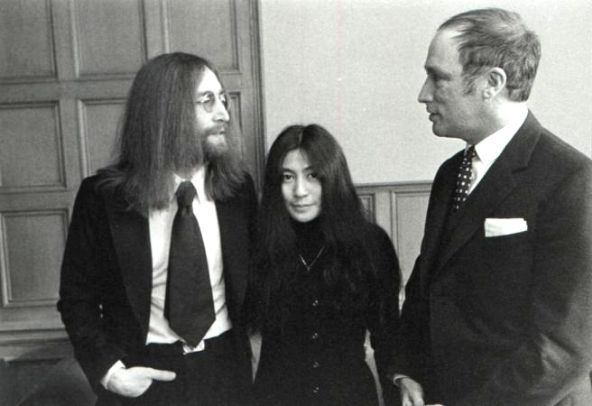

John Lennon and Yoko Ono meet PM Pierre Elliott Trudeau

Year One A.P.

(After Peace)

Year One A.P.

(After Peace)

Researched by

John Whelan, Chief Researcher for the Ottawa Beatles Site

Special thanks to the National

Archives of Canada for allowing

the Ottawa Beatle Site permission to e-publish the Duncan Cameron photos below. All photographs listed on this web page are on file at the National Archives of Canada. Please read the copyright notice at the bottom of page regarding the photos.

the Ottawa Beatle Site permission to e-publish the Duncan Cameron photos below. All photographs listed on this web page are on file at the National Archives of Canada. Please read the copyright notice at the bottom of page regarding the photos.

John

Lennon and Yoko Ono meet with

Canada's Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau,

in Ottawa

Canada's Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau,

in Ottawa

A report

from Timothy Porteous, Prime Minister Trudeau's Executive Assistant

who was present during the meeting between John, Yoko

and the Right-Honourable Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

The

meeting on December 23, 1969 between John Lennon, Yoko Ono, Pierre Elliott

Trudeau and me would not have happened without the late Jim Davey, and I

dedicate this mini-memoir to him. Jim, who had been one of Trudeau’s earliest

supporters, was a policy advisor in the Prime Minister’s Office. He had

seven teenage children and was an enthusiastic fan of John Lennon and the

Beatles. It was Jim who proposed to the Prime Minister’s senior staff that

we arrange a meeting between the Prime Minister and the Lennons.from Timothy Porteous, Prime Minister Trudeau's Executive Assistant

who was present during the meeting between John, Yoko

and the Right-Honourable Prime Minister, Pierre Elliot Trudeau.

In 1969 the Cold War had divided the world into two nuclear-armed rival camps competing for global dominance. Each believed the other was planning to destroy it. In this volatile situation John Lennon apparently decided that the celebrity he had earned as a songwriter and performer could make him an effective advocate for peace. In the spirit of the decade, peace was to be achieved by the relaxation of tensions between individuals, leaders and nations.

Since Trudeau’s childhood music and the other arts had been part of his life. His mother founded a club called Les Amis de l’Art and often invited artists to their home. Trudeau’s taste in music was eclectic. I remember him enjoying concerts by Lighthouse, Ian and Sylvia and the Modern Jazz Quartet. He also enjoyed the company of musicians. Among his friends were Leonard Cohen, Barbra Streisand, Liona Boyd, Jena-Pierre Rampal and Guy Beart.

Trudeau had been concerned about the Cold War long before he became a Member of Parliament and then Prime Minister. He had been a vocal and consistent proponent of nuclear disarmament for Canada and the other nuclear states. Before joining the Liberal party in 1965 he had been critical of Lester Pearson’s decision to accept nuclear warheads on Canadian missiles. As Prime Minister, he made every effort to improve relations between the nuclear powers, culminating in 1983-84 in a round of visits to major heads of government with a comprehensive set of proposals to end the Cold War.

For the Prime Minister’s staff the principal objective of the meetings was not the discussion of music or world peace. It was to be a classic example of the political photo-op.

There is a theory among political organizers that if a politician is photographed in the company of a popular celebrity, some of the popularity may rub off on the politician and result in additional votes in future elections. Nobody knows whether this theory works in practice. In 1972 Trudeau came within two seats of losing an election to Robert Stanfield, a politician who had never been photographed with John Lennon or Yoko Ono. But then perhaps there were enough voting John Lennon fans in two of the seats to make the difference. Who knows?

Jim Davey’s proposal was approved by the senior staff (of whom I was one) and, with the Prime Minister’s agreement; a meeting was scheduled to consist of 15 minutes of conversation and 15 minutes of photography. Rock stars and Prime Ministers have crowded schedules, often booked months or years in advance. For the Prime Minister Christmas week is more relaxed than usual since the Members of Parliament have gone home to their constituencies and there are no meetings of Parliament or the cabinet. So the meeting with the Lennons was arranged for the morning of December 23. (It is also a slow news period, increasing the chances that the resulting photos would be widely and prominently published.)

Since the Prime Minister was sworn in on April 20, 1968, I had served as Special Assistant in charge of speeches and public statements. I had met Trudeau in 1957 and traveled with him in West Africa, the South Pacific and all the provinces and territories of Canada. He was aware of my interests in song writing, theatre and music. As I had not been involved in making the arrangements for the meeting, I was surprised but delighted when he invited me to be the fourth participant.

Special thanks to Timothy Porteous for providing us with this lovely photo!

As I remember it, the meeting started almost on time but it lasted well beyond the scheduled fifteen minutes. This is an indication that Trudeau was enjoying himself since a Prime Minister can end a meeting whenever he wants. (When I became Executive Assistant in 1970, one of my functions was to "interrupt" meetings that were running overtime, a frequent occurrence.)

The time passed very quickly. In an interview Yoko Ono acknowledged that Lennon was nervous, but to me he seemed quite at home. He was utterly charming, highly articulate, an amusing raconteur and, as you would expect, very entertaining. He spoke with a delightful “scouse” accent, which you could cut with a knife and spread on your crumpet. Trudeau, unusually for a politician, was a man of few words, but what he said was always interesting and to the point. Yoko Ono, spoke very little and, when she did, it was to support her husband. My own role was to keep the conversation going in case of awkward pauses, but, since we were all on the same wavelength, it wasn’t difficult to do.

After 33 years it is not possible to recall the details of our conversation. As is usually the case when strangers meet, there was an exchange of personal information.

It is likely that we talked about In His Own Write as it was Lennon’s best-known non-musical, solo creation. I may have mentioned the book to Trudeau, although I doubt if he was familiar with its contents.

Most of the conversation dealt with the world situation and Lennon’s campaign for peace. Although Lennon and Trudeau adopted very different approaches to dealing with the problems of the Cold War, they were in agreement on its fundamental nature. In addition, to threatening the future of the planet and its inhabitants, the conflict was irrational. Neither side could achieve a victory without suffering unacceptable damage to its own population and territory. Somehow a climate of mutual trust had to be created in which disarmament and peaceful diplomatic relations could begin.

