The Magna Carta is seen as one of the most influential legal documents in British history. Indeed Lord Denning (1899 -1999) a distinguished British Judge and second only to the Lord Chief Justice as Master of the Rolls, called the document “the greatest constitutional document of all time – the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot". However, its original conception was not nearly as successful.

The

Magna Carta, also know as Magna Carta Libertatum (the Great Charter of

Freedoms), was so called because the original version was drafted in

Latin. It was introduced by some of the most notable barons of the

thirteenth century in an act of rebellion against their King, King John I

(24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216).

The

Magna Carta, also know as Magna Carta Libertatum (the Great Charter of

Freedoms), was so called because the original version was drafted in

Latin. It was introduced by some of the most notable barons of the

thirteenth century in an act of rebellion against their King, King John I

(24 December 1166 – 19 October 1216).Increased taxes, the Kings’ excommunication by Pope Innocent III in 1209 and his unsuccessful and costly attempts to regain his empire in Northern France had made John hugely unpopular with his subjects. Whilst John was able to repair his relationship with the Pope in 1213, his failed attempt to defeat Phillip II of France in 1214 and his unpopular fiscal strategies led to a baron’s rebellion in 1215.

Whilst an uprising of this type was not unusual, unlike previous rebellions the barons did not have a clear successor in mind to claim the throne. Following the mysterious disappearance of Prince Arthur, Duke of Brittany, John’s nephew and son of his late brother Geoffrey (widely believed to have been murdered by John in an attempt to keep the throne), the only alternative was Prince Louis of France. However, Louis’ nationality (France and England had been warring for thirty years at this point) and his weak link to the throne as husband to John’s niece made him less than ideal.

As a result, the baron’s focused their attack on John’s oppressive rule, arguing that he was not adhering to the Charter of Liberties. This charter was a written proclamation issued by John’s ancestor Henry I when he took the throne in 1100, which sought to bind the King to certain laws regarding the treatment of church officials and nobles and was in many ways a precursor to the Magna Carta.

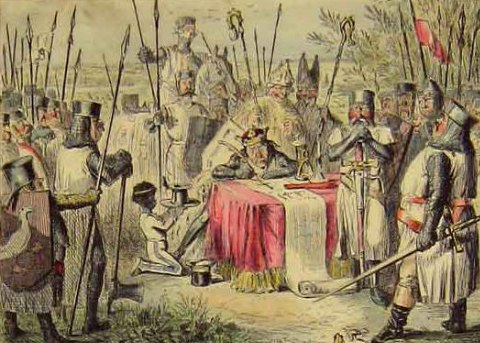

Negotiations took place throughout the first six months of 1215 but it was not until the baron’s entered the King’s London Court by force on 10 June, supported by Prince Louis and the Scottish King Alexander II, that the King was persuaded to affix his great seal to the ‘Articles of the Barons’, which outlined their grievances and stated their rights and privileges.

This significant moment, the first time a ruling King had been forcibly persuaded to renounce a great deal of his authority, took place at Runnymede, a meadow on the banks of the River Thames near Windsor on 15 June. For their part, the barons renewed their oaths of allegiance to the King on 19 June 1215. The formal document which was drafted by the Royal Chancery as a record of this agreement on 15 July was to become known retrospectively as the first version of the Magna Carta.

Whilst both the King and the baron’s had agreed to the Magna Carta as a means of reconciliation, there was still huge distrust on both sides. The baron’s had really wanted to overthrow John and see a new monarch take the throne. For his part John reneged on the most crucial section of the document, now known as Clause 61, as soon as the baron’s left London.

The clause stated that an established committee of barons had the ability to overthrow the King should he defy the charter at any time. John recognised the threat this posed and had the Pope’s full support in his rejection of the clause, because the Pope believed it called into question the authority of not only the King but the Church as well.

Sensing

the failure of the Magna Carta in curbing John’s unreasonable behaviour

the baron’s promptly changed tack and reinitiated their rebellion with a

view to replacing the monarch with Prince Louis of France, thrusting

Britain head long into the civil war known as the First Baron’s War. So

as a means of promoting peace the Magna Carta was a failure, legally

binding for only three months. It was not until John’s death from

dysentery on 19th October 1216 whilst he was mounting a siege on the

East of England that the Magna Carta finally made its mark.

Sensing

the failure of the Magna Carta in curbing John’s unreasonable behaviour

the baron’s promptly changed tack and reinitiated their rebellion with a

view to replacing the monarch with Prince Louis of France, thrusting

Britain head long into the civil war known as the First Baron’s War. So

as a means of promoting peace the Magna Carta was a failure, legally

binding for only three months. It was not until John’s death from

dysentery on 19th October 1216 whilst he was mounting a siege on the

East of England that the Magna Carta finally made its mark.Following fractions between Louis and the English barons, the royalist supporters of John’s son and heir, Henry III, were able to clinch a victory over the barons at the Battles of Lincoln and Dover in 1217. However, keen to avoid a repeat of the rebellion, the failed Magna Carta agreement was reinstated by William Marshal, the young Henry’s protector, as the Charter of Liberties - a concession to the barons. This version of the charter was edited to include 42 rather than 61 clauses, with clause 61 being notably absent.

On reaching adulthood in 1227, Henry III reissued a shorter version of the Magna Carta, which was the first to become part of English Law. Henry decreed that all future charters must be issued under the King’s seal and between the 13th and 15th centuries the Magna Carta is said to have been reconfirmed between 32 and 45 times, having last been confirmed by Henry VI in 1423.

It was during the Tudor period however, that the Magna Carta lost its place as a central part of English politics. This was partly because of the newly established Parliament but also because people began to recognise that the Charter as it stood arose from Henry III’s less dramatic reign and Edward I’s subsequent amendments (Edward’s 1297 version is the version of the Magna Carta recognised by English Law today) and was no more extraordinary than any other statute in its liberties and limitations.

It was not until the English Civil War that the Magna Carter shook off its less than successful origins and began to represent a symbol of liberty for those aspiring to a new life, becoming a major influence on the Constitution of the United States of America and the Bill of Rights, and much later the former British dominions of Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the former Union of South Africa and Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). However, by 1969 all but three of the clauses in the Magna Carta had been removed from the law of England and Wales.

Clauses still in force today

The clauses of the 1297 Magna Carta which are still on statute are- Clause 1, the freedom of the English Church.

Clause 9 (clause 13 in the 1215 charter), the "ancient liberties" of the City of London.

Clause 39 (clause 39 in the 1215 charter), a right to due process:

"No free man shall be arrested,

or imprisoned, or deprived of his property, or outlawed, or exiled, or

in any way destroyed, nor shall we go against him or send against him,

unless by legal judgement of his peers, or by the law of the land."

And what of the Magna Carta’s relevance today?

Although the Magna Carta is generally thought of as the document that was forced on King John in 1215, the almost immediate annulment of this version of the charter means it bears little resemblance to English Law today and the name Magna Carta actually refers to a number of amended statutes throughout the ages as opposed to any one document. Indeed the original Runnymede Charter was not actually signed by John or the baron’s (the words Data per manum nostrum which appeared on the charter proclaimed that the King was in agreement with the document and, as per common law at the time, the King’s seal was deemed sufficient authenticity) and so would not be legally binding by today’s standards.Unlike many nations throughout the world the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland has no official written constitution, because the political landscape has evolved over time and is continually amended by Parliamentary acts and decisions made by the Courts of Law. Indeed the Magna Carta’s many revisions and subsequent repeals means that in reality it is more of a symbol of freedom of the (not so) common people in the face of a tyrannical monarch, which has been emulated in Constitutions throughout the world, most famously perhaps in the United States.

