians and writers like Langston Hughes. For the first time, African Americans realized that their roots were deep in the land of their birth. The Black Renaissance had some influence on the way of singing and interpreting negro spirituals. First, the historical meaning of these songs were put forward. Then, singers were pushed to be more educated.For example, in early Twentieth century, boys used to sing negro spirituals in schoolyards. Their way of singing was not sophisticated. But educators thought that negro spirituals are musical pieces, which must be interpreted as such. New groups were formed, such as the Highway QC’s (QC : Quincy College), and sung harmonized negro spirituals

This constant improvement of negro spirituals gave birth to another type of Christian songs. Thesewere inspired by the Bible (mainly the Gospel) and related to the daily life. Thomas A. Dorsey was the first who composed such new songs. He called them Gospel songs, but some people say “Dorseys”. He is considered as being the Father of Gospel music.

It is of interest to see that, during this period, African Americans began to leave the South and went North. Then, Gospel songs were more and more popular in Northern towns, like Chicago.

Between 1915 and 1925, many African American singers, like Paul Robeson, performed either at church or on stage, or even in movies, then negro spirituals were considered mainly as traditional songs. In the late 1930s, Sister Rosetta Tharpe dared sing Gospel songs in a nightclub. This was the very start of singing Gospel songs in many kinds of places: churches, theaters, concert halls. The number of quartets was high, at that time.

At the same time, some preachers and their congregations were also famous; some of them recorded negro spirituals and Gospel songs. Ministers, like James Cleveland, made tours with their choruses, in the United States and abroad.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, before and during rallies for Civil Rights, demonstrators sang negro spirituals. For example, “We Shall Overcome” and “This Little Light of Mine” were popular

After 1985

The first Dr Martin Luther King's Day was celebrated in 1985; it became a national holiday in 1992. This event is a milestone in the history of African American: it shows that the African American community is a part of the US nation. This Day is included in the month, when Black History is celebrated through various events.Since that first King’s Day, Negro spirituals have been considered as being pieces of the American heritage. So, they are often in the programs of events reminding Black History.

It appears that today everyone may perform Gospel music in the United States. The main issue is to know how to improve the African American integrity in singing negro spirituals and other Christian songs.

Know more on HistoryMore on the history of slavery, click hereOther documents about North American slaves “North American Slave Narratives” Know more on African American History, click here (MENC : National Association for Music Education) Facts of Black History, click here Some books to read Peter KOLCHIN, “American Slavery”, Penguin Books, London, New York, 1995 Joanna GRANT, « Black Protest. History, Documents and Analyses », Fawcett Premier, New York, 1968 Leon F. LITWACK “Trouble in Mind”, Vintage Books, New York, 1998 Robert S. STAROBIN, « Blacks in Bondage. Letters of American Slaves", Barnes and Noble Books, York, 1988 Benjamin QUARLES, « The Negro in the Making of America », A Touchstone Book Simon and Schuster Publ., 1996 Stephan THERNSTROM, Abigail THERNSTROM, « America in Black and White. One Nation Indivisible » A Touchstone Book Simon and Schuster Publ., 1999 |

This section is organized

by Spiritual Workshop, ParisMail to: question@negrospirituals.com

by Spiritual Workshop, ParisMail to: question@negrospirituals.com

http://www.negrospirituals.com/history.htm

-----------------

Join Canadian opera singer Measha Brueggergosman on a personal journey and historical quest as she performs an intensely powerful selection of spirituals. TV episodes air Fridays, Feb. 5, 12, 19 and 26 at 10pm ET / 7:30pm PT. The feature documentary airs Monday, Feb. 15 at Midnight ET/9pm PT and Tuesday, Feb. 16 at 9pm ET/ 6pm PT.

Who am I?

By Measha Brueggergosman, an award-winning

Canadian soprano who is recognized around the world for her spectacular

voice, innate musicianship, magnificent performance style and vibrant

personality. She has shared the stage with the likes of Bill Gates and

former U.S. President Bill Clinton and given performances for Nelson

Mandela, Kofi Annan and Queen Elizabeth II. At the 2010 Vancouver

Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, 3.2 billion television viewers from

across the globe witnessed her singing during the Opening Ceremonies.

Her musical range encompasses everything from gospel hymns and jazz

standards to classical music, as you will see for yourself throughout

this website.

By Measha Brueggergosman, an award-winning

Canadian soprano who is recognized around the world for her spectacular

voice, innate musicianship, magnificent performance style and vibrant

personality. She has shared the stage with the likes of Bill Gates and

former U.S. President Bill Clinton and given performances for Nelson

Mandela, Kofi Annan and Queen Elizabeth II. At the 2010 Vancouver

Olympic and Paralympic Winter Games, 3.2 billion television viewers from

across the globe witnessed her singing during the Opening Ceremonies.