As the photographs indicate, our conversation ended with expressions of friendship and mutual respect. Lennon said, “If all politicians were like Mr. Trudeau, there would be peace.” Trudeau said, “I must say that Give Peace a Chance has always seemed to me to be sensible advice.”

Had he lived, Lennon would undoubtedly have supported Trudeau’s peace initiative of 1983-84.

As far as I remember, Lennon did not give Trudeau a symbolic acorn at their meeting. I do not know if he sent one to Trudeau at some other time.

I was not involved in arranging the meeting with John Munro but I expect it was organized by the Prime Minister’s office, possibly at Munro’s request. Munro was the Member of Parliament for a Hamilton constituency and the Minister of Health and Welfare. The LeDain Commission, which was considering the legalization of marijuana, reported to him. Lennon’s views on the effects of drug use would have been of interest to Munro - and there were lots of John Lennon fans in Hamilton.

Timothy Porteous

November 8, 2002.

-- Thanks, Timothy, for your lovely write-up!

PHOTO #1

Photo #1:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-175745 / Serial: PA-175745

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-175745 / Serial: PA-175745

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

Photo #2:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-110805 / Serial: PA-110805

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-110805 / Serial: PA-110805

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #3

Photo #3:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-180804 / Serial: PA-180804

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko Ono at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-180804 / Serial: PA-180804

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #4

Photo #4:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-180804 / Serial: PA-180804

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-180804 / Serial: PA-180804

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #5

The CBC News did a lovely

in-depth report on Prime Minister Trudeau. Please click on the following active

link for their write-up entitled: "One of Our Best and

Brightest"

Photo #5:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-175744 / Serial: PA-175744

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Parliament Hill. 23 decembre 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Parliament Hill, Ottawa. 23 December 1969

Auteur: Duncan Cameron

Photographer: Duncan Cameron

Cote: PA-175744 / Serial: PA-175744

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

Special thanks to Lynn Farrell of

the Montreal Gazette for allowing

the Ottawa Beatles Site to e-publish the following photos taken by Tedd Church.

It is deeply appreciated, Lynn! Also, towards the end of my research for this

project, I discovered that the Montreal Star, a second newspaper company that

took some photos of the event, went out of business on October 25, 1979. Two

photographs listed in numbers 6 and 15 were done by Edward Morris of the

Montreal Star. The National Archives of Canada has retained the negatives

and therefore the photos fall under the guise of archival material. You

cannot not reproduce any of these photos anywhere on the internet without first

obtaining permission from the National Archives of Canada and from the Montreal

Gazette. See details on copyright notice at the end of this page.

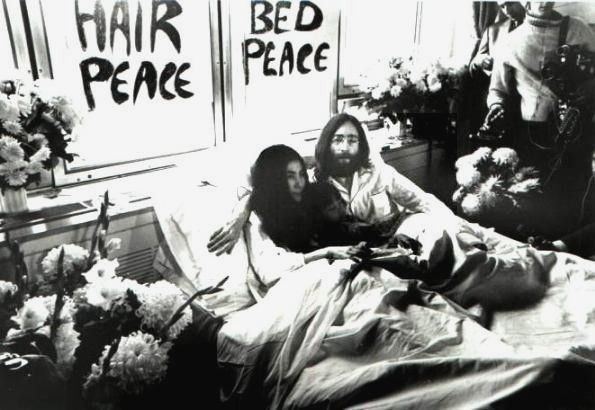

John and

Yoko "Bed-in" at the

Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal

Beatlology

Magazine did an excellent interview with André Perry, who, as most Beatle fans

know, produced the famous "Give Peace A Chance" anthem for John and Yoko. The

interview was conducted by Andrew Croft, Publisher of Beatlology Magazine. In

order to help make this a more complete report for this page, the Ottawa Beatles

Site called upon Andrew Croft's generosity for which we are most grateful in

allowing us to re-print his excellent article from the May/June 2001 Beatlology edition. Thank you,

Andrew!Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal

The Recording of Give Peace A Chance

If you look on the label of every record released by The Beatles you'll see 'Recorded in England' but you won't see anything about when and where the recording was made. With the recording of Give Peace A Chance at the end of John and Yoko's 1969 Bed-in for peace 'tour' a young record producer from Montreal, Quebec, Canada, was called in to record a song in a hotel room where they were holding their 'event'. Not only was he included on the label, but the name of his studio and its address were also included -- his recording career would never be the same.

BM: What was your background in the music industry?

AP: My background is that I was originally a jazz musician, producer and owner of a recording studio in Montreal, called Les Studios André Perry.

BM: How old were you at the time?

AP: I must of have 27, 28.

BM: And how did you come to be involved in this particular recording? Was anyone at EMI involved in contacting you?

AP: Oh yeah, I got a call from EMI, I used to do a lot of work for them in those days and I was starting to do quite a bit of international work at that time. So when they requested, I imagined through EMI, uh, Toronto I think, and Montreal also, who should they call, or who should do the job? I was called to do it.

BM: It has been said that a lot of equipment was shipped from Toronto to do this. Can you tell us a bit about what equipment was used?

AP: No equipment from Toronto was shipped at all. I think the confusion is that I was also doing Tommy (the rock opera) with the Ballet Canadien at Le Place des Arts and they wanted to do this on a 4-track, because in those days 16-track was rare. So we were doing this on 4-track and unfortunately my 4-track was in Le Places des Arts for Tommy. What happened is, I rented from RCA Victor here, a 4-track.

BM: What equipment was involved?

AP: Just a small Ampex board which I had in those days, just four channel in, two channel out. It was recorded on a 4-track Ampex with four microphones -- one for John and his guitar, one for Tommy (Smothers) and two for the room.

BM: How many takes were involved with the taping?

AP: Well, that's a bit of a mystery, because as I remember there was a run-through just for a sound check. And I think that was broken up also, because John wanted Tommy to play, to do different things. And I think that was it. Then we went right into it. One run-through then one take.

BM: Must have been quite exciting.

AP: Well, too much was happening to be exciting. We were a lot more worried about the bad conditions, the room, you know it was very, it was a hotel room all made of gyprock you know, and that resonates as you well understand. And the ceiling was extremely low so there was a tremendous amount of distortion. Everybody was banging on stuff. My worry was to come up with something that was going to be, uh, sound decently. I wasn't that excited.

BM: When the tapes were taken into the studio, how much studio work was involved in preparing a final track for mastering?

AP: Because of the condition of the room being bad, it's as if you put big speakers in such a small enclosure. Too much noise and in a small environment, and what was going on was the tape picking this up. So it wouldn't have been usable. Originally there were no intentions to have any over-dubs done. But when I left John, he looked at me and I said, 'Well, I'll go back to the studio and listen to this and see what it's like.' And then I decided upon myself that the background was a bit too noisy and needed a little 'sweeping.' By this I mean, we kept all the original stuff, we just kind of like, improved it a bit by adding if you like, some voices. So we called a bunch of people in the studio that night, I did, actually that was my decision. And that's probably why John gave me such a credit on the single because I think he thought I took the incentive of doing that. And since it was multi-track I dubbed the original 4-track to an 8-track machine and then used the other 4-track to overdub some voices.

