GLOSSARY: In support of ...

BLUEPETE'S HISTORY OF NOVA SCOTIA:

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | H | I | J | K | L | M | [HISTORY JUMP PAGE] | |

| N | O | P | Q | R | S | T | U | V | W | X | Y | Z |

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-A-

- Acadia, Population Levels of Old ...:

- Acadia, Transport Ships of the Acadian Deportation (1755):

- Admiralty Court: (Under Construction.)

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-B- - Bastion:

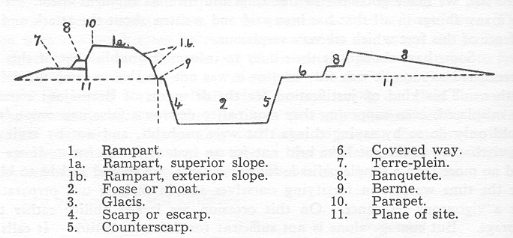

- A Bastion is a projecting part of a fortification, consisting of an earthwork, faced with brick or stone, or of a mass of masonry, in the form of an irregular pentagon, having its base in the main line, or at an angle, of the fortification; its flanks are the two sides which spring from the base, and are shorter than the faces or two sides which meet in the acute salient angle.

- Blendheim (1704):

- Boyne, Battle of the ...:

- [See Glorious Revolution.]

- Brigantine:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century..]

- Byng, John:

- [See Minorca.]

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-C- - Cape Finisterre:

- On May 14th, 1747, off the Atlantic coast of Spain, Cape Finisterre, a British fleet of 16 warships under Anson came upon a French supply fleet under escort; shortly thereafter, a very famous naval battle was to unfold leading to the surrender of the French admiral, La Jonquière; and, glory for Anson. Anson had with him, as second in command, Peter Warren, the naval hero of "The First Siege of Louisbourg (1745). Also present, as the captain of the 74 gun Namur, was Boscawen, who lead the English naval fleet during The Second Siege of Louisbourg (1758). La Jonquière was on his way to Quebec with many of those who had been deported to France by the English after the French surrendered Louisbourg in 1745. The French fleet consisted of 16 warships, 22 transports, and six East Indiamen. In the DCB, we see written that the odds were much in the favour of the English ("the French could line up only 312 guns against 978 for the British"; vol. iii, p. 610). I wonder about this; as the English and the French were matched as to the number of war ships. The French, notwithstanding they lost the battle, did carry out their duty and held all of their charges safe: the English did not get at the supply ships; they were able to get away and get to their destinations, unmolested. In any event, the English and the French men-of-war pounded away at one another for five hours. Jonquière's ship, the 64-gun Sérieux, had five English ships pouring tons of shot into her; 140 members of her crew were ether killed or wounded, indeed, Jonquière was wounded. In 1749, La Jonquière, incidently, after having spent two years in England as a prisoner of war, with the arrival of "peace," finally was to take up his gubernatorial duties at Quebec during the summer of 1749.

- Careen:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century..]

- Casemate:

- In a fortification, a vaulted chamber built in the thickness of the ramparts of a fortress, with embrasures for the defence of the place; a bomb-proof vault, generally under the ramparts of a fortress, used as a barrack, or a battery, or for both purposes.

- Le Chameau.

- Corvette:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century.]

- Covered Way:

- (See diagram under rampart.)

- Culloden.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-D- - Date:

- For the English, in 1752, there was a change in the way they dated things; it brought the country in to line with the dating system of other nations. I quote Trevelyan [England Under Queen Anne, vol. 2, preface, p. x.]: "Until 1752 the English at home always used the Old Style, after 1700 eleven days behind the New Style of Gregory XIII's Calendar, which was current in all continental countries except Russia. Our sailors, on service at sea and on coast operations like the taking of Gibraltar, generally used the Old Style familiar at home. Our soldiers in the Netherlands and Spain generally but not always used the New. Diplomats abroad most of them used the New, but some the Old." Further, it is to be noted that under the Old Style dating system, the new year started on March 25th and not January 1st. Most modern history writers, however, will use January 1st as the turn over for the new year.

- Dettington, Battle of ...:

- See note in the biographical write on Robert Monckton.

- Dysentery:

- "A disease characterized by inflammation of the mucous membrane and glands of the large intestine, accompanied with griping pains, and mucous and bloody evacuations." (OED.)

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-E- - Embrazure:

- An embrazure is much like a window or door through a wall. It is a gap or loophole, left open in a fortified wall so that a gun may be fired through it at the enemy outside of the walls. The sides of the embrazures, the jambs, are usually slanted or beveled, so that the inside profile of the opening is larger than that appearing on the outside of the wall. Such a spreading or embrasure of the jambs increases the opening inwards. An opening that leaves but just room for the muzzle to poke through and that widens as it comes in through the wall to the interior, allows a crew to work with the gun and yet leaves the least amount of exposure to the enemy beyond the walls.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-F- - Fascine:

- A long cylindrical faggot of brush or other small wood, firmly bound together at short intervals, used in filling up ditches, the construction of batteries, etc.

- Fighting Fortieth (1697-1762):

- Firkin:

- "A small cask for liquids, fish, butter, etc., originally containing a quarter of a barrel ..."

- Fontenoy, Battle of ...:

- See note in the biographical write on Robert Monckton.

- Flûte:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century..]

- Frigate:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century..]

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-G- - Glacis:

- A glacis is a gently sloping bank, which in fortifications, extends from the parapet of the covered way to meet the natural surface of the ground. (See diagram under rampart.)

- Gabion:

- A wicker basket, of cylindrical form, usually open at both ends, intended to be filled with earth, for use in fortification and engineering.

- Glorious Revolution (1688):

- Gordon Riots:

- The Gordon Riots were named after Lord Gordon Gordon (1751-93). At the age of 23, doubtlessly occupying a family seat, Lord Gordon was to become a Member of Parliament. His record apparently shows that he was quite ready to attack all sides. He was much against the political rehabilitation of Roman Catholics; though, there was a movement -- at long last -- to allow Catholics to come back into the political mainstream. In 1778, legislation was passed to restore certain political rights to Catholics. The response that Lord Gordon had was to go to the streets and work up the mobs. On June 2nd, 1780, a mob of 50,000 Londoners marched in procession to the House of Commons crying for repeal. A riot broke out which was to last five days during which time Catholic chapels and private homes were destroyed. Other houses of public officials were destroyed including the house of the Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield. On the 7th of June the troops were called out and 285 of the rioters were reportedly killed. Lord Gordon himself was tried for high treason, but he was to have a famous champion for a lawyer, Erskine, and, Gordon was acquitted. His acquittal was not to bring him any peace and I note that things, thereafter, were to go badly for him. In 1793, Lord Gordon died in prison (Newgate) having been put there on account of a libel on Marie Antoinette.

- Grenadiers

- Guns

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-H- - The Huguenot:

- Hogshead:

- A hogshead is a large cask for the storage and transportation of liquids and commodities. Abbreviated, hhd. Though its capacity did vary from country to country to one degree or another, the London hogshead of beer contained 54 gallons. Thus, the standard measure was around 50 gallons, for most liquids; but it could vary to a great degree, for example, a hogshead of molasses was, in 1749, fixed at 100 gallons. They were useful empty as well as full: Hogsheads fill'd with Earth served to make Breast-works, to cover the Men. "Innumerable fascines, and hogsheads, and trunks of trees, were heaped on each other." (Gibbon.) (See also pipe; for barrels, their sizes and use, see David E. Stephens' article, "Forgotten Trades of Nova Scotia" in NSHQ#2/1.)

