so beautiful

June 19th update

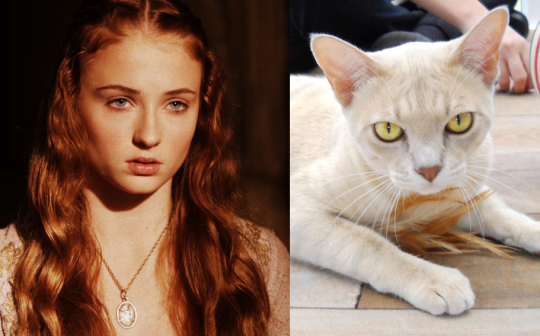

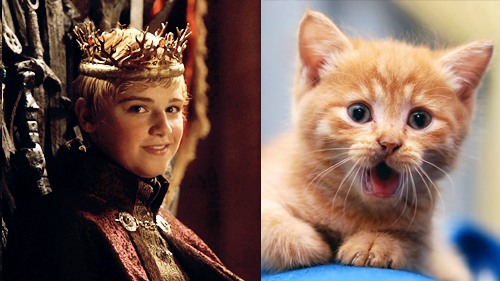

Mews: Game of Thrones Cat Doppelgaenger

Hi everyone,

I came across this brilliant post on a fellow bloggers website and just had to share it with all of you! howtofangirl took the time of putting together this hilarious line-up of a Game of Throne Cat cast!

As a GoT fan I just had to post about this brilliant work.

Daenerys Targaryen

Anya Stark

Jon Snow

Theon Greyjoy

Margaery Tyrell

Sansa Stark

Tommen Baratheon

Tyrion Lannister

Stannis Baratheon

High Sparrow

Cersei Lannister

Jamie Lannister

Jorah Mormont

Roose Bolton

Bran Stark

Melisandre

Brienne of Tarth

Varys

Bronn

Mance Rayder

Grey Worm

Hodor

Littlefinger

And, last but not least, One of Dany’s Dragons

We hope you enjoyed this post as much as we did and don’t forget to tell us your favourite haha.

Not subscribed to our Newsletter yet? Click here!

Thanks,

Marc

----------

--------------

Prime Minister Stephen Harper and our Laureen- we love our cats and dogs in Canada

------------------

When This Homeless Cat

Sneaks Into A Zoo, I Can’t Stop Smiling

-----------------

God bless our troops always

NOVA SCOTIA Still the place of innocence- Al Rest captured this cat sitting an enjoying the view at Halifax Harbour -coolImage

----------------

je suis Charlie

-------------

데이브 [고양이 키울 때 안 좋은점 - 롤 할 때] Playing League with your cat around

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9lxdYVIpM6U

Playing ‘League of Legends’ is way harder with your cat around【Video】

Three things about cats that everyone knows: they are super cute, incredibly contrary, andlove to play League of Legends.

Er… Nope, we didn’t know about that last one either! But as this video of a kitty in South Korea fighting with his owner for screen time shows us, there may be (adorable) downsides to cat ownership we’d never even considered. It turns out, some cats love touchscreen games as much as humans do!

YouTuber Dave from The World of Dave got this tiny rescue kitten from a shelter a few months ago.

He loves to play with toys, chase around pieces of string…and to get between Dave and League of Legends.

▼ “No no no no no no no no…”

▼ HELP!

▼ Wait, is that not what “multiplayer” means…? Perhaps we’ve misunderstood again.

http://en.rocketnews24.com/2015/01/13/playing-league-of-legends-is-way-harder-with-your-cat-around%E3%80%90video%E3%80%91/

------------------

God bless all our Nato troops... and cats and dogs and beautiful creatures-u are loved

-----------

DODGER-

the cat that takes bus and never gets lost-utube

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3AwmiH4KGx8

Owner surprised to find cat regularly catches bus

A pet cat named Dodger is living up to his name - by catching free bus

trips from his home town.

Owner surprised to find cat regularly catches bus

A pet cat named Dodger is living up to his name - by catching free bus

trips from his home town.

Artful Dodger hops off the bus near his home in Bridport, Dorset Photo: Peter Willows/BNPS

9:14AM GMT 15 Dec 2011

The ginger moggy, who was named after the Artful Dodger from Oliver

Twist, has taken to hopping on and off the public transport at the bus station

near his home.

The 15-year-old Tom even sits on bemused passengers' laps as the bus

makes up to 10 mile round trips from Bridport to Charmouth in Dorset.

Dodger is such a regular customer that some of the drivers take tins of

cat food to work with them to give to him. They even know what stop to let him

off at.

At the end of his journeys the roving moggy returns to his home and

owner Fee Jeanes.

Mrs Jeanes, 44, believes Dodger first took a liking to the buses as they

are warm like greenhouses when the sun is on them.

