BLOGGED:

Canada Military News: Queen

Victoria's Order of Nurses - #MealsOnWheels - CANADA'S #VON - nursing without

walls-God's Angels Among Us- Your meals on wheels saves etc saves us

elderly/disabled throwaways - from Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia with love -

most trusted in the world.... thx u for loving the old, weary, broken and the

throwaways of society-ur truly God's Angels among us- and a hug out 2

#CanadianRedCross as well and #firstresponders

----------------------

There are three general reasons why Victoria Day and the Queen’s Birthday were, and are, so important in the Canadian calendar – their role in Canadian history; heritage and values; the Canadian climate; and the special nature of a holiday paying tribute to a real person

The key point that needs to be made is that these celebrations reflected not the ideas and tastes of the governments of the day but the ideas and tastes of the people. And that is why the Queen’s Birthday has always been celebrated in such diverse and ordinary ways, as well as grand ways, across the country. If one may paraphrase our republican neighbours to the south, the Queen’s Birthday is a holiday of the people, by the people and for the people and their Queen.

Statement

by the Prime Minister of Canada on the occasion of Victoria Day

May 18, 2015

Ottawa, Ontario

“Today, Laureen and I join Canadians from across the country to officially celebrate the birthday of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Canada.

“This year marks an historic moment of tremendous significance for both our Queen and country. On September 9, Her Majesty’s reign will officially surpass that of her great-great-grandmother, Queen Victoria, making her the longest reigning Sovereign in the modern era of our country. In the entire history of Canada, only the reign of King Louis XIV was longer at 72 years.

“For over 63 years, Her Majesty has served Canada and Canadians with wisdom, dignity and dedication. It is for this reason that later this year we will commemorate her historic reign in a variety of visible and meaningful ways, including the awarding of the first Canadian Queen Elizabeth II Diamond Jubilee Scholarship to students for international exchanges across the Commonwealth, the issuing of commemorative coins (Royal Canadian Mint), a stamp (Canada Post) and a $20 bank note (Bank of Canada). The Government of Canada will also broadly distribute a special edition of its educational booklet on the Canadian Crown – A Crown of Maples / La Couronne canadienne – including to individuals who become Canada’s newest citizens at citizenship court ceremonies.

“As we move closer to celebrating the 150th anniversary of Confederation in 2017, we are reminded of the many proud chapters of our history in which the Queen played a pivotal role, thus emphasizing the central role of the Crown in both the daily life and identity of our country.

“On this Victoria Day, let us reflect on Her Majesty’s enduring service based on a deep affection for and unwavering dedication to this country and all Canadians. We wish Her Majesty continued health and happiness in the years to come.”

-----------------

The Queen’s Birthday in Canada

by Garry Toffoli

“The Twenty-Fourth of May is the Queen’s Birthday.

If we don’t get a holiday, we’ll all run away.”

Many Canadians are familiar with that school yard jingle. It was certainly still in vogue in the 1950s and 1960s. It originated in the 19th Century with rumours that schools might not be closed for the holiday on the Queen’s Birthday. Monarchy is often claimed by its opponents to be the concern only of the elderly or the old fashioned. But there it was, Canada’s first student protest movement – formed to defend Canada’s royal heritage against the students’ elders. And it was a successful one at that – the students got their holiday! The memory of those young royal radicals was perpetuated throughout the 20th Century, when home fireworks were popular, with the ubiquitous “burning school house” being the highlight of the backyard display on Victoria Day.

Queen Victoria died in 1901. Why is Victoria Day still a hoiiday in Canada? A related question often asked is why do Canadians still celebrate Victoria Day when the people of the United Kingdom don’t anymore? The latter question, of course, betrays a colonial attitude in the mind of the asker. Why should Canadians even care if the British celebrate it or not in deciding what should be done in Canada. But the answer is even more emphatic.

The British no longer celebrate Victoria Day because they never did celebrate it. It is a uniquely Canadian holiday. The British do celebrate the Queen’s Official Birthday (i.e. Queen Elizabeth II’s) but the Canadian celebration of the Queen’s Official Birthday is also distinctly different from the British and is intimately tied up with Victoria Day.

There are three general reasons why Victoria Day and the Queen’s Birthday were, and are, so important in the Canadian calendar – their role in Canadian history; heritage and values; the Canadian climate; and the special nature of a holiday paying tribute to a real person.

First the history.

The Sovereign’s Birthday really began as a public celebration in London, England in 1785 when King George III, the first sovereign to reign over all of Canada, celebrated his birthday on 4th June with a Trooping the Colour ceremony by the Guards. The ceremony has been expanded, and the Household Cavalry was added in later years to the event, but the celebration has remained essentially the same in the United Kingdom ever since – that is a military one. The date has changed with different monarchs and Elizabeth II’s Official Birthday falls on a Saturday each year, usually the first or second in June. It is not a day off and there are few, if any, civic or public events as such other than the Trooping.

In Canada there was a different history. The King’s Birthday started with a military flavour as well. It was the occasion when the local militia, all the able-bodied men in a community, undertook their one day of compulsory training, if one could call it training. Basically they marched around for a couple of hours on the village square carrying their own muskets or rifles or pitchforks, then went for a beer at the local pub afterwards. The promotion of the Victoria Day weekend by a Canadian beer company in recent years as the “Two -Four” (a case of twenty-four bottles of beer) Weekend actually has historic roots therefore.

It was in the reigns of King George IV and King William IV that the idea of an “official” birthday emerged, as the two monarchs each decided to celebrate their birthdays from 1820 to 1837, not on the actual days they were born but on the day of their father, King George III’s, birthday (4th June), which had been the day of celebration for the six decades of that king’s long reign.

The observances were to change in Canada in Queen Victoria’s reign in a way that they never did in Britain.

Queen Victoria had a close relationship with Canada even though she never came here in person. Her father, Prince Edward, Duke of Kent, as a 23-year-old soldier, came to Canada to live in 1791 and stayed here until 1800, having risen to the position of Commander in Chief of British North America – one half of the position now held by the Governor General of Canada. Although the Duke died before Victoria was a year old, she knew the many Canadian friends of her father and was well aware of her Canadian heritage. She always took a special and personal interest in Canadian affairs, eventually sending all four of her sons and one of her daughters to visit, live in and work in Canada.- for example, Princess Louise as wife of the Governor General and the Duke of Connaught first as a soldier in his mother’s reign and later, returning in his nephew’s reign, as Governor General.

Queen Victoria came to the Throne in 1837. In 1840 the Province of Canada was created through the union of modern-day southern Ontario and southern Quebec. In 1845 the province, already feeling a special bond to the young Queen, made the Queen’s Birthday an official Canadian public holiday and it changed from a military event to a civilian one. It was still a relatively sedate celebration however. Then something happened.

The 1840s were a period of political turmoil which Canadians of the late 20th and early 21st centuries might not relate to – or perhaps they would. There was division between English and French, and battles over education – should there be separate schools, should the school systems be provincially controlled or locally controlled. A new populist political force, largely rural and western-based (the west in those days meant southwestern Ontario), had emerged to challenge the Toronto-Montreal eastern establishment. It was called the Reform Party. It eventually merged in an alliance with traditional eastern urban businessmen and became – the modern Liberal Party of Canada. And there was a separatist movement in the Quebec half of Canada. It was formed by Anglo-Montrealers who were upset by what they perceived as a pro-French bias in the government. In 1849 they burned down the parliament buildings, which were then in Montreal (and which is why they are not there now and why the capital of Canada ended up in Ottawa) and they issued the infamous Annexation Manifesto, calling for the separation of Canada from the British Empire and its annexation by the United States.

This was too much for the Anglo-Montrealers’ erstwhile allies and friends in English Ontario. Ontario conservatives formed the British America League, reaffirming loyalty to monarchical principles and the British Empire and advocating a different solution to the problems of Canada – a confederation of all the British provinces in North America. As part of this outpouring of loyalty and patriotism, the people of Toronto pulled out all the stops for the Queen’s Birthday and turned the next celebration into a day of demonstrating Canadian pride in their country and their Queen. Soon the Toronto-style celebration spread across the province and, after 1867, across the dominion.

The military parades were still an important part of the day, but there were public picnics and band concerts, sports events (the Queen’s Plate was originally run on the Queen’s Birthday), excursions, dinners, and eventually fireworks and the opening of cottages. And the Queen’s Birthday never looked back.