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-I- - Immigrant Ships: The Arrrivals At Halifax, 1750-52:

- Indians:

- See The Micmac of Megumaagee.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-J- - Jacobites:

- Justices of the Peace:

- In the days under review, there was a distinct lack of legally trained people; yet, there was as great a need, as ever, for appointed individuals to adjudicate and to settle civil disputes. An upstanding member of the community would be appointed and charged with the duty to keep the peace in the area named. "Their principal duties consist in committing offenders to trial before a judge and jury when satisfied that there is a prima facie case against them, convicting and punishing summarily in minor causes, granting licenses, and acting, if County Justices, as judges at Quarter Sessions." (OED.) "Police work, petty justice, the poor law, and every function of local government" depended upon the justices of the peace. (Trevelyan's England Under Queen Anne vol. 1, p. 101.) Trevelyan, in another work of his, English Social History at p. 353, "... generally speaking the Justices who did most of the work in rural districts were substantial squires, too rich to be corrupt or mean, proud to do hard public work for no pay, anxious to stand well with their neighbours, but often ignorant and prejudiced without meaning to be unjust, and far too much a law unto themselves." With the passage of the County Council Act, 1888, the administrative functions of the Justices of the Peace were eliminated; rural magistracy came to an end in England. (Trevelyan's England Under Queen Anne, p. 100.) The system was followed in Canada in the old days; but, it no longer exists (pity).

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-K- -

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-L- - Letter of Marque:

- Letters of marque (and reprisal), a licence, would be granted to appropriate subjects by both sides in a time of war. It was "a licence to fit out an armed vessel and employ it in the capture of the merchant shipping belonging to the enemy's subjects, the holder of letters of marque being called a privateer or corsair, and entitled by international law to commit against the hostile nation acts which would otherwise have been condemned as piracy." (OED.)

- Louisbourg Fleet (British): 1745.

- Louisbourg Fleets: 1758.

- Louisbourg Regiments: 1758.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-M- - Malicite Indians: (See The Micmac of Megumaagee.)

- Men-of-War at Louisbourg, 1745:

- The Twelve British War Ships who participated in the First Siege Louisbourg.

- Micmac of Megumaagee:

- Minorca:

- In May of 1756, Admiral John Byng (1704-57) of the British navy failed to engage the French fleet at Minorca in the Mediterranean in a manner which might have been approved by the British Admiralty. Admiral, or no, Byng was brought back to England under arrest, court marshaled and found guilty. His sentence: he was brought down to Portsmouth and was ceremoniously shot dead on the quarter deck of one of his ships, the Monarque.

- Mississippi Joint Stock Company:

- On September 6, 1720, the formation of the Mississippi Joint Stock Company was entered into the registers at Paris, setting up "crazed speculation" in the streets of Paris for a period of five years when the whole fantastic scheme came tumbling down at considerable expense to the French, especially the forced, imprisoned, and famished settlers at the new French colony in Louisiana. This early and disastrous stock promotion came about as the result, not of a Frenchman, but of a man from Scotland, John Law (1671-1729). John Law was originally from Edinburgh, the son of a goldsmith and banker. He went to Paris and convinced the authorities that paper money was the answer to the French government's need to finance its royal spending habits. "In 1719, Law originated a joint stock-company for reclaiming and settling lands in the Mississippi valley, called the Mississippi scheme." (Chambers.) Law proposed and tried to set up "a prodigious system of credit, of which Louisiana, with its imaginary gold mines, was made the basis. The government used every means to keep up the stock of the Mississippi Company. It was ordered that the notes of the royal bank and all certificates of public debt should be accepted at par in payment for its shares. Powers and privileges were lavished on it. It was given the monopoly of the French slave-trade, the monopoly of tobacco, the profits of the royal mint, and the farming of the revenues of the kingdom. Ingots of gold, pretending to have come from the new Eldorado of Louisiana, were displayed in the shop-windows of Paris. The fever of speculation rose to madness, and the shares of the company were inflated to monstrous and insane proportions." (See Parkman, A Half Century of Conflict (vol. 1), pp. 315-6.)

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-N- - New Style Date:

- See Date.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-O- - Old Style Date:

- See Date.

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-P-- Parapet:

- A parapet is "a defence of earth or stone to cover troops from the enemy's observation and fire; in permanent works, a protection against shot, raised on the top of a wall or rampart; in field-works, a bank of earth high enough to screen the defenders and thick enough to resist any shot that is likely to be discharged against it. spec. a bank of earth in front of a military trench." (See diagram under rampart.)

- Pinnace:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century..]

- Pipe:

- A pipe is such a cask with its contents (wine, beer, cider, beef, fish, etc.), or as a measure of capacity, equivalent to half a tun, or 2 hogsheads, or 4 barrels. Like so many of the old measurement terms, there was no standard and it varied for different commodities; but, it was usually 105 imperial gallons.

- Population Levels of Old Acadia:

- Population Levels of Louisbourg:

- Press Gang:

- Prize Money:

- In times of war the British navy, its officers and men, had an extra inducement to take enemy ships and their cargo. Captured ships and their cargo would be brought to a port which had a Court of Admiralty where the matter would be judged and decreed that the ship and cargo were a prize of war and to be sold with the proceeds to be Droits of the Crown, or of the Admiralty; as such, it was to be all given over to those responsible for the capture. The money was "divided into eighths, of which three went to the captain, one to the commander-in-chief, one to the officers, one to the warrant officers, and two to the crew." This system of prize money was long in place and certainly covered the period with which we are concerned about, indeed it was in place for the British during the Second World War. (Oxford Companion to Ships & the Sea.)

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-Q- - Quintal:

- A weight of one hundred pounds; a hundred-weight (112 lbs.).

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-R- - Rampart:

- A mound of earth raised for the defence

of a place, capable of resisting cannon-shot, wide enough on the top for

the passage of troops, guns, etc., and usually surmounted by a stone

parapet.

- Rated War Ships:

- [See Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century..]

- Regiments, Louisbourg: 1758.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-S- - Sally:

- To issue suddenly from a place of defence or retreat in order to make an attack.

- Sallyport:

- An opening in a fortified place for the passage of troops when making a sally. Sallyports were not peculiar to land forts, for instance a sallyport could be found on each quarter of a fire-ship, out of which the officers and crew make their escape into the boats. Also, one entered into a three-decker through a sallyport. Usually sally ports were always locked up and only opened up by special permission.

- Sailing Vessels of the 18th Century:

- Scurvy:

- Smallpox:

- Souriquois Indians:

- See The Micmac of Megumaagee.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-T- - Tea:

- By 1720, great quantities of tea was making its way to the docks at London. "The China drink" had made its introduction to English tables as early as 1657. By 1720, tea was driving business in London and exploration abroad. With the general expansion of trade after 1713 the growth was more rapid. In Great Britain, we see, the annual import rose from 121,000 lbs. in 1715 to 238,000 lbs. in 1720. Tea was not near as popular in the milder climates of the southern European states. The French, nonetheless, got in on the profitable tea trade, mainly, I suggest, because, ever since 1689 the English customs duties on tea had been absurdly high. It would appear the French were illegally supplying the tea drinkers in Britain. Smuggling was a big business in the English Channel islands. In the early days most of the tea came from China, though we see that the French did establish plantations in the West Indians. It was to be 1839, before the 19th century tea trade with India took off.

- Tierce:

- "An old measure of capacity equivalent to one third of a pipe (usually 42 gallons old wine measure, but varying for different commodities: cf. pipe); also a cask or vessel holding this quantity, usually of wine, but also of various kinds of provisions or other goods (e.g. beef, pork, salmon, coffee, honey, sugar, tallow, tobacco); also such a cask with its contents." (OED)

- Tories (See under Whigs):

- Typhus:

- "An acute infectious fever, characterized by great prostration and a petechial eruption; chiefly occurring in crowded tenements, etc." (OED.) "Petechial eruption" is the eruption of petechia, or small red or purple spots in the skin caused by extravasation of blood. It has many names down through history, including: Camp Fever, Jail Fever, Hospital Fever, and Ship Fever. Typhus is believed to be spread by a parasitic insect, the typhus-louse.

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-U- -

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-V- -

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-W- - Whigs:

-

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-X- -

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-Y- -

(Click on letter to go to index.)

