The Only

Thing Necessary For the Triumph of Evil is For Good Men (Women) to Do Nothing –

Edmund Burke – True Then True Now -

Canada’s Patrick LaMontagne

POSTED THIS BLOG ON SUNDAY 20 NOV... AND OF COURSE HAD TO SEE THIS.... DAMMM IT.... AM SO TIRED OF OUR TROOPS BLOOD BEING SPILT ON GREEDY MENS WARS...

Dont care for him #ScottTaylor because he takes pleasure in dirtying up our troops bravery and incredible accomplishments against all odds of a world of spoilt media indulgence vs daily pockets of miracles vs crawling in holes with the sewer rats destroying our planet with no rules or laws..just hate; .... but never miss a read... that's how good this guy is .... and always used to report his articles- which were never very good it seemed for troop morale.... this one is braver...\\\

ON TARGET: Canada hiding bravery of its best

Last week, the Canadian military told reporters that our special forces operatives in northern Iraq have been involved in numerous firefights in recent weeks with the Daesh evildoers.

After photos had appeared on Facebook showing Canadian soldiers firing anti-armour missiles on the front lines, it was not surprising that DND confirmed this to be the case.

According to Maj.-Gen. Mike Rouleau, commander of the Canadian Special Operations Forces (CANSOFCOM), there have been three separate occasions wherein our soldiers engaged Daesh would-be suicide bombers with sophisticated anti-armour missile systems.

For those who have been following the now weeks-long allied offensive to recapture the Iraqi city of Mosul from Daesh, it is widely known that the evildoers have employed a multitude of suicide car bombs.

Rouleau explained: “The Kurds do not possess weapons like we have. So our three engagements with anti-armour weapon systems prevented that from happening several thousand metres before they wanted to detonate.” So far, so good. Our commandos are blasting apart the Daesh bad guys on the battlefield.

But that sounds like combat, and as we have been told repeatedly by both the former Conservative government and the current Liberal government, Canada does not have a combat mandate in Iraq.

To make the distinction clear, Rouleau stressed to reporters the fact that Canadian troops are not leading the fight, nor are they engaged in “offensive combat operations.” Digging himself in deeper, Rouleau added, “We have never accompanied any leading combat elements. My troops have not been engaged in direct combat as a fighting element in offensive combat operations.”

Huh? How can these Canadian soldiers firing anti-armour missiles not be with a leading combat element, if the only thing in front of them are the Daesh attackers? As for offensive operations, the entire push into Mosul and the recapture of its surrounding villages is one massive offensive. The Daesh suicide vehicles are desperate counterattacks to slow down the allied advance. It is a hell of a stretch of logic to push right up to the Daesh front lines and then proclaim your actions to be self-defence and, somehow, not combat.

Sticking to his guns, Rouleau tried to portray his soldiers’ actions as those of helpful bystanders who will engage Daesh with sniper fire or airstrikes to defend the Kurdish fighters they are supposed to be training. “From deliberately selected positions that maximize our utility to advancing Kurd forces, we have either defended ourselves, defended friendly forces, or defended civilians caught in the middle,” explained Rouleau.

Forgetting the fact that Rouleau’s statement of directly supporting “advancing Kurd forces” contradicts his earlier claim of having “never accompanied any leading combat elements,” it brings to mind the old axiom that if the enemy is within range of you, then you are within range of the enemy.

The crazy part of all this is that most Canadians do not care that our special forces personnel are engaged in combat with Daesh, even though they do not have a mandate to do so. The Daesh evildoers are mass murderers, rapists and perpetrators of attempted genocide. There is no doubt a sense of perverse pride among the Colonel Blimp warmongers that Canada is actively engaged in this shooting war. However, Canadian generals just can’t admit it.

I have stated repeatedly that, in my opinion, Canadian soldiers are not among the best in the world — they are the best. Our special forces operatives are undoubtedly a tremendous asset to the Kurdish forces they are supporting in battle. I am also sure that several of our soldiers have performed acts of heroism that would be worthy of medals of valour. However, due to the deliberate duplicity of our senior commanders in redefining the term combat in order to exceed their politically mandated ‘advise and assist’ role, these soldiers are not getting full credit for their service.

We can’t praise Canadian soldiers for their prowess in combat because, officially, they cannot be in combat.

http://thechronicleherald.ca/opinion/1417379-on-target-canada-hiding-bravery-of-its-best

-------------

The Story of Two Wolves who live within each of us ...... WAR AND PEACE.... who wins.... whichever u feed

www.youtube.com/watch?v=E8CHjX8HauA

-----------------

---------------

-------------------------

Colonialism and Imperialism, 1450–1950

von by Benedikt Stuchtey Original aufOriginal in German, angezeigt aufdisplayed in EnglischEnglish

▾

PublishedErschienen: 2011-01-24

▾

PublishedErschienen: 2011-01-24

The colonial encirclement of the world is an integral component of European history from the Early Modern Period to the phase of decolonisation. Individual national and expansion histories referred to each other in varying degrees at different times but often also reinforced each other. Transfer processes within Europe and in the colonies show that not only genuine colonial powers such as Spain and England, but also "latecomers" such as Germany participated in the historical process of colonial expansion with which Europe decisively shaped world history. In turn, this process also clearly shaped Europe itself.

- InhaltsverzeichnisTable of Contents

Introduction

In world history, no continent has possessed so many different forms of colonies and none has so incomparably defined access to the world by means of a civilising mission as a secular programme as did modern Europe. When Spain and Portugal partitioned the world by signing the Treaty of TordesillasWhat is now understood as globalisation has a critical background in the world historical involvement of the non-European sphere from the Early Modern Period up and into the period of decolonisation. No European country remained exempt – all directly or indirectly participated in the colonial division of the world. The Treaty of Tordesillas (1494) put global power thinking into words that perceived of colonial possessions as a political, economic and cultural right, last not least even as an obligation to a civilizing mission that was only definitively shaken with the independence of India in 1947.1 These two dates mark the start and decline of a key problem in the history of Europe, perhaps even its most momentous, that the always precarious colonial rule caused complex competitions among Europeans just as much as among the indigenous population in the colonies, that it was able to simultaneously create cooperation and close webs of relationships between conquerors and the conquered, and that it was never at any time free of violence and war, despotism, arbitrariness and lawlessness. This turns the simultaneity and multitude of European colonialisms and imperialisms into a border-bridging experience. Few transnational specifics of European history illustrate the diversity of a European consciousness this clearly.

But what was colonialism? If one looks back at the essential elements in the thought of the Spanish world empire since the 16th century, it was similar to that of the English and Portuguese up to the most recent time because of the often claimed idea that the European nations created their empires themselves without the participation of others. Conquest followed discovery: Christopher Columbus (c. 1451–1506) landed in 1492 on a West Indian island that he called San Salvador to emphasize the religious character of taking possession.

Colonialism and Imperialism

According to Wolfgang Reinhard, colonialism in terms of a history of ideas constitutes a "developmental differential" due to the "control of one people by an alien one".4 Unlike the more dynamic, but also politically more judgmental and emotionally charged form of imperialism, colonialism as the result of a will to expand and rule can initially be understood as a state that establishes an alien, colonial rule. It has existed in almost all periods of world history in different degrees of expression. Even after the official dissolution of its formal state in the age of decolonisation, it was possible to maintain it as a myth, as in Portugal after the Carnation Revolution in 1974, when the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar (1889–1970) was debated but hardly ever the colonial past in Angola, Mozambique, Goa, Macao and East Timor. Already in 1933, the Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre stated the thesis that the Portuguese as the oldest European colonial nation had a special gift for expansion in his controversial book Casa-grande e Senzala (The Masters and the Slaves). It consisted of peacefully intermingling the cultures without racism and colonial massacres. Using the example of Brazil, he rationalized colonial paternalism with the allegedly successful relationship between masters and slaves.But other colonial powers also claimed this for themselves. Even the harshest critics of expansion policies – starting with Bartolomé de las Casas (1474–1566) to the Marxist-Leninist criticism of the 20th century – did not doubt the civilising mission that justified colonial hegemony.5 Similar to the abolitionists, they criticised the colonial excesses that could mean mismanagement, corruption and, in the extreme case, genocide. However, that the colonies became an integral part of the mother country, that therefore the colonial nation is indivisible, at home on several continents and, thus, incapable of doing any fundamental evil, can be shown to be part of the European colonial ideology since its earliest beginnings. Intellectual transfer processes had already taken place at this time, in the Age of Enlightenment most noticeably in the mutual influence of Adam Smith (1723–1790), Denis Diderot (1713–1784), Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)[