The key point that needs to be made is that these celebrations reflected not the ideas and tastes of the governments of the day but the ideas and tastes of the people. And that is why the Queen’s Birthday has always been celebrated in such diverse and ordinary ways, as well as grand ways, across the country. If one may paraphrase our republican neighbours to the south, the Queen’s Birthday is a holiday of the people, by the people and for the people and their Queen.

One could go out on a limb and say that Queen Victoria meant more to Canadians than she did to the British of the United Kingdom, because it was in Victoria’s reign that Canada was created and established its distinct identity. The idea thrown around carelessly today, that Canadians need to create their own identity, is nonsense. The did it well over a century ago and, as a result, Canada will always remain a Victorian country at heart, in the same way that the United States will always remain an 18th Century neo-classical country, because it was created in that era.

Victoria played an active role in Canadian development. For instance, she chose Ottawa as the new capital – the Westminster of the Wilderness, and named British Columbia, and she personally encouraged Confederation in 1867. But she was also the symbolic focus of Canadian unity. Sir John A. Macdonald, the Father of Confederation, said that the purpose of Confederation “was to declare in the most solemn and emphatic manner [Canadians'] resolve to be under the sovereignty of [Queen Victoria] and [her] family forever”. Victoria was truly the Mother of Confederation.

As a result, when Queen Victoria died in January 1901, the Canadian Parliament, independent of anything that was happening elsewhere in the Empire, created a memorial holiday “Victoria Day” on 24th May to remember the Queen’s birthday. That is the beginning of “Victoria Day” distinct from “The Queen’s Birthday” as a holiday. The new monarch, King Edward VII’s birthday was in November so Canadians decided to continue celebrating it officially on 24th May. King George V was born in June however so, in 1911, the King’s Birthday was celebrated in June and Victoria Day continued to be observed on 24th May. Except for two years, that remained the situation until Queen Elizabeth II came to the Throne in 1952.

1936 was the year of two King’s Birthdays in Canada. Canadians celebrated King Edward VIII’s official birthday on Victoria Day. But then he abdicated the Throne and his brother George VI became King on 11th December. The new King’s actual birthday, which was on 14th December, was also officially celebrated that year. The next year the official celebration was moved to June.

In 1939 King George VI and Queen Elizabeth came to Canada. The King was the first reigning monarch to do so. As part of that great tour the King’s Official Birthday in Canada was declared to be 20th May, when he was in Ottawa, and a Trooping the Colour was held on the lawn of Parliament Hill by the Canadian Brigade of Guards. It was the only year when a monarch had been in Canada for his or her official birthday until Queen Elizabeth II celebrated her official birthday in Edmonton on 22nd May, 2005.

In 1952 the official birthday of the new monarch, Queen Elizabeth II was celebrated in June in Canada as it was in the United Kingdom. But the next year it was moved to the Monday immediately preceding 25th May and Victoria Day was also moved from 24th May to that Monday. Victoria Day was so identified with the Monarchy, past and present, that the two celebrations were re-united. This was made permanent in 1957 by royal proclamation. And that is the situation today. The Official Birthday of Queen Elizabeth II and Victoria Day are two separate holidays but both are celebrated on the Monday that falls between 18th and 24th May inclusive.

A word should also be said about Empire Day. In some jurisdictions Empire Day was celebrated on 24th May, in England for example from 1904, and it is sometimes confused with Victoria Day. In Ontario Empire Day was the school day immediately prior to Victoria Day (i.e. 23rd May until 1953, unless that was a Saturday or a Sunday, in which case it would be the Friday before, and from 1953, always on the Friday before Victoria Day). Although it was an Empire and Commonwealth-wide celebratrion, it too was started in Canada – in Dundas, Ontario – by Clementina Trenholme Fessenden in 1898 (actually before Victoria Day was created from the Queen’s Birthday). In 1977 the date was changed to the second Monday in March and it was renamed Commonwealth Day (a name which it had been given in the United Kingdom in 1959). It was not made a public holiday however, remaining, as it began, as a school day for students to learn about the Commonwealth.

The second element in the success of Victoria Day is Canadian weather. In Britain spring comes in March, or even in February, as it does in much of Europe and the United States. In Canada spring doesn’t really come at all. We have what we call spring for a short period in April and May, but most of the world would say we go from winter to summer overnight (or over a few days) on some occasion within those two months. Either by coincidence or Divine intervention, reliably nice weather does not arrive in Canada until the Queen’s Birthday, giving real meaning to the term “Queen’s Weather”, even though it often rains on Victoria Day itself. As a result the Monarchy and summer weather became synonymous in Canada, and certain social customs developed around the day. One did not wear white before Victoria Day, gardens were not planted until then, cottage season did not begin until then. Since the short Canadian summer is so looked forward to by Canadians, the holiday gained added significance in their lives.

Finally, Victoria Day became a successful holiday because its focus is outward looking rather than inward looking for the celebrants. As important as Canada Day is, for example, it remains a holiday when government encourages us to tell ourselves how great we are. Deep down Canadians remain somewhat uncomfortable about that. It is like throwing a birthday party for yourself because you don’t think anyone else will. We are more comfortable when the United Nations says we are a good country than when we say it ourselves. Arguably the most successful Canada Day celebrations in Ottawa were those in 1959, 1967, 1990, 1992 and 2010 when the Queen was present or 2011 when the Duke of Cambridge attended. As our Sovereign and head of the national family, and our future Sovereign, the Queen and the Duke told Canadians that we, their people, were a good people they were proud of. That was natural and it felt good. On the Queen’s Birthday we are reciprocating by telling the Sovereign that she (or he, in the future) is a good monarch, whom we are proud of as the head of our national family.

In conclusion, the Queen’s Birthday and Victoria Day remain important joint holidays celebrated in Canada in the 21st Century because they were given life by the Canadian people. The celebrations are neither an imported tradition nor an artificial creation force-fed by government. Celebrating both a beloved monarch of our history and the reigning monarch of Canada ensures that the festivities are rooted in our history but will never be archaic or stale. Like the Monarchy itself, they are constantly being renewed in significance and style of celebration by the life and personality of the Sovereign of Canada to whom the tribute is given, and by the collective personality of the Canadian people by whom it is offered.

-----------------------

Queen Victoria, 1837-1901: Mother of Confederation

by Arthur Bousfield

Queen Victoria grew up knowing a lot about Canada. Her father, the Duke of Kent (Prince Edward, fourth son of King George III), had lived for nearly ten years in Quebec and the Maritimes in the last decade of the 18th Century and had travelled as far inland as Newark (Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ontario). As a young Princess, Victoria received the Bouchettes, the Quebec topographers, at Kensington Palace in 1832. The many well-known photographs of Victoria at the end of her life have stamped people’s minds with the image of her as an old lady, but it was as a charming young girl of 18 that she came to the Throne.

She inherited the Crown after a period of royal unpopularity, scandals and family discord. “I will be good”, she said at age 10, when she realised that she would likely become Queen; and she lived up to this resolve. A wave of enthusiasm greeted her accession and everyone was moved by the great presence and dignity shown by the short (barely five foot) blue-eyed, fair- haired monarch. Her accession coincided with the rebellions of 1837 in Upper and Lower Canada and her diaries reflect those unhappy events. For her coronation in 1838 an amnesty was granted to the Upper and Lower Canada rebels as part of the celebrations and the young Queen talked Lord Durham into accepting the post of Governor-in-Chief of Canada to study reforms for the provinces in the wake of the rebellion.

Just as her grandfather King George III will always be identified with the existence of Canadians as a separate people in North America, so Queen Victoria is forever linked with the birth of a unified Canadian state. Before Confederation came about the Queen made clear that she strongly favoured it. Her father after all had proposed a similar scheme as early as 1814. “I believe it will make [the provinces] great and prosperous”, she told Sir Charles Tupper, one of the principal fathers of Confederation.

It was on 1st July 1867 that Her Majesty proclaimed the Confederation of the first four provinces of Canada and at the same time summoned the first members of the Senate of the new Dominion. To underline the inseparable bond between Crown and Confederation, Sir John Alexander Macdonald, first Prime Minister of the new Canada, whom Queen Victoria received in audience on the eve of the great event, told her that the purpose of Confederation was “to declare in the most solemn and emphatic manner our resolve to be under the sovereignty of Your Majesty and your family forever”. Loyalty to the Crown was the keystone of Confederation, the only common bond that could overcome the strong sectional character and feelings of the provinces. Even the ship that carried the delegates from the Province of Canada to Prince Edward Island for the 1864 Charlottetown Conference that led to Confederation was named the Queen Victoria. Victoria has rightly been called the “Mother of Confederation”.