-Z-

http://www.blupete.com/Hist/Gloss/Glossary.htm

---------------------

-

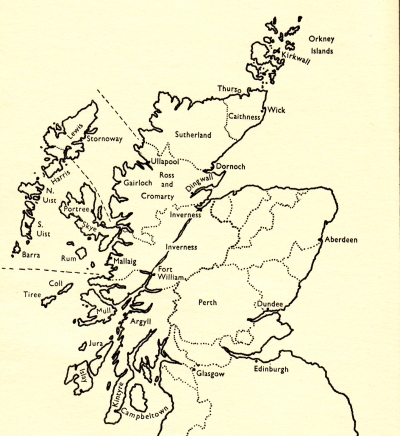

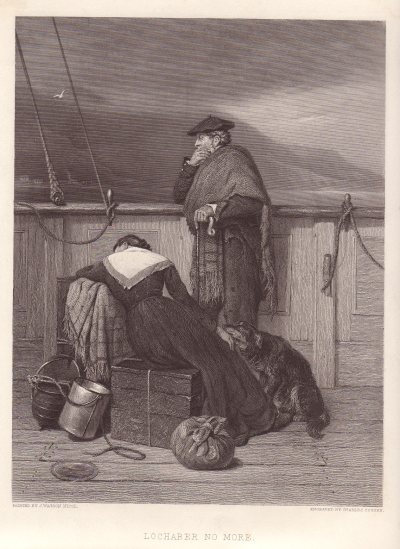

- "Scottish Immigration Into Nova Scotia"

"From the lone Shieling

of the misty island

of the misty island

Mountains divide us,

and the waste of seas --

and the waste of seas --

Yet still the blood is strong

the heart is Highland,

the heart is Highland,

And we in dreams

behold the Hebrides.1

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

GO TO TABLE OF CONTENTS.

behold the Hebrides.1

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

GO TO TABLE OF CONTENTS.

- Introduction

- The Highlander

- Post-Culloden

- Scottish Clearances

- Immigration To Nova Scotia

- Scottish Immigration To Cape Breton

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Authorities

[TOC]

Introduction The great English essayist, Macaulay wrote of them: "In perseverance, in self-command, in forethought, in all the virtues which conduce to success in life, the Scots have never been surpassed." Further, it might be said, that the Scots were a race in whom personal and family pride was the dominant passion. These attributes might well describe the Lowlanders and the Highlanders; though, there was a considerable difference of another kind between them, especially before the mid-18th century.2

Defoe described the Highlander:

"They are formidable fellows and I only wish Her Majesty had 25,000 of them in Spain [the British and the Spaniards were at war], as a nation equally proud and barbarous like themselves. They are all gentlemen, will take affront from no man, and insolent to the last degree. But certainly the absurdity is ridiculous to see a man in his mountain habit, armed with a broadsword, target, pistol, at his girdle a dagger, and staff, walking down the High Street as upright and haughty as if he were a lord, and withal driving a cow!"3

The Scots who came to Nova Scotia during the last half of the 18th and first half of the 19th century were Highlanders.4 They came to the shores of Nova Scotia, and, unlike many other immigrants that also came during this time, the Highlanders stuck and generally did not bleed away to other parts.5 Truly, Nova Scotia, especially that of Cape Britain, reminded the new arrivals of their native land, the Highlands of Scotland. They found the same looking land and soil; the same weather; and, in time, the same people (their brethren who had arrived earlier). It was not likely the only reason which drove families to relocate over the seas, but it is accepted that it was the land clearances in Scotland that drove the Highlanders to America. With the approval of those in the highest positions of government (then located in London) fences went up where fences had not been. Fences were needed to mark-off individual property rights; and these rights had finally come to Scotland ending the feudal system which had long lasted in Scotland. Prior to this "English" fencing there were, quite unlike what one sees today, no hedges; all about were open fields. These fields were cultivated, but strictly according to "village rules of immemorial antiquity." No one owned these common fields. Thus these fields, once available to the common people, were enclosed and large farms appeared. This process was part of a general revolution in society which had begun many years before in Europe and only lastly came to Scotland. The total effect of the unfolding process was likely, on the whole, good for Scotland.6

This process just briefly described, principally, led the Highlanders to immigrate to North America, with Nova Scotia getting, to her good fortune, more than her share of Highlanders.

[TOC]

The Highlander

The view had by the typical Englishmen of the Scottish highlander, a view, incidental, held by the mighty Roman army when it was in possession of most of the British Isles7 was expressed by the historian, G. M. Trevelyan:

"Beyond the Highland line ... lay the grim, unmapped, roadless mountains, the abode of the Celtic tribes, speaking another language; wearing another dress; living under a system of law and society a thousand years older than that of Southern Scotland; obedient neither to Kirk nor Queen, but to their own chiefs, clans, customs and superstitions. Till General Wade's work a generation later, there was no driving road through the Highlands. Nature reigned, gloomy, splendid, unchallenged ..."8

In 1724, the English decided that they would attempt to control these wild men to the north of them.9 They sent an army officer, George Wade to inspect Scotland. He reported back that what was needed was a permanent presence of the British Army. There should be forts and barracks built for British soldiers and to connect them up by proper roads. In the result, Wade was appointed as the commander for these northern regions and tasked with carrying out his own recommendations. Between 1725 and 1737 Wade directed the construction of some 250 miles of road and 40 bridges. This British military activity, worked. The Celtic tribes, their chiefs, clans, customs and superstitions, if not ended permanently, changed in 1745 with the Battle of Culloden.

"Although a fraction only of the clans had taken part in the last Jacobite Rebellion of 1745, all felt the results of its defeat. Bayonet and noose, the prescription of arms, of tartan and kilt, the abolition of the hereditary jurisdictions of the chiefs, the sequestration of their estates, began the destruction of the clan system. A memory survived, cocooned in the silk of songs, awaiting mutation in romance."10

The survived memory to which John Prebble referred was firmly in the minds of all highlanders and most certainly of those that came to the shores of New Scotland, Nova Scotia. [TOC]

Post-Culloden

After Culloden a distinctive era for Scotland came to an end and another began. It put an end to the claims of the Stuarts and it solidified the Hanoverian hold on the English throne. These were important objectives for those in power at the time, and the reason why the English troops under Cumberland did such a thorough job of it in northern Scotland. More important to history, is that in the aftermath of Culloden the clan structure of Scotland, which had been the last bastion of European feudalism came to an end. An entire new structure, of leadership and of law, was put in place which shook Scotland to its very roots.

To disperse the people of these Scottish clans became the objective of the English. A view became popular that it might be best if the Scottish rebels were shipped off to America. Admiral Peter Warren, in a dispatch to the Board of Trade dated July 10th, 1746, wrote: "Fones is just arrived here [Boston], and brings us the agreeable account of his royal highness' success [Culloden] against the rebels. I hope the government will hang every chief among them that can write or read, and send the rest to be dispersed through the American colonies!"11

More generally, hard times came to Great Britain in the wake of the Napoleonic wars (1793-1815). The lower classes became poverty stricken. The people who inhabited the Highlands of Scotland were always poor, in the years beyond 1815, more so. The authorities thought to relieve the developing problems by supporting schemes that would reduce population levels by shipping poor Scottish people to America. And so it came to be, that from 1815 to 1830 there was a steady stream of immigrants from Scotland many of whom came to Nova Scotia.

It is important to emphasize that the greatest number of Scottish immigrants came to Nova Scotia during the first half of the 19th century, in the wake of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815). In my work, Settlement, Revolution and War, I wrote of the earlier arrivals, especially those that arrived at Pictou on the Hector in 1773, the first ship to come to Nova Scotia directly from Scotland in the 18th century. The Hector was but one of a very limited number of immigration ships that arrived at Pictou in the 18th century. It is estimated that there may have been four, which is a number that pales to the number that arrived after the 19th century had begun.

The Scottish people who arrived on the Hector were Presbyterian from Sutherland (see map). They stayed on in the Pictou area joining the English speaking Protestants who had come from Pennsylvania in 1767. In the years after, the Scottish arrivals at Pictou settled in the area, but not all. If they were Presbyterian they tended to stick but the Catholics were encouraged to move on to Antigonish County and Cape Breton. Eventually, but not before 1802, Scottish settlers came directly from Scotland to Cape Breton.12 "Highland immigration to Cape Breton reached its peak in 1828, but it continued until the 1850s. Soon the Highlanders outnumbered all other ethnic groups in Cape Breton and both the eastern counties of Pictou and Antigonish."13

An analysis of the population levels in Cape Breton through the years 1817-1838, though no passenger lists survive, show that the Scottish Immigration was heavy.14 It appears that thousands of poor Scottish people came to the island. As of 1817, the population of Cape Breton was between 7,000 and 8,000; as of 1827 it was at 18,700; as of 1838 it was at around 38,000. The increase from 1817 to 1838 was approximately 30,000 mostly due to the influx of Highland Scots.15

The principal reason why these people were driven from their homelands, as the historians have labeled it, was because of the Scottish Clearances.