But the adventurous pet has since ended up being taken for several

rides.

Mrs Jeanes, 44, said: "We moved here 19 months ago and our house

backs onto the bus station.

"He is an old boy and is very friendly. At first Dodger kept going

to the bus station because people there fed him tit-bits and scraps of food.

"But then he started climbing on board the buses because they are

almost like greenhouses when it is sunny.

"Then last week I found out he had travelled to Charmouth and back,

which is a 10 mile round trip.

"I hadn't seen him all morning until my daughter Emily told me one

of her friends had just seen him on the bus at Charmouth.

"I couldn't believe it and panicked. I got into my car to go off

and look for him and then at that moment the bus pulled up near our house and

low and behold he got off.

"He had fallen asleep on board and nobody knew about it. When the

driver realised he knew who Dodger was and where he lived and kept him on

board.

"That afternoon I saw Dodger climb on board another bus and I

rushed to tell the driver.

"I was shocked when she told me Dodger was always on there and

liked to sit on the seats because they are warm from where people have been

sitting.

"The drivers buy cat food for him and he sits on people's laps.

"Sometimes he just sits in the middle of the road and waits for the

bus to turn up before he gets on."

Dodger is familiar to regular bus passengers and drivers, but Mrs Jeanes

still receives several calls a week asking if she has lost a ginger cat.

A spokesman for bus firm First said they didn't mind Dodger on their buses

but didn't actively encourage him.

He said: "The drivers have been asked not to feed it because we

recognise that cat has an owner and we do not want to discourage it from

returning home for food and shelter, but in principle we do not have a problem

with it being around the bus station.

"Given this cat is elderly we suspect it would be eligible for free

travel, perhaps a bus puss, if such a thing existed."

---

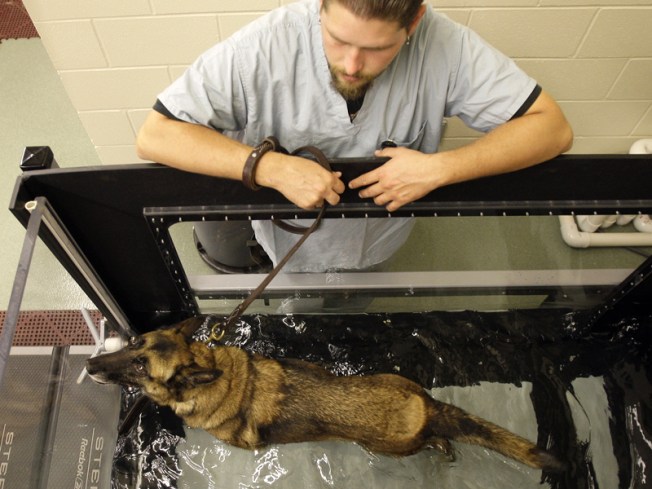

DEXTER- THE DOG WHO SAVED THOUSANDS OF LIVES- NOW A MEMBER OF THE AMERICAN LEGION- A VET IS SAVED....

Dexter the Dog Comes Home a War Hero

Four-legged veteran receives a warm welcome from Legion Post

By Matt Bartosik

Saturday, Dec 20,

2008 • Updated at 6:46 AM CST

Saturday, Dec 20,

2008 • Updated at 6:46 AM CST

A retiring Iraq war veteran has a long list of accomplishments from

his six years of service. He patrolled the streets of Baghdad, suppressed a

prison riot, and detected explosives on a garbage truck destined to detonate at

an American mess hall, thereby saving hundreds of soldiers' lives.

But what's unique about this

particular military hero is the fact that he has four legs.

Military Working Dog Dexter

CO67—Dexter, for short—will live a relaxed life in the far northern suburb of

Spring Grove, thanks to the military organization saveavet.org.

Dexter almost didn't get to enjoy his

retirement. The military had intended to euthanize the dog because he was

having hip problems, and most military and police dogs cannot be adopted due to

their aggressiveness. Kathleen Ellison, his Navy

handler, pleaded with congressmen to save the canine hero.

Ellison got in contact with Debbie Kandoll, who runs

Military Working Dog Adoptions, who in turn found Iraq vet Danny Scheurer, co-founder

of Save-A-Vet. He worked with similar dogs in his basic infantry unit and has

the experience needed to handle a fellow veteran.

"I wouldn't be here if it

weren't for these dogs," 30-year-old Scheurer told the Sun-Times.

"These dogs saved my life."

Later this month, Kandoll and Ellison

will escort Dexter back to the United States from his base in Naples, Italy.

Once in Spring Grove, he will be welcomed by a public ceremony at Fox Lake

American Legion Post 703, where he will become a full-fledged member.

In fact, John Raughter,

communications director for the American Legion National, told the Lake County News Sun that

no other post has ever admitted a working animal.