When, during the course of the 19th century, the Italians, Belgians and Germans raised a claim to their share of the world in addition to the old colonial powers, the term "Imperialism" became an ideologically loaded and overall imprecise, but probably irreplaceable historiographical concept.7 During the phase of High Imperialism between 1870 and World War I, every larger European nation state as well as the USA and Japan participated in acquiring territories outside Europe. That is what makes this period so unique in European history, though measured against other criteria, such as time and space, it was not more spectacular than previous ones. Thus, the European conquest of North and South America in the 16th and 17th centuries or of India in the 18th and early 19thcenturies was no less incisive in its spatial dimension or the number of people brought under European rule as was the "Scramble for Africa" that became synonymous with the unsystematic and overly hasty intervention of Europeans in the entire African continent. But unlike in earlier periods, a broad European public for the first time participated politically, economically and culturally directly in the process of that expansion. It had deep-reaching effects on the historical development of the European societies themselves, which is reflected, for example, in the professional careers of politicians, diplomats and high-ranking military men. After all, it was caused by massive economic and diplomatic rivalries between the European colonial powers and a widespread chauvinism.

Likewise, this process was to a significant extent triggered by internal crises in Africa itself. As in the 16th century, the rivalry between Christian and Islamic missions again erupted in the North of Africa. In a classic of the historiography of imperialism, Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher explain that Europe is not the only place for understanding the motives of European expansion. According to Robinson and Gallagher, this motivation was primarily founded in Africa, at least, as far as late Victorian society was concerned.8 If non-Western societies were no longer just the victims of Europe and quite a few of their elites participated in colonial and imperial rule, a layer of European settlers, Christian missionaries, colonial officers etc., who bridged the "periphery" and the "centre", became a third force known in research as the "men on the spot". Their lobbying influence on the expansion of the colonial empires was no less than that of political and economic interest groups in the metropole, even though their motivations depended more situationally on the events in the colonies than could be or would be the case in the European centres of power. This can be shown equally for the Asian, the African and the Pacific regions. Colonial sites of remembrance and their culture of monuments recall to this day conflicts and ambivalences of European colonial rule in public memory.9

This circumstance made High Imperialism a European and global project at both the centre and the periphery. Furthermore, it illustrates the critical significance of political and military force in the imperial process. "Gunboat diplomacy", one of the historical buzzwords for Europe's intercourse with Africa in the final third of the 19th century, also occurred in Turkey and China. Informal imperialism, often equated with the dominance of free trade over other methods of colonial influence, lost ground to the extent that coercion could only be exercised by violence. This is well illustrated by the war with China over the opium trade (1840–1842). The brutal suppression of the Indian "mutiny" in 1857/1858 by the British

Nevertheless, the "informal empire" was the prevailing model. In the British context, this led to the exaggerated thesis that the nation was not interested in expansion and that in this regard it was characterized by "absentmindedness".10 Those who currently perceive global capitalism as the successor of formerly direct territorial rule because it exercises no less pressure on the political and social systems to impose its economic interests, see the origins of informal imperialism reaching deep into the 19th century. Until the recent past, this thesis could be countered by noting that it not only underestimates the scale of the creation of global empires but also their dissolution.11 The consequences of the problematic withdrawal of the French from Algeria, the Italians from Eritrea or the British from India and Ireland still remain present. In this respect, colonisation and decolonisation were two historical processes referring to each other, comparable to the systole and diastole of the metropolitan heart beat. Only the interaction of these two as well as numerous other factors resulted in the world historical consequences of European expansion.

Regions and periods

Colonial regions and their limits as well as periods and their caesuras offer two possibilities of approaching European colonialism. For example, the independence of the North American colonies in 1776[In 1772, when governor Warren Hastings (1732–1818)[

South Africa, since the 17th century developed by the Dutch as a settlement colony and since 1815 of importance to the British because of its gold and diamond mines, is exempted from this. Similar to Egypt, it played a special role, including with regard to its perception by Europeans. The shipping routes around the Cape and through the Suez Canal were of elementary significance from the perspective of military and commercial politics. Furthermore, a presence in Egypt held great symbolic significance, as manifested in attempts at its conquest from Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) to Adolf Hitler (1889–1945). Remarkable in this parallel is the belief that focussed power in Europe and on the Nile – as the access to Asia – was a condition of concentrated power in the world. A British colonial administrator such as Evelyn Baring, Lord Cromer (1841–1917), who was stationed in Calcutta and Cairo, knew like none other that the survival of the empire depended as much on India, the Jewel in the Crown, as on the Suez Canal. His book Ancient and Modern Imperialism (1910) is a testimonial of intimate knowledge of the manner in which colonial rule functioned, as they were handed down at various administrative posts. What the British were willing to spend on the defence of their interests some 6,000 miles from London is evident from the, on the whole devastating, South African War (also Second Boer War, 1899–1902).

Precisely defined dividing lines between periods are impossible in this panorama as a matter of course. For this, the enterprises in which all European colonial powers were more or less involved (voyages of discovery, scientific projects such as cartography, construction of mercantilist colonial economies etc.) were too different in their time spans and too fluid, while the interactions between Europe and the rest of the world, which were subjected to continuous change, were too divergent. However, there were phases in the overall development of European colonialism that can be separated in analogy to the development of the great power system of the European states:

1. In the beginning, Portugal and Spain (in personal union 1580–1640) were primarily interested in overseas trade to Brazil and the Philippines and inspired by Christian missionary zeal. With few exceptions, they managed to avoid colonial overlap.

2. By contrast, competition heated up in the 17th century, when the English, French and Dutch pressed forward, initially not in the territories of the Spaniards and the Portuguese, but in neighbouring regions. This is demonstrated in exemplary manner by the North American Atlantic coast between the French possessions in modern Canada and the Spanish claims in the South.

3. When it became impossible to avert the crisis of the Ancien Régime in Europe any longer, the colonial empires also lost their cohesion. The British won against their French rival in North America and India, against the Dutch in Southeast Asia and against the Spanish in South America. The independence of the United States was substituted with supremacy in India, in South Africa and especially on the seas with the almost peerless Royal Navy and modern free trade.

4. The colonial incorporation of Africa on a large scale began with France's conquest of Algeria in 1830, which at the same time more than before released Europe's internal economic and industrial tensions as colonialist forces and peaked in High Imperialism between 1870 and World War I.12

5. Since the origins of a pluralistic colonial system during the course of the 19th century, not only the Europeans were involved in dividing the world but also Japan and Russia. The USA is the prototype for a successful linkage of continental internal colonisation in the form of the westward shift of the Frontier and maritime colonial policy in the Asian sphere, while paradoxically being the most successful model of anti-colonialism. At the latest around 1900, the European system of great powers stood before the challenge of global competition. In the controversial interpretation of Niall Ferguson, it was logical that the USA would assume Britain's role as the "global hegemon" in the 20th century and marginalize the formal and informal colonialism of Europe but also continue globalization as "anglobalisation".13

Forms

Since the 16th century, genuine European colonial powers such as Spain, Portugal, France and Britain were distinguished by developing a concept of their world rule and basing it on the legacy of Rome.14 This does not mean that stragglers like Italy, Belgium and Germany did not produce their own forms of imperial thought and had specific colonial systems with which they caught up to the great historical empires. German colonial officials, pragmatists such as Heinrich Schnee (1871–1949) and Carl Peters (1856–1918)[The empires of the modern nation state were not exposed to a loss of unity associated with the global dimension. Their expansion drive was primarily conditioned by worldly factors such as profit and prestige, in any case not a concept of universal monarchy indebted to Christian salvation, peace and justice. The world empire thought of Charles V (1500–1558) survived to the extent that the civilising mission of the modern European imperialisms became a transnational, but not primarily religious motor. Their driving forces were very different, not necessarily ideological but, in the French case, they constituted a part of the cost/benefit calculation. In 1923, Albert Sarraut (1872–1962)[