[TOC]

Scottish Clearances

It is not difficult to find people who will say it was the "Land Clearances" that drove the Highlanders from their ancient home grounds to Nova Scotia. This was likely part of why so many left their homes during this period, particularly between 1815 to 1830. Like so many phenomena that impact on human affairs, it is often difficult to point to causes that brought on a particular train of events. Certain of these causes can go back along time and are likely pinned to the culture of the people effected. This would be especially so, where a law is introduced, such as private property rights, to a land and culture which did not know of or depend upon such extensive rights.

"For the age of enclosure was also the age of new methods of draining, drilling, sowing, manuring, breeding and feeding cattle, making of roads, rebuilding of farm premises and a hundred other changes, all of them requiring capital."16 Trevelyan continues and points out that this movement started in the early part of the 18th century, much before Culloden, as the "rustic squires" with their smaller acreages gradually disappeared in favour of a growing landlord class who had the capital and credit for large agricultural operations.

Prior to the clearances, villages, a small collection of people, as were all villages of medieval times, were surrounded by open fields to be used by all and owned by the community as a whole. And so, between the years 1760 and 1840, "open fields" were abolished by acts of parliament and titles of ownership placed in the hands of a few who had won favour with the crown. Some good came of it; some bad.

"The inclosure movement had increased the amount of land in the hands of the upper and wealthy classes; the more enterprising small freeholders became large farmers, the weaker and poorer men sank into the status of labourers at a time when, owing to the increase in the rural population, there was already a drift of the labouring class into the towns. ... The labouring families, in areas of recent and considerable inclosure, lost their customary privileges of stubbling on open fields or putting a beast on the commons. The loss of fuel was also a hardship at a time when timber was scarce. ... The diet of most labouring families was bread and cheese for six out of seven days of the week, though some labourers kept a pig, and many had small gardens. It is difficult enough, on these low standards, to make any comparison with earlier times. On the whole, taking into account all sources of income, the average labourer was probably not worse off in the ten or twenty years after 1815 than he had been in 1790 ..."17

The "Clearances, no doubt, brought great changes to the way of life for the ancient Scottish clans. They were never quite farmers, nor fisherman: they were "semi-nomadic herdsmen." During the summer months the males would go off to mind their herds, leaving their cottages and families behind. Their herds would be cut back for the winter months with sales being made to the drovers.18 The sea did provide, however, some cash income. They gathered kelp along the shore, dried it, and burnt it for the resultant alkaline ash (potash) for which there was a great and growing demand during the late 18th century due to numerous manufacturing processes which were then being employed. For quite some period of time, "in Lewis and the Uists there were no songs sung about a land taken from the people, or of white-sailed ships taking away the best of the youth."19 The reason that Prebble gives, is, because the islands were profitable enough without sheep: they could harvest kelp from the sea. It is burnt for the sake of the substances found in the ashes. The calcined ashes of seaweed used in commerce for the sake of the carbonate of soda, iodine, and other substances which they contain; large quantities were formerly used in the manufacture of soap and glass. But mostly the ashes in the early part of the 19th c. in the Western Isles of Scotland were turned into a rich fertilizer. The kelp was burned over peat in great kilns on the shore. With the winding down of the Napoleonic Wars, the price for kelp ashes fell.20

Thus we have a reason, maybe the principal one, for the Highlanders leaving the Western Isles. The kelp industry failed. While places can be pointed out in the highlands of the mainland where the lairds cleared the land for sheep, the clearances did not much come to the Western Isles. The reason for this is that the majority of these Highlanders could no longer support themselves and their families on the collection and processing of kelp. Though still, the police came to boot the people out of certain of the communities, even if, as it turned out, they were not replaced by sheep. Cruel events occurred in the Western Isles though not as frequently or as extensively in the Mainland Highlands. John Prebble gave a couple of vivid descriptions of these events. The first is that which unfolded at Solas, North Uist, in 1849:

"The black flags of defiance were flying again the next morning when the police once more marched down the Lochmaddy road to Mallaglate. Now there was no discussion, no arguments, no appeals. The police formed two lines down the street of the township. Sheriff-Officers asked one question only at the doors of the cottages, whether those within were prepared to emigrate on the terms offered. If the answer was no, and it invariably was, then bedding, bed-frames, spinning-wheels, barrels, benches, tables and clothing were all dragged out and left at the door. Divots were torn from the roof, and the house timbers were pulled down ready for burning."21

Another example:"[A woman] with many tears, sobs and groans, put up a petition to the Sheriffs that they would leave the roof over part of her house where she had a loom with cloth in it which she was weaving ... [Another] woman, the eldest, made an attack with a stick on an officer, and missing her blow, sprung upon him and knocked off his hat. Two stout policemen had difficulty in carrying her to the door."22

Though it was all they had, it might well have been thought, by the burning of their abodes, that not much had been taken away from these poor people. Though conditions would not have improved by much when the Sheriffs went about their business a hundred years later: this is how a typical Highland home (black house) looked like in Queen Anne's time, 1702-14:"The style and material of building and the degree of poverty varied in different regions, but walls of turf or of unmortared stone, stopped with grass or straw, were very common; chimneys and glass windows were very rare; the floor was the bare ground; in many places the cattle lived at one end of the room, the people at the other, with no partition between. The family often sat on stones or heaps of turf round the fire of peat, whence the smoke made partial escape through a hole in the thatch overhead."23

[TOC]

Immigration To Nova Scotia Up to 1816, it cannot be concluded that there were any great numbers of ships coming to Nova Scotia with Scottish immigrants aboard. The Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) had put a damper on immigration in general. Thereafter, there is no lack of lists of immigration ships that came to Nova Scotia with Scots aboard; passenger lists, however, are another matter.24

A word about the sad scenes that played themselves out in Scotland as people left the only lands they ever knew to set out to lands across the sea.

"The sailing of an immigrant vessel was a deeply emotional experience, for those leaving and for those who remained. The Highlanders were like children, uninhibited in their feelings and wildly demonstrative in their grief. Men and women wept without constraint. They flung themselves on the earth they were leaving, clinging to it so fiercely that sailors had to prise them free and carry them bodily to the boats. A correspondent of the Inverness Courier watched the departure of some Kildonan people from Helmsdale: 'Hands were wrung and wrung again, bumbers of whisky tossed wildly off amidst cheers and shouts; the women were forced almost fainting into the boats; and the crowd upon the shore burst into a long, loud cheer. Again and again that cheer was raised and responded to from the boat, while bonnets were thrown into the air, handkerchiefs were waved, and last words of adieu shouted to the receding shore, while, high above all, the wild notes of the pipes were heard ...'"25

Martell estimated that 40,000 came to Nova Scotia as immigrants. In his preface to Martell's work, Harvey observed that there is an absence of specific returns of immigrants. Martell wrote: "Unlike many of the Pre-Loyalists and all or nearly all the Loyalists, the immigrants after 1815 who came to Nova Scotia from the British Isles were not, with a few exceptions, transported at the expense of the Imperial or Provincial government, land companies, or interested individuals.26 They received no implements or utensils to start them off, no regular rations to carry them over the first hard year or more, and no land laid out free of charge."27 Many of the poor Scots who arrived were obliged to pay for their passage and to fend for themselves in the uncleared forests. Charles W. Dunn:

"Life for him [the settler] was something more than a ceaseless round of cutting, burning, ploughing, planting, sowing, and reaping; and for his wife, something more than a grim monotony of cooking, carding, spinning, weaving, knitting, sewing, and mending. Their long hours of toil and their few well-deserved moments of leisure were always the occasion for laughter and story and song and music."28