Queen Victoria twice chose Ottawa as the capital, first in 1857 for the Province of Canada and then again in 1867 for the Dominion of Canada. She named British Columbia in 1858 and the City of New Westminster in 1859, and chose the pitcher plant as the flower of Newfoundland in 1865. She also assigned the coats of arms of the provinces of Ontario, Quebec and New Brunswick in 1868. She gave the royal charters of the universities of Laval in1852 and of Trinity in 1851. In 1879 she contributed money for the preservation of the historic walls of Quebec City and paid for the erection of the city’s Kent Gate in memory of her father. After the great fire of 1890 at the University of Toronto, Victoria made a personal donation towards the restoration. Regina and Victoria were named in her honour, and the Province of Alberta after her fourth daughter Princess Louise Alberta. More counties, districts, villages, streets, parks and schools are named after her than after any other individual in Canada. The main roads of inumerable Canadian communities, as large as the City of Toronto or as small as the Village of Neustadt, Ontario, are named “Queen Street”. As part of the Canadian reaction to the Annexation Manifesto of 1849 (a drive by some Montreal business leaders for union with the United States), the Queen’s Birthday became a major national holiday and is still celebrated each year on the Monday preceding the 25th May. (Victoria Day, as it became in 1901 in memory of the Queen, is also the celebration of the reigning monarch’s official birthday.) Schoolchildren once invented the chant: “The twenty-fourth of May is the Queen’s birthday. If we don’t get a holiday, we’ll all run away”.

When invited by unanimous resolution of the Parliament of the Province of Canada (modern Ontario and Quebec) in 1858 to tour the province, Queen Victoria declined but sent her eldest son, the Prince of Wales (Edward VII), instead. It was not fear of the ocean voyage, unwillingness to endure the fatigue of such a long tour or lack of interest that made her refuse, but rather the reluctance she felt about leaving Britain in the hands of the politicians for several months. Though never personally present in Canada, Canada was never far from her mind or she from the minds of Canadians. When the last spike was driven into the Canadian Pacific Railway joining Canada from the Atlantic to the Pacific and the first train arrived in Vancouver from Montreal in 1886, the news was immediately telegraphed to Queen Victoria as “Canada linked!”

At various times the Queen sent four of her sons and one daughter to Canada. Queen Victoria was the patron of Canadian artists such as Madam Albani, Lucius O’Brien, Frederic Bell-Smith and Homer Watson. She honoured many Canadian statesmen and was involved with a host of other Canadian public figures. At her Diamond Jubilee in 1897 Canada’s gift to her was the establishment of the famous “Victorian Order of Nurses”, which has helped millions of Canadians through illness, convalescence or disability. In 1896 she established the Royal Victorian Order, an order of chivalry for personal service to the monarch to which Canadians continue to be appointed to this day.

Queen Victoria’s sixty-three year reign (second only to King Louis XIV of our monarchs) coincided with the zenith of the second British Empire. Her assumption of the title “Empress of India” in 1877 symbolised this fact. Development of Dominion status by Canada in 1867 provided a model for the peaceful transition of empires into independent states, that was adopted thoughout the world in the following century. When the Queen’s Golden Jubilee was celebrated in London in 1887, twenty years after Confederation, the Premiers of the ten self-governing overseas provinces in addition to Canada (the first of them) gathered there to hold what was, in effect, the first Commonwealth Conference.

Victoria was a liberal monarch in the very best sense of the word. She urged her government to be merciful to her Indian subjects following the Mutiny in 1858, as she had for the Canadian rebels in 1837. On another occasion she deplored “the violent abuse of the Catholic religion” that was then taking place in public. And when it came to the question of race, Victoria was truly colour blind. A black from Nova Scotia was the second Canadian to receive the Victoria Cross (the highest decoration for bravery under fire) only two years after the Queen established it in 1856. American slaves hoping to escape to freedom in Canada by the underground railway made up a song called Away to Canada with the verse: “I heard old Queen Victoria say if we would all forsake / Our native land of slavery and come across the lake, / That she was standing on the shore with arms extended wide / To give us all a peaceful home beyond the rolling tide”. When the Queen received Kahkehwahquonaby, the Ontario Mississauga Chief, at WindsorCastle in 1838 she allowed him to wear native dress instead of the usual court dress customary for such occasions. Towards the end of her reign she refused to part with an unpopular Indian servant because she felt people were prejudiced against him simply because of his colour.

In 1840 Queen Victoria married her first cousin, Prince Albert of Saxe-Cobourg-Gotha. It was a love match and the couple had nine children. Victoria’s handsome German Prince was a man of considerable talent, a political philosopher who had an earned PhD, a musician and composer, an excellent administrator and an indefatigable worker. Prince Albert originated the highly successful Great Exhibition of 1851 that led to the erection of Crystal Palaces in many major Canadian cities. Even more important for Canada’s destiny, he helped avert a war with the United States in 1861. Prince Albert, Saskatchewan (represented in the Canadian Parliament for many years by the Prime Minister and great royalist John Diefenbaker) is named for him. The Prince became the Queen’s Private Secretary and was so efficient and influential that from 1840 to 1861 there was almost a joint monarchy.

During Victoria’s reign the modern practice of constitutional monarchy took shape and the Queen learned from her husband that to continue to exert royal influence she had to work hard and regularly. When the Prince Consort (as Queen Victoria created Albert) died in 1861, Victoria was heart broken and, in her grief, wore black clothes for the rest of her life and withdrew into seclusion, an action that made the Monarchy temporarily unpopular in the United Kingdom, though not in Canada. Gradually the Queen reappeared in public and one of her last public acts before her death in 1901 was to review Canadian troops returning from the South African War via London.

Once coming upon a courtier misbehaving in the Palace, Queen Victoria said: “We are not amused!” and passed on. This remark has led to her being labelled as humourless. Nothing could be further from the truth. She possessed a charming smile, laughed heartily, loved fun and had a great sense of humour. She had a passion for opera and the theatre and a real gift for drawing and painting. Mendelssohn said that she had the finest amateur singing voice he had ever heard. She spoke French, German and Italian as fluently as she did English and was the author of two books. Victoria’s prestige was so great internationally that the century in which she lived is known as the “Victorian Age”, even in republics like the United States.

John Diefenbaker described the day of her death in his memoirs: “When Queen Victoria died, Father regarded it as one of the most calamitous events of all time. Would the world ever be the same? I can see him now. When he came home to tell us the news, he broke down and cried.”

---------------

Victoria Day- CANADA

Victoria Day is a statutory

holiday remembered informally as "the twenty-fourth of May,” or “May

Two-Four.” Originally a celebration of Queen Victoria's birthday, the holiday

now marks Queen Elizabeth II's birthday as well. Victoria Day was established

as a holiday in the Province of Canada in 1845 and as a national holiday in

1901. It is observed on the first Monday before 25 May.

Victoria Day is a statutory

holiday in every province and territory except Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador and Prince Edward Island. The holiday was officially

renamed Journée nationale des Patriotes (National Patriotes Day) in Québec in 2002.

The Monarch’s

Birthday in Canada

While the king or queen’s birthday has been celebrated in

Canada for centuries, before Queen Victoria ascended to the throne in 1837, it was

more of a military occasion than a civilian holiday. In 18th-century British North America, the monarch’s birthday was

the day on which local militias engaged in compulsory annual training. The

able-bodied men of each community would march with their weapons in the town

square then toast the King at local taverns and alehouses. When members of the royal family visited, they would attend these reviews and

celebrations. During the 1790s, Queen Victoria’s father, Prince Edward, the

Duke of Kent, resided in British North America, attending military reviews each

spring.

Origins of Victoria

Day

In 1841, the parliaments of Upper and Lower Canada were replaced by a single

legislative assembly for the Province of Canada. The new assembly sought

opportunities to create common ground between English and French Canadians that

would transcend religious and cultural differences. A public holiday honouring

the young Queen Victoria’s birthday, 24 May, was an idea that

appealed to both English and French Canadians. At the time, loyalty to the Crown was a key cultural trait that distinguished

Canadians from Americans and the monarch (the king or queen) was considered a

guarantor of minority rights in the united province. In 1845, the legislative

assembly of the Province of Canada declared the Queen’s birthday an official

public holiday, transforming the monarch’s birthday from an exclusively

military occasion to a civilian holiday.