BM: Singers and friends?

AP: Friends, singers. You know -- call everybody -- they showed up. So the next day I went back to John, made a mix of that I went back to him and they moved everybody out of the room and it was just the three of us, with Yoko, and I played it for him and he thought it was wonderful. Kept it 'as is.' There's another story going around about overdubbing in London, England. Nothing was overdubbed in England. The actual '45' that existed originally is the actual recording. There was also in certain books...references to overdubbing in England, that's not true. The only thing that was overdubbed, like I said, is some of these people, and the reason why I did it, is I wanted to give him some kind of option. You see the point of the matter, it's not that we wanted to cheat anything, it was a question of like, not usable, the condition was absolutely terrible. What we did is by taking the original stuff that was there, and just adding a few voices in a cleaner environment, cleaner recording environment. I was just you know, mad it more...(full).

BM: Have you been involved in other Lennon or Beatles-related recordings?

AP: No. I met him again, we saw each other in New York when he couldn't get out of the United States. He couldn't get his green card or whatever it was, and was at a...cocktail party, after an Elton John concert in New York and he remembered everything. He was very sweet to me and he actually apologized to me for not coming to the studio because the studio was getting quite famous. We did Saturday Night Fever and we did David Bowie, The Police, Sting, Roberta Flack. We were doing a lot of Canadian acts, Brian Adams, a group called Toronto, I don't know if you remember (them). Chicago (the group) and I can just go on and on. Cat Stevens -- we did three albums. With Rush we did five albums. So the studio was gaining a world of reputation and, of course, he (John) knew of it, and he has somewhat, I guess in the business, followed it. So he kind of apologized for not coming because he said he could not get out of the United States and I was very touched by that. And he had been extremely generous to me, considering he didn't even know me, but the credit that he gave me on the record of course, helped me a lot. I was young and just starting out. And I thought that was wonderful.

Also, what touched me most was overdubbing, I mean doing the flipside, you know, (Remember Love), with Yoko and him. That was wonderful because I spent about four-and-a-half hours, just the three of us in the room. And at night, so that was much more personal. You know, a bit of a circus, you know.

BM: When did that recording take place?

AP: When we finished Give Peace A Chance, I think as I recall, people hung out for a little bit, and then everybody left, and it was just the three of us. We did that possibly around two o'clock in the morning 'til about four in the morning, or even more than that, actually probably from a little earlier than that, one to three or four in the morning. And that was very nice.

BM: What was the length of the recording time for Give Peace A Chance?

AP: I don't know, but as I recall, I think it must have been around eleven o'clock. But I'm not sure of that. But I know it was fairly late in the evening. Because I showed up I think it was about 5 o'clock, or 6 o'clock in there, to set up. And then people were coming in and out and they were doing interviews...film people also. So as I recall we did it fairly late, ten, eleven, something like that. Because I remember spending the whole night doing the flipside. And we did that very, very fast. As a matter of fact I don't think we even had a playback. There was so many people in the room and it was so noisy and the way I had to record this was with earphones because, you know, I didn't have a control room. There wasn't a room I could set up. You have to take things into perspective, in those days, you're talking a long time ago now. It wasn't like today where you have all these recording tracks and all that. So basically it was quite primitive really. And so it was recorded with earphones even though I had a small pair of speakers for reference but I could not use them because I was in the room with them. I was about twelve feet from the bed. What I like about John was he must have had somewhat of a perception that I was serious and knew what I was doing because he was in full confidence, he didn't know me but he sized me up and he gave me full confidence. I had all this liberty in the world on this thing. It was just totally amazing. 'Cause I remember now, we didn't get a playback. Maybe I might have played it back for him when were in the room by ourselves, I don't remember, probably did. But nevertheless, it's not like he said, 'Well, let's listen to it and let's do it again if it's not right.' He just did it, he looked at me and said 'It's OK?' And that was the end of it. He just sent everybody away.

BM: He wanted to capture the moment?

AP: Well, that was part of it also he wanted some of the mistakes in it and everything. The only reason there was an overdubbed being done was, like I say again, for the distortion that was being created in the room. Otherwise none of this would have been touched.

BM: Do you know if John had any plans to release this as a single immediately or was this something he just wanted recorded for posterity and it happened to become a single?

AP: This was shipped immediately to England to be released.

BM: Do you have any more thoughts on the event, how it impacted you?

AP: For me that wasn't the greatest recording I've ever done because of the conditions. But as far as very proud [I am of] the flip side, because it's a very audiophile sounding kind of recording. Very pure, no EQ, very flat, very sweet, as I must say that's great. I'm very happy I did it, but I think mainly it was more of...Less the circus, you know, I wasn't enchanted with the circus aspect of it. And the circus aspect of it came from the management. It didn't come from John. The management was overwhelmed with what was going on. They were trying to control everything and that part of it was not my 'cup of tea.' When John gave me the credit that he did, we got the call from Toronto saying 'You just won't believe it, we got instructions for international release on the label to say 'Recorded by André Perry, the address, telephone number, the date, where it was recorded.' I said, 'That's incredible!' And I saw some copies of that, from a convention, from South America, different releases and the label reads identical though the rest of the thing is written in Spanish! I was really, really touched by that. I mean I just did what I normally did for anybody -- I would have done the same thing. I was touched that he felt that I guess, that I, what's the word, took on some of the decisions that I did, I don't know exactly where that came from. But he was very generous to me and I was touched by that.

Copyright by Beatlology Magazine, 2001. Used with permission by the Ottawa Beatles Site, November 27, 2002.

PHOTO #6

Yoko and John having a scrum

with media reporters.

Photo #6:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Edward Morris, the Montreal Star

Photographer: Edward Morris, Montreal Star

Cote: PA-152444 / Serial:

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Star; le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Star, the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Edward Morris, the Montreal Star

Photographer: Edward Morris, Montreal Star

Cote: PA-152444 / Serial:

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Star; le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Star, the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

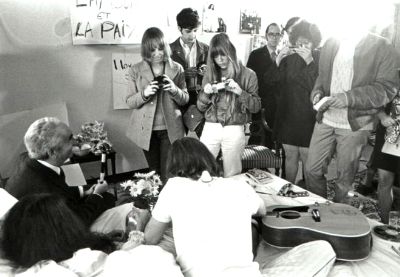

PHOTO #7

The person sitting with his tie

next to Yoko and John is Rabbi Abraham Feinberg

who actually inspired some of the lyrics contained in "Give Peace A Chance".

who actually inspired some of the lyrics contained in "Give Peace A Chance".