Next, James Hunter:"... the many people here [Sydney] whose roots are in the Highlands have had an exceptionally raw deal from history. For a single family to have laboured in the kelp industry, to have been evicted from a croft, to have made the ocean crossing in an immigrant ship, to have hacked a farm out of virgin forest, to have found it impossible to make a living on that farm, to have gone into coal-mining, to have endured that industry's grim casualty toll and to have seen, at the end of all of this, the mines shut down is, whatever way you look at it, to have endured an awful lot in the space of half a dozen generations."29

The system of granting land -- at least in Cape Breton up to 1820 -- "was a source of much dissatisfaction."30 With the arrival of James Kempt, in 1820, as the newly appointed Royal Governor of Nova Scotia, things were in for a change. Within four months of his arrival in Nova Scotia, Kempt made a tour of Cape Breton."One of his first acts was to issue a code of instructions to the Surveyor-General, to lay off lands in lots of 100 acres to single, and of 200 acres to married men, with permission to occupy them under tickets of location until they were prepared to pay for grants, with the proviso, that no absolute title should be given except to bona fide settlers who had actually made improvements."31

The problem -- of obtaining good title to their lands -- for the Scottish immigrants continued for most of the first half of the 19th century, though there were attempts to alleviate the problem."In 1841 ... Lieutenant-Governor Falkland informed the Colonial Office that he had dispensed with public auction in Cape Breton and allowed settlers to occupy crown lands on the payment of a fixed price of 2s.6d. an acre. This modification might have appeared advantageous to the lieutenant-governor, but Surveyor-General Crawley soon pointed out that the intended purchasers consisted of 1,500 poor souls from the Hebrides, who possessed neither the power nor the inclination to avail themselves of Falkland's kind offer. Indeed, the majority had at once settled themselves on one of the larger grants of the absentees. Admittedly, two or three of these immigrants made enquiries at the land office, but they had frankly admitted that their intention was not to purchase crown land but to ascertain where vacant land could be found so that they could settle on it without purchase or permission."32

[TOC]

Scottish Immigration To Cape Breton For a variety of reasons, Cape Breton was slow to make itself ready to accept new immigrants, of any kind.33 More generally, it might be stated that during the war years (1793-1815) no one risked voyages at sea unless made in the company of a British Man-of-War. There was a short respite period when in 1802, the Treaty of Amiens was signed; the period lasted but eighteen months. Enough time, however, to set immigrant ships in motion from Scotland to America. During August of 1802, the first boat load of Scottish immigrants, 299, arrived at Spanish Bay (Sydney).34 We should note that it was in 1803 that Selkirk35 landed immigrants from the Scottish highlands at Prince Edward Island.36 Many of those that were first landed in Prince Edward Island, left to join their cousins who had been, by then, reasonably well settled in the Pictou area. With the Napoleonic Wars under way again, few Scottish immigrant ships came to Nova Scotia, until 1817, that is two years after the war had ended.

I suspect that the authorities kept track of the immigrant Ships that came into Pictou more so than those that landed at Cape Breton:

"Nor did these people's troubles end with the Atlantic crossing. Because Cape Breton was the earliest landfall made by ships heading ultimately for St Lawrence and Quebec, aspiring immigrants could get here more economically than they could travel to any other part of North America. And because Cape Breton's coastline, rather like that of the Scottish Highlands, is replete with sheltered coves and inlets, it was possible for those less scrupulous skippers who were common in the timber trade to put their passengers ashore in remote and unregulated harbours in order to avoid the delays and complexities which would have been encountered at more formal ports of entry to North America. 'Several vessels arrive annually and land their passengers on the western shore of this island,' customs officers complained from Sydney, 'the masters neglecting to make any report of the number.'"37

In 1817 there arrived two ships at Sydney, the Hope and the William Tell, both from Barra with 382 people aboard.38 That is all I can tell about these two vessels. Passenger lists for the two do not exist as is the case for most all the Scottish immigrant ships, though there has been some attempt to reconstruct them. The greatest number of Scottish immigrant ships came in following 1820 and carried on in reasonably steady numbers through to the middle of the 19th century. It is no coincidence, I should think, that beginning in 1820, a new official position in regards Cape Breton became evident. As we have already pointed out, in October of that year, the newly appointed the Royal Governor of Nova Scotia, Sir James Kempt, within four months of his arrival in Nova Scotia, made a tour of Cape Breton. On the 9th he declared that Cape Breton, which had been an independent British colony since 1784, was to be re-annexed to Nova Scotia as one of its counties. This brought in its train changes in the justice system.39 This was important for any commercial development of the island, as people with capital need the protection of the law, especially a registry system in respect to real property.

Moorsom, who made his observations in 1827, estimated the population of Nova Scotia, including Cape Breton, at 143,000. He estimated that of this only 600 were Indian and 1,500 were black. A doubling, Moorsom concluded, of the 1817 population of 72,000. While the information we have is shaky in regards to which ships came in from Scotland with immigrants aboard, we have as a practical matter no information who these Scottish people were and where they went to build their little huts and start life anew. Though, we do know, that these Scottish settlers flooded in and were in a destitute condition for a period of time.

James Hunter:

"... the town's magistrates noted in 1828, upwards of 2,100 persons have come into this district [Cape Breton] from the western part of Scotland many of whom, on their landing, were quite destitute of food and also of the means of procuring it. Sydney was again thought to be at risk from smallpox. And great numbers of newly disembarked Highlanders had been reduced to begging from door to door."40

In 1830, the "Surveyor General Crawley informed the Provincial Secretary that Cape Breton was 'threatened with a dreadful inundation from Scotland amounting to 3,000 souls,' and suggested that lots should be laid out for them in advance, to which they might repair at once, 'instead of lying about our beaches to be consumed by want and sickness."41 The question becomes -- What were the reasons for coming to Nova Scotia. Professor Bumsted put his finger on one of the reason, a surprising reason, given Culloden."Ironically enough, in view of their earlier treatment by the British, Highlanders were extremely loyal to King and Country in the American colonies, and they were much persecuted during the war as Tories or Loyalists. Many recently-emigrated Highlanders ended up fighting against the Americans in Loyalist or British regiments, then being disbanded and receiving land in the provinces of British North America which remained within the Empire after the débâcle. Highlanders had always been more inclined than Lowlanders to emigrate to the wilderness colonies of Nova Scotia, the Island of St John, and Canada, and with peace they were joined by many of their fellow Highlanders who had initially sought a place in the rebellious American colonies to the south."42

Abraham Gesner, the discover of Kerosene, a native son of Nova Scotia, said this of the Scottish settler:"Perhaps there are no race of people better adapted to the climate of North America [Cape Breton] than that of the Highlands of Scotland. The habits, employments, and customs of the Highlander seem to fit him for the American forest, which he penetrates without feeling the gloom and melancholy experienced by those who have been brought up in towns and amidst the fertile fields of highly cultivated districts. Scotch immigrants are hardy, industrious, and cheerful, and experience has fully proved that no people meet the first difficulties of settling wild lands with greater patience and fortitude."43

Most all of these Highlanders eventually made homes for themselves, and things soon settled down into a comfortable rural routine in a number of areas in Cape Breton. This routine was nicely described by Charles W. Dunn:"As the spring moves grudgingly along there is always plenty of work for the men-folk to do. The farmer gets his equipment ready for planting. The fisherman overhauls his boat and engine, and mends his nets, or completes his lobster traps. Both fisherman and farmer inspect their fences and put in new posts and poles wherever they are needed. The cows calf; the mares foal; the sheep lamb; the hens are set on their eggs, and hatch out their chicks, and the household cat proudly summons her new kittens out from the barn.

[TOC]

Then the busy season begins. The fisherman leaves his house and takes up his residence at the shore, immersing himself in a tangle of rope, lines, crates, kegs, barrels, nets, traps, hooks, and buckets. In a short he is out to sea, setting the traps and nets, trying to guess where the fish will run this season. From then on through the summer he is never idle. Each kind of fish requires special gear and a special technique -- salmon, herring, mackerel, cod, lobster -- and all require incessant watchfulness and toil.