That this rule could apply to the overseas empires but would be different for continental ones like that of the Habsburgs was discussed by contemporary observers in the Austro-Hungarian monarchy's sphere of influence and especially in delimitation against the pulsating German empire. Austrian imperial history was formulated in imperial terminology – after all, the occupation of Bosnia-Herzegovina was officially accepted at the Congress of Berlin in 1878. However, the Habsburg Empire was not centralistic but multinational in concept and tolerated local independence up to the confirmation of regional and religious diversity. Habsburg's deficit of not being able to provide a national identity was partially compensated by strengthening the popular dynasty, although it, in the person of Emperor Franz Joseph (1830–1916), was not equal to the extreme High Imperialism of the turn of the century. The empire was governed in a nostalgic rather than modern manner. Where similar backward tendencies appeared in other European monarchies, a balance was sought using political and cultural measures. One of the best known examples is the crowning of Victoria (1819–1901) as the empress of India in 1876, which was in a manner an imitation of the Bonapartist succession practice of the Spanish monarchy in South America. Benjamin Disraeli (1804–1881) pushed Victoria's imperial title forward because he saw a crisis coming toward Britain and the empire with the monarch's Germanism and obliviousness to duty after the death of her prince consort Albert (1819–1861). Subsequently, British imperialism became even more unrivalled and the centrality of Europe in the world of the 19th century became even more clearly an economic, military and maritime centrality of Great Britain. Based on the Royal Navy and world trade, the Pax Britannica symbolized this programme of a pacifist colonialism. In the concept of a peace-making world empire, there could be several global players but only one global hegemon. This idealisation of maritime rule was reflected in Alfred Mahan's (1840–1914) classic The Influence of Sea Power upon History (1890), a manifesto of the triumphal "anglobalisation", that is the earth-girding and people-uniting expansion of the Occident.

The overseas as well as the continental colonial empires of Europe were together characterised by constructing their imperial rule over a developmental differential against the "Other" and, thus, significantly contributed to a changed self-perception of Europe in the world. Essentially, it was more about self-image than the image of others. Rule was alien rule over peoples perceived as being "subject". It had to be achieved with violent conquest and secured with colonial methods to guarantee economic, military and cultural exploitation. Therefore, the European claim to superiority legitimised the logic of the unequal interrelationship between colonial societies and a novel capitalism in Europe, especially the British "gentlemanly capitalists",19 whose global reach came to bear in a particularly pronounced form as the slave economy. Nowhere was the ambivalence between ruthless hegemonic ambition on one hand and concepts such as world citizenship, cosmopolitanism and human rights, which were derived from the Enlightenment, more clear than in slavery on the other hand.20 Slavery, which made use of the idea of the different natures of people, culminated in the race theories of High Imperialism. Probably no European colonial power remained aloof from this discussion, which with the help of medicine, anthropology, ethnology etc. was founded on pseudoscience, guided by practical benefit and brought the contradictions and perversions of imperialism to a climax. French debates from Arthur de Gobineau's (1816–1882) Essai sur l'inégalité des races humaines, 1853)

Outlook

Therefore, the concept of a "Europeanisation of the world" signifies the dilemma. On one hand, there are positive achievements, such as modern statehood, urbanisation, rationalism and Christianity, European thought systems such as Liberalism, Socialism and Positivism, which was received with great enthusiasm in France and England as well as in Brazil and Japan. On the other hand, there are negative legacies, such as Caesarism, racism and colonial violence. It can also raise the question whether European history between about 1450 and 1950 cannot be predominantly read as a history of expansion, especially if one treats the history of the empires beyond Eurocentrism as world history but without underlaying it with a universal theory and without constructing it as a historical unity. With the treaty to divide the world of 1494, a more intensive interaction of nation, expansion and "Europeanisation of the world" began that was not a unilateral creation of dependencies but a process of give and take with reciprocal influences beyond fixed imperial boundary drawing. According to this multipolar dynamic, Europe was not decentralised or provincialised,21 but Europe is equally unsuitable as the only perspective in the interpretation of the global modern period.22Appendix

Literature

Aldrich, Robert: Vestiges of the Colonial Empire in France: Monuments, Museums and Colonial Memories, Basingstoke 2005.Barth, Boris / Osterhammel, Jürgen (eds.): Zivilisierungsmissionen: Imperiale Weltverbesserung seit dem 18. Jahrhundert, Constance 2005.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh: Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference, New Jersey 2000.

Cain, Peter J. / Hopkins, Antony G.: British Imperialism: Innovation and expansion 1688–1914, 2. ed., London 2001.

idem: British Imperialism: Crisis and deconstruction 1914–1990, 2. ed., London 2001.

Dilke, Charles Wentworth: Problems of Greater Britain, London 1890, vol. 1–2.

Drescher, Seymour: Abolition: A history of slavery and antislavery, Cambridge et al. 2009.

Elliott, John H.: Empires of the Atlantic World: Britain and Spain in America, 1492–1830, New Haven et al. 2006.

Ferguson, Niall: Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World, London 2003.

Froude, James Anthony: Oceana, or England and her colonies, London 1886.

Headley, John M.: The Europeanization of the World: On the Origins of Human Rights and Democracy, Princeton et al. 2008.

Kiernan, Victor: The Lords of Human Kind: European Attitudes to Other Cultures in the Imperial Age, London 1995.

Koebner, Richard / Schmidt, H. D.: Imperialism: The story and significance of a political word, Cambridge 1965.

Korman, Sharon: The Right of Conquest: The acquisition of territory by force in international law and practice, Oxford 1996.

Mommsen, Wolfgang J.: Der europäische Imperialismus: Aufsätze und Abhandlungen, Göttingen 1979.

Oliveira Marques, Antonio Henrique de: Geschichte Portugals und des portugiesischen Weltreichs, Stuttgart 2001.

Osterhammel, Jürgen: Kolonialismus: Geschichte, Formen, Folgen, 5. ed., Munich 2006.

Pagden, Anthony: Lords of all the World: Ideologies of Empire in Spain, Britain and France c. 1500 – c. 1800, New Haven 1995.

Porter, Andrew: European Imperialism, 1860–1914, Houndmills 1994 (Studies in European History).

Porter, Bernard: The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain, Oxford et al. 2004.

Reinhard, Wolfgang: Kleine Geschichte des Kolonialismus, Stuttgart 2008.

Robinson, Ronald / Gallagher, John: Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism, London 1961.

Sarraut, Albert: La mise en valeur des colonies Françaises, Paris 1923.

Seeley, John Robert: The Expansion of England, London 1883.

Stuchtey, Benedikt: Die europäische Expansion und ihre Feinde: Kolonialismuskritik vom 18. bis in das 20. Jahrhundert, Munich 2010.

Wesseling, Hendrik L.: The European Colonial Empires 1815–1919, Harlow 2004.

Notes

- ^ Korman, Right of Conquest 1996.

- ^^ Digitized version of the peace treaty, Ministère des Affaires étrangères, online: http://www.doc.diplomatie.gouv.fr/BASIS/choiseul/desktop/choiseul/DDW?M=134&K=17630001&W=PAYS+%3D+%27Multilat%E9raux%27+ORDER+BY+SOUSSERIE/Ascend [20.09.2010].

- ^ Oliveira Marques, Geschichte Portugals 2001, p. 177.

- ^ Reinhard, Kolonialismus 2008, p. 1.

- ^ Barth / Osterhammel, Zivilisierungsmissionen 2005.

- ^ Stuchtey, Europäische Expansion 2010, p. 39–122.

- ^ Koebner / Schmidt, Imperialism 1965, passim.

- ^ Robinson / Gallagher, Africa 1961, pp. 462–472.

- ^ Cf. Aldrich, Vestiges 2005, pp. 328–334.

- ^ Seeley, Expansion 1883.

- ^ Porter, Absent-Minded Imperialists 2004.

- ^ Wesseling, European Colonial Empires 2004.

- ^ Ferguson, Empire 2003.

- ^ Pagden, Lords 1995, pp. 11–28.

- ^ Elliott, Empires 2006, passim.

- ^ Sarraut, Valeur 1923.

- ^ Seeley, John Robert: The Expansion of England, London 1883; Dilke, Charles Wentworth: Problems of Greater Britain, London 1890, vol. 1–2.

- ^ Froude, Oceana 1886, pp. 1–17.

- ^ Cain / Hopkins, Imperialism 2001.