Photo #7:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180702 / Serial: PA-180702

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180702 / Serial: PA-180702

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

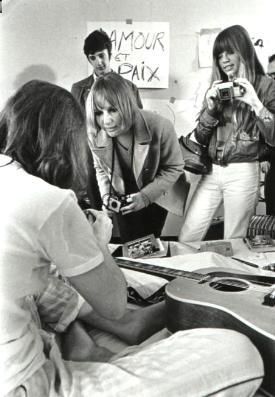

PHOTO #8

Photo #8:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180709 / Serial: PA-180709

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180709 / Serial: PA-180709

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

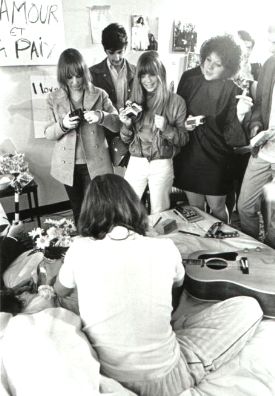

PHOTO #9

Photo #9:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180708 / Serial: PA-180708

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180708 / Serial: PA-180708

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #10

Photo #10:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180703 / Serial: PA-180703

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, The Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180703 / Serial: PA-180703

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #11

Photo #11:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180705 / Serial: PA-180705

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180705 / Serial: PA-180705

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #12

Photo #12:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180706/ Serial: PA-180706

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180706/ Serial: PA-180706

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #13

Photo #13:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180704 / Serial: PA-180704

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180704 / Serial: PA-180704

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #14

Photo #14:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180707 / Serial: PA-180707

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Photographer: Tedd Church, the Montreal Gazette

Cote: PA-180707 / Serial: PA-180707

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Gazette

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

PHOTO #15

Photo #15:

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Edward Morris, the Montreal Star

Photographer: Edward Morris, the Montreal Star

Cote: PA-152445 / Serial: PA-152445

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le, Montreal Star; le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Star; the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

John Lennon et Yoko Ono à l'Queen Elizabeth Hotel. 30 mai 1969

John Lennon and Yoko at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel, 30 May 1969

Auteur: Edward Morris, the Montreal Star

Photographer: Edward Morris, the Montreal Star

Cote: PA-152445 / Serial: PA-152445

Reproduction Interdite Sans Autorisation pour le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

© Copyright 1969 par le, Montreal Star; le Archives Nationales du Canada

© Copyright 2002 par le Site Web Ottawa Beatles

Indeterminate Reproduction in Authorization for the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

© Copyright 1969 by the Montreal Star; the National Archives of Canada

© Copyright 2002 by the Ottawa Beatles Web Site

If John Lennon were alive today,

there is no doubt in my mind that he would have recorded some special tribute in

memory of the fallen lives from the events of the 9/11 tragedy. John would not

have condoned such actions and most certainly would have made that point known

through public statements via the media. I am very pleased that Yoko Ono had the

intuitive insight to release a new re-mixed version of "Give Peace A Chance

2002" which makes lyrical references to the 9/11 tragedy. In spite of all the

crazy antics that both John and Yoko did in the late '60s, their "Give Peace A

Chance" anthem did hit a nerve with many of the youth from that time. Their

actions did put pressure on the United States government to eventually end the

Vietnam War. And, it is in keeping with that spirit of John Lennon

and Yoko Ono, that we have presented these photos here for you to view. God

bless you both and remember everyone to "Give Peace A Chance!"

-- John Whelan, Chief Researcher

for the Ottawa Beatles Site, November 27, 2002.

Click on the "Peace Symbol" for a free downloadable copy

of Yoko's "Give Peace A Chance 2002" from Mindtrain Records!

Other

Canadian web sites chronicling John and Yoko's visits to Canada (Nota Bene:

The Ottawa Beatles Site is not responsible for the content of the first four

external sites)

CBC News in-depth: John and Yoko's Year

of Peace

Richard Maxwell's Live Peace In Toronto,

1969

A Beatles magazine for fans and collectors around the world: Beatlology

Roy Kerwood's rare photos of John and Yoko's Montreal "bed-in" (in

colour!)

The Ottawa Beatles

Site: The Ballad of John and

Yoko in Ottawa

COPYRIGHT NOTICE REGARDING THE

PHOTOS:

1) The photos used in this pictorial essay cannot be displayed freely on the internet (or intranet) without first obtaining permission from the Montreal Gazette and the National Archives of Canada (who also controls the Montreal Star and the Duncan Cameron collection);

2) Any web site owner who displays these photos knowingly without first obtaining permission from the Montreal Gazette and the National Archives of Canada will be subject to legal prosecution to the furthest extent of law by the Montreal Gazette and the National Archives of Canada;

3) And, furthermore, no part of the publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without first prior written permission of the exclusive copyright owner(s) and the publisher of this site;

4) All photos, including the ones from the Montreal Gazette, the Montreal Star and the Duncan Cameron collection are on file at the National Archives of Canada.

---------

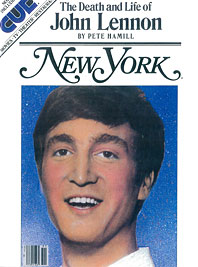

June 8, 1980 John Lennon was shot to death

outside his New York City apartment building as he and his wife, Yoko Ono, were

returning from a recording session. Mark David Chapman shot Lennon only hours

after Lennon had autographed the album Double Fantasy for the 25-year-old

drifter. Chapman was later convicted of the killing and sentenced to

20-years-to-life.

---------------

John

Lennon and Yoko Ono meet Canadian prime minister Pierre Trudeau

John

Lennon and Yoko Ono's 1969 peace campaign came to a close on this day

following a meeting with Canada's prime minister Pierre Trudeau. The meeting took place in the Centre Block on Parliament Hill in Ottawa. Lennon and Ono had arrived in the city at 2am that morning, having travelled from Toronto via Montreal.

They arrived at the Parliament Building at 11am, with a scrum of photographers ready to snap the moment they met the Canadian premiere. It was the only time Lennon and Ono were able to take their peace campaign directly to a world leader.

The meeting lasted for 51 minutes behind closed doors, although news cameras were on hand before and after. When they emerged, a reporter asked Lennon and Ono what had taken them so long. Ono replied that it was because they had all been enjoying the conversation.

Lennon added: "We spent about 50 minutes together, which was longer than he had spent with any head of state. If all politicians were like Mr Trudeau there would be world peace."

The couple also met health minister John Munro for almost two hours before flying back to Toronto, and from there to London, later that day.

--------------------

The Death and Life of John Lennon

|

1. I READ THE NEWS TODAY (OH BOY)

Well nobody came to bug us,

Hustle us or shove us

So we decided to make it our home

If the Man wants to shove us out

We gonna jump and shout

The Statue of Liberty said, “Come!”

New York City . . . New York City . . .

New York City . . .

Que pasa, New York?

Que pasa, New York?