In perhaps a telling sign of the opposing views of Briton’s today, in the BBC History’s 2006 Poll to find a date for ‘Britain day’ – a proposed day to celebrate British identity – 15 June (the date the King’s seal was affixed to the first version of the Magna Carta) – received the most votes of all historical dates of significance. However, in an ironic contrast a 2008 survey by YouGov, the internet-based market research firm, found that 45% of British people did not actually know what the Magna Carta was…

http://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/The-Origins-of-the-Magna-Carta/

----

MAGNA CARTA- in Canada

When:June 12, 2015 toDecember 29, 2015

http://www.magnacartacanada.ca/exhibition/

--------------

God bless our Commonwealth of Nations formerly The British

Empire (b4 that Little France)

Rise of Nation State England

- Magna Carta / First Parliament -

King Henry III, Simon de Monfort

Magna Carta

Magna Carta (Latin, meaning Great Charter). An impression of the Great Seal was

attached to it. Many copies of the Great Charter were made by royal clerks in

the summer of 1215. Magna Carta was granted to all freemen of England, but the

barons gained most from it.

Version of Magna Carta 1225, the third reissue with

amendments.

Click the document for

an enlargement.

John was not to ask for scutage

until his tenants-in-chief had agreed to it. Relief was fixed at £100. John had

considered the giving of justice to be a personal favor which he could refuse

if he wanted to. He made some unfortunate barons pay large sums of money just

to get a fair trail. John was not to sell or deny justice to anyone.

A committee of twenty-five barons

was chosen to keep a check on the King. He preferred to fight rather than allow

barons to sit in judgment on him. So in September 1215, civil war broke out

again. John hired soldiers from the Continent and put up a strong resistance.

On the night of October 18, 1216, he died suddenly at Newark in

Nottinghamshire, after heavy eating and drinking.

"At his end," wrote a

chronicler, "few mourned for him." However, John's death did not mean

Magna Carta was forgotten. It became part of the law of the land and in the

years ahead barons made sure that the kings remembered what it said.

Henry III (1216 - 1272)

John's nine-year old son was crowned King Henry III. A group of loyal barons

began to govern the country until the boy was old enough to rule.

Left: Illuminated manuscript shows Henry III

holding one of his churches.

Right: Gilt-bronze-effigy of King Henry III in Westmenster Abbey.

Henry commissioned ecclesiastical buildings, most

notably Westminster Abbey. Henry is shown directing construction at Westminster

Abbey, built to house the shrine of Edward the Confessor.

He allowed his French wife,

Eleanor, to crowd his court with her friends and relations. Foreigners were

given large estates and important lands. Henry even allowed the Pope to appoint

about 300 foreign clergymen to English churches. Henry was forced to hand over

most of his power to a council of fifteen barons led by Simon Monfort.

Simon de Monfort / First

Parliament

For a while, Monfort was practically the ruler of England. He held a Great

Council to which he invited not only the nobles who supported him but also the

representatives of ordinary freemen. Each county was asked to send two knights,

and each town that was friendly to him sent two burgesses (citizens). This sort

of assembly later came to be called a "Parliament."

The rule of Simon de Montfort

came to a sudden end in the summer of 1265. Many of his followers changed sides

,and he was defeated by Prince Edward, the King's eldest son. Edward took Simon

de Montfort's idea. From time to time, he invited knights and burgesses to

attend his Great Council of nobles. He listened to their complaints and asked

them to agree, in the name of the people to the collection of certain taxes.

These gatherings gave the king

and his subjects a chance to parley (talk). This is how we get the word

"Parliament."

King Edward I presiding over a Parliamentary

session, c.1278. Below the dais, the justices and law officers sit in the

center on woolsacks. Two clerks note the proceedings. The lords are mostly on

the kng's left, and the bishops and abbots are on his right. (No commons are

present on this occasion.)

Lords and Commons

The Barons and Bishops of the Great Council were known as the "Lords"

- The knights and burgesses, and the "Commoners." This is how the two

houses of parliament were developed: Lords and Commons.

"Le roi le veult." The king wills it - it becomes law.

Mr. Sedivy's Lecture Notes & Historical Info

The

Celts

| Gallic He-Men | Celtic Culture, Trade, Religion, Women |

| Threat of the Celts - Celtic Battles and Conquests

|

-

Rise of Nation State England -

| Roman Conquest of Britain | Christianity in Britain |

| Customs: Thanes, Churls, Thralls, Wergeld, Folk-Moot

|

| Dark Ages: Alfred the Great, Edward the Elder, Athelstan

|

| The Return of the Vikings |

| Kings of Britain: Aethelred, Cnut, Edward the Confessor

|

| Bayeaux Tapestry, William the Conqueror,

Edward the Confessor, Harold Godwinson, Harold II |

| The Crusades: Richard Lion Heart, Pope Urban |

| King John, Innocent III, Archbishop Stephen Langton

|

| Magna Carta / First Parliament |

Wales

and Scotland

| Wales: Edward I, Llewellyn, Snowdonia |

| Scotland: Alexander III, John Balliol,

William Wallace, Robert Bruce, King Edward II |

The

100 Years War

| Edward III, Longbows at Crecy, Edward IV, Black Prince

|

| Henry V, King Charles VI, Battle at Calais, Treaty of Troyes

|

More Information

| Other Kings of the Dark and Middle Ages:

William II, Henry I, Henry II |

| The British Monarchy's Peerage: Dukes, Viscounts,

Marquess, Earls, Baronets, and Barons |

Class

Activities

Roman Conquest Comparison

Battle of Agincourt

Related

Information

Mr. Sedivy's World History - The Middle Ages

The Complete Bayeux Tapestry

Roman Catholic Church in the Middle Ages / Crusades

The Hundred Years War

King Henry VIII

The Interesting Life of Elizabeth I

The Stuarts - James I, Charles I, Charles II, James II

Oliver Cromwell

- Magna Carta / First Parliament -

King Henry III, Simon de Monfort

Magna Carta (Latin, meaning Great Charter). An impression of the Great Seal was attached to it. Many copies of the Great Charter were made by royal clerks in the summer of 1215. Magna Carta was granted to all freemen of England, but the barons gained most from it.

Version of Magna Carta 1225, the third reissue with amendments.

Click the document for an enlargement.

John's nine-year old son was crowned King Henry III. A group of loyal barons began to govern the country until the boy was old enough to rule.

Left: Illuminated manuscript shows Henry III holding one of his churches.

Right: Gilt-bronze-effigy of King Henry III in Westmenster Abbey.

Henry commissioned ecclesiastical buildings, most notably Westminster Abbey. Henry is shown directing construction at Westminster Abbey, built to house the shrine of Edward the Confessor.

For a while, Monfort was practically the ruler of England. He held a Great Council to which he invited not only the nobles who supported him but also the representatives of ordinary freemen. Each county was asked to send two knights, and each town that was friendly to him sent two burgesses (citizens). This sort of assembly later came to be called a "Parliament."

King Edward I presiding over a Parliamentary session, c.1278. Below the dais, the justices and law officers sit in the center on woolsacks. Two clerks note the proceedings. The lords are mostly on the kng's left, and the bishops and abbots are on his right. (No commons are present on this occasion.)