The farmer, at the same, is trying to foresee what nature is going to bring him in the way of weather. He begins to plough and harrow and sow and plant. Summer moves on. The seeds entrusted to the soil thrust out green blades. Finally the season brought home. The tempo of life slows down. The people are secure for another year. Whatever may befall, they will have plenty to eat. ....

In winter when it is impossible to get to a store the wise farmer or fisherman has a well-stocked house. Even in an isolated settlement at this time of the year it is not uncommon to find in a fisherman's house fresh eggs, milk, cream, and butter; half a carcass of beef hanging frozen in the out-house; a barrelful of home-killed pork, and cuts of home-cured ham and bacon; a hundred-pound box of dry-salt-cod, a barrel of salt herring; miscellaneous frozen fish recently caught, such as cod, skate, and ells; home-canned fruit; and a store of other necessities purchased in the autumn."44

Conclusion The adversities faced by the pioneers that came to Nova Scotia convinced a number, after a winter season or two, to go south into the lands of promise and plenty, the United States, with a climate not to be found in Nova Scotia. But the Scots -- well, they were use to the climate of Nova Scotia before they even set a foot on its soil. The hard times experienced by the Highlanders only served to enhanced the ingrained character of a Scottish person:

"All the perplexity and doggedness of the race was in him, its loneliness, tenderness and affection, its deceptive vitality, its quick flashes of violence, its dog-whistle sensitivity to sounds to which Anglo-Saxons are stone deaf, its incapacity to tell its heart to foreigners save in terms foreigners do not comprehend, its resigned indifference to whether they comprehend or not. It's not easy being Scotch, he told me once. To which I suppose another Scotchman might say, It wasn't meant to be."45

In Scott's Fair maid of Perth there is a scene in chapter viii where one of the characters introduces himself:"My name is the Devil's Dick of Hellgarth, well known in Annandale for a gentle Johnstone. I follow the stout Laird of Wamphray, who rides with his kinsman, the redoubted Lord of Johnstone, who is banded with the doughty earl of Douglas; and the Earl, and the Lord, and the laird, and I, the esquire, fly our hawks where we find our game, and ask no man whose ground we ride over."

It was these freedom loving persons, these people of the Scottish Highlands who came to Nova Scotia in considerable numbers during the first half of the 19th century. The succeeding generations mixed in to the existing populations that had earlier come to Nova Scotia: the French, the English and the German and thus was formed the unique strain of individuals that call themselves Nova Scotians.

-- End

-- End

_______________________________

Authorities

Ashton, T. S., An Economic History of England: The 18th Century (London: Methuen, 1955)

Brown, A History of the Island of Cape Breton (1869) (Belleville: Mika, 1979)

Bumsted, The People's Clearance: Highland Emigration to British North America: 1770-1815, (University of Manitoba Press, 1982)

Burroughs, "The Administration of Crown Lands in Nova Scotia, 1827-1848," NSHS, #35

Collier, The Crofting Problem, (Cambridge University Press, 1953)

Dunn, Highland Settler: A Portrait of the Scottish Gael in Nova Scotia, (University of Toronto, 1953)

Ells, Calendar of Official Correspondence and Legislative Papers Nova Scotia, 1802-1815; compiled by, Pub. #3 (Halifax: PANS, 1936)

Harvey, "Scottish Immigration to Cape Breton," Dalhousie Review, Vol. 21 (1941)

Hill, The Scots to Canada (London: Gentry Books, 1972)

Hunter, A Dance Called America (1994) (Mainstream Publishing, 1998)

Johnson, The Birth of the Modern, (New York: HarperCollins, 1991)

Macdonald, The Last Siege of Louisbourg (London: Printed for the Author by Cassell & Co., 1907)

Martell, Immigration To And Emigration From Nova Scotia: 1815-1838, (Halifax: PANS, Publication No. #6, 1941)

Prebble, The Highland Clearances, (1963) (Penguin)

Savary's supplement, History of the County of Annapolis (1913), (Belleville: Mika, 1973)

Trevelyan, G. M., England Under Queen Anne: 1702-1714 (1930, 1932, 1934), (London: Longmans, Green; 1948)

--, English Social History (Toronto: Longmans, Green; 1st Can ed., 1946)

Navy Records Society, The Royal Navy and North America (London: Vol. 118, 1973)

Woodward, The Age of Reform: 1815-1870 (1938)(Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2nd ed., 1962)

_______________________________

---------------

HISTORY OF NOVA SCOTIA=-

This jump off page will lead one into things historical.- NOVA SCOTIA

"The Micmac of Megumaagee"

"Unfortunately for the Indians, their enemies have

been their only historians; the records of their cruelties remain, but the

wrongs which provoked them are either untold, or are ignored and

forgotten." (Hannay,

p. 51.)

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

GO TO TABLE OF

CONTENTS.

>>>>>>>>>>

A Selection of Micmac Words

<<<<<<<<<<

|

|||

Let us look in on a scene as described by Elizabeth Frame:

"Here some of the women were busy sewing new and

repairing old birch-bark canoes. In this primitive ship-yard neither broad-axe

nor caulking-mallet was required. The framework was made of split ash, shaped

with a knife and moulded by hand; this was covered with sheets of white

birch-bark, sewed round the wood-work with the tough root-lets of trees. The

wigwams were formed of poles stuck into the ground and secured at the top by a

withe.1 This

circular inclosure was covered with birch-bark; a blanket or skin covered the

aperture which served for a door; and the centre was occupied by the fire, the

struggling smoke of which found its way out at the top. Round the fire, boughs

were laid, which served the family for seats. Dogs snored around the camps, and

papooses lay sleeping in the cradles strapped to their mothers' backs, their

brown faces upturned to the sun. One mother sat apart, nursing a dying babe.

She had prepared a tiny carrying belt, a little pail, and a paddle, to aid her

child in the spirit land. Beside the spring some women were preparing the feast

for the congregated warriors. Over the fire were suspended cauldrons containing

a savory stew of porcupine, caribou, and duck. Salmon were roasting before the

fires, the fish being inserted, wedge fashion, into a split piece of ash some

two feet in length, crossed by other splits, its end planted firmly into the

earth at a convenient distance from the fire."2

Who were these people? They were northern Indians who

have long occupied the forests of the northeastern parts of the North American

continent.

"They were a typical

migratory people who lived in the woods during the winter months, hunting

moose, caribou and porcupine. In the spring they moved down to the seashore

where they gathered shellfish, fished at the mouths of rivers and hunted the

coastal seals. Like most Algonquin

tribes, they lived in conical wigwams covered with birch bark while making

canoes and household utensils from the same material. They also made cooking

pots from clay and large wooden troughs in which they boiled their food by

dropping stones, heated by the fire, into the water. Their weapons were stone3 tomahawks,

stone knives, bows and arrows and spears with two edged blades of moose bone or

other animals bones."4

George MacLaren was writing of the original

natives of a land which I refer to as Old Acadia; but which the natives at the

time referred to as Megumaagee.

They were stone age people, who, in their original state, were only but briefly

sighted when the earliest of the European explorers came to the shores of an

area which we now call the Canadian Maritime Provinces. What was had was but a

glimpse of a people who were to be divested by the glimpsers. The fact of the

matter is that within a generation, the Micmac were hurtled into a new age. So,

therefore, what was to be recorded (a new age activity) and handed down to us:

are but indistinct images, reflections and shadows of a people whose culture

and traditions we shall never know in their true form, being, as they were,

obliterated by European influences. The Micmac, their beliefs, their

traditions, were all to change because of the processes of acculturation and

miscegenation.5

[TOP][TOC]

The Origins of the Micmac

The ancestors of the Micmac -- like the ancestors of all of us who currently occupy the Americas -- came to occupy their traditional home lands through immigration. As to the time and manner of the immigration: it is, but speculation. The best thinking, it seems, is that the Palaeo Indians came into the area we now know as Nova Scotia some 11,000 years ago. They were but a branch of the original immigrants to the Americas: all came over from Asia via Siberia and slowly, in their nomadic fashion, spread south and east. Actually, it is thought,6 that these original people either died off or further immigrated. The Micmac people, likely lived further south before they came into the lands of our larger story, Acadia -- the ocean shores, from Gaspé to Cape Sable.7 There had been, as may be determined from the writings of the early explorers, a rather dramatic shift of the north American tribes, certainly for those in the northeast quarter of North America. This, likely, due to the ferociousness of the Iroquois. The ancestral home of the Iroquois was in an area now identified as upstate New York, the Mohawk River and the Finger Lakes. The influence of the Iroquois spread, directly and indirectly, across great distances. The Micmac, though they could make as great a show as any nation, were of a milder and retiring spirit; they were, as a consequence, under great pressure from their fiercer southern neighbors. It would appear at the time Acadia was first established, circa 1600, the Micmac were being pushed to the northeastern extremities of the continent.