- ^ Drescher, Abolition 2009.

- ^ Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe 2000.

- ^ Headley, Europeanization 2008.

Dieser Text ist lizensiert unter This text is licensed under: CC by-nc-nd 3.0 Germany - Attribution, Noncommercial, No Derivative Works

Übersetzt von:Translated by: Michael Osmann

Fachherausgeber:Editor: Johannes Paulmann

Redaktion:Copy Editor: Jennifer Willenberg

Eingeordnet unter:

"Columbus taking possession of the new country" 1893

"Columbus taking possession of the new country" 1893  "The West"

"The West"  "Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorin of Calicut", c. 1905

"Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorin of Calicut", c. 1905  Abolitionism in the Atlantic World

Abolitionism in the Atlantic World  Albert Sarraut (1872-1962)

Albert Sarraut (1872-1962)  Alliances and Treaties

Alliances and Treaties  Animals

Animals  Battle in the Second Boer War 1899

Battle in the Second Boer War 1899  Border Regions

Border Regions  Carl Peters (1856–1918)

Carl Peters (1856–1918)  Catholic Mission

Catholic Mission  Censorship and Freedom of the Press

Censorship and Freedom of the Press  Christian Mission

Christian Mission  Civil Society

Civil Society  Colonial Exhibitions and 'Völkerschauen'

Colonial Exhibitions and 'Völkerschauen'  Colonial Law

Colonial Law  Colonialism and Imperialism

Colonialism and Imperialism

Colonialism and Imperialism

Colonialism and Imperialism  Cultural Transfer

Cultural Transfer  Introduction

Introduction  East Central Europe

East Central Europe  Economic Networks

Economic Networks  Economic Relations

Economic Relations  Emigration: Europe and Asia

Emigration: Europe and Asia  English Cartoon on the Indian Rebellion of 1857

English Cartoon on the Indian Rebellion of 1857  Mosaic of Languages

Mosaic of Languages  Freemasonries, 1850–1935

Freemasonries, 1850–1935  Food and Drink

Food and Drink  Free Trade

Free Trade  Italian Cuisine

Italian Cuisine  From the "Turkish Menace" to Orientalism

From the "Turkish Menace" to Orientalism  Globalization

Globalization  Herero Prisoners of War in German Southwest Africa 1904

Herero Prisoners of War in German Southwest Africa 1904  Islamic Law and Transfer of Law

Islamic Law and Transfer of Law  Jewish Migration

Jewish Migration  Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)  John Trumbull (1756–1843), Declaration of Independence 1818

John Trumbull (1756–1843), Declaration of Independence 1818  Knowledge Transfer and Science Transfer

Knowledge Transfer and Science Transfer  Metropolises

Metropolises  Maimed youths in the Congo, about 1904

Maimed youths in the Congo, about 1904  Mental Maps

Mental Maps  Migration from the Colonies

Migration from the Colonies  Model America

Model America  Model Classical Antiquity

Model Classical Antiquity  Modernization

Modernization  Oriental Despotism

Oriental Despotism  Outline of Batavia 1629

Outline of Batavia 1629  Pan-Ideologies

Pan-Ideologies  Postcolonial Studies

Postcolonial Studies  Europeanization

Europeanization  Reich

Reich  Russia and Europe (1547–1917)

Russia and Europe (1547–1917)  South Sea Bubble

South Sea Bubble  Yellow Peril

Yellow Peril  Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars

Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars  World War II

World War II  The Trial of Warren Hastings 1789

The Trial of Warren Hastings 1789  Trade and Economy*

Trade and Economy*  Translation

Translation  Women's Movements

Women's Movements  "Columbus taking possession of the new country" 1893

"Columbus taking possession of the new country" 1893 ![Image]() "Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorim of Calicut", ca. 1905 IMG

"Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorim of Calicut", ca. 1905 IMG  "Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorin of Calicut", c. 1905

"Vasco da Gama delivers the letter of King Manuel of Portugal to the Samorin of Calicut", c. 1905  Abendland

Abendland  Abolitionism in the Atlantic World

Abolitionism in the Atlantic World  Albert Sarraut (1872-1962)

Albert Sarraut (1872-1962) ![Image]() Albert Sarraut (1872-1962) IMG

Albert Sarraut (1872-1962) IMG  Battle in the Second Boer War 1899

Battle in the Second Boer War 1899 ![Image]() Carl Peters (1856-1918) IMG

Carl Peters (1856-1918) IMG  Carl Peters (1856–1918)

Carl Peters (1856–1918)  Christian Mission

Christian Mission  Colonialism and Imperialism

Colonialism and Imperialism  Decolonization and Revolution

Decolonization and Revolution  East India Companies*

East India Companies* ![Image]() Englische Karikatur zum indischen Aufstand 1857 IMG

Englische Karikatur zum indischen Aufstand 1857 IMG  English Cartoon on the Indian Rebellion of 1857

English Cartoon on the Indian Rebellion of 1857  Enlightenment Philosophy

Enlightenment Philosophy  European Encounters

European Encounters  European Overseas Rule

European Overseas Rule  Free Trade

Free Trade  Globalization

Globalization ![Image]() Grundriss von Batavia, 1629 IMG

Grundriss von Batavia, 1629 IMG  Herero Prisoners of War in German Southwest Africa 1904

Herero Prisoners of War in German Southwest Africa 1904 ![Image]() Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) IMG

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803) IMG  Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)

Johann Gottfried Herder (1744–1803)  John Trumbull (1756–1843), Declaration of Independence 1818

John Trumbull (1756–1843), Declaration of Independence 1818 ![Image]() John Trumbull (1756–1843), Declaration of Independence 1818 IMG

John Trumbull (1756–1843), Declaration of Independence 1818 IMG ![Image]() Kriegsgefangene Herero in Deutsch-Südwest-Afrika 1904 IMG

Kriegsgefangene Herero in Deutsch-Südwest-Afrika 1904 IMG  Maimed youths in the Congo, about 1904

Maimed youths in the Congo, about 1904  Outline of Batavia 1629

Outline of Batavia 1629 ![Image]() Prozess gegen Warren Hastings 1789 IMG

Prozess gegen Warren Hastings 1789 IMG  Racism

Racism ![Image]() Schlacht im Zweiten Burenkrieg 1899 IMG

Schlacht im Zweiten Burenkrieg 1899 IMG ![Image]() Schulwandbild "Columbus taking possession of the new country" 1893 IMG

Schulwandbild "Columbus taking possession of the new country" 1893 IMG  Siedlerkolonien

Siedlerkolonien  Slave Trade*

Slave Trade*  American Revolution

American Revolution  The Trial of Warren Hastings 1789

The Trial of Warren Hastings 1789 ![Image]() Verstümmelte Jugendliche im Kongo ca. 1904 IMG

Verstümmelte Jugendliche im Kongo ca. 1904 IMG ![Image]() Vertrag von Tordesillas IMG

Vertrag von Tordesillas IMG

Indices

http://ieg-ego.eu/en/threads/backgrounds/colonialism-and-imperialism/benedikt-stuchtey-colonialism-and-imperialism-1450-1950

---------------------

The myth of the 1,400 year Sunni-Shia war

The 'Sunni-Shia conflict' narrative is misguided at best and disingenuous at worst, suggests author.

![The myth of the 1,400 year Sunni-Shia war In Bahrain (circa March 2011), both Shia and Sunni opposition leaders come together, holding a sign reading "No Sunni, No Shia: One unified nation." [AP]](http://www.aljazeera.com/mritems/imagecache/mbdxxlarge/mritems/images/2013/7/9//201379101814745734_20.jpg)

By

Murtaza Hussain

Murtaza Hussain is a Toronto-based writer and analyst focused on issues related to Middle Eastern politics.Story highlights

During the period of European rule over Rwanda, the Belgian colonial administrators of the territory accomplished an extraordinary feat in their subjugation of the local population - the deliberate manufacture of new ethnic divisions.By formulating ethnic categorisations based on subjective judgments of Rwandans' height and skin colour, the Belgians sought to keep the Rwandan people at odds with one another and subservient to them. Entirely fabricated histories and genealogies were concocted for the "Hutu" and "Tutsi" peoples, although these terms themselves had been taken from the dustbin of Rwandan history and had had little effective meaning for hundreds of years.