The Barons and Bishops of the Great Council were known as the "Lords" - The knights and burgesses, and the "Commoners." This is how the two houses of parliament were developed: Lords and Commons.

| Gallic He-Men | Celtic Culture, Trade, Religion, Women |

| Threat of the Celts - Celtic Battles and Conquests |

| Roman Conquest of Britain | Christianity in Britain |

| Customs: Thanes, Churls, Thralls, Wergeld, Folk-Moot |

| Dark Ages: Alfred the Great, Edward the Elder, Athelstan |

| The Return of the Vikings |

| Kings of Britain: Aethelred, Cnut, Edward the Confessor |

| Bayeaux Tapestry, William the Conqueror,

Edward the Confessor, Harold Godwinson, Harold II |

| The Crusades: Richard Lion Heart, Pope Urban |

| King John, Innocent III, Archbishop Stephen Langton |

| Magna Carta / First Parliament |

| Wales: Edward I, Llewellyn, Snowdonia |

| Scotland: Alexander III, John Balliol,

William Wallace, Robert Bruce, King Edward II |

| Edward III, Longbows at Crecy, Edward IV, Black Prince |

| Henry V, King Charles VI, Battle at Calais, Treaty of Troyes |

| Other Kings of the Dark and Middle Ages:

William II, Henry I, Henry II |

| The British Monarchy's Peerage: Dukes, Viscounts,

Marquess, Earls, Baronets, and Barons |

Roman Conquest Comparison

Battle of Agincourt

Mr. Sedivy's World History - The Middle Ages

The Complete Bayeux Tapestry

Roman Catholic Church in the Middle Ages / Crusades

The Hundred Years War

King Henry VIII

The Interesting Life of Elizabeth I

The Stuarts - James I, Charles I, Charles II, James II

Oliver Cromwell

http://members.tripod.com/mr_sedivy/engrise13.html

---

God bless our troops, then, now ...always... thank u 4 r freedoms

Standing Strong & True (For Tomorrow) Official Music Video (HD)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuNeV0fMflw

The Law of First Nations

The Law of First Nations

The law of First Nations deals with issues such as:

- comprehensive

and specific land and property compensation claims;

- treaty claims

and interpretation;

- aboriginal

self-government;

- claims to

renewable and nonrenewable natural resources;

- hunting,

fishing and trapping rights;

- government

relations;

- economic

development;

- taxation;

and various public policy issues.

Abuse continued. In order to compel compliance the Quebec Act of 1774 extended Quebec's territory to include the land between the Appalachian height and the Mississippi River and from just south of Lake of the Woods to the Gulf of Mexico. The American Revolution of 1776 took back most of the extended Quebec lands.

Title to Indian land was taken in return for the following:

First Nations argue for an interpretation based on the "spirit and intent" of the treaties. The provinces and the federal government say the interpretation should be based on the express wording of the Treaty documents.

After the Constitution Act, 1982 was in place and in particular section 35, the Court came to the conclusion that overly strict interpretation of the treaties would lead to continued injustice. The decisions re: Nowegijick v. The Queen (1983) and re: Simon v. The Queen (1985) resulted in the court adopting the follow rule of construction:

The Constitution Act - 1982, reinforces aboriginal rights in section 35

This case dealt with section 35. (1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 which states:

The Court ruled that Sparrow had been exercising a protected aboriginal right to fish for food in traditional fishing waters of his Nation. That right had been progressively regulated over the years, but regulation alone did not extinguish the right, which continued to "exist" though subject to regulation prior to 1982. The Court ruled that regulation of a right does not extinguish it.

The Early Years

The Royal Proclamation of October 7, 1763 has been called the Magna Carta of Indian rights. In part, this Proclamation was intended to end the abuse which had marked dealings with Indians.Abuse continued. In order to compel compliance the Quebec Act of 1774 extended Quebec's territory to include the land between the Appalachian height and the Mississippi River and from just south of Lake of the Woods to the Gulf of Mexico. The American Revolution of 1776 took back most of the extended Quebec lands.

Canada - Nationhood & Expansion

Canada's formation and expansion

to the Pacific and north had a profound impact on the First Nations

people.

After the American Revolution two new provinces were created; Ontario and New Brunswick, to accommodate the United Empire Loyalists who were moving out of the United States.

In 1867 four provinces, Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia joined to form Canada. Canada's expansion was swift:

After the American Revolution two new provinces were created; Ontario and New Brunswick, to accommodate the United Empire Loyalists who were moving out of the United States.

In 1867 four provinces, Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia joined to form Canada. Canada's expansion was swift:

-

1868 - Rupert's Land was purchased and added to Canada;

- 1870 - Manitoba was carved out of a portion of Rupert's Land;

-

1871 - There was union with British Columbia on the promise to expedite the completion of the cross Canada railway;

- 1873 - Prince Edward Island joined Confederation;

- 1880 - Manitoba acquired more territory from Northwest Territories;

- 1886 - Islands and territories adjacent to Rupert's Land were added;

- 1898 - Yukon Territory formed out of Northwest Territories;

- 1905 - Alberta and Saskatchewan became provinces;

- 1912 - Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec acquired territory from Northwest Territories to form their present boundaries;

- 1949 - Newfoundland, which includes Labrador, joined Confederation;

- 1999 - Nunavut was formed out of the eastern part of Northwest Territories.

The Indian Treaties

The treaty process was implemented after 1870 to open the route west. These Treaties are known as the numbered Treaties. Treaties One through Eleven.Title to Indian land was taken in return for the following:

- Reserves of approximately one square mile per family of five;

- Continued exercise of hunting, fishing and trapping rights;

- The promise of schools on the Reservations. (To this day this is taken as a commitment by the government to provide education for the children);

- The promise of a medicine chest. (This has been construed by the Courts to be a promise of health services);

First Nations argue for an interpretation based on the "spirit and intent" of the treaties. The provinces and the federal government say the interpretation should be based on the express wording of the Treaty documents.

After the Constitution Act, 1982 was in place and in particular section 35, the Court came to the conclusion that overly strict interpretation of the treaties would lead to continued injustice. The decisions re: Nowegijick v. The Queen (1983) and re: Simon v. The Queen (1985) resulted in the court adopting the follow rule of construction:

"treaties and statutes dealing with Indians should be given a fair, large and liberal construction and doubtful expressions resolved in favour of the Indians, in the sense in which they would be naturally understood by the Indians."Subsequent decisions have eroded that rule. In re: Mitchell v. Peguis Indian Band (1990) the majority of the court observed that, in interpretation statutes, the intention of Parliament is the determining factor, not the views of Indians whose rights might be affected. Regarding Treaties the court held that the rule does not apply in circumstances where Indians are educated and urbanized re: Howard v. The Queen (1994).

The Constitution Act - 1982, reinforces aboriginal rights in section 35

PART IIRe: Sparrow v. The Queen (1990)

RIGHTS OF THE ABORIGINAL PEOPLES OF CANADA

35. (1) The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed.

(2) In this Act, "aboriginal peoples of Canada" includes the Indian, Inuit, and Metis peoples of Canada.

(3) For greater certainty, in subsection (1) "treaty rights" includes rights that now exist by way of land claims agreements or may be so acquired.

(4) Notwithstanding any other provision of this Act, the aboriginal and treaty rights referred to in subsection (1) are guaranteed equally to male and female persons.(17)

35.1 The government of Canada and the provincial governments are committed to the principal that, before any amendment is made to Class 24 of section 91 of the "Constitution Act, 1867", to section 25 of this Act or to this Part,

(a) a constitutional conference that includes in its agenda an item relating to the proposed amendment, composed of the Prime Minister of Canada and the first ministers of the provinces, will be convened by the Prime Minister of Canada; and

(b) the Prime Minister of Canada will invite representatives of the aboriginal peoples of Canada to participate in the discussions on that item.(18)

This case dealt with section 35. (1) of the Constitution Act, 1982 which states:

"The existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada are hereby recognized and affirmed."At issue was an Aboriginal right to fish salmon with a gill net for food, social and ceremonial purposes. The appellant, Mr. Sparrow, was a member of the Musqueam Band. He was charged with exceeding the net length restriction imposed on the Band's Food Fishing License pursuant to the British Columbia (General) Fishery Regulations enacted pursuant to the federal Fisheries Act.

The Court ruled that Sparrow had been exercising a protected aboriginal right to fish for food in traditional fishing waters of his Nation. That right had been progressively regulated over the years, but regulation alone did not extinguish the right, which continued to "exist" though subject to regulation prior to 1982. The Court ruled that regulation of a right does not extinguish it.

General Laws (Indian Act)

- Non Indians cannot live or otherwise use or occupy Indian reserve accept for some special exceptions.

- Reserve land are not subject to seizure under legal process.

- Employment income earned on the reserve is not subject to income taxes if the employee is an Indian.