Celebrations

The new public holiday was

comparatively quiet during the 1840s, but the celebrations grew over the course

of the 19th century — Canadians, it seemed, embraced an occasion that combined

the prevailing loyalty to the Crown with the transition to warmer weather. On

Queen Victoria’s 35th birthday in 1854, 5,000 people

gathered outside Government House in Toronto to give cheers to the Queen. The effusive

Toronto celebrations set the tone for the rest of Canada. By the time of Confederation in 1867, communities in Québec and Ontario held all-day Victoria Day celebrations

that included parades, picnics, athletic competitions, military reviews and

fireworks displays. The official festivities spread across Canada as new

provinces joined Confederation. Victoria Day was not always part of a long

weekend, as the holiday took place on the day of the Queen’s birth, 24 May,

regardless of the day of the week.

The Sinking of the

Victoria on the Thames

In 1881, on Queen Victoria’s 62nd birthday, the festivities in London, Ontario, ended in tragedy. The riverboat Victoria

carrying hundreds of people back to downtown London from celebrations at

Springbank Park capsized, drowning at least 182 of its passengers. The

steamboat wasdesigned for a maximum capacity of 400, but wascarrying 650

people. When passengers sighted a rowing club race near Cove Bridge, they

gathered on the right side of the ship to watch. The weight capsized the ship

and collapsed the top deck. The passengers who died, mostly women and children,

drowned less than 10 m from the shore. The sinking is one of the worst marine disasters in Canadian history.

Victoria Day after

Victoria

When Queen Victoria died in 1901, and was succeeded by her

son, Edward VII, Victoria Day remained a public holiday on 24 May. While other

parts of the English-speaking world celebrated 24 May as Empire Day, Canada honoured Queen Victoria as a

“Mother of Confederation” who encouraged Canadian unity and self-government and

selected Ottawa as “the Westminster of the wilderness.”

From the death of King Edward VII in 1910 until the second year of Queen

Elizabeth II’s reign (1953), the monarch’s birthday was separate from Victoria

Day, which honoured Queen Victoria’s unique contribution to Confederation.

The Modern Holiday

In 1939, Victoria Day was treated

as King George VI’s official birthday in Canada because the holiday took place

when he and Queen Elizabeth were touring Canada — George VI’s

actual birthday was 14 December (see 1939 Royal Tour). With the ascension of Queen Elizabeth II in 1952, Victoria Day became the

Queen’s official birthday in Canada (actual date of birth 21 April 1926) and

was fixed on the Monday before 25 May of each year, creating the modern long

weekend. As in the 19th century, Victoria Day marked a transition to warmer

weather. The modern holiday has become associated with the opening of seasonal

getaways (cottages, cabins, chalets), barbecues and outdoor festivals. It is

referred to, informally, in this context as “May long weekend” and the

“Victoria Day long weekend,” but also “May Two-Four” in some parts of Canada.

While Québec officially celebrated the holiday as

Victoria Day, the celebration also became unofficially known as the fête de

Dollard (after Adam Dollard des Ormeaux, a colonist and soldier

of New France) during the 1920s. The Québec holiday

was officially renamed Journée nationale des patriotes (National

Patriotes Day) by the provincial government in 2002. This holiday highlights

the Patriotes’ struggle for political freedom and for

the development of a democratic system of government during the Rebellions of 1837–38.

In

2013, an online petition circulated to rename the holiday Victoria and First

Peoples Day. While the initiative attracted the support of certain well-known

Canadians such as Margaret Atwood, the petition only attracted

1,500 signatures and the holiday remained unchanged. Canada’s Victoria Day has

few parallels around the world. In parts of Scotland, schools close on the

Monday before 25 May to honour Queen Victoria’s contributions to Scottish society, but

Victoria Day is not a national bank holiday. Belize celebrates Commonwealth

Day, the successor of Empire Day, on 24 May. Only in Canada, however,

does Queen Victoria’s birthday remain a national holiday.

-----------------

May 5, 2015

CANADA MILITARY NEWS:

May5/15 O CANADA -TODAY IN HISTORY:

May 5- In 1900 , Pte. Richard R.Thompson of Ottawa was awarded the Queen’s scarf for gallantry during the Boer War. Knitted by Queen Victoria, the scarf was awarded only seven times.

Queen Victoria crocheted five Scarves of Honour during the war in South Africa for presentation to “soldiers in Forces of her Overseas Dominions." Thompson, who died in 1908, served with the 2nd Special Service Battalion. His scarf is on permanent loan to the National War Museum.

May 5- In 1900 , Pte. Richard R.Thompson of Ottawa was awarded the Queen’s scarf for gallantry during the Boer War. Knitted by Queen Victoria, the scarf was awarded only seven times.

Queen Victoria crocheted five Scarves of Honour during the war in South Africa for presentation to “soldiers in Forces of her Overseas Dominions." Thompson, who died in 1908, served with the 2nd Special Service Battalion. His scarf is on permanent loan to the National War Museum.

Canada Boer War

-----------------------

QUEEN VICTORIA’S SCARVES

In

a simpler time, when soldiers wore scratchy-wool battledress, a

number of uniquely military legends circulated freely through the

ranks. Like urban legends of giant alligators lurking in sewers and

hook-handed psychopaths haunting lovers’ lanes, the origins of

these legends were lost in time. Again like the urban legends, most of

these legends, such as that of Queen’s Corporals who could not be

rebuked by anyone short of Her Majesty, were little but sheer

fantasy.1.

Unfortunately, the story of Queen Victoria’s scarves has become a

Canadian military legend in its own right. As the story goes,

Private Richard Rowland Thompson of the 2nd

Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, was recommended for the

Victoria Cross once or, by some accounts, twice, but received one of

the khaki-wool scarves crafted by Queen Victoria instead.

Furthermore, some authoritative sources have suggested this award

may even rank above the VC.2.

Even such highly respected Canadian historians as Jack

Granatstein, David Bercuson and Carmen Miller have perpetuated the

myth in recently-published works.3.

A sub-set to the legend has that Thompson was a medical assistant

or perhaps a stretcher bearer; as a consequence the Canadian Forces

Medical Service laid claim to his legacy and named a building after

him. While researching my book on the Canadians in the South African

War4.,

I realized that much of what I had accepted as gospel about the

scarves was suspect. With the manuscript safely in the hands of my

publisher and fuelled with the righteous zeal of the newly-converted,

I decided to do some digging to separate facts from fiction. My aim

is to share the information I gathered over some four years from

sources in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the United

Kingdom, and the United States.

In

a simpler time, when soldiers wore scratchy-wool battledress, a

number of uniquely military legends circulated freely through the

ranks. Like urban legends of giant alligators lurking in sewers and

hook-handed psychopaths haunting lovers’ lanes, the origins of

these legends were lost in time. Again like the urban legends, most of

these legends, such as that of Queen’s Corporals who could not be

rebuked by anyone short of Her Majesty, were little but sheer

fantasy.1.

Unfortunately, the story of Queen Victoria’s scarves has become a

Canadian military legend in its own right. As the story goes,

Private Richard Rowland Thompson of the 2nd

Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment, was recommended for the

Victoria Cross once or, by some accounts, twice, but received one of

the khaki-wool scarves crafted by Queen Victoria instead.

Furthermore, some authoritative sources have suggested this award

may even rank above the VC.2.

Even such highly respected Canadian historians as Jack

Granatstein, David Bercuson and Carmen Miller have perpetuated the

myth in recently-published works.3.

A sub-set to the legend has that Thompson was a medical assistant

or perhaps a stretcher bearer; as a consequence the Canadian Forces

Medical Service laid claim to his legacy and named a building after

him. While researching my book on the Canadians in the South African

War4.,

I realized that much of what I had accepted as gospel about the

scarves was suspect. With the manuscript safely in the hands of my

publisher and fuelled with the righteous zeal of the newly-converted,

I decided to do some digging to separate facts from fiction. My aim

is to share the information I gathered over some four years from

sources in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, the United

Kingdom, and the United States.Queen Victoria’s concern for her army was exemplified by her gift of a box of chocolate to every soldier serving in South Africa at the end of 1899. The boxes, which measure approximately 7″ by 3″ by 1″, featured an embossed portrait of the Queen, flanked by the royal cypher VRI surmounted by a crown and “South Africa 1900,” above, in her hand, the signed message “I wish you a happy New Year.“5. For Her Majesty to further express her feelings by presenting scarves crocheted by her own hand to her army was very much in character. It was clearly impossible for the elderly monarch to crochet a scarf for everyone, so she may have decided to symbolically recognize the contribution of all by rewarding a select few.