Her musical range encompasses everything from gospel hymns and jazz

standards to classical music, as you will see for yourself throughout

this website.

I started classical piano and singing

lessons when I was seven years old. Now I am a classically trained opera

singer. I was strongly influenced musically by the Brunswick Street

Baptist Church, where I grew up watching my teacher perform every other

Sunday. He was a professional musician and from there my lessons began.

Getting that sort of musical engagement at such a young age was

essential – it encouraged me and made me realize that going into

classical music was possible. Once I dove into classical music, it

consumed me.

From the outside, classical music can seem extremely confining. There

are a lot of rules required to perfect the technique – but the result

can be extremely beautiful. You must allow the rules to free you instead

of constrain you.

From the outside, classical music can seem extremely confining. There

are a lot of rules required to perfect the technique – but the result

can be extremely beautiful. You must allow the rules to free you instead

of constrain you.

In classical music you’re a part of this huge tradition of singers and musicians who have come before you. The genre spans centuries and reflects many societies, so there is a lot I can draw from. I’m standing on the shoulders of some pretty great people. It allows me to be better than I actually am. But now that I’m 37, I want to expand on what I know. I’ve lived with this voice for so long that as my life experiences expand – challenging, joyful and opulent – I can’t help but want more. So now I have begun to explore African American spirituals.

My exploration of African-American spirituals is a way for me to challenge my classically trained mind. It is helping me to become a better musician. But there is another reason why spirituals are so important to me. I wanted to explore this repertoire because it’s dear to my heart. These spirituals are close to my Christian faith. They are also a very important part of my family’s history. It is the music of my people. My ancestors were stolen from Africa and sold into slavery in the United States before finding freedom in Nova Scotia. The spirituals were born out of a time when my people were oppressed and needed to find a way not only to communicate with each other, but also to express themselves. They created a powerful snapshot of their lives that still resonates with people today. The reason the songs survived so long is because of their immediacy. They have the universality of a mournful yet hopeful existence. They have strength. Every group of people who have held their elbows out to create room for themselves has these kinds of songs. My people have spirituals, which played a huge part in how my ancestors came to be here – free, no longer owned, no longer stolen – on the east coast of Canada.

From the outside, classical music can seem extremely confining. There

are a lot of rules required to perfect the technique – but the result

can be extremely beautiful. You must allow the rules to free you instead

of constrain you.

From the outside, classical music can seem extremely confining. There

are a lot of rules required to perfect the technique – but the result

can be extremely beautiful. You must allow the rules to free you instead

of constrain you.

In classical music you’re a part of this huge tradition of singers and musicians who have come before you. The genre spans centuries and reflects many societies, so there is a lot I can draw from. I’m standing on the shoulders of some pretty great people. It allows me to be better than I actually am. But now that I’m 37, I want to expand on what I know. I’ve lived with this voice for so long that as my life experiences expand – challenging, joyful and opulent – I can’t help but want more. So now I have begun to explore African American spirituals.

My exploration of African-American spirituals is a way for me to challenge my classically trained mind. It is helping me to become a better musician. But there is another reason why spirituals are so important to me. I wanted to explore this repertoire because it’s dear to my heart. These spirituals are close to my Christian faith. They are also a very important part of my family’s history. It is the music of my people. My ancestors were stolen from Africa and sold into slavery in the United States before finding freedom in Nova Scotia. The spirituals were born out of a time when my people were oppressed and needed to find a way not only to communicate with each other, but also to express themselves. They created a powerful snapshot of their lives that still resonates with people today. The reason the songs survived so long is because of their immediacy. They have the universality of a mournful yet hopeful existence. They have strength. Every group of people who have held their elbows out to create room for themselves has these kinds of songs. My people have spirituals, which played a huge part in how my ancestors came to be here – free, no longer owned, no longer stolen – on the east coast of Canada.

Spirituals played a huge part in how my ancestors came to be here – free, no longer owned – on the east coast of CanadaI believe that life is about seeking freedom. Learning to be free is a lifelong process. I had to work for the freedom that I experience now. I try to feel as free as possible in all of my roles as a Christian, a human, a musician, a mom, and a wife, but some areas of my life are freer than others. Finding a way to let God control what can be controlled is helpful. It is so liberating for me. I don’t have to worry; His work is done with or without me. I’ve begun to realize that nothing is a mistake and I’m clearly meant to be here because I’ve been close to death several times. I can’t control things but I can react to things and I must do something with the time and the relationships I have.

halet Studio started out as a dream. It began with a search for property near Toronto. At first, everything was too expensive, until I noticed a property in Durham that had a stunning view of Lake Ontario and 40 acres of land. It was in the country but only 45 minutes from the city.