This strategy of divide-and-conquer eventually resulted in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, a bloodbath which shocked the conscience of the world and claimed the lives of roughly

By formulating ethnic categorisations based on subjective judgments of Rwandans' height and skin colour, the Belgians sought to keep the Rwandan people at odds with one another and subservient to them. Entirely fabricated histories and genealogies were concocted for the "Hutu" and "Tutsi" peoples, although these terms themselves had been taken from the dustbin of Rwandan history and had had little effective meaning for hundreds of years.

This strategy of divide-and-conquer eventually resulted in the 1994 Rwandan Genocide, a bloodbath which shocked the conscience of the world and claimed the lives of roughly 800,000 people. Hutus and Tutsis, themselves only recently fabricated identities, had come to believe in a false narrative in which they had been in opposition to one another since the dawn of time.

Today it is increasingly common to hear talk of the existence of a "1,400 Year War" between Sunni and Shia Muslims. In this narrative, the sectarian violence of today is simply the continuation of an ancient religious conflict rooted in events which transpired in the 7th century. While some Muslims themselves have recently bought into this worldview, it would suffice to say that such beliefs represent not only a misreading of history but a complete and utter fabrication of it. While there are distinct theological differences between Sunnis and Shias, the claim that these two groups have been in a perpetual state of war and animosity throughout their existence is an absurd falsehood.

The conflict now brewing between certain Sunni and Shia political factions in the Middle East today has little or nothing to do with religious differences and everything to do with modern identity politics. Just as in Rwanda, Western powers and their local allies have sought to exacerbate these false divisions in order to perpetuate conflict and maintain a Middle East which is at once thoroughly divided and incapable of asserting itself.

False continuities

Analyses of the roots of sectarian conflict in the Middle East tend to look at the historical schism between Sunnis and Shias as the original driving factor behind present-day tensions. In this reading of events, the 680AD Battle of Karbala in which the descendants of the Prophet Muhammad (who are particularly revered by Shia Muslims) were killed was merely the first battle in a long and continuous sectarian conflict which today is being played out in Syria, Lebanon and other countries throughout the Middle East.

| Head to Head - What is wrong with Islam today? |

Indeed, while modern political factions often make reference to theological differences, the usage of symbolism and rhetoric which draws upon the distant past (a tactic employed by political opportunists around the world) is very different than the existence of an actual continuity between ancient history and the present. However, thanks to the efforts of well-funded religious demagogues - themselves either ignorant of history or cynical manipulators of it - this patently ridiculous explanation of world events is gaining some purchase even among Muslims themselves.

Remembering history in the Middle East

For those who would seek to shamelessly fabricate a historical narrative in order to serve their venal political interests, it is worth restating some basic realities about the nature of sectarian relationships in the Middle East. While over a millennium of cohabitation the various religious communities of the region have experienced identifiable ups-and-downs in their relations, the overall narrative between them is vastly more of pluralism, tolerance and accommodation than of hard-wired conflict and animosity.

For centuries, Sunnis and Shias (as well as Christians, Jews and other religious groups) have lived closely intertwined with one another to a degree without parallel elsewhere in the world. Even where they have exerted power through distinct political structures, the argument that this has equated to conflict does not stand up to even a cursory analysis. While the Sunni Ottoman Empire and Shia Safavid Empire experienced their share of conflict, they also lived peaceably alongside one another for hundreds of years, even considering it shameful to engage in conflict with one another as Muslim powers.

Furthermore, despite seething protestations to the contrary from zealots of all types, "sects" have hardly been separately self-contained entities over history. Shia and Sunni Muslim scholars have long engaged in dialogue and influenced the religious thought of one another for centuries, blurring the already largely superficial distinctions between the two communities. As a legacy of this, today the greatest seat of learning in Sunni Islam also teaches Shia theology as an integrated school of thought.

Modern Dark Ages

The contrast between this history and the unconscionably brutal wars of religion which for centuries ravaged Europe could not be starker. When describing tensions between factions in the Middle East today, Western analysts (and increasingly, many Muslims) tend to view events through a historical lens which is derived from a distinctly Western experience of intractable religious conflict. Indeed, far from being ancient history, Europe's dark obsession with religious hatred reached its nadir mere decades ago in the form of the Holocaust - perhaps the ultimate religious "pogrom" against the long-oppressed Jewish population of the continent.

| For every sectarian terrorist group or militia, there are countless ordinary Shia and Sunni Muslims around the world who have risked their lives to protect their co-religionists. |

While contemporary Muslim societies have regressed to the point where Europeans can now claim moral authority to lecture them on religious diversity, looking at history it should be noted that the periods of greatest religious tolerance within Islam have historically corresponded with the peaks of political power among Muslim empires. The lesson contained herein is something which modern leaders and religious figures - many of whom are disdainful at best towards minorities - ignore at their great peril.

A dangerous myth

Those who ignorantly claim that progress can be attained through the enforcement of strict ideological purity should take heed of the past and resist the temptation towards religious chauvinism. The conflict which some claim exists today between Sunni and Shia Muslims is a product of very recent global events; blowback from the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the petro-dollar fuelled global rise of Wahhabi reactionaries. It is decidedly not the continuation of any "1,400 year war" between Sunnis and Shias but is driven instead by the very modern phenomena of identity politics. Factions on both sides have created false histories for their own political benefit and have manufactured symbols and rituals which draw upon ancient history but are in fact entirely modern creations. Furthermore, Western military powers have sought to amplify these divisions to generate internecine conflicts within Muslim societies and engineer a bloodbath which will be to their own benefit.

While neoconservatives practically salivate in anticipation of Muslims committing mass-fratricide against one another, away from the political sphere ordinary people continue to live with the deeply engrained sense of tolerance that has traditionally characterised the once-global civilisation of Islam. For every sectarian terrorist group or militia, there are countless ordinary Shia and Sunni Muslims around the world who have risked their lives to protect their co-religionists as well as the religious minorities within their societies. For every story which discards the nuances of todays' conflicts and casts them as part of a narrative of spiralling sectarian violence, there are others which point resolutely in the opposite direction. In the words of an 80-year old Pakistani farmer, a man older than his own country: "I've witnessed this Shia-Sunni brotherhood from my childhood, you can say from the day I was born."

In Rwanda a people who came to believe a false history about themselves ended up being driven towards madness and self-destruction. Today, the Rwandan government has done away with the artificial colonial categorisations of "Hutu" and "Tutsi" and has formally recognised all Rwandan citizens as being of one ethnicity. Similarly, it is incumbent upon Muslims to reject crude myths about a 1,400 year sectarian war between themselves and to recognise the dangerous folly of such beliefs.

Indeed, the simple truth is that if such a war existed Sunnis and Shias would not have been intermarrying and living in the same neighbourhoods up to the 21st century. Furthermore, were they truly enemies, millions of people of both sects would have stopped peacefully converging on the annual Hajj pilgrimage many centuries ago. If Islam is to continue as a constructive social phenomenon it is important that these traditional relationships and ways of life are not destroyed by modern ideologies masquerading as historical truths.

Murtaza Hussain is a Toronto-based writer and analyst focused on issues related to Middle Eastern politics.

Follow him on Twitter: @MazMHussain

http://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2013/07/2013719220768151.html

------------------------

-----------------

French, Spanish, and English Colonization

The French, Spanish, and English all tried to colonize the Western Hemisphere. The French colonization in America started in the 16th century, and continued through centuries as France created an empire in the Western Hemisphere. They founded most colonies in the east of the U.S.A, and many Caribbean islands. The English were one of the most important colonizers of the Americas, and really had a rivalry against the Spanish. The English began colonizing in the late 16th century and came out on top when all their colonies were built through America. The Spanish really conquered most of the Western Hemisphere, their colonization attempts were started by the Spanish conquistadors, It went from Christopher Columbus arriving in America in 1492 and went on for nearly four centuries when the Spanish Empire expanded in most of present day Central America.

The English reached it’s peak of gaining land through colonization in the late 16th century, they established many colonies throughout the Americas, they were very important colonizers of Americas, and had advances in military and economic features, though they were rivals with Spanish colonies. Even with their success, the English had their problems, their colonization attempts caused a lot of problems to civilizations in America, with their military, they caused cultural disruption, and they introduced many diseases throughout every colony. The English had the most advances in their war strategies with their long history of warfare, just like the Spanish. The French, English, and Spanish have something in common; trade was a huge part in their colonial policies, although the English promoted settlement and development more than the French and Spanish.