- Personal property on reserve is exempt from provincial sales tax and GST. e.g. Cars, furniture, take out food.

Links to More Information

http://www.canadianlawsite.ca/aboriginal.htm

---

The Great Charter

Why a thirteenth-century piece of parchment endorsed by an English king who was under threat of death has meaning for Canadians today.

As it comes to Canada on its eight hundredth birthday, is Magna Carta

simply interesting as an ancient thing we Canadians can gaze upon as a

relic of history? Or is it still something to be struggled over?

Magna Charta Libertatum Angliae, the Great Charter of English Liberties, was born in strife and turmoil in 1215. With his barons’ swords not far from his throat, many of King John’s promises were very specific — and soon forgotten: “We will remove completely from their offices the kinsmen of Gerard de Athee, and in future they shall hold no offices in England.” But the document also laid down enduring principles of justice that would echo down the centuries: “To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

Today, Canadians can find in Magna Carta and its companion, the Charter of the Forest, declarations about the rule of law, guarantees of security of the person, the promise of environmental stewardship, a statement about the accountability of the Crown, and even an affirmation of women’s rights. Over the centuries, Magna Carta has matured into a venerable declaration of rights and a statement of the principles of justice, hardly posing a threat to anyone living under a government bound by law. In Canada, it seems that the liberties the medieval English fought over have long since been secured. It has become easy to celebrate Magna Carta complacently, as an ancient symbol of long-ago victories and as fodder for Monty Python routines: “We are all Britons. I am your king.” “I didn’t know we had a king. I thought we were an autonomous collective.”

Not everyone finds Magna Carta so safely mummified in history. If governments allowed Syrian-born Canadian Maher Arar to be kidnapped and tortured, where was Magna Carta’s promise of security of the person? If they secretly read our email, where is the promise of accountability? If authorities tolerate and encourage environmental degradation, where are the people’s rights to use the land? Throughout history, in fact, critics and change-makers have continued to invoke Magna Carta as a promise not yet kept. “The controversies through the ages about the meaning of Magna Carta are what keep it alive as a living document,” Peter Linebaugh, a prominent historian of Britain, said in an interview recently. This spring, as Magna Carta and the Forest Charter begin an unprecedented tour of Canada, they bring with them a remarkable heritage — and some debates that are very much alive.

Fittingly, Magna Carta, a statement of the rights of citizens, will tour Canada this year through the agency of two ordinary Canadian citizens, Len and Suzy Rodness, a lawyer and a real estate manager in Toronto. “We knew nothing,” exclaimed Suzy Rodness of the beginning of their quest to bring Magna Carta to Canada. But they knew a friend who had a relative in Durham, England, who in retirement had joined the Friends of Durham Cathedral. With a thousand-year-old cathedral to maintain, the organization was alert to fundraising opportunities, and Durham Cathedral holds three copies of Magna Carta. They were issued in 1216, 1225, and 1300. It also also holds three Charters of the Forest from 1217, 1225, and 1300.

The Rodnesses visited Durham in 2011, met the Friends of Durham Cathedral, and committed themselves to bringing the cathedral’s precious documents to Canada in 2015 for an eight-hundredth-anniversary tour. Originally, the cathedral’s 1225 Magna Carta was to be displayed but it was deemed to fragile to travel; the 1300 version will come to Canada instead.

“It takes time to organize everything, from the government approvals, to the arrangements with Durham, to the Canadian requirements,” said Suzy Rodness. To shoulder those burdens, the couple formed a non-profit organization, Magna Carta Canada, recruited a blue-ribbon board of volunteers and patrons, and set themselves to raise $2 million from sponsors and donors. With the help of Lord Cultural Resources, the Toronto-based world leader in designing museum exhibits, Magna Carta Canada began preparing a fitting presentation of the documents and building a lively multimedia show about the history and significance of Magna Carta for Canada and for human rights and democracy worldwide. Magna Carta and the Forest Charter will go on public display in four Canadian cities during 2015: at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, the Fort York Visitor Centre in Toronto, and the Alberta legislature in Edmonton.

Magna Carta has been in Canada once before. In 2010, a 1217 version from the Bodleian Library at Oxford University came to New York for the North American reunion of Oxford University alumni. At around the same time, the eruption of Iceland’s Mount Eyjafjallajökull disrupted flights to the United Kingdom, delaying its return to Britain. The Manitoba legislature seized the opportunity to negotiate a loan of Magna Carta for a three-month exhibition.

As it happened, the Queen was in Winnipeg at this time to unveil a stone from Runnymede, where Magna Carta had been endorsed. Appropriately enough, that stone became the cornerstone of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Why should Canadians see Magna Carta? To see the thing itself, for one thing: Four thousand words of medieval Latin, written on a single crammed sheet of animal-skin parchment with an ink made of dust, water, and powdered oak-apple (tannic acid extracted from galls that grow on oak trees). For another, because Magna Carta is, in the words of British historian Linda Colley, “one of the most iconic texts not just in British history but in global history.” For Suzy Rodness, the appeal is simple and powerful: “Doing this, we are learning about our country, learning what made Canada Canada — human rights, parliament, the rule of law. Our sons, now in their twenties, perhaps they never knew how fortunate they are to live in this country in this time. Now they get it, I think. Magna Carta influences all the things we take for granted.”

John soon reneged on his charter commitments, but in just over a year he was dead. His young son, Henry III, would go on to a remarkable fifty-six years on the throne and (for a king) a placid family life — “so of course he is forgotten!” laughs Harris. But Magna Carta was reissued with Henry III’s seal, and Henry later agreed to annual sittings of parliament, with more than just the barons represented. The Magna Carta concept — that an English monarch was bound by a contract with his people — endured.

The fame and reputation of Magna Carta itself waxed and waned, Harris says. “It has been reborn and reinterpreted so many times!” After the Wars of the Roses, England looked to strong kings, and monarchs like the Tudors Henry VIII and Elizabeth I were happy to let the old charter of liberty become forgotten.

When Shakespeare wrote his play King John in the 1590s, Magna Carta did not rate a mention. When English parliaments of the 1600s began to battle the Stuart monarchs and their exalted notion of the rights of kings, however, the great jurist Edward Coke excavated Magna Carta from the obscurity of ancient legal tomes. It became again a symbol of liberty. Coke helped to draft charters for the first American colonies of England, too, and Magna Carta became part of the constitutional underpinning of British colonies and settlements.

Representative government and the rule of law became entrenched in the Anglo-American world after England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the American Revolution a century later. Magna Carta began to seem safe, and tamed. Any orator could roll out praise of Magna Carta as the first statement of liberty. Muralists painted Runnymede scenes in courthouses and civic halls from London to Cleveland, and in Canada, too. Just what it stood for seemed less important, when it seemed mostly to affirm the status quo. For Britons and Canadians, Magna Carta meant constitutional monarchy, though for Americans it meant no monarchy at all. American courts repeatedly affirmed that property rights were the key point of Magna Carta, and before the Civil War property included slaves, who had no liberties and no due process. In an era of national and racial stereotypes, Magna Carta was often claimed as the unique heritage of English-speaking peoples, something peoples of other colours and continents could not achieve.

In his book The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All, Linebaugh aligns the Forest Charter with a deeper radicalism: that of indigenous peoples all over the world, striving to protect their livelihoods and their lifeways when the very lands on which they depend become state property and then private property from which they are fenced off. Magna Carta has indeed become iconic around the world — surprisingly often in ways that can still make crowned heads uneasy. For, as Linebaugh notes, the barons wrote a right of resistance into Magna Carta.

John Borrows is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria law school. He is one of the scholars advising Magna Carta Canada about the meaning of the great charter for Canadians. And he is a member of the Ojibwa nation. He talked recently about the 1973 Supreme Court of Canada case called Calder, a key precedent in Canadian treaty law, in which a judge described the Royal Proclamation of 1763 as “the Indian Magna Carta.”