I’ve always loved the concept of a residential studio – a place where artists could stay as well as work, so they get away from it all in a place that inspires creativity. I wanted big windows so artists could be surrounded by nature. Most recording engineers toil in downtown studios with no connection to the natural environment. But in a country studio, you simply have to look out a window to connect with the natural world.

Now, as I look back at all the memorable sessions we’ve had in Chalet’s 30-year history, it seems unbelievable we have come this far. It wasn’t easy to get started. I was 25 years old at the time and I had just finished studying music at Carleton, York and Humber and spending several years with my band on the road. My wife, Sheila-Marie Richardson (“She” for short) and I were starting from the ground up, so we faced many hurdles, such as trying to attract staff and clients into the countryside and the costs of recording gear and building a professional-quality soundproof studio.

Now, as I look back at all the memorable sessions we’ve had in Chalet’s 30-year history, it seems unbelievable we have come this far. It wasn’t easy to get started. I was 25 years old at the time and I had just finished studying music at Carleton, York and Humber and spending several years with my band on the road. My wife, Sheila-Marie Richardson (“She” for short) and I were starting from the ground up, so we faced many hurdles, such as trying to attract staff and clients into the countryside and the costs of recording gear and building a professional-quality soundproof studio.

Chalet needed its first big client to put us on the map. We set our sights on Rush, one of the most recognizable bands in Canada. After many attempts at contacting their management, they told us our equipment wasn’t up to standard. They sent the long list of gear Chalet would need to get their business (and still, there were no guarantees).

I decided to go big or go home. I “rolled the bones” and re-mortgaged everything, purchased the needed equipment – and in the end one of Canada’s most iconic bands spent almost five months on their album Presto in our studio. To accommodate Rush we supplied a sound engineer, gourmet chef, daily maid service and a “handy man.” They always had a creative project on the go outside of their music, like “decorating” our old Dodge station wagon. Over time they came back to write three more records.

In 2001, She and I decided to take Chalet to the next level – we moved there permanently and turned it into a bed and breakfast as well as recording studio. With my family there, it was not uncommon for us to sit down at breakfast (or brunch, given that they were musicians) with the band in recording. This was something that many families would not be able to handle, but musicians are, as a rule, very polite and respectful, and really interesting people. To this day, we still grow wonderful friendships with many of our guests.

There are always challenges to deal with when you are running your own business, but because of our intense love of the space, the music created here and the people we meet, we continue to share our special way of life with others at the Chalet. We are hugely grateful for the many wonderful connections it continues to present.

When Measha was singing spirituals, it felt as if she was channeling a deep history of pain and struggle, and yet an astounding beauty resonated from her. It is deeply moving music, and, for these reasons, has lasted the test of time.

I’ve always loved the concept of a residential studio – a place where artists could stay as well as work, so they get away from it all in a place that inspires creativity. I wanted big windows so artists could be surrounded by nature. Most recording engineers toil in downtown studios with no connection to the natural environment. But in a country studio, you simply have to look out a window to connect with the natural world.

Now, as I look back at all the memorable sessions we’ve had in Chalet’s 30-year history, it seems unbelievable we have come this far. It wasn’t easy to get started. I was 25 years old at the time and I had just finished studying music at Carleton, York and Humber and spending several years with my band on the road. My wife, Sheila-Marie Richardson (“She” for short) and I were starting from the ground up, so we faced many hurdles, such as trying to attract staff and clients into the countryside and the costs of recording gear and building a professional-quality soundproof studio.

Now, as I look back at all the memorable sessions we’ve had in Chalet’s 30-year history, it seems unbelievable we have come this far. It wasn’t easy to get started. I was 25 years old at the time and I had just finished studying music at Carleton, York and Humber and spending several years with my band on the road. My wife, Sheila-Marie Richardson (“She” for short) and I were starting from the ground up, so we faced many hurdles, such as trying to attract staff and clients into the countryside and the costs of recording gear and building a professional-quality soundproof studio.

Chalet needed its first big client to put us on the map. We set our sights on Rush, one of the most recognizable bands in Canada. After many attempts at contacting their management, they told us our equipment wasn’t up to standard. They sent the long list of gear Chalet would need to get their business (and still, there were no guarantees).

I decided to go big or go home. I “rolled the bones” and re-mortgaged everything, purchased the needed equipment – and in the end one of Canada’s most iconic bands spent almost five months on their album Presto in our studio. To accommodate Rush we supplied a sound engineer, gourmet chef, daily maid service and a “handy man.” They always had a creative project on the go outside of their music, like “decorating” our old Dodge station wagon. Over time they came back to write three more records.