It would be most unfortunate if her visit to Netley hospital a few days after the battle of Paardeberg influenced her decision. During the visit the only wounded Canadian patient, Private A.E. Cole of B Company, 2 RCR, was presented to her. In response to her inquiry, he replied that he had been wounded during the action at Sunnyside on 1 January 1900. The Queen then “expressed sympathy with Cole’s suffering and showed a kind appreciation of the loyalty displayed by his comrades and himself in volunteering for active service.” The encounter received extensive press coverage in both the United Kingdom and Canada. In fact, Cole had shot himself in the foot while loading his rifle in camp on 16 January 1900, and had lied to avoid embarrassing himself, his regiment and his country. Whether the encounter with Cole resulted in her decision to craft the scarves is doubtful. As the first four scarves were shipped to South Africa in April 1900, she may have been already crocheting the scarves at the time of her visit to the hospital. The meeting with Cole may have done nothing more than increase her resolve.6.

Most likely, we will never know, but I lean towards the theory that the Queen was already working on the scarves before her visit to Netley Hospital.7.

How

many scarves did the Queen crochet? The number of scarves has been

authoritatively (and wrongly) stated as four, five, six, and seven.

As we shall see, the actual number produced probably was the result

of an appreciation for the sensibilities and feelings of her

subjects around the world. At the time the contribution of the

self-governing “colonies” was very much in the public eye. Therefore,

a scarf should go to each of the Canadian, Australian, New Zealand,

and South African contingents. However, the presentation of

scarves to the colonial contingents could be seen as a slight to the

regular army, which was bearing the brunt of the fighting. This

would seem to lead to the conclusion that a minimum of four scarves

was required for the regulars. In fact, this is what the Queen decided

upon. In the last year of her long life, Queen Victoria crocheted

eight khaki Berlin wool scarves8.,

each approximately five feet long by eight inches wide. Her Majesty

had sent four to Field Marshal Roberts, the Commander-in-Chief of the

South African Field Force, for “distribution to the four most

distinguished private soldiers” in the Canadian, Australian, New

Zealand and South African forces9.

and, somewhat later, four more scarves to her grandson, Major Prince

Christian Victor, for presentation to members of the British

regular army.10.

How

many scarves did the Queen crochet? The number of scarves has been

authoritatively (and wrongly) stated as four, five, six, and seven.

As we shall see, the actual number produced probably was the result

of an appreciation for the sensibilities and feelings of her

subjects around the world. At the time the contribution of the

self-governing “colonies” was very much in the public eye. Therefore,

a scarf should go to each of the Canadian, Australian, New Zealand,

and South African contingents. However, the presentation of

scarves to the colonial contingents could be seen as a slight to the

regular army, which was bearing the brunt of the fighting. This

would seem to lead to the conclusion that a minimum of four scarves

was required for the regulars. In fact, this is what the Queen decided

upon. In the last year of her long life, Queen Victoria crocheted

eight khaki Berlin wool scarves8.,

each approximately five feet long by eight inches wide. Her Majesty

had sent four to Field Marshal Roberts, the Commander-in-Chief of the

South African Field Force, for “distribution to the four most

distinguished private soldiers” in the Canadian, Australian, New

Zealand and South African forces9.

and, somewhat later, four more scarves to her grandson, Major Prince

Christian Victor, for presentation to members of the British

regular army.10.Rather than attempt to select the four most deserving regular soldiers from the ranks of the army — a task that was fraught with pitfalls — the Prince, who was then serving in the headquarters of the 5th Division in Natal, forwarded a scarf to each of the four battalions of the 2nd Brigade, the formation he had served with prior to his posting to the 5th Division’s headquarters.

The 2nd, or English, Brigade was made up of four home-based battalions and had been ordered to South Africa as part of the army corps mobilized on 7 October 1900. By the time the brigade arrived at Cape Town in November, the situation in Natal had deteriorated badly. As a result General Sir Redvers Buller, the Corps Commander, decided to break-up the corps and diverted the 2nd Brigade to Durban. In effect, this led to two separate armies. Field Marshal Roberts, who had been ordered to South Africa to take command of the forces in South Africa in December 1899 after the shock of “Black Week,” also led the South African Field Force facing the Boers astride the western and central railway lines. Buller commanded the Natal Field Force attempting to relieve the siege of Ladysmith and drive the Boers from Natal. The 2nd Brigade, led until April by Major-General H.J.T. Hildyard, had fought at Willow Grange, Colenso, Spion Kop, and the relief of Ladysmith.11. By mid-1900 the brigade had entered the southern Transvaal and taken up positions guarding the railway in the Standerton area.12 Based on the Natal Field Force’s status as a quasi-independent command, it is possible that Roberts was not aware of the existence of these scarves at the time or after the event.

Each of the battalions presented its scarf to a colour sergeant, the senior non-commissioned officer in a rifle company, although this may have been more by coincidence than design. The four recipients were Colour Sergeants Frank Kingsley, 2nd Battalion the West Yorkshire Regiment; Thomas William Colclough, 2nd Battalion the Devonshire Regiment; Henry Clay, 2nd Battalion the East Surrey Regiment; and F.F. Ferret, 2nd Battalion the Royal West Surrey Regiment. The commanding officer of the West Yorks wrote that Kingsley “has been in every engagement with the Regiment and at Spion Kop he distinguished himself by the way he commanded his company when his Captain was killed and the other officer of his company wounded. He is a most deserving man in every way and a brave soldier.” One can safely assume that the other three NCOs were equally deserving.13

While the four colour sergeants were good soldiers and brave men, the Prince’s actions were arbitrary and perhaps did not do justice to Her Majesty’s intentions. However, the Queen apparently had left the details of the distribution to him and one can only hope, perhaps futilely, that he was not engaging in a bit of military nepotism or taking the path of least resistance. Whatever his reasons, the Prince’s actions served to lessen the status of the scarves as a recognition of gallantry in action.

The four “colonial” scarves were distributed in a more formal and systematic manner. In his despatch of 1 March 1902 Lord Roberts wrote that In April 1900, her late Majesty Queen Victoria was graciously pleased to send him four woollen scarves worked by herself, for distribution to the four most distinguished private soldiers in the Colonial Forces of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, then serving under his command. The selection for these gifts of honour was made by the officers commanding the contingents concerned, it being understood that gallant conduct in the field was to be considered the primary qualification.14

The Canadian recipient was, of course, Private Richard Rowland Thompson, of D Company, 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry. He was selected in early July 1900 “after considerable discussion” by a committee made up of his battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel William Dillon Otter, the battalion staff, and the company commanders. At the time the battalion was based at Springs on a railway branch line south-east of Johannesburg after having marched and fought its way from Paardeberg to Pretoria. The actual instruction to nominate a soldier had been sent to Otter on 21 April 1900 by Colonel Neville Chamberlain, the private secretary to Lord Roberts, shortly before Otter was wounded at Israel’s Poort on 25 April., which probably accounted for the delay in completing the selection. In the instruction Colonel Chamberlain wrote:

Her Majesty the Queen has forwarded four woollen scarves, worked by herself, to be distributed to the most distinguished soldier of the Australian, New Zealand, Canadian and Cape Colony Forces under Lord Roberts’s Command.