The Royal Proclamation required the Crown in Canada to negotiate treaties with Aboriginal nations, a duty that cannot arbitrarily be shirked. The history of treaties suggests that the First Nations understood those treaties as sharing agreements, a plan to hold the land in common for the benefit of all, somewhat as the Forest Charter provided for England.

“Magna Carta is imperfect and it is early,” said Borrows, “but it does restrict the Crown vis-a-vis the citizens. Now we have Article 35 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which affirms Aboriginal rights.

“Again, the state cannot just do what it wants. Magna Carta carries the understanding that concentration of power can be corrupting,” Borrows continued. “We are imperfect humans, and we are never going to get there, but Magna Carta can be seen as a statement of goals — because goals are never realized. They point us toward our better selves. And they suggest why we need law — to set our better natures against our worst.”

Go see Magna Carta, just to gaze on something so ancient and so enduring. You may find yourself also engaging with ideas that still drive people engaged in fundamental struggles for justice and for rights around the world — and also here in Canada.

— by Carolyn Harris

Years of King John's reign when he affixed his seal to Magna Carta.

Number of barons who stood surety for the enforcement of Magna Carta.

Number of clauses scholars find in the 1215 version.

Number of the clause that sets a precedent for trial by jury, stating,

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned ... except by the lawful

judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Number of the clause that sets a precedent for trial by jury, stating,

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned ... except by the lawful

judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Months that passed between John accepting and then repudiating Magna Carta.

Number of surviving copies of Magna Carta that date between 1215 and 1300.

Magna Charta Libertatum Angliae, the Great Charter of English Liberties, was born in strife and turmoil in 1215. With his barons’ swords not far from his throat, many of King John’s promises were very specific — and soon forgotten: “We will remove completely from their offices the kinsmen of Gerard de Athee, and in future they shall hold no offices in England.” But the document also laid down enduring principles of justice that would echo down the centuries: “To no one will we sell, to no one deny or delay right or justice.”

Today, Canadians can find in Magna Carta and its companion, the Charter of the Forest, declarations about the rule of law, guarantees of security of the person, the promise of environmental stewardship, a statement about the accountability of the Crown, and even an affirmation of women’s rights. Over the centuries, Magna Carta has matured into a venerable declaration of rights and a statement of the principles of justice, hardly posing a threat to anyone living under a government bound by law. In Canada, it seems that the liberties the medieval English fought over have long since been secured. It has become easy to celebrate Magna Carta complacently, as an ancient symbol of long-ago victories and as fodder for Monty Python routines: “We are all Britons. I am your king.” “I didn’t know we had a king. I thought we were an autonomous collective.”

Not everyone finds Magna Carta so safely mummified in history. If governments allowed Syrian-born Canadian Maher Arar to be kidnapped and tortured, where was Magna Carta’s promise of security of the person? If they secretly read our email, where is the promise of accountability? If authorities tolerate and encourage environmental degradation, where are the people’s rights to use the land? Throughout history, in fact, critics and change-makers have continued to invoke Magna Carta as a promise not yet kept. “The controversies through the ages about the meaning of Magna Carta are what keep it alive as a living document,” Peter Linebaugh, a prominent historian of Britain, said in an interview recently. This spring, as Magna Carta and the Forest Charter begin an unprecedented tour of Canada, they bring with them a remarkable heritage — and some debates that are very much alive.

Magna Carta on tour

In the early 1200s, Magna Carta went viral in the best way medieval England could provide. In 1215 — and when it was reissued in 1216, 1217, and 1225 — multiple copies of the precious text were made and sealed with the royal seal. And, since the seal made each one a legal declaration, they were technically not “copies” but each equally valid. These were dispersed across Britain, to the castles of barons, to county seats, to the great cathedrals. Over the centuries, most would gradually succumb to war and flood and vermin. Ireland’s copy, the Magna Carta Hibernae, was destroyed as recently as 1922, in the Irish Civil War. But a few of the originals survive: Just four of the 1215 documents are known to exist, plus another nine from the following decade.Fittingly, Magna Carta, a statement of the rights of citizens, will tour Canada this year through the agency of two ordinary Canadian citizens, Len and Suzy Rodness, a lawyer and a real estate manager in Toronto. “We knew nothing,” exclaimed Suzy Rodness of the beginning of their quest to bring Magna Carta to Canada. But they knew a friend who had a relative in Durham, England, who in retirement had joined the Friends of Durham Cathedral. With a thousand-year-old cathedral to maintain, the organization was alert to fundraising opportunities, and Durham Cathedral holds three copies of Magna Carta. They were issued in 1216, 1225, and 1300. It also also holds three Charters of the Forest from 1217, 1225, and 1300.

The Rodnesses visited Durham in 2011, met the Friends of Durham Cathedral, and committed themselves to bringing the cathedral’s precious documents to Canada in 2015 for an eight-hundredth-anniversary tour. Originally, the cathedral’s 1225 Magna Carta was to be displayed but it was deemed to fragile to travel; the 1300 version will come to Canada instead.

“It takes time to organize everything, from the government approvals, to the arrangements with Durham, to the Canadian requirements,” said Suzy Rodness. To shoulder those burdens, the couple formed a non-profit organization, Magna Carta Canada, recruited a blue-ribbon board of volunteers and patrons, and set themselves to raise $2 million from sponsors and donors. With the help of Lord Cultural Resources, the Toronto-based world leader in designing museum exhibits, Magna Carta Canada began preparing a fitting presentation of the documents and building a lively multimedia show about the history and significance of Magna Carta for Canada and for human rights and democracy worldwide. Magna Carta and the Forest Charter will go on public display in four Canadian cities during 2015: at the Canadian Museum of History in Gatineau, Quebec, the Canadian Museum for Human Rights in Winnipeg, the Fort York Visitor Centre in Toronto, and the Alberta legislature in Edmonton.

Magna Carta has been in Canada once before. In 2010, a 1217 version from the Bodleian Library at Oxford University came to New York for the North American reunion of Oxford University alumni. At around the same time, the eruption of Iceland’s Mount Eyjafjallajökull disrupted flights to the United Kingdom, delaying its return to Britain. The Manitoba legislature seized the opportunity to negotiate a loan of Magna Carta for a three-month exhibition.

As it happened, the Queen was in Winnipeg at this time to unveil a stone from Runnymede, where Magna Carta had been endorsed. Appropriately enough, that stone became the cornerstone of the Canadian Museum for Human Rights.

Why should Canadians see Magna Carta? To see the thing itself, for one thing: Four thousand words of medieval Latin, written on a single crammed sheet of animal-skin parchment with an ink made of dust, water, and powdered oak-apple (tannic acid extracted from galls that grow on oak trees). For another, because Magna Carta is, in the words of British historian Linda Colley, “one of the most iconic texts not just in British history but in global history.” For Suzy Rodness, the appeal is simple and powerful: “Doing this, we are learning about our country, learning what made Canada Canada — human rights, parliament, the rule of law. Our sons, now in their twenties, perhaps they never knew how fortunate they are to live in this country in this time. Now they get it, I think. Magna Carta influences all the things we take for granted.”

John soon reneged on his charter commitments, but in just over a year he was dead.

Magna Carta becomes iconic

“King John had a knack for bringing people together in animosity to him,” said Carolyn Harris of Toronto, a recent graduate in British royal history and the author of Magna Carta and its Gifts to Canada, a companion volume for the charter’s Canadian tour. King John, desperate for funds, had been plundering England, lunging after any source of money that might prop up his lands and his throne. The barons who were among his targets — their wives and children held hostage, their castles seized, their wealth extorted — considered killing John and putting a more pliable relative on the throne. Instead, they put forth a set of rules to bind the king. At Runnymede in the Thames Valley, not far from Windsor Castle (and today’s Heathrow Airport), King John acceded to the barons’ demands. On June 15, 1215, they agreed on a guarantee of due process of law, limits on royal exactions, the people’s right to use the common lands, and a council of the barons to ensure that the king fulfilled his promises.John soon reneged on his charter commitments, but in just over a year he was dead. His young son, Henry III, would go on to a remarkable fifty-six years on the throne and (for a king) a placid family life — “so of course he is forgotten!” laughs Harris. But Magna Carta was reissued with Henry III’s seal, and Henry later agreed to annual sittings of parliament, with more than just the barons represented. The Magna Carta concept — that an English monarch was bound by a contract with his people — endured.