—John Lennon, 1972*

The news arrived like fragment of some forgotten ritual. First a flash on television, interrupting the tail end of a football game. Then the telephones ringing, back and forth across the city, and then another bulletin, with more details, and then more phone calls from around the country, from friends, from kids with stunned voices, and then the dials being flipped from channel to channel while WINS played on the radio. And yes: It was true. Yes: Somebody had murdered John Lennon.

And because it was John Lennon, and because it was a man with a gun, we fell back into the ritual. If you were there for the sixties, the ritual was part of your life. You went through it for John F. Kennedy and for Martin Luther King, for Malcolm X and for Robert Kennedy. The earth shook, and then grief was slowly handled by plunging into newspapers and television shows. We knew there would be days of cliché-ridden expressions of shock from the politicians; tearful shots of mourning crowds; obscene invasions of the privacy of The Widow; calls for gun control; apocalyptic declarations about the sickness of America; and then, finally, the orgy over, everybody would go on with their lives.

Except . . . this time there was a difference. Somebody murdered John Lennon. Not a politician. Not a man whose abstract ideas could send people to wars, or bring them home; not someone who could marshal millions of human beings in the name of justice; not some actor on the stage of history. This time, someone had crawled out of a dark place, lifted a gun, and killed an artist. This was something new. The ritual was the same, the liturgy as stale as ever, but the object of attack was a man who had made art. This time the ruined body belonged to someone who had made us laugh, who had taught young people how to feel, who had helped change and shape an entire generation, from inside out. This time someone had murdered a song.

And it had happened in a city to which that artist had come in order to be private, in order to be safe. It had happened in New York.

¿Qué pasa, New York?

2. IMAGINE ALL THE PEOPLE

If you had the luck of the Irish,

You’d be sorry and wish you were dead. . . .

—Lennon and Ono, 1972

So we all went to the Dakota. We had nowhere else to go. Yes: If you’ve been trained as a reporter, you’re supposed to go places with a cold eye. But I’m sorry; even as the flood tide of rage receded, the cold eye wasn’t possible. Not for John Lennon. Our lives had intersected at critical moments since the winter of 1963, that bitter season after Dallas when people my age realized that they would never again be young. We met in London, in an upstairs joint called the Ad Lib. I was with Al Aronowitz. Ringo and Paul were there too, and later the Stones came in, and we were all at a big table, with music pounding, and girls crowding around, and Brian Jones all blond and small getting drunk on whiskey in a pool of solitude. John Lennon came in after a while with Brian Epstein and sat down next to me. Aronowitz was telling them they had to listen to Dylan, and McCartney was nodding, agreeing with Aronowitz, while Mick Jagger got up to dance with a young blonde wearing too much makeup.

“To hell with Dylan,” Lennon said. “We play rock ’n’ roll.”

“No, John, listen to him,” Aronowitz said. “He’s rock ’n’ roll too. He’s where rock ’n’ roll’s gonna go. Listen.”

Lennon’s mouth became a tight slit, “Dylan, Dylan. Give me Chuck Berry, Give me Little Richard. Don’t give me fancy crap. Crap, American folky intellectual crap. It’s crap.”

He was snarling and bitter and hard. He didn’t want to talk about music. He didn’t want to talk about writing. He looked down the table at Keith Richard. “What the hell are the Yanks here for?” he said, Richard smiled and shrugged. McCartney reached over and touched John’s hand. “Ach, come off it, John,” he said. Lennon pulled his hand away and turned to me.

“Why don’t you f - - - off,” he said. “Why don’t you just get the hell out of here.”

“Why don’t you make me?” I said.

“Hey, come on,” Aronowitz said. “Let’s just have a good time.”

“What?” Lennon said to me.

“I said you should try to make me get out of here.”

He stared at me, and I stared back. The Irish of Liverpool challenging the Irish of Brooklyn. The music pounded, and then, as if he had seen something that he recognized, he smiled and broke the stare and peered into the bottom of his glass. “Yeh, yeh, yeh,” he said quietly, and the moment of confrontation passed. John Lennon left with Brian Epstein. I left with the hatcheck girl. It was all a long time ago. That jagged London evening was part of the baggage I carried down to the Dakota, just as hundreds of others carried their own special visions of John Lennon with them to the high iron gates of 72nd Street. There was no plan, no public announcement of assembly: People just seemed to appear, as if taken through the soft night air by the tug of the past. These were not the people you see at plane crashes, or at giant fires, the injured geeks of the dangerous city. These were people who might come together to mourn the smashing of a work of art. They hugged one another, they shook their heads in sorrow, but, to be truthful, there was not much crying. As writer Peter Hellman said, “Beatle music is somehow just not made for tears.”

There was little rage either, as if the anger had been exhausted in those first shocking moments, and now there was only the need to express silent witness. By two in the morning, the crowd was singing: “All we are saying is give peace a chance.” It was the most simple statement to come out of a terrible time, and I’d heard it sung once by 500,000 people, covering the hills of Washington during one of the anti-war moratoriums, when Richard Nixon was barricaded in the White House behind a line of buses. Here at the Dakota, one woman even knew the verse:

Bagism, Shagism, Dragism, Madism,

Ragism, Tagism,

This-ism, That-ism, Is-m Is-m Is-m

All we are saying. . .

By morning, the gates of the Dakota looked like the wall of a Mexican church, or an instant Lourdes, covered with a collage of flowers, messages, photographs, drawings. The crowd had been brought together as if to some new Holy Place, expressing a deep primitive need to mourn. The mourners were not kids, either. I saw men in raincoats come by carrying briefcases, sealed into lives of business and marriage, the sixties part of some golden adolescence, and one at a time, they stood there on the corner, out of the vision of the TV cameras, and, unlike the people of the night before, wept openly while Beatles music played from dozens of radios. The music seemed elegiac now, all those songs that never went away and probably never will. But now one thing was absolutely certain: John Lennon was dead, and so were the Beatles. They would never come back now. They would never fill a stadium again, never journey all the way back to the years when they changed the English-speaking world and the rest of the world that didn’t know the meaning of “Yeh, yeh, yeh.”

“They were the first people I ever heard of who made me want to be a musician,” a young guitar player said to me. “I was about eight years old, and I heard them, and I knew that I wanted to do that. Maybe not that, Something like that.”

I looked up at the Dakota, its great bulk looming ominously against the rain-swollen morning sky. Up there, five years ago, I’d sat with John Lennon and talked away some hours. His feet were bare that morning, his arms thin under a rumpled T-shirt, his delicate fingers wrapped around a brown-papered cigarette. He was drinking coffee. There was a white Steinway baby-grand piano in a corner of the large living room, a drawing by de Kooning on the wall, some cactus plants; through the window we could see the Essex House, the Americana Hotel, and the spire of the Chrysler Building peeking over the top of the Pan Am Building.