"The posts are autonomous. They

don't have to ask us for permission," Raughter said.

Jerry Kandziorski, commander of the

post, feels it is only right to induct Dexter.

"We feel he is a military

veteran. He deserves some recognition of his own," Kandziorski explained.

"He spent six years in Iraq, and he deserves this."

Dexter is scheduled to attend his first meeting in

January.

Source: http://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/An-Iraq-War-Hero-like-None-Other.html#ixzz3OjylVLpG

Follow us: @nbcchicago on Twitter | nbcchicago on Facebook

----------------

-----------------

Ultimate Dog Tease- 165,267,247

hits

Uploaded on 1 May 2011

---------------

Cute Giant Cat Japanese Commercial (2014)

-------------

Pet

Corner: The mysterious, elegant world of the cat

PAT LEE

Published January 11, 2015 - 2:38pm

Last Updated January 11, 2015 - 4:45pm

Published January 11, 2015 - 2:38pm

Last Updated January 11, 2015 - 4:45pm

The CBC’s Nature of Things will explore the world of the domestic cat in

The Lion in Your Living on Jan. 15 at 8 p.m.

We are a household that enjoys the company of both cats and dogs.

So we’re well versed in the ways of both camps and always interested in

noting the similarities (all miss us when we’re gone, all like a warm ray of

sun, all like to be underfoot at the most inconvenient time) and the

differences (cats hide when company comes, dogs announce all comings and goings

on the street, cats like to start the day a LOT earlier).

SEE ALSO: Adoptable

of the Week Timber

SEE ALSO:

More Pet Corners

While dogs get the flattering label Man’s Best Friend, it’s actually

cats who are the No. 1 pet around the world, including Canada. And, as we know,

cats took over the Internet a long time ago.

The fascinating aspects of domestic cats – who researchers have traced

back some 10,000 years ago to Israel – are the focus of this week’s Nature of

Things, which last year took a look at what makes dogs tick.

Airing Thursday at 8 p.m. on CBC, The Lion in Your Living Room takes a

look at the some of the fascinating aspects of cats that anyone who has had the

privilege of being owned by one will recognize.

For example, their different meows. According to professor Karen McComb

of the University of Sussex in the UK, they have learned to manipulate us

through their cat calls, modulating them to get what they want from us, like

breakfast a 5 a.m. Clever buggers.

Her research also found that owners recognize their own cat’s meows over

another cat.

Of course we all know about purring, but turns out there’s different

kinds of that too. And did you know, that cats who roar don’t purr, and vice

versa?

Another interesting segment looks at a cat’s senses, their superior

sense of smell and sight, as well as their unique ability to jump – to the

annoyance of us at times – as well as, perhaps more impressively, fall.

Carlos Driscoll, the researcher who has traced domestic cats back to

their origin, says the story is that cats became part of our lives for rodent

control, a theory he disputes. He believes they were drawn to humans because of

our garbage, a truth to this day for feral cats.

The opportunistic and companionable feline made its way around the world

aboard ships (did you know the Vikings preferred ginger cats?) to become a

mainstay around the globe.

While it started off with classic brown and black tabby markings, the

cat has evolved to have many looks and markings, thanks to man’s intervention.

As the documentary points out, cats are bred purely for looks, not for

purpose, as are many dogs.

Also interviewed is British biologist John Bradshaw, who has written

extensively on the history and behaviour of cats.

He wades into the controversial waters of domestic cats as predators,

the indoor/outdoor debate and discusses ways humans are changing, not always

for the better, the social structure of cats’ lives.

The documentary, produced by Donna and Daniel Zuckerbrot, who also

brought us the similar look at dogs last year, describes cats as “beautiful,

elegant, mysterious.”

We couldn’t agree more.

Pat Lee is a former editor of www.thechronicleherald and a volunteer at

various rescue organizations, including the Nova Scotia SPCA. Follow her on

Facebook at Pat Lee's Pet Corner.

About the Author

------------------

Check out this BOBCAT in Kentville Nova Scotia area.... seriously... Nova Scotia and animals.... check out the bobcat strolling on it's own as the pheasant continues 2 feast in Dr. MacGregor's Wanda's backyard..... seriously..... Foggy the Whale being saved and Grommet the Whale does the dance of joy at humans releasing our Foggy... and couger sighting... and this month is beautiful Mi'kmaq Month in Nova Scotia.... come visit folks... we'd love 2 have u visit.... oh yeah... are u brave enough 2 visit the pumpkin people around kentville and take part in the pumpking sailing races in Windsor.... and we mean sitting in cleaned out pumpkins and ya gotta build it ur own selves etc. (soooo funny and so much October fun in Nova Scotia friends) and actually racing... hey it's a Nova Scotia thing... and we'd love ta have ya visit. Have a great day friends

---------------

The Evolution of House Cats

Published in Scientific America

KEY CONCEPTS

Unlike other domesticated creatures, the house cat

contributes little to human survival. Researchers

have therefore wondered how and why cats came to live among

people.