In 2001, She and I decided to take Chalet to the next level – we moved there permanently and turned it into a bed and breakfast as well as recording studio. With my family there, it was not uncommon for us to sit down at breakfast (or brunch, given that they were musicians) with the band in recording. This was something that many families would not be able to handle, but musicians are, as a rule, very polite and respectful, and really interesting people. To this day, we still grow wonderful friendships with many of our guests.

There are always challenges to deal with when you are running your own business, but because of our intense love of the space, the music created here and the people we meet, we continue to share our special way of life with others at the Chalet. We are hugely grateful for the many wonderful connections it continues to present.

we often grow wonderful friendships with many of our musical guestsAnd Measha is definitely one of those wonderful connections. She first came to Chalet in July 2014 to record her CD Christmas. Hosting Measha a few months later for Songs of Freedom was an extraordinary experience. Measha brought her own energy and intensity to the project, which was so inspiring. She is so talented; every person in the room was in awe while she sang. She has such control over her voice and can switch effortlessly from opera to jazz to pop to spirituals.

When Measha was singing spirituals, it felt as if she was channeling a deep history of pain and struggle, and yet an astounding beauty resonated from her. It is deeply moving music, and, for these reasons, has lasted the test of time.

The Meaning of Music

By Measha Brueggergosman, an award-winning Canadian soprano whose musical range encompasses everything from gospel hymns and jazz standards to classical music. Before beginning her journey into the world of spirituals, Brueggergosman discusses the significance of music in her life.

By Measha Brueggergosman, an award-winning Canadian soprano whose musical range encompasses everything from gospel hymns and jazz standards to classical music. Before beginning her journey into the world of spirituals, Brueggergosman discusses the significance of music in her life.

There are some people for whom classical music is their natural state of mind. They listen to it, they eat, sleep and breathe it and they don’t exist outside of it. I’m not like that. I like to maintain some objectivity. I like to see it in the context of other forms of music and other musicians. Coming from a classical music tradition, I am always grateful when I get to explore other types of music together with musicians whose focus isn’t classical music but who play mostly jazz, or country or blues, etc. Like here at the Chalet.

The musicians that I get to play with here are absolutely terrific. Sometimes they render me speechless. I go to them to learn more and just try to keep up. Singing non-classical music can be terrifying because the musicians I’m working with are so good. But they have pulled me forward. They have squeezed me out of the box.

The musicians that I get to play with here are absolutely terrific. Sometimes they render me speechless. I go to them to learn more and just try to keep up. Singing non-classical music can be terrifying because the musicians I’m working with are so good. But they have pulled me forward. They have squeezed me out of the box.

I sing to captivate an audience. They are glued to their seats and I’m the only one they’re looking at. When I am the focus of people’s attention, I like my audience to know that I showed up on purpose, for them. I’ve learned to take that attention and run with it. And I want people to know how grateful I am that they’re there.

The musicians that I get to play with here are absolutely terrific. Sometimes they render me speechless. I go to them to learn more and just try to keep up. Singing non-classical music can be terrifying because the musicians I’m working with are so good. But they have pulled me forward. They have squeezed me out of the box.

The musicians that I get to play with here are absolutely terrific. Sometimes they render me speechless. I go to them to learn more and just try to keep up. Singing non-classical music can be terrifying because the musicians I’m working with are so good. But they have pulled me forward. They have squeezed me out of the box.Recording classical music is a spiritual experienceRecording classical music is a spiritual experience. A lot of bodies, histories, insecurities and strengths are coming together in the same room, and I’m usually at the centre of it. I’m the soloist. I’m usually the reason that all of these people have come together, so I feel responsible for the atmosphere in the room. I feel very comfortable creating a dynamic for a group and dictating the tenor of a room. You can’t be a performer and not care about the state of the room where you’re performing. Eventually you get to the aspect of your technique that involves reading, guiding and molding the experience in a room. And you have to believe that you have that much sway and influence over how people feel.

I sing to captivate an audience. They are glued to their seats and I’m the only one they’re looking at. When I am the focus of people’s attention, I like my audience to know that I showed up on purpose, for them. I’ve learned to take that attention and run with it. And I want people to know how grateful I am that they’re there.

African-American Spirituals:

Music of the Slaves

By Calvin Earl, writer, lecturer, composer and ambassador for the legacy and teachings of African American spirituals and the oral history of the slaves. In 2007 he spearheaded a movement that encouraged the U.S. Congress to unanimously vote to recognize African-American spirituals as a national treasure and to honor the slaves for their contributions to the United States.

By Calvin Earl, writer, lecturer, composer and ambassador for the legacy and teachings of African American spirituals and the oral history of the slaves. In 2007 he spearheaded a movement that encouraged the U.S. Congress to unanimously vote to recognize African-American spirituals as a national treasure and to honor the slaves for their contributions to the United States.