“I never see myself as not an artist,” he said to me that morning. “I never let myself believe that an artist can ‘run dry.’ I’ve always had this vision of bein’ 60 and writing children’s books. I don’t know why. It’d be a strange thing for a person who doesn’t really have much to do with children. I’ve always had that feeling of giving what Wind in the Willows and Alice in Wonderland and Treasure Island gave to me at age seven and eight. Those books opened my whole being.”

He had just come through a difficult personal time during which he had questioned everything about his life and his work and his celebrity.

“What is it I’m doing?” he said, dragging on the cigarette, explaining the questions he had asked himself. “What am I doing? Meanwhile, I was still putting out the work. But in the back of my head it was that: What do you want to be? What are you looking for? And that’s about it. I’m a freakin’ artist, man, not a f - - - - - ’ racehorse.”

Within months of that interview, the man who had said he didn’t really have much to do with children learned that he was going to be a father. And soon he disappeared, making no public music for half a decade, dropping out of the visible world to give his son, Sean, a childhood. Once, during that period, I dropped him a casual note, telling him that if he felt like talking, he should call. I got a form letter back.

John Lennon had silenced himself, perhaps for good. Then, last summer, the news broke that he was back in the studio. I was in London, and the session was over by the time I got home. I’m sorry about that. I wanted to see him one more time, and thank him for showing up. He wasn’t just another racehorse.

3. HELTER SKELTER

In case of accidents he always took his mom.

He’s the all American bullet-headed saxon mother’s son.

All the children sing

Hey, Bungalow Bill

What did you kill

Bungalow Bill?

—Lennon and McCartney

John Lennon was dead by the time Patrolmen James Moran and Bill Gamble got him to Roosevelt Hospital, but the doctors tried anyway. They opened him up. They massaged his heart. There was blood everywhere, but they tried. And while they worked, the scene outside turned into an obscene festival. The paparazzi, thieves of the mojo, arrived by the dozens, waiting to steal the spirit of anyone left alive; legitimate reporters and photographers were there too, and a lot of cops, and then, slowly, as the word spread, a few fans. Some of the reporters fought for the two telephones in the emergency room, while the usual assortment of damaged human beings—older black people, too many children, a Hare Krishna couple—waited to be helped. A woman TV reporter marched in with a crew and tried to walk through the doors to the room where the doctors had been working on John Lennon. She was stopped, of course, but tried to make common decency into a First Amendment issue by ordering the crew to turn on the lights and videotape the refusal of the hospital assistant to allow her to photograph the holes in John Lennon’s chest.

“You want me to tell you what happened, man?” an orderly said, standing outside on an overhang, looking at the crowd. A few fans had lit candles now. “Where’s $20? Come on. Why should I be doing anything for you for nothing?”

Another said, “They did more for Lennon than we normally do for anybody. They cracked his chest open and then tried internal cardiac massage. But nothing helped. He just bled to death.”

Somebody asked whether Yoko Ono was crying as she waited inside with record producer David Geffen and others for the inevitable to happen. “No, she wasn’t crying,” an attendant said. “She’s got $30 million coming to her. Do you blame her for being so cool?”

Inside, Stephan Lynn, the director of emergency services, finally gave up. The official moment of death was recorded as 11:15 P.M.

The body was wrapped and taken to the morgue wagon. When a police car came out of the basement drive, its lights twirling in the signal of distress, and the photographers saw the morgue wagon behind the squad car, there was another scramble. The photographers followed the wagon up the block and then stopped as it pushed out into the city. Yoko wasn’t in it. Got to get Yoko. Yoko’s grief. They did and then left. The parking lot seemed desolate. A man named Eduardo was among those left behind. He was well dressed, middle-aged, and someone asked him why he was there.

“If the Jews had a Christ, the Christians had John Lennon and the Beatles,” he said. “I’m proud to have belonged to the sixties.”

At the morgue, the entrance was sealed shut with a lock and chain. Attendants with green mortuary masks moved around in dumb show, their words inaudible, or typed out forms on grim civil-service typewriters. Behind them, in a refrigerator, lay the sixties.

4. THE LONG AND WINDING ROAD

The long and winding road that leads to your door,

Will never disappear, I’ve seen that road before

It always leads me here, lead me to your door.

—Lennon and McCartney

His name was Mark David Chapman. The pictures show us a suety little man, with a small nose, porky jowls, lank hair flopped forward. Those pictures, drawn on the run while Mark David Chapman was being arraigned for homicide, don’t tell us what was teeming around in his brain. Neither do the details of his life.

“He was a people person,” said Paul Tharp, community-relations director of the Harold Castle Memorial Hospital, in whose printshop Chapman had worked for two years. “He was a man who liked to be with people, and got along well with co-workers. He was a good worker and a go-getter. He was an all-around good guy.”

Yeah—and the details of his life tell us other things. That he was born May 10, 1955, in Fort Worth, Texas; that his father was named David Curtis Chapman, originally of Connecticut, then an air-force sergeant stationed at Carswell Air Force Base; that his mother was Diane Elizabeth Pease Chapman, from Massachusetts; that he was brought up in Decatur, Georgia; that his father left the air force to work for an oil company, then a bank in Atlanta, and that along the way he had taught his son how to play a box guitar.

The details tell you all of that, and how young Mark David Chapman collected Beatles records, graduated from Columbia High School in Decatur, Georgia, where he briefly played guitar in a rock band, went to work for the YMCA, and in 1975 traveled to Beirut at his own expense to work in the YMCA’s International Camp Counselor program, was caught in the Lebanese civil war, escaped death, and returned to Fort Chaffee, Arkansas, to help process refugees from Vietnam.

“The staff was pretty close,” said Gregg Lyman, who worked at Fort Chaffee with Chapman and now lives in Oak Park, Illinois. “We talked a lot about music, rock ’n’ roll. Mark came to my apartment and looked at my record collection and picked up an Allman Brothers album. I guess you can’t live in Georgia without being an Allman Brothers fan. But I can’t really recall any specific comments about the Beatles or John Lennon. Mark really wasn’t into the Beatles that deep.”

Chapman apparently used a lot of drugs in high school, but, according to Lyman, that phase was over by the time he got to Fort Chaffee. “He was the straight member of the group. I knew he had Christian convictions. We’d all be having drinks, and he’d be sitting there with a Coke.” Rod Riemersma, who was also at Chaffee and is now executive director of the Lamar YMCA branch, in Baton Rouge, agreed. “He was more straitlaced than we were,” he said. “If I told an off-color joke, he’d give me a little smile, and I’d lay off out of respect for his feelings.” Chapman had become deeply involved with Christianity in the last two years in high school, carrying around his own personal Bible and making entries in a “Jesus notebook.” Riemersma said that he and Chapman stayed in touch for a couple of years after the Fort Chaffee project, “and he concluded his letters to me with a quote from the Bible or a music lyric.”

Lyman said that Chapman grew very close with a young Vietnamese kid at camp. “The child would do what he could to help Mark,” he said, “sweep out his room, that sort of thing. Mark would sit him on his lap and talk with him, even though the child couldn’t understand what he was saying. Mark was very sad about the departure of that child. We let him lean on us that week.”