Experts traditionally thought that the Egyptians were the

first to domesticate the cat, some 3,600 years

ago.

But recent genetic and archaeological discoveries indicate

that cat domestication began in the Fertile

Crescent, perhaps around 10,000 years ago, when agriculture

was getting under way.

The findings suggest that cats started making themselves

at home around people to take advantage of the mice and food scraps found in their settlements.

It is by turns aloof and affectionate, serene and savage,

endearing and exasperating. Despite its

mercurial nature, however, the house cat is the most popular

pet in the world. A third of

American households have feline members, and more than 600

million cats live among

humans worldwide. Yet as familiar as these creatures are, a

complete understanding of their

origins has proved elusive. Whereas other once wild animals

were domesticated for their milk,

meat, wool or servile labor, cats contribute virtually

nothing in the way of sustenance or work

to human endeavor. How, then, did they become commonplace

fixtures in our homes?

Scholars long believed that the ancient Egyptians were the

first to keep cats as pets, starting

around 3,600 years ago. But genetic and archaeological

discoveries made over the past five

years have revised this scenario—and have generated fresh

insights into both the ancestry of

the house cat and how its relationship with humans evolved.

Cat’s Cradle

The question of where house cats first arose has been

challenging to resolve for several reasons.

Although a number of investigators suspected that all

varieties descend from just one cat

species—Felis silvestris, the wildcat—they could not be

certain. In addition, that species is not

confined to a small corner of the globe. It is represented

by populations living throughout the

Old World—from Scotland to South Africa and from Spain to

Mongolia—and until recently

scientists had no way of determining unequivocally which of

these wildcat populations gave rise

to the tamer, so-called domestic kind. Indeed, as an

alternative to the Egyptian origins

hypothesis, some researchers had even proposed that cat

domestication occurred in a number

of different locations, with each domestication spawning a

different breed. Confounding the

issue was the fact that members of these wildcat groups are

hard to tell apart from one another

and from feral domesticated cats with so-called

mackerel-tabby coats because all of them have

the same pelage pattern of curved stripes and they

interbreed freely with one another, further

blurring population boundaries.

In 2000 one of us (Driscoll) set out to tackle the question

by assembling DNA samples from

some 979 wildcats and domestic cats in southern Africa,

Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia and

the Middle East. Because wildcats typically defend a single

territory for life, he expected that

the genetic composition of wildcat groups would vary across

geography but remain stable over

time, as has occurred in many other cat species. If regional

indigenous groups of these animals

could be distinguished from one another on the basis of

their DNA and if the DNA of domestic

cats more closely resembled that of one of the wildcat

populations, then he would have clear

evidence for where domestication began.

In the genetic analysis, published in 2007, Driscoll,

another of us (O’Brien) and their colleagues

focused on two kinds of DNA that molecular biologists

traditionally examine to differentiate

subgroups of mammal species: DNA from mitochondria, which is

inherited exclusively from

the mother, and short, repetitive sequences of nuclear DNA

known as microsatellites. Using

established computer routines, they assessed the ancestry of

each of the 979 individuals

sampled based on their genetic signatures. Specifically,

they measured how similar each cat’s

DNA was to that of all the other cats and grouped the

animals having similar DNA together.

They then asked whether most of the animals in a group lived

in the same region.

The results revealed five genetic clusters, or lineages, of

wildcats. Four of these lineages

corresponded neatly with four of the known subspecies of

wildcat and dwelled in specific

places: F. silvestris silvestris in Europe, F. s. bieti in

China, F. s. ornata in Central Asia and F. s.

cafra in southern Africa. The fifth lineage, however,

included not only the fifth known

subspecies of wildcat—F. s. lybica in the Middle East—but

also the hundreds of domestic cats

that were sampled, including purebred and mixed-breed

felines from the U.S., the U.K. and

Japan. In fact, genetically, F. s. lybica wildcats collected

in remote deserts of Israel, the United

Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia were virtually

indistinguishable from domestic cats. That the

domestic cats grouped with F. s. lybica alone among wildcats

meant that domestic cats arose in

a single locale, the Middle East, and not in other places

where wildcats are common.

Once we had figured out where house cats came from, the next

step was to ascertain when they had

become domesticated. Geneticists can often estimate when a

particular evolutionary event occurred

by studying the quantity of random genetic mutations that

accumulate at a steady rate over time. But this so-called molecular clock ticks

a mite too slowly to precisely date events as recent as the past

10,000 years, the likely interval for cat domestication. To

get a bead on when the taming of the cat

began, we turned to the archaeological record. One recent

find has proved especially informative in

this regard.