[TOP]

[TOC]

Population Levels

Paul Mascarene reported,8 in 1720, that "the Indians are but a handful in this country."9 The estimates of the Micmac population varied widely. 10 A census of 1687-8 discloses that there were then 925 Indians in territories that now form part of Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.11 One count in 1721 was 289 and another, in 1722, 838. 12 In 1739, the Indian population was estimated: 200 braves in Acadia, 80 in Cape Breton, 195 at Miramichi and 60 at Restigouche.13 (Miramichi and Restigouche are to be located in the present day province of New Brunswick.) Further, in 1739, a memorandum to Isaac Louis de Forant, one made in order to acquaint him with his new post as the new governor of Ile Royal, set forth a number of 1,200. This number covered the principal encampments of the Micmac which we see listed in the report: Miragouëche, Port-Royal, La Heve, Cape Sable, Miramichi, and Restigouche.14 Thus, as we can see these numbers vary, and do not, in any event, include the Malecites of the St. John. I should say, that the first reliable number that we have is that which was struck as a result of the census of 1871: the Micmac of Nova Scotia at that time numbered 1,666.15

The above accounts were those made only after the arrival of the Europeans. As to the Micmac population before then? Well, James Hannay, one of our most reliable historians of the era, was of the view that the total population never likely exceeded 3,000. This conclusion is not hard to accept if one remembers that the original natives, as found, were "hunter gatherers." As Hannay points out: "An uncultivated country can only support a limited population. The hunter must draw his sustenance from a very wide range of territory ..."16

[TOP]

[TOC]

Spiritual Beliefs

"Their primitive religion is obscure. They

recognized a Great Spirit, or even several Great Spirits, whom they called

Manitous - in Micmac Mento or Minto (pronounced Mendoo) [see Manitou]

- and they had no other personal divinities. Interiorly they feared Manitou and

revered and adored him, while exteriorly they offered him sacrifices and made

him part of their sorcery, seeking to render him favourable, or rather to

prevent his harming or hindering them in their various enterprises. From the

time of their forefathers, they said, Manitou had kept plaguing them. They did

not look upon him as all-powerful or benevolent, nor did they speak of him as

their creator. There is no evidence that they believed in any sort of

creation."17

The Micmac, in a Spinozistic

sense, certainly did believe in creation; and, did believe and recognized a

higher power as having control of their destiny, a power that was entitled to

reverence. These beliefs, indeed, was one of the distinguishing features of the

North American Indian. Their general mental and moral attitude was totally

shaped by their belief in nature, as God. They had no need, nor did they

organize themselves into religious groups with rules and rulers, however, the

European missionaries were only too keen to introduce the notion of organized

religion: all the better, for the purposes of control. Lescarbot,

based on his personal observations, quotes, with approval, his fellow

countryman and explorer, Jacques Cartier, who had been in the territory 65

years earlier, between 1535 and 1541:

"They believe also

that when they die they go up into the stars, and afterwards they go into fair

green fields, full of fair trees, flowers, and rare fruits. After they had made

us to understand these things, we showed them their error, and that their

Cudouagni is an evil spirit that deceiveth them, and that there is but one God,

which is in Heaven, who doth give unto us all, and is Creator of all things,

and that in him we must only believe, and that they must be baptized, or go

into hell. And many other things of our faith were showed them, which they

easily believed, and called their Cudouagni, Agoiuda."18 (Lescarbot.)

"A dog was regarded

as the most valuable sacrifice, and if, in crossing a lake, their canoe was in

danger of being overwhelmed by the winds and waves a dog was thrown overboard,

with its fore paws tied together, to satisfy the hunger of the angry Manitou.

They were continually on the watch for omens, and easily deterred from any

enterprise by a sign which they regarded as unfavourable. A hunter would turn

back from the most promising expedition at the cry of some wild animal which he

thought was an omen of failure in the chase."19

The spirits in which the Micmac belief were not all "vague and

indefinite"; indeed, some were distinct and identifiable. The one that

readily comes to mind is Glooskap. Glooskap was the chief spirit of the Micmac:

he had a myriad of lesser spirits that attended upon him: he created man from

the heart of the ash tree. The names of all the birds and animals were long ago

named by Glooskap. Glooskap, it was said, would ride on the backs of the whales

and the loons were his willing messengers.

"While he roamed the province incessantly, encamping

in many different spots, his chief abiding place was the crest of Blomidon.

Before his time the beavers, who were then huge, powerful beasts, had built a

great dam across the strait from Blomidon to the Cumberland shore, thus making

Minas Basin an immense pond or inland sea. One day by speaking a word or by

waving his wand, Glooscap broke the beaver dam and let the fierce Fundy tides

rush in, as they have ever since continued to do. Towards a beaver who was in

hiding near, and whom the demigod wanted to frighten, he once tossed a few

handfuls of earth. These lodging a little to the eastward of Parrsborough

became Five Islands."20

Champlain,

as most of these religious Frenchman were, was perplexed because he could not

observe any outward manifestations of the Indian worship of nature:

"I demanded of him what ceremony they used in

praying to their God: he told me that they used no other ceremony but that

everyone did pray in his heart as he would. This is the cause why, I believe,

there is no law among them, neither do they know what it is to worship or pray

to God, and live the most part as brute beasts; and I believe that in short

time they might be brought to be good Christians, if one would inhabit their

land, which most of them do desire. They have among them some savages whom they

call Pilotoua, who speak visibly to the devil, and the telleth them what they

must do, as well for wars as for other things; and if he should command them to

go and put any enterprise in execution, or to kill a Frenchman or any other of

their nation, they will immediately obey to his command. They believe also that

all their dreams are true; and, indeed, there be many of them which do say that

they have seen and dreamed things that do happen or shall come to pass; but to

speak thereof in truth they be visions of the Devil, who doth deceive and

seduce them."21

The work of the missionary in converting the natives, was,

apparently, not too difficult, as Lescarbot observed:

"These people (as

one may say) have nothing of all that, for it is not to be called covered, to

be always wandering and lodged under four stakes, and to have a skin upon their

back; neither do I call eating and living, to eat all at once and starve the

next day, not providing for the next day.22 Whosoever

then shall give bread and clothing to these people, the same shall be, as it

were, their God: they will believe all that he shall say to them ... These

people then enjoying the fruits of the use of trades and tillage of the ground

will believe all that shall be told them, in auditum auris, at the first voice

that shall sound in their ears; ... [an example of the chief of the St. John

Indians] he eateth, lifteth up his eyes to heaven and maketh the sign of the

Cross, because he hath seen us do so: yea, at our prayers he did kneel down as

we did. And because he hath seen a great Cross planted near to our fort, he

hath made the like at his house, and in all his cabins; and carrieth one at his

breast ...."23

(Lescarbot.)

In any event, it seems that the North American natives

were predisposed to adapting the European religion. There was a myth handed

down from the generations past that all powerful white Gods would come from the

east to teach and show them the way to a glorious future. The Irish novelist,

Eliot Warburton in his preface to his brother's, George

Warburton's work, Hochelaga (1846) made reference to this feeling that ran

among the natives:

"Strange to say, this prophetic feeling [the east

overcomes the west] was responded to by the inhabitants of the unknown world:

among the wild and stern Mic-Macs of the North, and the refined and gentle

Yncas of the South, a presentiment of their coming fate was felt. They believed

that a powerful race of men were to come 'from the rising sun,' to conquer and

possess their lands."