For thousands of years, human beings from around the world have sought comfort and connection. We build communities and seek safety, comfort and guidance through different practices like mantras, religious beliefs and non-religious practices; it was no different for the African slaves first arriving in the North American colonies in 1619. Throughout history and until 1865 when legal slavery came to an end in the United States, slaves were only considered three-fifths human. They were not allowed to have a voice, which made it difficult for them to have that essential outlet we all need to release our fears and burdens. They were not afforded the time or place to worship, build community or seek comfort and safety, so they created an original music to fulfill these needs. Slaves carved a place in history by creating the original music we know today as spirituals.

Spirituals are a rare and distinctive type of song, a song of the human spirit created by enslaved Africans in and on their way to the United States. Spirituals are the voice of slaves expressing their own humanity through song. The true essence of any spiritual is that sacred inner voice of a slave seeking to connect with the source of all creation and to tell their story and have their very existence avowed. This music encouraged the slaves to stay focused on freedom, because the songs affirmed that one day it would belong to them. These songs encompass a gut-wrenching universal cry for freedom that all humanity seeks across time – the emotion is pure, raw and unadulterated.

Spirituals are a rare and distinctive type of song, a song of the human spirit created by enslaved Africans in and on their way to the United States. Spirituals are the voice of slaves expressing their own humanity through song. The true essence of any spiritual is that sacred inner voice of a slave seeking to connect with the source of all creation and to tell their story and have their very existence avowed. This music encouraged the slaves to stay focused on freedom, because the songs affirmed that one day it would belong to them. These songs encompass a gut-wrenching universal cry for freedom that all humanity seeks across time – the emotion is pure, raw and unadulterated.

One of the most powerful emotions to drive humanity is our deeply rooted yearning to have our voices heard and acknowledged. By connecting to each other through song, slaves were able to heal their pain, teach their young, record their history and communicate life-saving messages. Literally speaking, the lyrics of many spirituals facilitated secret conversations between slaves without alerting their masters and arousing suspicion. Slaves often used spirituals as a tool for navigation and advice about the Underground Railroad, a 19th century network of paths and safe houses in the United States that led escaping slaves to freedom in what would become Canada.

If you listen to the lyrics, most spirituals refer to death or crossing over into an afterlife where slavery doesn’t exist; the secret meaning behind this told slaves, “If you use the Underground Railroad, you don’t have to die to remove yourself from slavery.” That is true for “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The secret code in this song is the word “low,” which referred to the Deep South. In other words, the song was saying, “Lift me out of the South and out of slavery and carry me to freedom in the North.”

“Go Down Moses” was a forbidden song for the slaves, as their masters knew it was a song about escaping slavery. The slaves connected with the Biblical story of Moses leading his people to freedom. The song enlivened and inspired enslaved people and made it harder for their masters to control them. Harriet Tubman, who became known as the Moses of her people, would often defy her masters and sing that song at the top of her lungs.

The spiritual “Wade in the Water” is filled with specific instructions for escaping slaves. For an example right from the title, the song was providing a tip, telling escaping slaves that if they could wade in water, the hound dogs that slave masters sent out to find them wouldn’t be able to pick up their scent. The spiritual “Deep River” has a similar theme. In it, the Jordan River is code for the Ohio River; if you could get across the Ohio River you could live in freedom.

When the Emancipation Proclamation became the law of the land in 1865, American culture underwent major transformation, and several years later that also became true for the spirituals. The musical art forms of jazz, blues, R&B and gospel began to appear, and all of these genres found their inspiration and foundation in the original sound of the spirituals. Gradually, the spirituals themselves were sung less and less frequently.

As the years passed, the spirituals were transformed into a musical performance genre under the direction of Ella Sheppard, a former slave who eventually became choir director of the Fisk Jubilee Singers at Fisk University. Fisk, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, provided educational opportunities to former slaves so they could better equip themselves to become prosperous citizens. The school was facing financial problems, and so with great trepidation and deep concern for the integrity of the spirituals, Sheppard finally made the painstaking decision to transform them into a choir format to save the university. With that, the Jubilee Singers, a nine-member student chorus, brought the spirituals to a world audience, which allowed them to send money back to the college during tours. It is important to note that any written musical arrangement of a spiritual is not authentic to the original intention of this musical genre, since by definition spirituals are passed on orally, but Ella took great care when reinterpreting these songs.

I learned to love the spirituals during my humble beginnings. I grew up extremely poor, in a sharecropper’s cabin with eight siblings. We didn’t have running water or indoor plumbing, and too many times we went without food. We moved frequently because my parents couldn’t afford rent; however, I vividly remember the first time I played a spiritual on my guitar. In that moment, the fears I had went away and I felt secure within myself. The stigma of growing up poor seemed to disappear. Each time I played, the spirituals made me feel whole again.