His Lordship desires me to ask you to nominate the

private soldier whom you consider has performed the most

distinguished service in the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry.15

|

In 1908, following Thompson’s premature death, the Canadian Department of Militia and Defence presented his family with a scroll that included the following citation:

The particular acts upon which Private Thompson was selected were as under:

| First, Having on the night of the Eighteenth-Nineteenth February 1900,

kept Private Bradshaw, who was left dangerously wounded at

Paardeberg, alive by the care and attention bestowed upon him, until

he could be properly attended to. Second, Having twice left the trenches on the morning of the capture of the Boer Laager at Paardeberg, the Twenty-Seventh February, 1900, at the imminent risk of his own life, for the purpose of assisting wounded comrades, lying some distance in front of the trenches. |

| Dear Dicky – I am just off to Wynberg and England. I’ve had a devil of a time and my recovery has been a complete surprise to everyone here, myself included. An operation, which would have taken place had I been fit, will have to be performed in the future. My heart’s gone all wrong and also my eyesight. Had it not been for you and Bull,ii I would have been a beautiful corpse long ere this. I really don’t know how to thank you sufficiently. words seem so cold and barren, and I hope when you visit Canada, you will give me a chance of proving my gratitude. You can always hear of me by writing the Standard Bank of Canada, Picton, Ontario. I hope you will never be placed in the same position as I am at present, and with best wishes for your safe conduct through what I am afraid is going to be a long, long war. Believe me,

Yours very sincerely,

James L.H. Bradshaw16 |

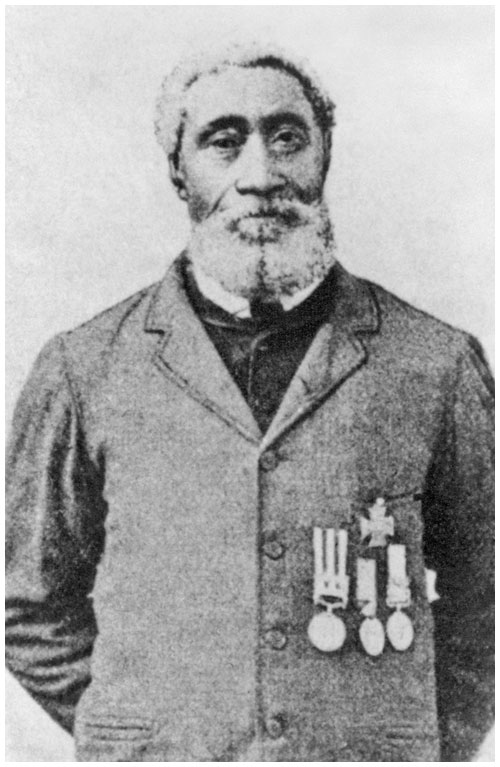

The only known picture of Private Richard Rowland Thompson |

Pte. R.R. Thompson is well known to many Ottawans as he spent the greater part of last summer in this city visiting friends. He was an Irish medical student from Dublin university, whether he had gone from Cork, his home. At the time that the first Canadian contingent was organized he was in Buffalo with a brother, but took the first train to Toronto, where he enlisted under Col. Otter. Subsequently he asked to be transferred to the Ottawa company, as he knew many of the boys belonging to it and this was done. Pte. Thompson has seen considerable of the world and had been connected with Dr. Jameson in his famous raid. He was well acquainted with that part of Africa in which the Canadians were engaged. When attending university he had been invited by an officer of the Rhodesian Horse to visit Rhodesia and he spent six or eight months in that country.“20

Another newspaper report, written at the time of his enlistment in October 1899, stated… The recruit Thompson is a medical student from Buffalo. He came recently from England and has spent several years in Natal, being acquainted with the country.

Yet another article on the same page detailed the results of an interview with Thompson, where he predicted the war would last about four months. The paper provided the following sketch, Mr R.R. Thompson, one of the members of the Ottawa detachment, came from Buffalo to enlist at Toronto, from which city he was sent by Lt.-Col. Otter. Thompson, who is a native of Cork, Ireland, is 22 years of age. He was engaged in business in Natal for the greater part of 1898.21

Thompson was not serving with the battalion at the time of his selection. At sometime between Paardeberg and the fall of Pretoria, one source says at Bloemfontein, he had fallen victim to sunstroke and was evacuated. Like Bradshaw, he was invalided to the United Kingdom22 and then returned to Canada. Dick Thompson was discharged at Quebec on 15 October 1900.

From the sketchy evidence it seems that Thompson then made his way to Buffalo, with a stop in Ottawa that was reported in that city’s press at the time. By this time, he knew that he had been selected to receive a Queen’s Scarf, as it had been reported in Canadian newspapers in August 1900.23 In early 1901 he was commissioned a lieutenant in the South African Constabulary and sailed to South Africa in April. Thompson served at Bloemfontein until he resigned his commission to take up employment with the DeBeers Corporation. In April 1904 he married Miss Bertha Alexander of Gatineau, Quebec (a small town a few miles north of Ottawa) in Bloemfontein. They returned to Buffalo shortly after, where he died of appendicitis on 6 April 1908. His widow accompanied his corpse to Ottawa and Thompson was interred in a small private cemetery near Chelsea, Quebec. Mrs Thompson eventually remarried but chose to be buried beside her first husband.

Capt Cybulski lays a wreath for 1 RCR at Grave of Pte RR Thompson, 11 Nov 2013, Chelsea Que

The other colonial recipients of scarves were Private Alfred Henry Dufrayer of C Squadron, the New South Wales Mounted Rifles, Private Henry David Coutts of the New Zealand Mounted Rifles, and Trooper Leonard Chadwick of Roberts’ Horse, a South African irregular mounted unit.25 After an Australian patrol was lured into an ambush near Karree Siding on 11 April 1900, Dufrayer had ridden back and rescued an unhorsed comrade who lay dazed and helpless within point-blank range of a party of Boers in a farmhouse.26 Both Coutts and Chadwick apparently won their scarves during the debacle at Sannah’s Post on 31 March 1900. Preoccupied by Boers actively pressing the rear guard, and moving on a “safe” route, the commander of a British column failed to deploy an advanced guard. As a result, the column’s transport and artillery blundered into an ambush set by the brilliant Boer leader, Christian De Wet, at a ford over Koornspruit. Roberts’ Horse, which was escorting the guns, lost at least a quarter of its strength in a matter of minutes. While Chadwick was not mentioned in the original despatch on Sannah’s Post, Roberts wrote that Chadwick had been selected by a unanimous vote of his comrades.27 The New Zealanders also saw a great deal of hard fighting as the disorganized column had to change its axis of withdrawal ninety degrees and retire along the river bank until it could reach another crossing place, all the time under heavy fire from two sides. During the withdrawal Coutts rode back under heavy fire to rescue a badly-wounded British mounted infantryman.28

It is significant that all four scarves were awarded for acts in February, March or April, although the army saw a great deal of fighting after that date, and that all went to members of the South African Field Force. This was in accordance with Roberts’s despatch cited above that, “in April 1900, her late Majesty Queen Victoria was graciously pleased to send him four woollen scarves worked by herself, for distribution to the four most distinguished private soldiers in the Colonial Forces of Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa, then serving under his command.”

Why did Thompson or any of the others not receive the VC? There is a simple answer — they were not recommended for the award. In later life Colclough claimed that the scarf could only be awarded to men who had been recommended for the Victoria Cross, while Dufrayer stated that he had won the VC, but was given the choice of accepting an immediate award of the Scarf instead. However, there is no record that any of the scarf recipients was ever recommended for the Victoria Cross — other than a unsuccessful recommendation for Thompson submitted by Otter after he had already received his scarf. As for Dufrayer’s claim, there is no such thing as a guaranteed award of the Victoria Cross. Either he was misled or he resorted to selective recollection in his life-long quest to gain VC status, and the accompanying pension, for his scarf. Three of the four colour sergeants, Colclough being the exception, were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. There are no indications that the medals awarded to the British colour sergeants were directly related to the scarves, and in fact, Clay won his medal while serving as the Regimental Sergeant Major of his battalion. Colour Sergeants Clay, Ferret, and Kingsley, Trooper Chadwickiii, a 21-year old American who had won the Medal of Honor at Cienfuegos, Cuba on 11 May 1898 during the Spanish-American War and Private Thompson were Mentioned in Despatches. Colclough, Coutts, and Dufrayer received no formal recognition. Considering that the majority of VCs awarded during the first year of the war were for rescuing comrades under fire, if a recommendation for a VC for Thompson, Dufrayer or Coutts had been submitted, it may well have been successful.29

The press had, and continues to have, a field day with the scarves. For example, at the time of the formal presentation of the scarf to Dufrayer by the Duke of York in Australia in 1901, wildly fanciful, and completely false, claims were made by the Australian press. Sixty years later, Canadian public affairs staff attempted to reconstruct the story of Thompson and his scarf. Unfortunately, some errors were made at the time because of a combination of enthusiasm and inadequate research. The passage of time has elevated these errors to the status of dogma. To quote an example, a Department of National Defence press release of 9 September 1964 claimed that: Conditions for the award were of the highest order. Soldiers nominated for the award must have entered the war or Army as “rankers,” and they had to be first recommended for the Victoria Cross, with subsequent recommendations for bravery in the field. The award was to run equally with the Victoria Cross, and was to be awarded by a vote of comrades in the field. Individuals winning the award who were later commissioned were to carry their rank for life.