"They [the Micmacs]

were distinguished for their honesty. They were still more distinguished for

their chastity. There is no instance on record of any insult being offered to a

female captive by any of the Eastern Indians, however cruelly she might

otherwise have been treated."24

The rulers (to the extent there were any) were male.25 The

successful hunters, the providers of food for the family, the extended family,

the tribe, were always to be given general preference and respect. The best of

them was the chief. The chiefs were semi-hereditary.26 Though the

sons of a chief always had the edge, any brave warrior/hunter could become a

chief; continual success in the hunt or when fighting enemies would bring a

young man to the top of his tribe.[TOP]

[TOC]

The Medicine Man

The Medicine man, not one who was necessarily a good hunter or warrior, was also much respected and regularly consulted before the tribe struck out on any sort of an adventure. He was a special man who had proved himself as being able to call on the spirits, predict the future and thereby able to steer the tribe in the right direction.

"If anyone be sick, he [well decked out with maracas

or rattles, and feathers] is sent for; he maketh invocations on his devil; he

bloweth upon the part grieved; he maketh incisions, sucketh the bad blood from

it: if it be a wound, he healeth it by the same means, applying a round slice

of the beaver's stones. Finally some present is made unto him, either of

venison or skins. If it be question to have news of things absent, having first

questioned with his spirit, he rendereth his oracles ...."27 (Lescarbot.)

"So implicit was the belief in the medicine-man that when he

pronounced a disease or a wound fatal, the patient ceased eating, and was given

nothing more; he put on a fine robe and chanted his death-song.28 To hasten

his end, the onlookers would throw cold water over him, or sometimes bury him

half alive."29

(Diereville.) First thing that was to be done upon the death of an individual is for the family and the tribe to have a feast, one that continued for a couple of days during which numerous orations were pronounced.

"On the third day a feast was held as a recognition

of the great satisfaction which the deceased was supposed to feel at rejoining

his ancestors. After this the women made a garment, or winding sheet, of birch

bark, in which he was wrapped and put away on a sort of scaffold for twelve

months to dry. At the end of that time the body was buried in a grave, in which

the relatives at the same time threw bows, arrows, snow-shoes, darts, robes,

axes, pots, moccasins and skins."30

Lescarbot gives an accounting of the funeral ceremonies

of a respected member of the tribe, one, Panoniac. Panoniac had traveled south

down the coast, likely to the Cape Cod area, there to trade with their old

enemy, the Armouchiquois. Panoniac, unfortunately, got the bad end of a bargain

and was killed or badly wounded such that he eventually died. Panoniac, or his

body was brought back up the coast. Lescarbot made the following observations:

"After our savages

had wept for Panoniac, they went to the place where his cabin was whilst he did

live, and there they did burn all that he had left, his bows, arrows, quivers,

his beavers' skins, his tobacco (without which they cannot live), his dogs31, and other

his small movables, to the end that no body should quarrel for his

succession."32

(Lescarbot.)

The natives apparently did bury Panoniac, in the spring, just before

getting a war party together so to go to revenge his death. They dug Panoniac

up and transported his remains to "a desolate island, towards Cap de

Sable, some five-and-twenty or thirty leagues distant from Port Royal. Those

isles which do serve them for churchyards are secret amongst them, for fear some

enemy should seek to torment the bones of their dead."33 Further,

"after they have brought the dead to his rest, every

one maketh him a present of the best thing he hath. Some do cover him with many

skins of beavers, of otters, and other beasts; others present him with bows,

arrows, quivers, knives, matachias, and other things."34 (Lescarbot.)

Into the Grave they put

a living Dog,

Hatchet and Corn, a blanket and a Pipe,

Tobacco, Powder, Lead and Pot, Canoe

And musket for they think that he who dies

Will make a Journey of great length

And will have need of all this Gear

For clothing and for nourishment.35 (Diereville.)

The Micmacs, though a wary lot, were

described by the first Jesuit missionaries as "mild and peaceful in

temperament."36 They,

certainly, were often men of few words. Lescarbot

recounts he saw many times how a total stranger would arrive at an encampment

of Micmacs set up outside the walls of the habitation at Port Royal. The

stranger would somehow know which hut to enter, the hut of the chief, Membertou.

The stranger would immediately sit down, take out his pouch of tobacco, fill

and light his pipe, take a number of hauls on the stem and then "did give

the tobacco-pipe to him that seemed to be the worthiest person, and after

consequently to the others. Then some half an hour after they did begin to

speak."Hatchet and Corn, a blanket and a Pipe,

Tobacco, Powder, Lead and Pot, Canoe

And musket for they think that he who dies

Will make a Journey of great length

And will have need of all this Gear

For clothing and for nourishment.35 (Diereville.)

The Micmac, as it seems with all the North American natives were very sociable. They would interact freely amongst themselves and were very hospitable even to strangers who might come among them. They would readily share their food and their tobacco and invite them, for example, into their sweat hut.37

As for a sweat hut, or pit: Lescarbot describes one38: they "dig in the ground, and make a pit which they cover with wood and big flat stones over it; then they put fire to it by a hole, and, the wood being burned, they make a raft with poles, which they cover with all the skins and other coverings which they have, so as no air entereth therein; they cast water on the said stones, which are fallen in the pit, and do cover them; then put themselves under the same raft" and there they sit in spiritual union, in song and in motion.

Diereville also gave a description of the sweat hut:

"They dig a hole as

long as themselves, & line it on both sides with stones which have been

heated at the fire until they are almost red; after that they place a layer of

Fir branches at the bottom, & lie down at full length upon them. They are

then covered with other branches, which, because of their bituminous nature,

give forth a dense vapour as they grow warm; it is not long before they are

sweating to the very bone, & for as long a time as they desire. What

surprised me most, was to know that these sudorific Ovens are always

constructed on the edge of a Lake or River, & that the Indians emerge all

dripping, only to plunge instantly into the water."39

(Diereville.)

As for tobacco: it was to be for the Micmac

always ready at hand, he was always in need of it. Tobacco was therfore an

easily traded item; it was a unversal medium of exchange. (The other easily

traded commodities were powder and shot, and, of course, liquor.)40 The natives

kept tobacco on their person at all times; they "have certain small bags

of leather hanging around about their necks or at their girdles."41 "They

smoke with excessive eagerness ... men, women, girls and boys, all find their

keenest pleasure in this way."42

And dancing:

"These ridiculous

Dancers follow one another around in a circle, clinging together & moving

forward very slowly, by leaping with joined feet, executing contortions &

making faces, each more hideous than the last. A certain vocal note like this:

Houen, houen, houen, if one can so express it, marks the cadence, & they

pause from time to time to give utterance to the terrifying yells with which

the dances always end. The instrument which provides the accompaniment is

perfectly suited to all this; it is a little stick about a foot long, which an

Indian who is not dancing, strikes against a tree, or some other object,

according to the place in which they happen to be, singing through his nose at

the same time."43

(Diereville.)

"They put some

number of beans, coloured and painted of the one side in a platter; and, having

stretched out a skin on the ground, they play thereupon, striking with the dish

upon this skin, and by that means the beans do skip in the air, and do not all

fall on that part that they be coloured; and in that consisteth the chance and

hazard - and according to their chance they have a certain number of quills

made of rushes, which they distribute to him that winneth for to keep the

reckoning."44 (Lescarbot.)

Micmac society was paternal, like that of the European society, versus, Iroquoian

social organization which was maternal.45 In Diereville's Relation, we see where an

analogy was made of the beaver to the family structure of the Micmac. The aged

beaver watches over all the rest. Once a beaver establishes his family in a

spot the family will not allow any other beavers to come into the territory and

will go to war to defend their stake and deal with "vagabond

beavers."46The men, apparently, had no care for anything but hunting and going off to war: the women, "neither being forced or tormented" did all the work.47 Women were not allowed to sit in on any of the councils or attend any of the feasts.48 Where a kill had been made on a hunt the animal would be left where it fell; the women would "go flay it and to fetch it, yea, were it three leagues off ..." The woman made all the clothes for the family, quietly chewing and sewing.49 When, in the spring, it was time to obtain a store of bark for their houses and the canoes; again, it was the women who did all the work. Whether out of fear or love, the women were not heard to complain.50