The fame and reputation of Magna Carta itself waxed and waned, Harris says. “It has been reborn and reinterpreted so many times!” After the Wars of the Roses, England looked to strong kings, and monarchs like the Tudors Henry VIII and Elizabeth I were happy to let the old charter of liberty become forgotten.

When Shakespeare wrote his play King John in the 1590s, Magna Carta did not rate a mention. When English parliaments of the 1600s began to battle the Stuart monarchs and their exalted notion of the rights of kings, however, the great jurist Edward Coke excavated Magna Carta from the obscurity of ancient legal tomes. It became again a symbol of liberty. Coke helped to draft charters for the first American colonies of England, too, and Magna Carta became part of the constitutional underpinning of British colonies and settlements.

Representative government and the rule of law became entrenched in the Anglo-American world after England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the American Revolution a century later. Magna Carta began to seem safe, and tamed. Any orator could roll out praise of Magna Carta as the first statement of liberty. Muralists painted Runnymede scenes in courthouses and civic halls from London to Cleveland, and in Canada, too. Just what it stood for seemed less important, when it seemed mostly to affirm the status quo. For Britons and Canadians, Magna Carta meant constitutional monarchy, though for Americans it meant no monarchy at all. American courts repeatedly affirmed that property rights were the key point of Magna Carta, and before the Civil War property included slaves, who had no liberties and no due process. In an era of national and racial stereotypes, Magna Carta was often claimed as the unique heritage of English-speaking peoples, something peoples of other colours and continents could not achieve.

Still dangerous? Magna Carta's protest heritage

Peter Linebaugh, the veteran historian of eighteenth-century Britain, found himself reading the Charter of the Forest, the 1217 document that expands on the land-use guarantees of Magna Carta. King John’s Norman forebears had asserted that they owned the forests and unoccupied lands of England. John sought to deny his subjects access to them or, better still, to charge them fees. For the barons and the commoners alike, however, the forests were precious: hunting grounds for the barons, and for ordinary people a vital source of firewood, plants, honey, pasturage, and game for the food pot. When he agreed to Magna Carta, John agreed that the vast royal forests would be “disafforested” — they would become common ground again, once more open for the use of all who needed them. After reading the Forest Charter, Linebaugh began to reconsider “his” eighteenth-century Britain, when respect for the commons was repudiated by the Enclosure Acts that transferred lands from common use to private ownership. He considered the great famines of nineteenth-century India, after common land was converted to commercial cotton plantations; the manifesto of the Chiapas rebels of southern Mexico of the 1990s, which defended the village commons against industrial agriculture; and even the protests of Nigerian women in recent decades who have seen the oil industry destroy their only sources of firewood and clean water. The protection of Magna Carta can be invoked in protest wherever justice is subverted, government becomes tyrannical, and liberties are trampled. “It became a pillar of Anglo-Saxon racism in the nineteenth century, yet it was also cited by national liberation movements — by Nelson Mandela at his trial,” said Linebaugh.In his book The Magna Carta Manifesto: Liberties and Commons for All, Linebaugh aligns the Forest Charter with a deeper radicalism: that of indigenous peoples all over the world, striving to protect their livelihoods and their lifeways when the very lands on which they depend become state property and then private property from which they are fenced off. Magna Carta has indeed become iconic around the world — surprisingly often in ways that can still make crowned heads uneasy. For, as Linebaugh notes, the barons wrote a right of resistance into Magna Carta.

Magna Carta in Canada

Canada inherited from Britain the Magna Carta principles along with constitutional monarchy, the rule of law, and other foundations of government. Are there other Canadian aspects to these documents that were drafted centuries before Europeans colonized the Americas?John Borrows is Canada Research Chair in Indigenous Law at the University of Victoria law school. He is one of the scholars advising Magna Carta Canada about the meaning of the great charter for Canadians. And he is a member of the Ojibwa nation. He talked recently about the 1973 Supreme Court of Canada case called Calder, a key precedent in Canadian treaty law, in which a judge described the Royal Proclamation of 1763 as “the Indian Magna Carta.”

The Royal Proclamation required the Crown in Canada to negotiate treaties with Aboriginal nations, a duty that cannot arbitrarily be shirked. The history of treaties suggests that the First Nations understood those treaties as sharing agreements, a plan to hold the land in common for the benefit of all, somewhat as the Forest Charter provided for England.

“Magna Carta is imperfect and it is early,” said Borrows, “but it does restrict the Crown vis-a-vis the citizens. Now we have Article 35 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which affirms Aboriginal rights.

“Again, the state cannot just do what it wants. Magna Carta carries the understanding that concentration of power can be corrupting,” Borrows continued. “We are imperfect humans, and we are never going to get there, but Magna Carta can be seen as a statement of goals — because goals are never realized. They point us toward our better selves. And they suggest why we need law — to set our better natures against our worst.”

Go see Magna Carta, just to gaze on something so ancient and so enduring. You may find yourself also engaging with ideas that still drive people engaged in fundamental struggles for justice and for rights around the world — and also here in Canada.

MAGNA CARTA BY THE NUMBERS

On June 15, 1215, King John became the first English monarch to accept a charter of limits on his power as imposed by his subjects. Neither the king nor his rebel barons expected the agreement to last for very long, but Magna Carta inspired future generations and provided the foundation for English common law, which spread throughout the Englishspeaking world, including Canada. In 2015, a surviving copy of Magna Carta and a companion document, the Charter of the Forest, will tour Canada.— by Carolyn Harris

Years of King John's reign when he affixed his seal to Magna Carta.

Number of barons who stood surety for the enforcement of Magna Carta.

Number of clauses scholars find in the 1215 version.

Number of the clause that sets a precedent for trial by jury, stating,

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned ... except by the lawful

judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Number of the clause that sets a precedent for trial by jury, stating,

“No free man shall be seized or imprisoned ... except by the lawful

judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.”

Months that passed between John accepting and then repudiating Magna Carta.

Number of surviving copies of Magna Carta that date between 1215 and 1300.

Rate This Article

1 = poor, 5 = excellent| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

------------

The incomparable Magna Carta - one of

the worlds great documents. See the 800 year old document at the Canadian

Museum of History, in Gatineau.

The clauses of Magna Carta and American Legacy

- Article by: Nicholas Vincent

- Theme: Clauses and content

Magna Carta and Its American Legacy

Before

penning the Declaration of Independence--the first of the American Charters

of Freedom--in 1776, the Founding Fathers searched for a historical precedent

for asserting their rightful liberties from King George III and the English

Parliament. They found it in a gathering that took place 561 years earlier on

the plains of Runnymede, not far from where Windsor Castle stands today. There,

on June 15, 1215, an assembly of barons confronted a despotic and cash-strapped

King John and demanded that traditional rights be recognized, written down,

confirmed with the royal seal, and sent to each of the counties to be read to

all freemen. The result was Magna Carta--a momentous achievement for the English

barons and, nearly six centuries later, an inspiration for angry American colonists.

Before

penning the Declaration of Independence--the first of the American Charters

of Freedom--in 1776, the Founding Fathers searched for a historical precedent

for asserting their rightful liberties from King George III and the English

Parliament. They found it in a gathering that took place 561 years earlier on

the plains of Runnymede, not far from where Windsor Castle stands today. There,

on June 15, 1215, an assembly of barons confronted a despotic and cash-strapped

King John and demanded that traditional rights be recognized, written down,

confirmed with the royal seal, and sent to each of the counties to be read to

all freemen. The result was Magna Carta--a momentous achievement for the English

barons and, nearly six centuries later, an inspiration for angry American colonists.