Chapman confessed some deeper troubles to another staffer named David Moore, now the 40-year-old executive director of the Duncan YMCA, in Chicago. They shared a room at Fort Chaffee.

“He was in the drug scene and had done some barbiturates and amphetamines and maybe even heroin,” Moore said. “But then he met this woman who changed his life. He was madly in love with Jessica, and she kind of straightened him around. She made him a Christian.” Under her influence, he enrolled in Covenant College, in Lookout Mountain, Tennessee. But he couldn’t hack it, either at college, where he flunked out after a semester, or with the girl, who soon left him. “He was a real bright kid who just didn’t have the discipline,” Moore said. “And he was in love with this woman. But he became unglued when he couldn’t cut it in school, and the girl told him to pack off.” Then he added, “He blamed it on himself, the breakup. He tended to blame himself for everything that went wrong. In clinical terms, he had a very low self-image. The girl was very nice: young, cute, a devout Christian. She is going through hell now more than anyone.”

Failure attaches itself to some people like an odor, and finally Mark David Chapman carried his failure with him to the sunny reaches of Hawaii. We know that in May 1977 he applied for a Hawaii driver’s license, describing himself as five-foot-eleven, 170 pounds, with brown hair and blue eyes. The 1980 Chapman is at least 30 pounds heavier. He was living then in Kaneohe, a bedroom community on the windward side of Oahu, about eight miles from Honolulu. Here the details blur: He appears to have checked himself into the Harold Castle Memorial Hospital, a small Seventh-Day Adventist institution nestled in a banana grove at the foot of the Koolau Mountains. The hospital has a catchall “human relations” unit to handle a wide range of psychiatric disorders, and there are some reports that Chapman came there because he was suicidal. (Moore saw him in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1978, and he told Moore that he had suffered a nervous breakdown.) By August 1977, Chapman was working at Castle Memorial as a maintenance man, mopping floors, tending the grounds, and then, after Paul Tharp discovered that the young man had a talent for art, he was transferred to the printshop. Most of the work was routine printing of hospital forms, but he also designed some posters. Sometimes, during lunch breaks, he would show his slides, proud of his travels.

By Christmas 1977, he was living in an apartment at 112 Puwa Place in a development called Aikahi Gardens, in Kaneohe, overlooking the Marine Corps Air Station, with a view of the Pacific beyond. The units had Mexican tile floors and, overhead, ceiling fans, and Chapman rented one with three bedrooms and then went around introducing himself as Mark from Fort Worth, Texas. His neighbors were mainly new arrivals, what Hawaiians call malihinis, or transients from the marines. Most were like Chapman in other ways; rootless, on the move, always searching for the one perfect place.

Meanwhile, other events were crowding in on Mark David Chapman. Nearly three years ago, his parents had divorced; he was reported to have been very upset by the news. His mother soon arrived in Honolulu; she was never to leave. During the same period, he met a young Japanese-American woman named Gloria Abe. She had graduated from Kailua High School in 1978 and gone to work in the Waters World travel agency in Honolulu. Chapman met her there. She was then a pretty, gentle girl who weighed about 90 pounds, and was described by a friend as “one of the world’s nicest people.”

They were married on June 2, 1979, at the Kailua United Methodist Church in a ceremony whose details were supervised by Chapman himself. One of the wedding guests remembered. “One funny thing we noticed was that he wouldn’t allow any chairs. He wouldn’t allow anyone sitting. Another thing that really kind of got me was that although it was a formal wedding his mother came in sports clothes. Mark and his mother seemed very close.”

After the marriage, Mark kept Gloria away from her old friends, then got her to quit her job at the travel agency, where she had risen to assistant manager. She took a job in the accounting department at Castle Hospital. In November 1979, Chapman decided to quit his hospital job, and the following month went to work as a $4-an-hour security man at 444 Nahua Street, a palm-encircled condominium between Waikiki Beach and the Ala Wai Canal.

In April, the couple moved to Apartment D2107 on the twenty-first floor of the Diamond Head tower of the Kukui Plaza condominium. They paid $425 a month for one bedroom. Each day Chapman went to work on the 7 A.M.–to–4 P.M. shift at Nahua Street. One of the people he worked for was a man named Joe Bustamante, who said later what everybody else said about Mark David Cha

On October 27, Chapman went to a Honolulu gun shop named J&S Sales, Ltd., a store whose slogan is: “Buy a gun and get a bang out of life!” He bought a five-shot 38-caliber Charter Arms revolver for $169 and added special rubber grips for another $35. The process of buying the gun was simple: He needed only to fill out two forms, one at police headquarters, a block from the gun shop, the second at the gun shop itself. He needed only to produce a driver’s license. No photograph was required.

He apparently borrowed some money from his mother and went to Castle Hospital, where his wife still worked, and borrowed another $2,500 from the credit union. By last Saturday, he was in New York. He had more than $2,000 in cash with him, fourteen hours of Beatles songs on tape, his personal Bible, a copy of J. D. Salinger’s novel The Catcher in the Rye, and the gun. He registerèd under his own name at the West Side YMCA, on 63rd Street, off Central Park West, and paid $16.50 for his room. Those are facts. It’s a fact that the following day he left the Y and checked into an $82-a-night room at the Sheraton Centre—the old Americana, visible from John Lennon’s living room—and said he would pay with a credit card. He went to Room 2730, high above Seventh Avenue. All facts.

But the facts don’t tell us what was in his head. Later, when it was over, psychiatrists theorized about what might have happened. They talked about a man who had been suicidal and then became confused about his identity (in this case thinking that he was John Lennon and that his own wife was Yoko Ono), a man who might, then, commit a murder that was actually a kind of suicide. They discussed a man who had suffered a loss of “ego boundaries,” with the blurring of lines between fantasy and reality that is the mark of the classic schizophrenic. They talked about a man who worshiped stars and could think of no way to become a star himself, except by uniting with a star in violence. They discussed the possibility of a man so crazed with love for John Lennon that the slightest rebuff—a curt word that afternoon, a scrawled autograph—might drive him to kill. They were all theories. Nobody knew for sure.

They did know for sure that Mark David Chapman left Room 2730 of the Sheraton Centre on that Monday, a day soft as spring, and went to 72nd Street. He had taken a long and winding road, from Texas and Alabama, through Lebanon and Arkansas, and all the way from Honolulu. But at last, that night, he arrived at the door. He was waiting there when John Lennon stepped out of his limousine. He was still waiting there when the cops arrived and John Lennon lay dying.

5. WORKING CLASS HERO

When they’ve tortured and scared you for twenty odd years

Then they expect you to pick a career

When you can’t really function you’re so full of fear . . .

—John Lennon

When it was over, when the shots had been fired and John Lennon fell out of the world, the life suddenly assumed the perfection of a novel. The novel would begin in Liverpool, a port city of Irishmen and black seamen and the music of the world, and it would end in another port, in New York, across an ocean.