According to Australian Army orders, the Queen’s Scarf of Honour ranked equally with the Victoria Cross, but other authorities regarded it as of even higher honour and value. This was due to the fact that Trooper A.H. Dufrayer, New South Wales Mounted Infantry, was recommended for the Victoria Cross and Bar, but was awarded the “Queen’s Scarf of Honour” instead.30

The public affairs staff failed to explain the relevance of an Australian Army order to the Canadian Army, or how someone could be recommended for the Victoria Cross and Bar. I have been unable to locate a copy of the order, which is a mystery to the Australians as well. The reference to a Victoria Cross and Bar has led to the totally unsubstantiated claim that Thompson was recommended for the VC twice. It is interesting to contrast the breathless and rather unprofessional tone of the Canadian press release with a New Zealand Army letter of 21 July 1964 that answered a media query with: Contemporary papers described the Queen’s Scarf as a gallantry award ranking next to the Victoria Cross but it was never officially recognized as a decoration in the Army list. There is nothing to indicate that Trooper [sic] Coutts was ever recommended for the VC or other gallantry award.31

This leads to the question of the status of the scarves. We have already seen the New Zealand position above. Thompson’s name did not appear in the list of Canadians decorated in the war published in the 1903 edition of the Canadian Almanac and Miscellaneous Directory, although the name of Squadron Sergeant Major G.F. Routh of Strathcona’s Horse, whose medal appeared in the London Gazette after Roberts’s despatch announcing the distribution of the scarves, was included. Both Dufrayer and, following his death, his son pressed the British authorities for three decades to recognize the award of the scarf as the equivalent of the Victoria Cross. The British have consistently maintained that the scarves, while a unique honour in their own right, do not rank with the Victoria Cross and have no official standing as gallantry awards. There is ample justification to support this position. While space does not permit a detailed explanation, note that Field Marshal Roberts referred to the scarves as gifts to be distributed and that gallant conduct was to be the primary, not the only, qualification. It is also significant that selection of the recipients was delegated to the contingent commanders. The award of the Victoria Cross (and the Distinguished Conduct Medal) required the approval of the sovereign. If the scarves ranked with the VC, selection surely would not have been delegated. Last, a note in the Royal Archives in Windsor Castle prepared at the time of the centenary of the Victoria Cross, recognized that “in a certain sense the Scarves may be regarded as a greater honour, stitched as they were by the hands of the Queen herself, and strictly limited in number. But whatever their relative status, they can hardly be treated as the precise equivalent of the VC.” The note also observed that the scarves were awarded on a different basis from the VC, and correctly, if somewhat haughtily, added that just because someone is the bravest private soldier in a particular contingent that is not, of itself, sufficient qualification for the award of a VC.32

In an era where movies such as Saving Private Ryan and U-571 have led to resentment by British and Canadian veterans and others over American “horn blowing” over their role in single handedly defeating the Nazis in World War Two, it is perhaps fortunate that the Americans have not noticed that Chadwick was an American citizen and Thompson was residing in the great republic on the outbreak of the war. (It seems that Thompson spent only a few months of his life in Canada — remember Bradshaw’s plea, “I hope when you visit Canada, you will give me a chance of proving my gratitude.”) The thought of Tom Hanks saving Private Bradshaw boggles the mind.

Finally, a few words about the current state of the scarves. The scarves awarded to Colour Sergeants Ferret and Clay are in museums in Guildford and Dover, respectively, in the United Kingdom. Dick Thompson’s scarf is in the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, while Dufrayer’s scarf is displayed in the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. In 1913, following the deaths of his wife and only child, Coutts presented his scarf to his country. While this scarf was originally displayed in the Parliament building in Wellington, it is now in the Queen Elizabeth II Army Memorial Museum at Waiouru. The fate of the other three scarves is unknown. Colour Sergeant Colclough emigrated to Canada after he left the British army, earned a commission in the 106th Winnipeg Light Infantry in early 1914, and served overseas as a major during the First World War. After the war he resumed his militia service, rising to command the Winnipeg Light Infantry. Colclough died in 1955. A picture of Colclough’s son holding the scarf appeared in the Toronto Globe and Mail in April 1965. The son, who was living in Banff at the time, had also contacted the Canadian office of Time magazine. His scarf is believed to be in the possession of his family in western Canada. Kingsley died in the Royal Hospital, Chelsea in 1952 while Chadwick passed away in Boston, Massachusetts in 1940. The trail of their scarves is very cold, and it is possible that they have not survived.33

While the story of the Queen’s Scarves is not exactly what we have been led to believe, one thing remains as true today as it was nearly a century ago — Thompson and his comrades rank among the very bravest in an army of very brave men.

NOTES

ii. This probably is a reference to Private E.W. Bull of Cobourg, Ontario, a fellow member of D Company and the only member of the battalion with that surname. His role in the affair is unknown, but it was noteworthy enough to earn a mention by Bradshaw.

iii. Leonard Chadwick should not be confused with Trooper J. Mckinty Chadwick, also of Roberts’ Horse, who received the DCM based on a recommendation dated 3 August 1901, nearly six months after Leonard Chadwick had left South Africa.

1. A British publication, Soldier magazine, recently reviewed the issue of King’s Corporals. There is some archival evidence to support the existence of the rank, such as the 1885 report that Lord Wolseley had promoted Lance Corporal A.A. Edwards to the rank of Queen’s Corporal for gallantry weathering a storm in the garrison boat at Harwich. However, in a Parliamentary answer in October 1944 the War Minister, Sir John Grigg, said there was no factual basis for any such rank. It appears that King’s, or Queen’s, Corporals may have been an appointment, rather than a rank, and therefore local or transitory. It would have been a very brave, or foolish, soldier who attempted to invoke special privilege as a defence. “New slant on ‘myth’ of King’s Corporal” in undated extract from Soldier provided by Les Peart of Ottawa.

2. See the stories in the OttawaCitizen of 24 Apr 95 and the Globe and Mail of 25 Apr 95. On 5 May 97 the Globe and Mail stated that Thompson had been recommended for a VC, but received a scarf instead.

3. Granatstein, J.L. and D.J. Bercuson. War and Peacekeeping: From South Africa to the Gulf — Canada’s Limited Wars, Toronto: Key Porter Books, 1991 p 58; Miller, Carmen. Painting the Map Red: Canada and the South African War, 1899 – 1902. Montreal: Canadian War Museum and McGill-Queen’s, 1993, p 108

4. Our Little Army in the Field, The Canadians in South Africa 1899 – 1902. St. Catherine’s: Vanwell Publishing Limited, 1996

5. The description is taken from a box in my possession. The boxes were discussed in Soldiers of the Queen, Issue 75, Dec 93

6. Cole’s file in the National Archives, and the diary of Private Floyd, another member of B Company, confirm that Cole was accidently wounded on 16 Jan 1900. Birch, James H., Jr. and Henry David Northrop. History of the War in South Africa. London, Ont.: McDermid & Logan, 1900 p 529

7. The Duchess of York, the future Queen Mary, remarked during a tour of Australia that she had helped the aged monarch “when she had dropped stitches whilst working the scarves.” One may question how much time Queen Victoria could have devoted to the scarves each day, given the state of her health and the demands of official and family obligations on the octogenarian monarch. Alan Hardfield, “Queen Victoria’s Scarves,” The Journal of the Orders and Medals Research Society, November 16, 1998 Vol. 32, No. 2, 1993, p 157

8. Berlin wool was the term used for crochet wool.

9. Roberts, Frederick Sleigh. ‘Final Despatch’ South African War Honours and Awards 1899 – 1902 London: Army and Navy Gazette, 1902, republished by Arms and Armour Press 1971, p 106

10. Creswicke, Louis. South Africa and the Transvaal War Vol 6 Toronto: The Publishers’ Syndicate, 1901 pp 123 – 4; Riall, Nicholas. ‘Queen Victoria’s Scarves’ in Soldiers of the Queen, The Journal of the Victorian Military Society Issue 80, March 1995 p 10

11. The Natal Field Force finally linked up with the South African Field Force in July 1900, but continued to exist as a separate formation until October when Sir Redvers Buller left South Africa. Major-General Henry John Thornton Hildyard (1846−1916) entered the Royal Navy in 1859, but transferred to the army in 1864. He had seen active service in the Egyptian expedition of 1882, commanded the staff college 1893 – 8, and commanded a brigade at Aldershot 1898 – 9. In April he was promoted Lieutenant-General and given command of a division. Amery, L.S. (gen. ed.) The Times History of the War in South Africa 1899 – 1902 Vol 2. London: Simpson, Low, Marston and Company Ltd, 1902 pp 113, 283 – 4

12. The battalions had suffered fairly heavy casualties in nine months fighting, especially at Colenso.

13. Riall, p 12, op cit.

14. Roberts, p 106, op cit.

15. Letter, Chamberlain to Otter, 21 Apr 1900, copy in my possession

16. Letter Bradshaw to Miss Kemp quoted in the Picton Gazette 10 Apr 1900, n.d. but probably early March; Letter Bradshaw to Thompson 16 Apr 1900 in Thompson file NAC

17. Militia Order 186 13 Aug 1900

18. This information is taken from a parchment scroll dated 24 Dec 1908 and signed by the Adjutant-General, Colonel F.L. Lessard that was presented to the Thompson family. A photo of the scroll is held by Mr. Douglas Cowden, a nephew of Private Thompson’s widow, who kindly allowed me to transcribe the details.