Though the French didn’t have the best military, they were very rich in the trading business. Most of the colonies they colonized were able to export products such as fish, sugar and furs. The French established forts and settlements that are now present day...

The English reached it’s peak of gaining land through colonization in the late 16th century, they established many colonies throughout the Americas, they were very important colonizers of Americas, and had advances in military and economic features, though they were rivals with Spanish colonies. Even with their success, the English had their problems, their colonization attempts caused a lot of problems to civilizations in America, with their military, they caused cultural disruption, and they introduced many diseases throughout every colony. The English had the most advances in their war strategies with their long history of warfare, just like the Spanish. The French, English, and Spanish have something in common; trade was a huge part in their colonial policies, although the English promoted settlement and development more than the French and Spanish.

Though the French didn’t have the best military, they were very rich in the trading business. Most of the colonies they colonized were able to export products such as fish, sugar and furs. The French established forts and settlements that are now present day...

-----------------

U.S. Foreign Policy Failures - Alternative Insight

After World War II, United States foreign policy often failed to accomplish its ... Interference in internal affairs of nations and direct American military ... African Scene .... and will counter attempts that undermine its economic activities in the Middle East. ... Russia Tests Its Nuclear Deterrent as NATO's Missile Defense Shi...

The revolt against the West: intervention and sovereignty: Third ...

The 2011 NATO military intervention in Libya did potentially irreparable damage to ... Keywords: United Nations, sovereignty, intervention, decolonisation, ... Between 1945 and 1960, 40 Asian and African countries with populations of some .... Only 12 Asian (including Middle Eastern) and African states (out of 48) were thus ...

History of U.S. Military Interventions since 1890

... 1982), "Instances of Use of United States Forces Abroad, ...

Outline of American History - Chapter 11: Postwar America

In the 1950s, African Americans launched a crusade, joined later by other minority groups and ... In the 1960s, politically active students protested the nation's role abroad, .... "I believe that it must be the policy of the United States to support free peoples who are .... Cold War struggles were also occurring in the Middl...

United States Military Involvement facts, information, pictures ...

Get information, facts, and pictures about United States Military Involvement at Encyclopedia.com. ... In the middle of the nineteenth century, adventurers or “ filibusters” like ... Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, and the United Nations. ... which, like the 1949 North Atlantic Treaty (NATO), declared an attack against one ...

foreign aid facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles ...

The United States government first recognized the usefulness of foreign aid as a ... have experienced great advances in their standard of living since the 1960s. ... billion in military and economic assistance to the Middle East and South Asia, .... Russia and America vying for influence over the newly formed nation-states of ...

The Warsaw Pact

The Warsaw Pact alliance of the East European socialist states is the nominal counterweight .... In an effort to derail the admission of West Germany to NATO, the Soviet ... aggression, as provided for in Article 51 of the United Nations Charter. ... Until the early 1960s, the Soviet Union used the Warsaw Pact more as a tool in .....

--------------

U.S. Foreign Policy Failures - Alternative Insight

After World War II, United States foreign policy often failed to accomplish its ... Interference in internal affairs of nations and direct American military ... African Scene .... and will counter attempts that undermine its economic activities in the Middle East. ... Russia Tests Its Nuclear Deterrent as NATO's Missile Defense Shi...

----------------

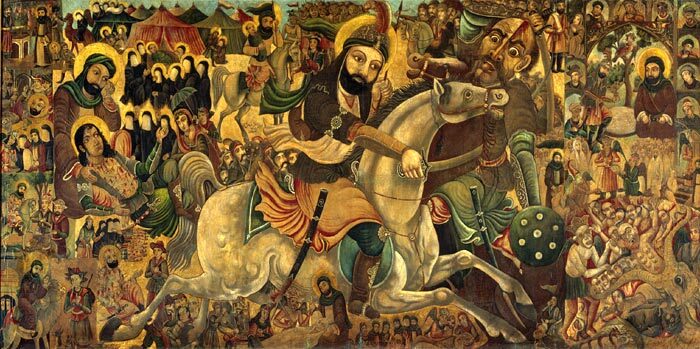

Chronology: A History of the Shiite-Sunni Split

A painting depicts the battle of Karbala in 680, in which Imam Hussein engaged a superior Arab army and was killed in battle. Brooklyn Museum/Corbis hide caption

toggle caption

A painting depicts the battle of Karbala in 680, in which Imam Hussein engaged a superior Arab army and was killed in battle.

Brooklyn Museum/Corbis More About the Series

Series Overview: The Partisans of Ali Feb. 12, 2007

Profiles: Key Individuals in the Shiite-Sunni Divide Feb. 12, 2007

One Thousand Years of Shiite History Feb. 9, 2007

Suggested Reading: The Shiite-Sunni Conflict Feb. 12, 2007

570: The Prophet Muhammad is born.

598: Ali, who will become the fourth caliph and the first Shiite Imam, is born.

610: The year Muslims cite as the beginning of Muhammad's mission and revelation of the Quran.

613: The public preaching of Islam begins.

630: The Muslims, led by Muhammad, conquer Mecca.

632: Muhammad dies. Abu Bakr is chosen as caliph, his successor. A minority favors Ali. They become known as Shiat Ali, or the partisans of Ali.

656: Ali becomes the fourth caliph after his predecessor is assassinated. Some among the Muslims rebel against him.

661: Violence and turmoil spread among the Muslims; Ali is assassinated.

680: Hussein, son of Ali, marches against the superior army of the caliph at Karbala in Iraq. He is defeated, his army massacred, and he is beheaded. The split between Shiites and Sunnis deepens. Shiites consider Ali their first imam, Hussein the third.

Article continues after sponsorship

873: The 11th Shiite Imam dies. No one succeeds him.

873-940: In the period, known as the Lesser Occultation, the son of the 11th Imam disappears, leaving his representatives to head the Shiite faith.

940: The Greater Occultation of the 12th or Hidden Imam begins. No imam or representative presides over the Shiite faithful.

1258: The Mongols, led by Hulagu, destroy Baghdad, ending the Sunni Arab caliphate.

1501: Ismail I establishes the Safavid dynasty in Persia and declares Shiism the state religion.

1900: Ruhollah Khomeini is born in Persia.

1920-1922: Arabs, both Shiite and Sunni, revolt against British control of Iraq.

1922-1924: Kemal Ataturk abolishes the Ottoman sultanate and the Turkish Sunni caliphate.

1925: Reza Khan seizes power in Persia, declares himself shah, establishing the Pahlavi dynasty.

1932: Iraq becomes an independent nation, under King Faisal, a Sunni Arab.

1935: Persia is renamed Iran.

1941: Reza Shah abdicates throne in favor of his son Mohammad Reza Shah. British and Soviet military forces occupy Iran.

1953: A joint CIA/British intelligence operation in Iran keeps the shah on the throne and ousts nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh.

1963: Amid widespread protests in Iran against the shah, Ayatollah Khomeini is arrested, then exiled to Najaf in Iraq.

1967: Israel defeats Egypt, Syria and Jordan in the Six-Day War.

1968: The Baath Party seizes power in Iraq.

1973: Israel defeats Egypt and Syria in the Yom Kippur War.

1978-79: Widespread protests force the shah to abdicate and flee Iran. Ayatollah Khomeini returns to Iran to lead the revolution.

1979: Saddam Hussein seizes power, becomes president of Iraq. Iranian revolutionary students seize the U.S. Embassy in Tehran and take diplomats hostage. They are released in January 1981.

1980: Saddam orders the Iraqi army to attack Iran.

1980-1988: Iran-Iraq War. Hundreds of thousands die on each side and the war ends in a stalemate.

1982: Israel invades Lebanon, seizes Beirut. Hezbollah is formed in Lebanon.

1983: Suicide truck bombers, believed to be Hezbollah, kill 241 American servicemen in Beirut.

1989: Ayatollah Khomeini dies in Iran.

1990: Saddam orders his army to seize Kuwait.

1991: The U.S. military ousts the Iraqi army from Kuwait. Shiites of southern Iraq rebel against Saddam, who puts down the rebellion brutally. Thousands of Shiites are killed.