“In Liverpool,” he said once, “when you stood on the edge of the water, you knew the next place was America.” And America was a specific city, as he once told Jann Wenner: “I should have been born in New York, I should have been born in the Village, that’s where I belong.”

But it was Liverpool that gave him life and shaped so much of his art and his person. “I’m a Liverpudlian,” he said to me once. “I grew up there, I knew the streets and the people. And I wanted to get out of there. I wanted to get the hell out. I knew there was a world out there and I wanted it. And I got it. That was the bloody problem.”

He was in New York when he talked about it, long after the Beatles, in some ways long after all the things that had made him unique. And still he went back in talk to Liverpool.

“Yeah, I’d sit in Liverpool and dream of America,” he said. “Who wouldn’t? America was Chuck Berry, the Leonardo of rock ’n’ roll. America was Little Richard, and ‘Johnny B. Goode’ and ‘Be-Bop-a-Lula’ and ‘Good Golly Miss Molly’ and girls with big tits. Now sometimes I walk around the docks on the West Side and I think about Liverpool. The people I went to school with. Lads full of talent and hope and all that crap. And even then, when we were just all startin’ out, they decided to go to work, to go to a job, to work in some bloody office, and I would see them, and they’d be old eighteen months later. Old. Just hunched up, like, walkin’ like their fathers, or if they were women, like their mothers. They were young, like us, and then—” he clapped his hands together sharply “—then they were old. And some of them were pissed at us, because they thought they could’ve become Beatles too. And maybe they were right. But they didn’t. They decided to die early. And I saw them, and I knew that whatever the hell happened, I wasn’t plannin’ on dyin’ in a bloody office.”

pman. It’s what people always say when you knock on their doors after a homicide: “He was quiet. He never did anything unusual to make you think he would do something like that. You never had any trouble with him. I would have hired him again.” He thought for a moment. “He was a normal, regular guy. Everybody liked him.”

One day in October, Chapman told Bustamante he wanted to quit because he had to make a trip to London. He worked his last shift on October 23, breaking in his replacement, a tall, russet-haired man named Mike Bird. That day he walked through his rounds with another name on a piece of paper taped over his brown-and-white plastic name tag. He also signed that name into the building’s logbook, in high, angular letters that appeared to have been crossed out. The name was John Lennon.

“I showed them how to play ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ and told them the words,” McCartney told writer Hunter Davies. “I remember this berry old man getting nearer and breathing down my neck as I was playing. ‘What’s this old drunk doing?’ I thought. Then he said ‘Twenty Flight Rock’ was one of his favorites. So I knew he was a connoisseur.”

A week later, John asked Paul to join the Quarrymen. Within a month, the most successful songwriting team in pop-music history had begun to work together. John had taught himself to pick his way all the way through Buddy Holly’s “That’ll Be the Day,” and their first songs were rehashed Holly. But they had begun. A year later, McCartney brought around a younger friend named George Harrison. He was only fifteen, a student at McCartney’s school, but he could play. As John Lennon entered the Liverpool Art College, Harrison joined the group. The Beatles were three-quarters there.

The Quarrymen became Johnny and the Moondogs; one of John’s fellow art students, Stuart Sutcliffe, sold a painting for $60, was talked into buying a bass guitar, and immediately joined the band, although he didn’t know how to play. They began to perform in a coffee bar called the Jacaranda Club in 1958, using a man named Tommy Moore on drums; then, changing their name to the Silver Beatles, they played their first tour outside Liverpool, wandering through Scotland. The tour was not a success; they worked in a strip joint; Moore went off to be a forklift operator. Then they picked up Pete Best on the drums, mainly because his mother ran a coffee bar called the Casbah and put them to work. Pete Best and Stuart Sutcliffe were with the band when it traveled to play the Kaiserkeller in Hamburg in the fall of 1960. That gig made them into the Beatles. Sutcliffe fell in love with a woman named Astrid Kirchherr and stayed behind in Hamburg when the job ended, and Ringo Starr later replaced Best. But the craziness had begun. Cynthia Lennon, John’s first wife, remembered it as a wild time.

One night in Hamburg, she wrote later, John “fell about the stage in hysterical convulsions with so much booze and so many pills inside him that he was no way in control. . . . That night ended with John sitting on the edge of the stage in a very unsteady manner with an ancient wooden toilet seat round his neck, his guitar in one hand and a bottle of beer in the other, completely out of his mind.”

Back in Liverpool, their playing seemed harder, more driven than anything else on the British scene. They were in the Cavern Club when Brian Epstein walked in to see their lunch-time show on November 9, 1961. Epstein was then the 27-year-old owner of the Nems Music Store; he was homosexual; he had failed as an artist and had failed during eighteen months as a student at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art. But he became the manager of the Beatles, and his gift for promotion and packaging made them into gigantic stars. He had them clean up their act. He had them trim and shape the long, unruly haircuts, and wear those silly collarless suits (which John hated). He encouraged them to write their own songs. In one sense, John looked at Epstein and found the father he had never had.

“Brian was the only person I ever saw dominate John Lennon,” said attorney Nat Weiss, who later worked for the Beatles. He also thought that Epstein had a crush on Lennon: “I’m convinced that this was the strongest single reason for him wanting to manage the Beatles in the first place. At first, he was very attracted to John.” Later, John would say that he and Epstein never sexually consummated their relationship, but in 1971, four years after Epstein’s suicide, he still talked about him with strong feelings:

“We had complete faith in him when he was runnin’ us. To us, he was the expert. I mean, originally he had a shop. Anybody who’s got a shop must be all right. He went around smarmin’ and charmin’ everybody. He had hellish tempers and fits and lockouts, and y’know he’d vanish for days. He’d come to a crisis every now and then, and the whole business would f - - - - -’ stop ‘cause he’d be on sleepin’ pills for days on end and wouldn’t wake up. We’d never have made it without him and vice versa. Brian contributed as much as us in the early days, although we were the talent and he was the hustler. He wasn’t strong enough to overbear us. Brian could never make us do what we really didn’t want to do.”

PAGE 9

What John Lennon wanted to do was leave Liverpool, make music, get rich and famous, and he did them all. After 1964, his name was known all over the world, and his life was increasingly lived on a public stage. “You see,” he said later, “we wanted to be bigger than Elvis.” They were, but part of John Lennon wanted something else: a purer vision, a harder art, the solitude of the creator. He could never do that as a Beatle, and as their lives careened along, as the touring stopped with the last concert (San Francisco, August 29, 1966), as first John and then the others tripped on LSD, dabbled in mysticism, made elaborate acid music in the studio, and tried to adjust to incredible wealth and fame, Lennon seemed to drift away. He met Yoko Ono, seven years older, a conceptual artist, a challenge, and eventually they all drifted away. After 1970 the Beatles were finished. And John Lennon, of course, continued to make music on his own.