In 2004 Jean-Denis Vigne of the National Museum of Natural

History in Paris and his colleagues

reported unearthing the earliest evidence suggestive of

humans keeping cats as pets. The discovery

comes from the Mediterranean island of Cyprus, where 9,500

years ago an adult human of unknown

gender was laid to rest in a shallow grave. An assortment of

items accompanied the body—stone

tools, a lump of iron oxide, a handful of seashells and, in

its own tiny grave just 40 centimeters away,

an eight-month-old cat, its body oriented in the same

westward direction as the human’s.

Because cats are not native to most Mediterranean islands,

we know that people must have brought

them over by boat, probably from the adjacent Levantine

coast. Together the transport of cats to the

island and the burial of the human with a cat indicate that

people had a special, intentional

relationship with cats nearly 10,000 years ago in the Middle

East. This locale is consistent with the

geographic origin we arrived at through our genetic

analyses. It appears, then, that cats were being

tamed just as humankind was establishing the first

settlements in the part of the Middle East known

as the Fertile Crescent.

A Cat and Mouse Game?

With the geography and an approximate age of the initial

phases of cat domestication established, we

could begin to revisit the old question of why cats and

humans ever developed a special relationship.

Cats in general are unlikely candidates for domestication.

The ancestors of most domesticated

animals lived in herds or packs with clear dominance

hierarchies. (Humans unwittingly took

advantage of this structure by supplanting the alpha

individual, thus facilitating control of entire

cohesive groups.) These herd animals were already accustomed

to living cheek by jowl, so provided

that food and shelter were plentiful, they adapted easily to

confinement.

Cats, in contrast, are solitary hunters that defend their

home ranges fiercely from other cats of the

same sex (the pride-living lions are the exception to this

rule). Moreover, whereas most domesticates

feed on widely available plant foods, cats are obligate

carnivores, meaning they have a limited ability

to digest anything but meat—a far rarer menu item. In fact,

they have lost the ability to taste sweet

carbohydrates altogether. And as to utility to humans, let

us just say cats do not take instruction well.

Such attributes suggest that whereas other domesticates were

recruited from the wild by humans

who bred them for specific tasks, cats most likely chose to

live among humans because of

opportunities they found for themselves.

Early settlements in the Fertile Crescent between 9,000 and

10,000 years ago, during the Neolithic

period, created a completely new environment for any wild

animals that were sufficiently flexible and

inquisitive (or scared and hungry) to exploit it. The house

mouse, Mus musculus domesticus, was

one such creature. Archaeologists have found remains of this

rodent, which originated in the Indian

subcontinent, among the first human stores of wild grain

from Israel, which date to around 10,000

years ago. The house mice could not compete well with the

local wild mice outside, but by moving

into people’s homes and silos, they thrived.

It is almost certainly the case that these house mice

attracted cats. But the trash heaps on the

outskirts of town were probably just as great a draw,

providing year-round pickings for those felines

resourceful enough to seek them out. Both these food sources

would have encouraged cats to adapt

to living with people; in the lingo of evolutionary biology,

natural selection favored those cats that

were able to cohabitate with humans and thereby gain access

to the trash and mice.

Over time, wildcats more tolerant of living in

human-dominated environments began to proliferate

in villages throughout the Fertile Crescent. Selection in

this new niche would have been principally

for tameness, but competition among cats would also have continued

to influence their evolution and

limit how pliant they became. Because these proto–domestic

cats were undoubtedly mostly left to

fend for themselves, their hunting and scavenging skills

remained sharp. Even today most

domesticated cats are free agents that can easily survive

independently of humans, as evinced by the

plethora of feral cats in cities, towns and countrysides the

world over.

Considering that small cats do little obvious harm, people

probably did not mind their company.

They might have even encouraged the cats to stick around

when they saw them dispatching mice and

snakes. Cats may have held other appeal, too. Some experts

speculate that wildcats just so happened

to possess features that might have preadapted them to

developing a relationship with people. In

particular, these cats have “cute” features—large eyes, a

snub face and a high, round forehead, among

others—that are known to elicit nurturing from humans. In

all likelihood, then, some people took

kittens home simply because they found them adorable and

tamed them, giving cats a first foothold

at the human hearth.

Why was F. s. lybica the only subspecies of wildcat to be

domesticated? Anecdotal evidence suggests

that certain other subspecies, such as the European wildcat

and the Chinese mountain cat, are less

tolerant of people. If so, this trait alone could have

precluded their adoption into homes. The

friendlier southern African and Central Asian wildcats, on

the other hand, might very well have

become domesticated under the right conditions. But F. s.

lybica had the advantage of a head start by

virtue of its proximity to the first settlements. As

agriculture spread out from the Fertile Crescent, so, too, did the tame scions

of F. s. lybica, filling the same niche in each region they entered—and

effectively shutting the door on local wildcat populations.