1991-2003: Iraq is placed under economic sanctions. U.N. weapons inspectors destroy most of Iraq's nuclear, biological and chemical weapons programs.

2001: Al-Qaida, led by Sunni Muslim fundamentalists, mounts attacks in the United States, killing 3,000 people. The United States invades Afghanistan and ousts the Sunni Taliban government.

2003: The U.S. military invades Iraq, topples Saddam. An Iraqi insurgency erupts, led by Sunni Baathists and al-Qaida.

2005-2006: Iraqi elections bring Shiite political parties to power in Baghdad, backed by Iran. Sunni-Shiite sectarian violence intensifies.

2005: Hard-line fundamentalist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad is elected president in Iran. Iran pursues acquisition of nuclear technology.

2006: War breaks out between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon. The U.N. Security Council imposes economic sanctions on Iran in response to nuclear activities.

2007: The United States sends additional troops to Iraq.

http://www.npr.org/2007/02/12/7280905/chronology-a-history-of-the-shia-sunni-split

-----------------------

Sunni vs Shiite: A Cold War Simmers in an Ancient Hatred

Amb.

Zvi Mazel 10 Jan 2016

·

·

The

roots of the crisis are to be found in the long-standing feud between Sunni and

Shiite, which dates from the very beginning of Islam.

The

execution of Nimr al-Nimr, a Shiite cleric and bitter opponent of the Saudi

regime who regularly and publicly insulted the royal family, has triggered an

unprecedented crisis between Tehran and Riyadh.

Nimr al-Nimr, opponent of Saudi Arabia

King Salman of Saudi Arabia

Though it was not totally unexpected given the present

geopolitical turmoil in the Middle East, the roots of the crisis are to be

found in the long-standing feud between Sunni and Shiite, which dates from the

very beginning of Islam.

The Prophet Mohammad wanted all Arab tribes to remain

united, but the battle for his successor left Islam torn between Sunni and

Shiite, though both believe in the prophet and in the Koran and aspire to

impose the rule of Islam on the entire world. Each developed their own

narrative and their own ethos, which leaves no room for compromise or

reconciliation.

Following historical ups and downs, Sunni Islam, with

Saudi Arabia as its leader, today accounts for 85 percent of all Muslims while

Shiite Islam, spearheaded by Iran, musters the remaining 15 percent.

The Sunni block, however, is no longer monolithic.

There are a number of radical organizations – from

al-Qaida to Islamic State and some 40 smaller groups – aiming to use force to

restore the caliphate through jihad. They are generally lumped under the name

of Islamist or jihadist radical Islamic organizations. Like main stream Sunnis,

their teachings are based on the Shari’a, perhaps professing stricter

observation.

Meanwhile, in Iran, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who

came to power in 1979, launched a new drive to impose Shiite Islam on the whole

Middle East as a first step to be followed by a world takeover. He called on

Shiite minorities in Sunni states to act against these states to destabilize

them from within and eventually topple them and set up a Shiite regime in their

stead, thereby securing Iran’s position as regional power.

Syria, ruled by the Alawites and hitherto shunned by

mainstream Sunni, was given legitimacy by the Ayatollahs and became Teheran’s

willing ally.

Building on the frustrations of the Shiite in Lebanon,

which complained of discrimination, Iran set up the Hizbullah with a

three-pronged objective: taking over the country, threatening Israel and

developing subversive activities in Jordan and Egypt.

In 2008, Egyptian authorities exposed a Hizbullah cell

that planned an attack on the Suez Canal; today Hizbullah fighters are helping

Assad in Syria at Tehran’s bidding.

In the Gulf, Saudi Arabia is the main bulwark of Sunni

Islam against Iran’s subversive activities and, as such, is considered that

country’s arch-enemy.

The kingdom has a number of unassailable assets. Both

of Islam’s holiest sites – Mecca and Medina – are situated in its territory; it

has the largest oil reserves in the world, and it is – or was – both friend and

ally of the United States.

Iran Incites Shiites in the Arabian

Peninsula

Once again, Tehran resorted to subversion, inciting

Shiite minorities in the area. Iran did not hesitate to proclaim that Bahrain,

where there is a Shiite majority though the country, as Iran’s 14th province

despite the fact that Bahrain is ruled by the Sunni Al Khalifa family. Egypt’s

then-president Hosni Mubarak rushed to Bahrain’s capital Manama to demonstrate

to the Iranians that security in the Gulf was an essential component of

Egyptian national security.

In 2011, soon after Mubarak was ousted during the

so-called Arab Spring, violent manifestations threatened to topple the regime

in Bahrain, as well. Saudi Arabia and other Emirate countries sent troops to

help quell the revolt.

There is a significant Shiite minority in Saudi

Arabia, mainly in the eastern part of the country where the largest oil fields

are situated, and Iran spared no efforts to enlist the Shiites’ support. Nimr

al-Nimr was its firebrand leader and, as such, was jailed a number of times.

In 2012, al-Nimr fomented several demonstrations

against the regime, was jailed again and sentenced to death for rebellion under

the strict Shari’a laws backed by a number of verses of the Koran. His

execution was intended as a wakeup call to the Sunni states and as a warning to

the Shiite minority and to Iran: henceforth Riyadh would no longer tolerate

Iranian subversive activities and threatening declarations against the kingdom

and its Emirate allies.

Iran’s threats are taken seriously in view of Iran’s

actions in recent years – open intervention in Syria through its proxy

Hizbullah to help Assad; furthering its influence in Iraq by reinforcing Shiite

political parties but also by setting up Shiite militias to replace the

country’s army, which failed dismally in its fight against Islamic State.

Then came the last straw.

Tehran spurred on Houthi rebels in Yemen, Saudi

Arabia’s southern neighbor which commands the entrance to the Red Sea and the

Suez Canal, supplying the Houthis with weapons and ammunition. The Saudis felt

they were surrounded.

If the situation were not dire enough for the

embattled kingdom, the perceived desertion of the United States, its staunchest

ally for decades, left it with no option but to take a stand.

Under the leadership of President Barack Obama, secret

talks had been held with Iran, leading to an agreement purportedly delaying the

manufacture of nuclear weapons by a number of years but not addressing the

country’s terrorist actions against neighboring states – a move seen in the

Middle East as de facto recognition by Washington of Iran’s and Shiite

hegemony.

Battle lines are drawn.

Saudi Arabia – which unlike Tehran is taking part in

the American led coalition against Islamic State has set up a coalition of its

own to fight the Houthis in Yemen.

In December, it launched another coalition – Islamic

countries against the Islamic State.

It is making an all-out effort to help Egypt’s

economy. Under Mubarak, Cairo was at the forefront of the fight against Iran’s

attempts at hegemony.

And What of the United States?

Here, too, America has more or less turned its back on

its former great ally, Egypt. Cairo is shifting its stand toward Russia, which

supports Assad. A minor problem Egyptian and Saudi leaders are doing their best

to ignore.

What now? Saudi Arabia has broken off ties with

Tehran, followed by Bahrain, Sudan and Djibouti – two countries that have

suffered greatly from Iranian subversive activities.

The United Arab Emirates downgraded their ties. Kuwait

and Qatar recalled their ambassadors. Sunni countries are temporarily setting

aside their quarrels and interests to face the common Shiite enemy. An urgent

meeting of the Arab League will be convened this week.

And what of the United States? It is asking both sides

for restraint, which is rather meaningless, especially considering that it was

because it sided with Tehran and weakened its erstwhile allies that the present

situation has developed.

Russia is also offering its good offices to defuse the

crisis. This is another success for Putin, who is asserting his country’s

greater influence in the Middle East.

It seems that Tehran, embroiled in fighting Islamic

State and in sustaining Bashar Assad’s regime, has no wish to add fuel to the

fire. So-called moderate voices in Iran openly accuse the regime of having

overreacted in letting frenzied mobs loose on Saudi representations.

The present crisis may end in a suitable compromise –

but the age-old enmity between Sunni and Shiite remains stronger than ever.

----------

Who Will Win the Middle East?