The document conceded by John and set with his seal in 1215, however, was not what we know today as Magna Carta but rather a set of baronial stipulations, now lost, known as the "Articles of the barons." After John and his barons agreed on the final provisions and additional wording changes, they issued a formal version on June 19, and it is this document that came to be known as Magna Carta. Of great significance to future generations was a minor wording change, the replacement of the term "any baron" with "any freeman" in stipulating to whom the provisions applied. Over time, it would help justify the application of the Charter's provisions to a greater part of the population. While freemen were a minority in 13th-century England, the term would eventually include all English, just as "We the People" would come to apply to all Americans in this century.

While Magna Carta would one day become a basic document of the British Constitution, democracy and universal protection of ancient liberties were not among the barons' goals. The Charter was a feudal document and meant to protect the rights and property of the few powerful families that topped the rigidly structured feudal system. In fact, the majority of the population, the thousands of unfree laborers, are only mentioned once, in a clause concerning the use of court-set fines to punish minor offenses. Magna Carta's primary purpose was restorative: to force King John to recognize the supremacy of ancient liberties, to limit his ability to raise funds, and to reassert the principle of "due process." Only a final clause, which created an enforcement council of tenants-in-chief and clergymen, would have severely limited the king's power and introduced something new to English law: the principle of "majority rule." But majority rule was an idea whose time had not yet come; in September, at John's urging, Pope Innocent II annulled the "shameful and demeaning agreement, forced upon the king by violence and fear." The civil war that followed ended only with John's death in October 1216.

A

1297 version of Magna Carta, presented courtesy of David M. Rubenstein,

is on display in the new David M. Rubenstein Gallery at the National

Archives.

A

1297 version of Magna Carta, presented courtesy of David M. Rubenstein,

is on display in the new David M. Rubenstein Gallery at the National

Archives.To gain support for the new monarch--John's 9-year-old son, Henry III--the young king's regents reissued the charter in 1217. Neither this version nor that issued by Henry when he assumed personal control of the throne in 1225 were exact duplicates of John's charter; both lacked some provisions, including that providing for the enforcement council, found in the original. With the 1225 issuance, however, the evolution of the document ended. While English monarchs, including Henry, confirmed Magna Carta several times after this, each subsequent issue followed the form of this "final" version. With each confirmation, copies of the document were made and sent to the counties so that everyone would know their rights and obligations. Of these original issues of Magna Carta, 17 survive: 4 from the reign of John; 8 from that of Henry III; and 5 from Edward I, including the version now on display at the National Archives.

Although tradition and interpretation would one day make Magna Carta a document of great importance to both England and the American colonies, it originally granted concessions to few but the powerful baronial families. It did include concessions to the Church, merchants, townsmen, and the lower aristocracy for their aid in the rebellion, but the majority of the English population would remain without an active voice in government for another 700 years.

Despite its historical significance, however, Magna Carta may have remained legally inconsequential had it not been resurrected and reinterpreted by Sir Edward Coke in the early 17th century. Coke, Attorney General for Elizabeth, Chief Justice during the reign of James, and a leader in Parliament in opposition to Charles I, used Magna Carta as a weapon against the oppressive tactics of the Stuart kings. Coke argued that even kings must comply to common law. As he proclaimed to Parliament in 1628, "Magna Carta . . . will have no sovereign."

Lord

Coke's view of the law was particularly relevant to the American experience

for it was during this period that the charters for the colonies were written.

Each included the guarantee that those sailing for the New World and their heirs

would have "all the rights and immunities of free and natural subjects."

As our forefathers developed legal codes for the colonies, many incorporated

liberties guaranteed by Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights directly

into their own statutes. Although few colonists could afford legal training

in England, they remained remarkably familiar with English common law. During

one parliamentary debate in the late 18th century, Edmund Burke observed, "In

no country, perhaps in the world, is law so general a study." Through Coke,

whose four-volume Institutes of the Laws of England was widely read by American

law students, young colonists such as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James

Madison learned of the spirit of the charter and the common law--or at least

Coke's interpretation of them. Later, Jefferson would write to Madison of Coke:

"a sounder whig never wrote, nor of profounder learning in the orthodox

doctrines of the British constitution, or in what were called English liberties."

It is no wonder then that as the colonists prepared for war they would look

to Coke and Magna Carta for justification.

Lord

Coke's view of the law was particularly relevant to the American experience

for it was during this period that the charters for the colonies were written.

Each included the guarantee that those sailing for the New World and their heirs

would have "all the rights and immunities of free and natural subjects."

As our forefathers developed legal codes for the colonies, many incorporated

liberties guaranteed by Magna Carta and the 1689 English Bill of Rights directly

into their own statutes. Although few colonists could afford legal training

in England, they remained remarkably familiar with English common law. During

one parliamentary debate in the late 18th century, Edmund Burke observed, "In

no country, perhaps in the world, is law so general a study." Through Coke,

whose four-volume Institutes of the Laws of England was widely read by American

law students, young colonists such as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James

Madison learned of the spirit of the charter and the common law--or at least

Coke's interpretation of them. Later, Jefferson would write to Madison of Coke:

"a sounder whig never wrote, nor of profounder learning in the orthodox

doctrines of the British constitution, or in what were called English liberties."

It is no wonder then that as the colonists prepared for war they would look

to Coke and Magna Carta for justification.By the 1760s the colonists had come to believe that in America they were creating a place that adopted the best of the English system but adapted it to new circumstances; a place where a person could rise by merit, not birth; a place where men could voice their opinions and actively share in self-government. But these beliefs were soon tested. Following the costly Seven Years' War, Great Britain was burdened with substantial debts and the continuing expense of keeping troops on American soil. Parliament thought the colonies should finance much of their own defense and levied the first direct tax, the Stamp Act, in 1765. As a result, virtually every document--newspapers, licenses, insurance policies, legal writs, even playing cards--would have to carry a stamp showing that required taxes had been paid. The colonists rebelled against such control over their daily affairs. Their own elected legislative bodies had not been asked to consent to the Stamp Act. The colonists argued that without either this local consent or direct representation in Parliament, the act was "taxation without representation." They also objected to the law's provision that those who disobeyed could be tried in admiralty courts without a jury of their peers. Coke's influence on Americans showed clearly when the Massachusetts Assembly reacted by declaring the Stamp Act "against the Magna Carta and the natural rights of Englishmen, and therefore, according to Lord Coke, null and void."

But

regardless of whether the charter forbade taxation without representation or

if this was merely implied by the "spirit," the colonists used this

"misinterpretation" to condemn the Stamp Act. To defend their objections,

they turned to a 1609 or 1610 defense argument used by Coke: superiority of

the common law over acts of Parliament. Coke claimed "When an act of parliament

is against common right or reason, or repugnant, or impossible to be performed,

the common law will control it and adjudge such an act void. Because the Stamp

Act seemed to tread on the concept of consensual taxation, the colonists believed

it, "according to Lord Coke," invalid.

But

regardless of whether the charter forbade taxation without representation or

if this was merely implied by the "spirit," the colonists used this

"misinterpretation" to condemn the Stamp Act. To defend their objections,

they turned to a 1609 or 1610 defense argument used by Coke: superiority of

the common law over acts of Parliament. Coke claimed "When an act of parliament

is against common right or reason, or repugnant, or impossible to be performed,

the common law will control it and adjudge such an act void. Because the Stamp

Act seemed to tread on the concept of consensual taxation, the colonists believed

it, "according to Lord Coke," invalid.The colonists were enraged. Benjamin Franklin and others in England eloquently argued the American case, and Parliament quickly rescinded the bill. But the damage was done; the political climate was changing. As John Adams later wrote to Thomas Jefferson, "The Revolution was in the minds of the people, and this was effected, from 1760 to 1775, in the course of 15 years before a drop of blood was shed at Lexington."