Had domestic cats from the Near East

never arrived in Africa or Asia, perhaps the indigenous

wildcats in those regions would have been

drawn to homes and villages as urban civilizations

developed.

Rise of the Goddess

We do not know how long the transformation of the Middle

Eastern wildcat into an affectionate

home companion took. Animals can be domesticated quite

rapidly under controlled conditions. In

one famous experiment, begun in 1959, Russian scientists

using highly selective breeding produced

tame silver foxes from wild ones in just 40 years. But

without doors or windowpanes, Neolithic

farmers would have been hard-pressed to control the breeding

of cats even if they wanted to. It

seems reasonable to suggest that the lack of human influence

on breeding and the probable

intermixing of house cats and wildcats militated against

rapid taming, causing the metamorphosis to

occur over thousands of years.

Although the exact timeline of cat domestication remains

uncertain, long-known archaeological

evidence affords some insight into the process. After the

Cypriot find, the next oldest hints of an

association between humans and cats are a feline molar tooth

from an archaeological deposit in

Israel dating to roughly 9,000 years ago and another tooth

from Pakistan dating to around 4,000

years ago.

Testament to full domestication comes from a much later

period. A nearly 3,700-year-old ivory cat

statuette from Israel suggests the cat was a common sight

around homes and villages in the Fertile

Crescent before its introduction to Egypt. This scenario

makes sense, given that all the other

domestic animals (except the donkey) and plants were

introduced to the Nile Valley from the Fertile

Crescent. But it is Egyptian paintings from the so-called

New Kingdom period—Egypt’s golden era,

which began nearly 3,600 years ago—that provide the oldest

known unmistakable depictions of full

domestication. These paintings typically show cats poised

under chairs, sometimes collared or

tethered, and often eating from bowls or feeding on scraps.

The abundance of these illustrations

signifies that cats had become common members of Egyptian

households by this time.

It is in large part as a result of evocative images such as

these that scholars traditionally perceived

ancient Egypt as the locus of cat domestication. Even the

oldest Egyptian representations of wildcats

are 5,000 to 6,000 years younger than the 9,500-year-old

Cypriot burial, however. Although ancient

Egyptian culture cannot claim initial domestication of the

cat among its many achievements, it surely

played a pivotal role in subsequently molding the

domestication dynamic and spreading cats

throughout the world. Indeed, the Egyptians took the love of

cats to a whole new level. By 2,900

years ago the domestic cat had become the official deity of

Egypt in the form of the goddess Bastet,

and house cats were sacrificed, mummified and buried in

great numbers at Bastet’s sacred city,

Bubastis. Measured by the ton, the sheer number of cat

mummies found there indicates that

Egyptians were not just harvesting feral or wild populations

but, for the first time in history, were

actively breeding domestic cats.

Egypt officially prohibited the export of their venerated

cats for centuries. Nevertheless, by 2,500

years ago the animals had made their way to Greece, proving

the inefficacy of export bans. Later,

grain ships sailed directly from Alexandria to destinations

throughout the Roman Empire, and cats

are certain to have been onboard to keep the rats in check.

Thus introduced, cats could have

established colonies in port cities and then fanned out from

there. By 2,000 years ago, when the

Romans were expanding their empire, domestic cats were

traveling with them and becoming

common throughout Europe. Evidence for their spread comes

from the German site of Tofting in

Schleswig, which dates to between the 4th and 10th

centuries, as well as increasing references to cats

in art and literature from that period. (Oddly, domestic

cats seem to have reached the British Isles

before the Romans brought them over—a dispersal that

researchers cannot yet explain.)

Meanwhile, on the opposite side of the globe, domestic cats

had presumably spread to the Orient

almost 2,000 years ago, along well-established trade routes

between Greece and Rome and the Far

East, reaching China by way of Mesopotamia and arriving in

India via land and sea. Then something

interesting happened. Because no native wildcats with which

the newcomers could interbreed lived

in the Far East, the Oriental domestic cats soon began

evolving along their own trajectory. Small,

isolated groups of Oriental domestics gradually acquired

distinctive coat colors and other mutations

through a process known as genetic drift, in which traits

that are neither beneficial nor maladaptive

become fixed in a population.

This drift led to the emergence of the Korat, the Siamese,

the Birman and other “natural breeds,”

which were described by Thai Buddhist monks in a book called

the Tamara Maew (meaning “CatBook Poems”) that may date back to 1350. The putative antiquity

of these breeds received support from the results of genetic studies announced last year, in

which Marilyn Menotti-Raymond of the National Cancer Institute and Leslie Lyons of the University

of California, Davis, found DNA

differences between today’s European and Oriental domestic

cat breeds indicative of more than 700

years of independent cat breeding in Asia and Europe.