Since

the middle of the twentieth century, the Middle East has seen regional

hegemons come and go. The 1950s and 1960s were Egypt’s era: Cairo was

the Arab World’s capital and the home of its charismatic postcolonial

leader, Gamal Abdel Nasser. But Israel’s victory over Egypt, Jordan, and

Syria in the 1967 war; Nasser’s death, in 1970; and the spike in oil

prices after the 1973 war brought that era to an end. As millions of

Egyptians and other Arabs left home for the oil-wealthy Gulf, the

gravity of Arab politics went with them. As the Gulf’s fortunes rose,

especially in Saudi Arabia, so too did Riyadh’s political clout. Iraqi

leader Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, however, and the

subsequent U.S.-led war, which was launched from Saudi soil, made clear

that oil could buy Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia, a lot of

influence, but they still needed American protection.

After the Gulf War, in the first half of the 1990s, the Oslo Agreement between the Israelis and the Palestinians and the Israeli-Jordanian Peace Treaty, shepherded by Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin, gave rise to Israel’s moment in the Middle East. Regional economic cooperation took center stage, casting the politics of the previous four decades aside with the optimism of peace and integration. Rabin’s assassination in 1995 abruptly dashed those hopes. The peace process floundered by the end of the decade, as a new rightwing in Israeli politics rose to power, hardly disposed to any closeness to its neighbors.

Then there was a void; the 2000s was no one’s decade. No Arab country had the power, resources, or credibility to assert itself across the whole region. Sectarianism spread, fuelled by the U.S. occupation of Iraq and ensuing civil war. Arab republics, such as Egypt, Syria, and Tunisia, witnessed shocking levels of corruption that eroded the foundation upon which they were built in the 1950s: social equality and the consent of the lower middle classes to the reigning regimes. In the Gulf, the ruling dynasties sought to turn their desert towns into glittering cities, modeled on Hong Kong and Singapore, and detached themselves from the problems of their other Arab neighbors. Whereas in previous decades the region’s strategic landscape had depended on one country’s ascendancy, by 2011, with so much of the region muddling through and failing to put together serious national or regional political projects, the dominant players in the Middle East seemed to be economic actors, from multinational corporations to regional financial interests.

The Arab uprisings of the last three years shook up the balance of power once more, toppling three of the Arab republics, Egypt, Libya, and Tunisia; threatening Arab monarchies in the Gulf; and sewing chaos around Israel. Whereas most observers evaluate the uprisings in terms of the political changes they did -- or did not -- usher in, there are other forces at play. A larger power struggle has emerged out of the ashes of revolution, repression, and war from Tunisia to Syria, which is reshaping the entire strategic landscape of the Middle East. Its outcome will transform the entire region more than any regional rivalry or the rise or fall of any single power in the preceding half century.

FACE OFF

At the heart of this transformation are two groups of countries and political forces with opposing objectives. The first, led by Islamist forces in Iran, Qatar, Turkey, and the large Arab political Islamist groups such as the Muslim Brotherhood, aims to channel the energy of the Arab uprisings toward a gradual Islamization of the region. The definition of that Islamization varies depending on the ideologies, backgrounds, and social and political circumstances of each country. The camp’s unifying conviction, however, is that political Islam is the sole framework for governing. Its members believe that, unlike the old rhetoric of secular Arab nationalism or republicanism, Islamism can actually win the support of the widest social segments in the region -- and keep it. To promote its goals, the camp uses a loosely organized network of media, religious authorities, and financial interests to rouse wide sections of the more than 180 million Arabs who are under 35 years old to demand bottom-up change.

The other camp, led by Saudi Arabia and other Gulf monarchies, such as Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates, and supported by Egypt, Israel, and Jordan, sees this transformation as a threat. They -- the traditionalists -- believe that Islamization will bring further fragmentation in some countries, such as Iraq, Lebanon, and Syria; highly disruptive political and social discord in others, such as Egypt; and the strengthening of jihadist groups across the region. Favoring a more gradual, managed, and cautious evolution of the existing order, the traditionalist camp relies on militaries, security apparatuses, media and financial interests, and other state or state-backed institutions to enforce a message of national preservation and shield their countries from the upheaval unfolding across the region.

The battle between the two groups is a new kind of fight in the Middle East. Previous struggles between Arab secularists and Islamists (for example, between Nasser and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood in the 1950s, or between the Assad regime and the Brotherhood in the late 1970s and early 1980s) were country and regime specific. The Arab-Israeli conflict, meanwhile, has been primarily over territories. And the contest between secular Arab republics and Gulf monarchies throughout the 1960s (such as between Nasser’s Egypt and Saudi Arabia) revolved around the survival of specific regimes. This emerging two-camp confrontation, however, is over the nature and future of the region’s societies, from North Africa to the Gulf.

TROUBLE IN EVERY DIRECTION

The struggle between these two camps will be determined by four factors. The first is Egypt’s future. With nearly 90 million people, the country is the home of a third of all Arabs and, for decades, has been the region’s cultural trendsetter. Political Islam has already shaped Egypt’s politics since the fall of President Mubarak, throughout President Mohamed Morsi’s year in office, and, since Morsi’s ouster last summer, in the ongoing struggle between the resurgent nationalists -- and at their core, the military establishment -- and the Islamists. But it is really Egypt’s economy that will determine the country’s course. If Egypt’s government, likely led by Field Marshal Abdel Fattah El-Sisi, who is widely expected to win a May 25–26 presidential election, can finally put forward badly needed economic reforms, including cutting back on unaffordable public subsidies, without losing popular support and risking another round of political protest, then Egypt could regain its status as a player in the region and significantly bolster the second camp. But that is a tall order. And if it fails, another round of unrest would doom the traditionalists’ camp.

The second variable is the future of Algeria, North Africa’s largest and richest country, thanks in large part to its oil and gas wealth. (Algeria is Europe’s third-largest energy supplier.) The military regime has been buying time until it can find a replacement for the ailing, aged President Abdelaziz Bouteflika. His replacement must be acceptable to the generals who have controlled the country for over four decades and be conciliatory to the political Islamists that fought the regime throughout the 1990s in a war that cost 100,000 lives. The regime still survives by buying off such dissenters and playing off the public’s fear of returning to the violence of the 1990s, which compels many Algerians to accept the lack of plurality in return for peace and stability. But although the Algerian regime survived the wave of protests in 2011 intact, it is hardly bulletproof. Algerian political Islam has evolved beyond its 1990s antagonistic worldview. New Algerian Islamist parties could reemerge as a serious rival to the military regime. And with Algeria’s immense financial resources, this would give the first camp a major strategic advantage.

The third factor is Saudi Arabia, where the royal family is digging in its heels. A rising middle class that has a huge stake in the economy -- and has been increasingly exposed to political and social currents outside the conservative kingdom -- has finally started to demand political representation. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s economic prospects are slowly deteriorating. (The country is expected to become a net energy importer by 2030.) A sagging economy will only hinder the royal family’s ability to keep buying middle-class support through social welfare and public allowances. The threats of a low-level Shiite insurgency in the kingdom’s eastern province, a renewed Shiite Houthi militancy on the borders with Yemen, or a protest movement among young, disaffected Saudis could erode the government’s authority. A weakening of the Saudi regime would undermine the traditionalists’ camp by diverting the resources and dampening the will of its most powerful and assertive member.

But there is another scenario. King Abdullah, who is 89 years old, has shuffled responsibilities and positions within the ruling family, and the rising (relatively young) princes are aware of the challenges their political system faces. If, motivated by these existential threats, the Saudi regime can evolve and turn the kingdom into a functioning constitutional monarchy in which the political, social, and economic rights of large groups of young Saudis are respected, it could lead to a long but relatively stable transition. A new, assertive Saudi leadership, buoyed by political legitimacy, would imbue the traditionalists’ camp with strong momentum.

The fourth factor is just how much more chaos the Middle East sees over the coming decade. The civil war in Syria is likely to end with a semblance of a centralized authority in Damascus, surrounded by quasi-independent political entities. Several Salafist jihadist groups in the country could manage to entrench themselves in the increasingly lawless desert plains extending from eastern Syria to western Iraq, where they could try to establish Islamic statelets, isolated from the surrounding world (as similar groups have tried in Afghanistan and the Caucasus). Their presence will be a source of violence and political fragility, primarily for Syria and Iraq, but also for Lebanon and Jordan, opening more fronts in the battle between the two camps.

The camp that can turn the political contests in the region to their advantage, by deflecting potential chaos and inflicting its consequences on the other camp, will be better positioned to win this strategic struggle.

THERE’S A STORM COMING