What inspires me most about the spirituals is that the slaves created this magnificent music in the midst of their own despair while in bondage. Their music was their voice. It was a vision of hope and courage beyond measure. As a descendant of slaves myself, I feel an overwhelming sense of pride in the slaves’ musical accomplishments and their contribution to building a nation. For me the spirituals taught me to never give up. When someone tells me I can’t do something, I refuse to accept that outcome. Instead I go within and listen to my heart.

Today I continue to do concerts and lectures on this subject, and welcome people to visit my website calvinearl.com for further information on the history of the African-American spirituals.

Spirituals are a rare and distinctive type of song, a song of the human spirit created by enslaved Africans in and on their way to the United States. Spirituals are the voice of slaves expressing their own humanity through song. The true essence of any spiritual is that sacred inner voice of a slave seeking to connect with the source of all creation and to tell their story and have their very existence avowed. This music encouraged the slaves to stay focused on freedom, because the songs affirmed that one day it would belong to them. These songs encompass a gut-wrenching universal cry for freedom that all humanity seeks across time – the emotion is pure, raw and unadulterated.

Spirituals are a rare and distinctive type of song, a song of the human spirit created by enslaved Africans in and on their way to the United States. Spirituals are the voice of slaves expressing their own humanity through song. The true essence of any spiritual is that sacred inner voice of a slave seeking to connect with the source of all creation and to tell their story and have their very existence avowed. This music encouraged the slaves to stay focused on freedom, because the songs affirmed that one day it would belong to them. These songs encompass a gut-wrenching universal cry for freedom that all humanity seeks across time – the emotion is pure, raw and unadulterated.

One of the most powerful emotions to drive humanity is our deeply rooted yearning to have our voices heard and acknowledged. By connecting to each other through song, slaves were able to heal their pain, teach their young, record their history and communicate life-saving messages. Literally speaking, the lyrics of many spirituals facilitated secret conversations between slaves without alerting their masters and arousing suspicion. Slaves often used spirituals as a tool for navigation and advice about the Underground Railroad, a 19th century network of paths and safe houses in the United States that led escaping slaves to freedom in what would become Canada.

The true essence of any spiritual is that sacred inner voice of a slave seeking to have their very existence avowedAccording to Frederick Douglass and Harriet Tubman, both escaped slaves and leaders of the abolitionist movement, it was widely known to slaves that north of the American border was a refuge from slavery. Spirituals had a dual meaning for slaves as both a guide to the Underground Railroad and to life. For instance, in the spiritual “I’m on My Way to Canaan Land,” the word “Canaan” not only meant Heaven, it also meant north and specifically it referred to the British colonies that became Canada. Once across the border, former slaves and their families continued to sing the songs of their ancestors, and the songs were passed down orally through the generations. As new members of the community in places like Upper Canada, escaped slaves introduced these songs to the local culture.

If you listen to the lyrics, most spirituals refer to death or crossing over into an afterlife where slavery doesn’t exist; the secret meaning behind this told slaves, “If you use the Underground Railroad, you don’t have to die to remove yourself from slavery.” That is true for “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.” The secret code in this song is the word “low,” which referred to the Deep South. In other words, the song was saying, “Lift me out of the South and out of slavery and carry me to freedom in the North.”

“Go Down Moses” was a forbidden song for the slaves, as their masters knew it was a song about escaping slavery. The slaves connected with the Biblical story of Moses leading his people to freedom. The song enlivened and inspired enslaved people and made it harder for their masters to control them. Harriet Tubman, who became known as the Moses of her people, would often defy her masters and sing that song at the top of her lungs.

The spiritual “Wade in the Water” is filled with specific instructions for escaping slaves. For an example right from the title, the song was providing a tip, telling escaping slaves that if they could wade in water, the hound dogs that slave masters sent out to find them wouldn’t be able to pick up their scent. The spiritual “Deep River” has a similar theme. In it, the Jordan River is code for the Ohio River; if you could get across the Ohio River you could live in freedom.

When the Emancipation Proclamation became the law of the land in 1865, American culture underwent major transformation, and several years later that also became true for the spirituals. The musical art forms of jazz, blues, R&B and gospel began to appear, and all of these genres found their inspiration and foundation in the original sound of the spirituals. Gradually, the spirituals themselves were sung less and less frequently.

As the years passed, the spirituals were transformed into a musical performance genre under the direction of Ella Sheppard, a former slave who eventually became choir director of the Fisk Jubilee Singers at Fisk University. Fisk, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, provided educational opportunities to former slaves so they could better equip themselves to become prosperous citizens. The school was facing financial problems, and so with great trepidation and deep concern for the integrity of the spirituals, Sheppard finally made the painstaking decision to transform them into a choir format to save the university. With that, the Jubilee Singers, a nine-member student chorus, brought the spirituals to a world audience, which allowed them to send money back to the college during tours. It is important to note that any written musical arrangement of a spiritual is not authentic to the original intention of this musical genre, since by definition spirituals are passed on orally, but Ella took great care when reinterpreting these songs.