As to when house cats reached the Americas, little is known.

Christopher Columbus and other

seafarers of his day reportedly carried cats with them on

transatlantic voyages. And voyagers

onboard the Mayflower and residents of Jamestown are said to

have brought cats with them to control vermin and to bring good luck. How house

cats got to Australia is even murkier, although

researchers presume that they arrived with European

explorers in the 1600s. Our group at the U.S.

National Institutes of Health is tackling the problem using

DNA.

Breeding for Beauty

Although humans might have played some minor role in the

development of the natural breeds in

the Orient, concerted efforts to produce novel breeds did

not begin until relatively recently. Even the

Egyptians, who we know were breeding cats extensively, do

not seem to have been selecting for

visible traits, probably because distinctive variants had

not yet arisen: in their paintings, both

wildcats and house cats are depicted as having the same

mackerel-tabby coat. Experts believe that

most of the modern breeds were developed in the British

Isles in the 19th century, based on the

writings of English natural history artist Harrison Weir.

And in 1871 the first proper fancy cat

breeds—breeds created by humans to achieve a particular

appearance—were displayed at a cat show

held at the Crystal Palace in London (a Persian won,

although the Siamese was a sensation).

Today the Cat Fancier’s Association and the International

Cat Association recognize nearly 60 breeds

of domestic cat. Just a dozen or so genes account for the

differences in coat color, fur length and

texture, as well as other, subtler coat characteristics,

such as shading and shimmer, among these

breeds.

Thanks to the sequencing of the entire genome of an

Abyssinian cat named Cinnamon in 2007,

geneticists are rapidly identifying the mutations that

produce such traits as tabby patterning, black,

white and orange coloring, long hair and many others. Beyond

differences in the pelage-related

genes, however, the genetic variation between domestic cat

breeds is very slight—comparable to that

seen between adjacent human populations, such as the French

and the Italians.

The wide range of sizes, shapes and temperaments seen in

dogs—consider the Chihuahua and Great

Dane—is absent in cats. Felines show much less variety

because, unlike dogs—which starting in

prehistoric times were bred for such tasks as guarding,

hunting and herding—wildcats were under no

such selective breeding pressures. To enter our homes, they

had only to evolve a people-friendly

disposition.

So are today’s cats truly domesticated? Well, yes—but

perhaps only just. Although they satisfy the

criterion of tolerating people, most domestic cats are feral

and do not rely on people to feed them or

to find them mates. And whereas other domesticates, like

dogs, look quite distinct from their wild

ancestors, the average domestic cat largely retains the wild

body plan. It does exhibit a few morphological differences, however—namely,

slightly shorter legs, a smaller brain and, as Charl les

Darwin noted, a longer intestine, which may have been an

adaptation to scavenging kitchen scraps.

The house cat has not stopped evolving, though—far from it.

Armed with artificial insemination and

in vitro fertilization technology, cat breeders today are

pushing domestic cat genetics into uncharted

territory: they are hybridizing house cats with other felid

species to create exotic new breeds. The

Bengal and the Caracat, for example, resulted from crossing

the house cat with the Asian leopard cat

and the caracal, respectively. The domestic cat may thus be

on the verge of an unprecedented and

radical evolution into a multispecies composite whose future

can only be imagined.

The Truth about Cats and Dogs

Unlike dogs, which exhibit a huge range of sizes, shapes and

temperaments, house cats are relatively

homogeneous, differing mostly in the characteristics of

their coats. The reason for the relative lack of

variability in cats is simple: humans have long bred dogs to

assist with particular tasks, such as

hunting or sled pulling, but cats, which lack any inclination

for performing most tasks that would be

useful to humans, experienced no such selective breeding

pressures.

Note: This article was originally published with the title,

"The Taming of the Cat".

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Carlos A. Driscoll is a member of the University of Oxford's

Wildlife Conservation Research Unit and the Laboratory of

Genomic Diversity at the National Cancer Institute (NCI). In

2007 he published the first DNA-based family tree of Felis

silvestris, the species to which the domestic cat belongs.

Juliet Clutton-Brock, founder of the International Council for

Archaeozoology, is a pioneer in the study of domestication

and early agriculture. Andrew C. Kitchener is principal curator of

mammals and birds at National Museums Scotland, where he

studies geographical variation and hybridization in mammals

and birds. Stephen J. O'Brien is chief of the NCI's

Laboratory of Genomic Diversity. He has studied the genetics of cheetahs,

lions, orangutans, pandas, humpback whales and HIV. This is

his fifth article for Scientific American.