19. Address delivered by Mr. S.F. Thompson — Queen’s Scarf Ceremony 24 May 65

20. Another member of D Company, and one of the last Canadian survivors of the war, provided a taped interview to the CBC, probably during the early 1960’s. He stated that Thompson was living in Detroit when the war broke out and confirmed the details of Thompson’s actions on the 27th. CBC Radio “Ideas” transcript “Patriots, Scallywags and Saturday Night Soldiers” 25 Sep 91 p.8; Clipping from an unknown Ottawa newspaper dated 21 Feb 1900. The RCR Museum 14 – 401-1900-F

21. Newspaper clipping from Ottawa paper circa 19 Oct in NAC: Hare papers MG 29 E 25 reel M301.

22. Militia Order 203 15 Sep 1900

23. A short report of his visit, which describes him as ‘winner of the QS, ’ can be found in the Hare papers. For an example of a report of his selection see the Toronto Globe 25 Aug 1900.

24. This information appeared without citing a source in an article that appeared several years ago in a military collector’s newsletter. In the article the letter from Otter to Thompson is undated. In 1904 the Minister of Militia and Defence commented unfavourably to Otter that The RCR was the only Canadian fighting unit that served in the war that did not have a least one non-commissioned member receive a Victoria Cross or a Distinguished Conduct Medal. At the time non-commissioned members could be awarded either the Victoria Cross or the Distinguished Conduct Medal, or be mentioned in despatches. Not only did the medals, especially the VC, confer much more prestige than a mention in despatches, but recipients were eligible for an annuity. No such payment accompanied a mention in despatches … or the Queen’s Scarf, for that matter.

25. Roberts, p 106, op cit.

26. Fitchett, Ian. “The Queen’s Scarf,” in Sabretache, Journal of the Military History Society of Australia, Volume XVI, No 1 January 1974, pp 6 – 8. Wallace, R.L. The Australians at the Boer War. Canberra: The Australian War Memorial and The Australian Government Publishing Service, 1976

27. G.E. Buckle, ed., The Collected Letters of Queen Victoria, 3rd Series, Vol. III, 1896 – 1901. London: John Murray, 1932. p 582

28. My first hint that Chadwick was an American was provided by Douglas Cowden, whose file of Queen’s Scarf memorabilia included a note that Chadwick had helped cut the cable at Cienfuegos. The South African National Museum of Military History provided a copy of an article on Chadwick in Home Front magazine and a resume of Queen’s Scarf data compiled by Private Dufrayer’s son. The United States Navy archives sent me a copy of Chadwick’s citation for the Medal of Honor and a brief account of the battle. A more complete account of the action at Cienfuegos may be found in the June 1993 edition of Military History magazine. Stowers, Richard. Kiwi versus Boer, The First New Zealand Mounted Rifles in the Anglo-Boer War 1899 – 1902. Hamilton, NZ: privately published, 1992 p 79; NZ Army Secretary. Letter Army SA.96 21 July 1964 to Soldier magazine; Biographical Sketch Henry David Coutts 11 December 1968; Abbott, P.E. Recipients of the Distinguished Conduct Medal 1855 – 1909 London: J.B. Hayward and Son, 1975 p 43; Harfield, Alan. ‘Queen Victoria’s Scarves” in Military Collector & Historian Vol XLII No 3 Fall 1990 pp 104 – 7; Gallagher, Gerald J. ‘Hero of Eagle and Crown’ in Home Front, The MOTH Magazine, November 1985 p 4; Dufrayer, A.G.H. DISTRIBUTION OF THE QUEEN’S SCARF OF HONOUR, 1974; Anglesey, The Marques of. A History of the British Cavalry 1816 – 1919, Volume 4: 1899 – 1913. London: Leo Cooper, pp 156 – 161

29. Fitchett pp 5 – 6 op cit.; NZ Army Secretary op cit.; Honours and Awards pp 13, 24, 42, 43, 47, 82 – 7, 96, 99, 122 op cit.; Anon. Medal of Honor 1861 – 1949. Washington: Department of the Navy, n.d. p 73

30. The Summer 1964 edition of The Canadian Military Journal published a story about Thompson and his scarf which included the same information as the press release as well as a statement that the scarf ranked equally with the Victoria Cross. I believe, because of the wording, that the information for the article was provided by DND public affairs. The first reference to the alleged Australian Army Order was in “The World’s Rarest Award for Valour: Queen Victoria’s Scarf” in The Illustrated London News 23 Jun 56. Some authorities have suggested that the order originated with the Dufrayer family who have waged a decades-long campaign to have the scarves formally recognized as equivalent to the Victoria Cross. I have been unable to locate any material that would support or refute this assumption. Fitchett p 8 op cit.; Anon. ‘The Queen’s Scarf of Honour’ The Canadian Military Journal Vol. XXX No. 7−8−9, Summer 1964 p 29; Canadian Forces Press Release 9 Sep 64 pp 1 – 2

31. Fitchett p 6 op cit; NZ Army Secretary op cit.

32. Anon. The Canadian Almanac and Miscellaneous Directory for the Year 1903. Toronto: Copp, Clark Company, Limited. p 162. NZ Army Secretary op cit.; Fitchett pp 8 – 11 op cit.; Home Front p 4 op cit.

33. Riall p 12 op cit.; Fitchett pp 4, 6 op cit; NZ Army Secretary op cit; South African National Museum of Military History MUS 402÷3÷2 7 Jun 95

----------------------

William Hall, VC

William Hall was the first Black person, the first Nova Scotian and one of the first Canadians to receive the British Empire’s highest award for bravery, the Victoria Cross.The son of former American slaves, Hall was born in 1827 at Horton, Nova Scotia, where he also attended school. He grew up during the age of wooden ships, when many boys dreamed of travelling the world in sailing vessels. As a young man, Hall worked in shipyards at Hantsport for several years, building wooden ships for the merchant marine. He then joined the crew of a trading vessel and, before he was eighteen, had visited most of the world’s important ports.

Perhaps a search for adventure caused young William Hall to leave a career in the American merchant navy and enlist in the Royal Navy in Liverpool, England, in 1852. His first service, as Able Seaman with HMS Rodney, included two years in the Crimean War. Hall was a member of the naval brigade that landed from the fleet to assist ground forces manning heavy gun batteries, and he received British and Turkish medals for his work during this campaign.

After the Crimean War, Hall was assigned to the receiving ship HMS Victory at Portsmouth, England. He then joined the crew of HMS Shannon as Captain of the Foretop. It was his service with Shannon that led to the Victoria Cross.

Shannon, under Captain William Peel, was escorting troops to China, in readiness for expected conflict there, when mutiny broke out among the sepoys in India. Lord Elgin, former Governor General of Upper Canada and then Envoy Extrodinary to China, was asked to send troops to India. The rebel sepoy army had taken Delhi and Cawnpore, and a small British garrison at Lucknow was under siege. Elgin diverted troops to Calcutta and, as the situation in India worsened, Admiral Seymour also dispatched Shannon, Pearl and Sanspareil from Hong Kong to Calcutta. Captain Peel, several officers, and about 400 seamen and marines including William Hall, travelled by barge and on foot from Calcutta to Cawnpore, dragging eight-inch guns and twenty-four-pound howitzers.

Progress was slow with fighting all along the way. At Cawnpore the Shannon crew joined another relief force under Sir Colin Campbell (later to become Lieutenant-Governor of Nova Scotia) and began the historic march to Lucknow.