I learned to love the spirituals during my humble beginnings. I grew up extremely poor, in a sharecropper’s cabin with eight siblings. We didn’t have running water or indoor plumbing, and too many times we went without food. We moved frequently because my parents couldn’t afford rent; however, I vividly remember the first time I played a spiritual on my guitar. In that moment, the fears I had went away and I felt secure within myself. The stigma of growing up poor seemed to disappear. Each time I played, the spirituals made me feel whole again.

What inspires me most about the spirituals is that the slaves created this magnificent music in the midst of their own despair while in bondage. Their music was their voice. It was a vision of hope and courage beyond measure. As a descendant of slaves myself, I feel an overwhelming sense of pride in the slaves’ musical accomplishments and their contribution to building a nation. For me the spirituals taught me to never give up. When someone tells me I can’t do something, I refuse to accept that outcome. Instead I go within and listen to my heart.

Today I continue to do concerts and lectures on this subject, and welcome people to visit my website calvinearl.com for further information on the history of the African-American spirituals.

Connecting Histories

By Aaron Davis, a composer, arranger and piano player. Aaron has been making music his entire life and is inspired by many genres, including jazz, classical, pop and world music. He has done orchestral and choral arrangements for many artists, including Holly Cole, Alison Krauss, Natalie McMaster, and Canadian Brass, and has scored more than 100 films. In 2006 Aaron started arranging and playing with singer Measha Brueggergosman.

By Aaron Davis, a composer, arranger and piano player. Aaron has been making music his entire life and is inspired by many genres, including jazz, classical, pop and world music. He has done orchestral and choral arrangements for many artists, including Holly Cole, Alison Krauss, Natalie McMaster, and Canadian Brass, and has scored more than 100 films. In 2006 Aaron started arranging and playing with singer Measha Brueggergosman.

I learned a lot from Songs of Freedom. The challenge of re-interpreting these spirituals was a welcome one for me. I never knew that “Amazing Grace” was written by the captain of a slave ship! I never knew that some spirituals, like “Wade in the Water,” had secrets in them that would help slaves escape to freedom. As a child I sang some of these songs with my family, such as “Swing Low Sweet Chariot” and “Go Down Moses.” Other songs, like “Deep River” and “I Surrender All” were introduced to me by Measha.

My mother, Natalie Zemon Davis, is a social historian who is known for her work in the Early Modern period (16th through 18th centuries), where she has studied many aspects of society, including, most recently, the slave trade in Suriname. My father Chandler Davis is a mathematician who also writes poetry and science fiction. My father and his father, my grandfather Horace were active in the 1960s civil rights movement in the United States. Horace was a Birthright Quaker, and his ancestors in that branch of the family were active in the fight against slavery in the United States in the 19th century.

My mother, Natalie Zemon Davis, is a social historian who is known for her work in the Early Modern period (16th through 18th centuries), where she has studied many aspects of society, including, most recently, the slave trade in Suriname. My father Chandler Davis is a mathematician who also writes poetry and science fiction. My father and his father, my grandfather Horace were active in the 1960s civil rights movement in the United States. Horace was a Birthright Quaker, and his ancestors in that branch of the family were active in the fight against slavery in the United States in the 19th century.

My great-great-grandfather, Norwood Penrose Hallowell, enlisted in the Union Army to fight in the American Civil War. He and his brother Edward Needles Hallowell were both commanders in the Massachusetts 54th and 55th, some of the first black regiments fighting the Confederacy. Norwood was wounded in the Battle of Antietam after he was shot in the arm. He continued to fight for fair payment for black soldiers in the Union Army after his injury made it impossible to fight in battle anymore.

His father, Morris Longstreth Hallowell (my great-great-great grandfather) lived in Pennsylvania and ran what was called a station in the Underground Railroad. Slaves on their way north to Canada would stop at his home and would then be transported to the next station in secret.

These Quaker ancestors were abolitionists when being an abolitionist ran contrary to the politics of the time. I’m proud that some of my ancestors stood up to fight against slavery and racism, and hope that in the future people will be judged by their actions and not by the colour of their skin or their ethnic background. I don’t know of any direct connection between my ancestors and Measha’s, but I learned that some of Measha’s ancestors on her mother’s side came to Canada via the Underground Railroad.

Below is an excerpt from my great-great-grandfather’s memoirs. He speaks about a time when his house was used as a part of the Underground Railroad.