Relations between Great Britain and the colonies continued to deteriorate. The more Parliament tried to raise revenue and suppress the growing unrest, the more the colonists demanded the charter rights they had brought with them a century and a half earlier. At the height of the Stamp Act crisis, William Pitt proclaimed in Parliament, "The Americans are the sons not the bastards of England." Parliament and the Crown, however, appeared to believe otherwise. But the Americans would have their rights, and they would fight for them. The seal adopted by Massachusetts on the eve of the Revolution summed up the mood--a militiaman with sword in one hand and Magna Carta in the other.

Armed resistance broke out in April 1775. Fifteen months later, the final break was made with the immortal words of the Declaration of Independence: "We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all Men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness." Although the colonies had finally and irrevocably articulated their goal, Independence did not come swiftly. Not until the surrender of British forces at Yorktown in 1781 was the military struggle won. The constitutional battle, however, was just beginning.

In the war's aftermath, many Americans recognized that the rather loose confederation of states would have to be strengthened if the new nation were to survive. James Madison expressed these concerns in a call for a convention at Philadelphia in 1787 to revise the Articles of Confederation: "The good people of America are to decide the solemn question, whether they will by wise and magnanimous efforts reap the just fruits of that Independence which they so gloriously acquired . . . or whether by giving way to unmanly jealousies and prejudices, or to partial and transitory interests, they will renounce the auspicious blessings prepared for them by the Revolution." The representatives of the states listened to Madison and drew heavily from his ideas. Instead of revising the Articles, they created a new form of government, embodied in the Constitution of the United States. Authority emanated directly from the people, not from any governmental body. And the Constitution would be "the supreme Law of the Land"--just as Magna Carta had been deemed superior to other statutes.

In 1215, when King John confirmed Magna Carta with his seal, he was acknowledging the now firmly embedded concept that no man--not even the king--is above the law. That was a milestone in constitutional thought for the 13th century and for centuries to come. In 1779 John Adams expressed it this way: "A government of laws, and not of men." Further, the charter established important individual rights that have a direct legacy in the American Bill of Rights. And during the United States' history, these rights have been expanded. The U.S. Constitution is not a static document. Like Magna Carta, it has been interpreted and reinterpreted throughout the years. This has allowed the Constitution to become the longest-lasting constitution in the world and a model for those penned by other nations. Through judicial review and amendment, it has evolved so that today Americans--regardless of gender, race, or creed--can enjoy the liberties and protection it guarantees. Just as Magna Carta stood as a bulwark against tyranny in England, the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights today serve similar roles, protecting the individual freedoms of all Americans against arbitrary and capricious rule.

Image Top Right:

A 1297 version of Magna Carta, presented courtesy of David M. Rubenstein, is on display in the West Rotunda Gallery at the National Archives.

Image Middle Left:

Sir Edward Coke's reinterpretation of Magna Carta provided an argument for universal liberty in England and gave American colonists a basis for their condemnation of British colonial policies. (Library of Congress)

Image Bottom Right:

Members of the British government and church mourn the demise of the Stamp Act. (Library of Congress)

----

THE LAW

Magna Carta

Contents

·

Abstract

·

Form

Magna Carta

Abstract

The Magna Carta (literally, the “Great

Paper” or “Great Charter”) was acceded to by the King of England John in 1215

at Runnymede (in the county of Surrey, England), following an armed rebellion

by his barons. This Charter arguably laid a number of the foundations for

modern constitutional government.

It guaranteed the freedom of the Church,

restricted the Crown of England´s powers to raise taxes, and guaranteed certain

minimum rights of due process. The Magna Carta was frequently confirmed and

renewed by successive English monarchs during the Middle Ages, but tended to be

regarded no differently from an ordinary Statute of the time. It was in fact of

little real effect in constraining the powers of the Kings of England.

By the 16th century, for various

political reasons, the Charter came to be represented as a more significant

source of constitutional legitimacy for both Crown and citizens. The Magna

Carta later, then, played a role in the political and legal power plays that

marked the run-up to the English Civil War.

Parts of the Magna Carta continued to be

renewed into the 18th century; however, with the rise of modern parliamentary

democracy, the Great Charter became less relevant, and by the late 19th century

most clauses had been repealed, so that the document today is primarily of

cultural and historical relevance.

It was in force for only a few months,

when it was violated by the king. Just over a year later, with no resolution to

the war, the king died, being succeeded by his 9-year old son, Henry III. The

Charter (Carta) was reissued again, with some revisions, in 1216, 1217 and

1225.

Introduction

Emerging as a thirteenth-century

agreement between crown and aristocracy, the charter came to be seen as

representing wider legal and political principles, especially those of lawful

and limited government.

Background

The charter was drafted against a

backdrop of complex political and military disputes. At the center of each was

King John (c. 1167–1216), the Plantagenet ruler of England, Wales, Ireland, and

much of northern France. A descendant of the Normans who had conquered England

a century earlier, John would become the first to reside permanently in

England. He was crowned king in 1199 and immediately faced competing claims on

his French territories, not least those of King Philip II (1165–1223) of

France. In a series of wars with Philip and his allies, John lost much of his

continental holdings by 1204. The following years saw him invade successfully

Scotland, Ireland, and Wales. To exacerbate these military demands, John fell

foul of Pope Innocent II (d. 1143). In 1207 the king contested the pope’s

nominee for archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton (c. 1150–1228). As a

result, the pope placed England under an interdict on religious worship,

excommunicated the king, and sided with Philip.

In attempting to pay for his military

activities, John imposed increasing financial demands on the Anglo-Norman

aristocracy. Combined with complaints about royal interference with the

administration of justice, the result was a rebellion against the king. In 1212

John acquiesced to the pope, agreeing to surrender his kingdoms to the papacy

as feudal overlord and repurchasing them from him. An invasion of England was

narrowly avoided the following year when the French fleet was destroyed. John

then invaded France in 1214 in the hope of reclaiming his territories there. He

suffered a major defeat at Bouvines, resulting in the loss of most of his

remaining continental possessions.

John soon faced additional problems

within England. Encouraged by Archbishop Langton, the Anglo-Norman barons there

remonstrated against the king’s financial demands and judicial interference. In

May 1215 they took London by military force. A truce was sought and

representatives met at Runnymede (Surrey), a meadow west of London on the river

Thames, in June 1215. After much discussion, they agreed to a document of

compromises called the Articles of the Barons. This was superseded by the

charter subsequently known as Magna Carta.

Form

Formally, Magna Carta was a royal letter

written in Latin dealing with a wide variety of issues: the freedom of the

church, feudal customs, taxation, trade, and the law. This was not the first

attempt to limit political power by a written charter. In England, for example,

the Charter of Liberties issued by Henry I (c. 1068–1135) predated Magna Carta

by over a century. Magna Carta was also similar to contemporaneous continental

charters and legislation. Many of its rules came from a common pool of European

political and legal thought, not least the canon law of the church. In the short

term, the most potentially radical element of Magna Carta was probably the

provision for a commission of barons to ensure royal compliance. But this came

to nothing. Contrary to subsequent interpretation, it had little to do with the

lesser landholders or the vast peasantry of England.

John renounced Magna Carta almost

immediately. The pope, too, issued a papal bull against the agreement because

it had been imposed by force. Civil war returned. Numerous barons now aligned

themselves with Louis (1187–1226), Philip’s son and later Louis VIII of France,

who invaded England in May 1216 with a significant army. Louis subsequently

occupied London, where he was received enthusiastically by the barons and was

proclaimed king of England. John made some military gains, but died of

dysentery in October 1216. With his death, the barons’ complaints were less

pressing. John’s nine-year-old son, Henry III (1207–1272), was seen as more

politically malleable and was crowned English king. His regent, William

Marshall (c. 1146–1219), one of the signatories of Magna Carta, revised and

reissued the document in November 1216. Marshall was also able to convince most