When Measha I work together our approach varies from song to song, although usually Measha gives me a list of songs that she would like to sing and I go away and try to re-imagine them. For me this involves an initial step of thinking about the lyrics and figuring out what the melody and basic chord structure should be, as these are sometimes obscured by ornamentation or arrangements in other recordings. I try to keep the original melody intact as much as possible, but look for different harmonic, rhythmic and textural approaches to the music. I try to imagine how Measha would sound singing it. When I come up with something I like, I play it for Measha and she invariably has something to add, subtract or alter. Sometimes she will play references from different musical sources for me to influence the colour of the arrangement. Sometimes she likes what I’ve come up with as is, or sometimes she has a radically different idea that we pursue together.

My mother, Natalie Zemon Davis, is a social historian who is known for her work in the Early Modern period (16th through 18th centuries), where she has studied many aspects of society, including, most recently, the slave trade in Suriname. My father Chandler Davis is a mathematician who also writes poetry and science fiction. My father and his father, my grandfather Horace were active in the 1960s civil rights movement in the United States. Horace was a Birthright Quaker, and his ancestors in that branch of the family were active in the fight against slavery in the United States in the 19th century.

My mother, Natalie Zemon Davis, is a social historian who is known for her work in the Early Modern period (16th through 18th centuries), where she has studied many aspects of society, including, most recently, the slave trade in Suriname. My father Chandler Davis is a mathematician who also writes poetry and science fiction. My father and his father, my grandfather Horace were active in the 1960s civil rights movement in the United States. Horace was a Birthright Quaker, and his ancestors in that branch of the family were active in the fight against slavery in the United States in the 19th century.

My great-great-grandfather, Norwood Penrose Hallowell, enlisted in the Union Army to fight in the American Civil War. He and his brother Edward Needles Hallowell were both commanders in the Massachusetts 54th and 55th, some of the first black regiments fighting the Confederacy. Norwood was wounded in the Battle of Antietam after he was shot in the arm. He continued to fight for fair payment for black soldiers in the Union Army after his injury made it impossible to fight in battle anymore.

His father, Morris Longstreth Hallowell (my great-great-great grandfather) lived in Pennsylvania and ran what was called a station in the Underground Railroad. Slaves on their way north to Canada would stop at his home and would then be transported to the next station in secret.

These Quaker ancestors were abolitionists when being an abolitionist ran contrary to the politics of the time. I’m proud that some of my ancestors stood up to fight against slavery and racism, and hope that in the future people will be judged by their actions and not by the colour of their skin or their ethnic background. I don’t know of any direct connection between my ancestors and Measha’s, but I learned that some of Measha’s ancestors on her mother’s side came to Canada via the Underground Railroad.

Below is an excerpt from my great-great-grandfather’s memoirs. He speaks about a time when his house was used as a part of the Underground Railroad.

When Measha I work together our approach varies from song to song, although usually Measha gives me a list of songs that she would like to sing and I go away and try to re-imagine them. For me this involves an initial step of thinking about the lyrics and figuring out what the melody and basic chord structure should be, as these are sometimes obscured by ornamentation or arrangements in other recordings. I try to keep the original melody intact as much as possible, but look for different harmonic, rhythmic and textural approaches to the music. I try to imagine how Measha would sound singing it. When I come up with something I like, I play it for Measha and she invariably has something to add, subtract or alter. Sometimes she will play references from different musical sources for me to influence the colour of the arrangement. Sometimes she likes what I’ve come up with as is, or sometimes she has a radically different idea that we pursue together.

Measha first approached me about the possibility of working together in 2006. She was familiar with my arrangement and piano work with the Holly Cole Trio, a group I founded with vocalist Holly Cole and bassist David Piltch in the late 80s. I worked with Measha to arrange a repertoire that fit with both of our musical sensibilities and we performed on BRAVO TV’s Live At The Rehearsal Hall. In 2008 we performed at the Junos. Together, we produced and arranged her CD I’ve Got A Crush On You in 2012.

Measha is an amazing vocal talent. She breathes life and vitality into music with her voice, an instrument that is sweet, rich, expressive and powerful. She welcomes challenges and enjoys mixing idioms, such as singing “Embraceable You” as a reggae tune or “Amazing Grace” with an Appalachian style. She is inherently musical and has many interesting and unexpected ideas.

Measha is an amazing vocal talent. She breathes life and vitality into music with her voice, an instrument that is sweet, rich, expressive and powerful. She welcomes challenges and enjoys mixing idioms, such as singing “Embraceable You” as a reggae tune or “Amazing Grace” with an Appalachian style. She is inherently musical and has many interesting and unexpected ideas.I invite everyone to visit my website aarondavispiano.com to have a look at my other works.

http://www.songsoffreedom.ca/episodes/our_songs/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.