----------------

The Natural History of the Cat

Origins of the Domestic Cat

Cats began their unique relationship with humans 10,000 to

12,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, the geographic region where some of

the earliest developments in human civilization occurred (encompassing modern

day parts of West Asia). One such development was agriculture. As people

abandoned their nomadic lifestyle and settled permanently to farm the land,

stored grain attracted rodents. Taking advantage of this new, abundant food

source, Middle Eastern wildcats, or felix

silvestris lybica, preyed on the rodents and decided to stick

around these early towns, scavenging the garbage that all human societies

inevitably produce—just as feral cats do today.

Over thousands of years, a new species of cat eventually evolved

that naturally made its home around people: felis

catus. Today, pet, stray, and feral cats belong to this species

that we call the domestic cat.1

Cats Travel the World

Cats formed a mutually beneficial relationship with people, and

some scientists argue that cats domesticated themselves.2 Especially

prized as mousers on ships, cats traveled with people around the globe:

- A burial site in

Cyprus provides the first archaeological evidence of humans and cats

living side-by-side, as far back as 9500 BC. Cats must have been brought

to the island intentionally by humans.3

- In ancient

Egypt, cats were worshipped, mummified, and—artwork suggests—kept on

leashes as part of the cult of the goddess Bastet.

- In 31 BC, Egypt

became a province of the Roman Empire. Cats were introduced into Roman

life, becoming truly widespread in Europe around the 4th century AD.4

A cat skeleton from this period shows the shortened skull of domestic cats

today.5

- From Europe,

cats boarded ships to the Americas, reportedly tagging along with

Christopher Columbus, with the settlers at Jamestown, and aboard the Mayflower.

- In Europe, Sir

Isaac Newton is rumored to have invented the cat door in the late 17th or

early 18th century.

- Cats continued

their service as mousers throughout history, even serving as official

employees of the United States Postal Service as late as 19th and early

20th century America.6

- Towards the end

of the 19th century, more Americans began to keep cats for their company

as well as their utility. The first cat show was held at Madison Square

Garden in 1895. By the end of World War I, cats were commonly accepted as

house pets in the U.S.

Throughout all this time, cats were allowed to come and go

freely from human households—even President Calvin Coolidge’s cat had free rein

to wander to and from the White House during the 1920s. As Sam Stall, author of

100 Cats Who Changed Civilization

and The Cat Owner’s Manual,

writes, “Back in Coolidge’s day no one thought of confining cats indoors—not

even one belonging to the president of the United States.”7

Catering to Cats: Inventing

the Indoor Cat

Keeping cats indoors all the time was not possible—nor was it

even a goal—until several important 20th century innovations: refrigeration,

kitty litter, and the prevalence of spaying and neutering.

Even though these changes to our modern lifestyle make keeping

cats inside possible, biologically, cats are the same as they were thousands of

years ago. Their role in our society has evolved and broadened over the last

hundred years, but their basic behaviors and needs haven’t changed.

Cat Food

Unlike dogs, who have undergone many physical changes since

domestication and evolved to survive on an omnivorous diet, cats haven’t

changed much, and still require a high-protein diet. Before the development of

refrigeration and canned cat food in the 20th century, feeding indoor cats who

could not supplement their diets by hunting would have been impossible for most

Americans, who could not afford extra fresh meat or fish.8

Kitty Litter

Up until the 1950s, cats roamed American neighborhoods freely,

using the great outdoors as their litter area. Pans filled with dirt or

newspaper were used indoors by a few cat owners, but it wasn’t until the first

clay litter was accidentally discovered in 1947 and the subsequent marketing of

the Tidy Cats® brand in the 1960s that litter boxes really caught on. With the

invention of cat litter, cats rocketed to popularity as indoor pets, but their

outdoor survival skills remain.9

Spaying and Neutering

Until spaying and neutering pets became available and accessible

around the 1930s, keeping intact cats indoors was messy business during mating

season. Techniques had been developed for sterilizing livestock, but American

households would have had a hard time finding a veterinarian trained to safely

neuter pets before this time.10 Just as cats found their own food

and litter areas outdoors, 20th century cats bred and gave birth outdoors as

they have done since their origins in the Fertile Crescent 10,000 years ago.

While some of those cats’ offspring have since been brought indoors through

neutering and other modern developments, many cats stayed outside, living the

same outdoor lives they always have, with or without human contact. Although

adult feral cats—cats that are not socialized to people—cannot become indoor

pets, neutering and returning them to their outdoor home improves their lives.

Cats are Part of Our

Environment

In the thousands of years that cats have lived alongside people,

indoor-only cats have only become common in the last 50 or 60 years—a

negligible amount of time on an evolutionary scale.

Throughout human history, cats have always lived and thrived

outside. It is only recently that we have begun to introduce reproduction

control like spaying and neutering to bring them indoors. And also, bring the

outdoors to them: using canned food and litter boxes to satisfy biological

needs developed over thousands of years of living outdoors.

Although human civilization and domestic cats co-evolved side by

side, the feral cat population was not created by humans. Cats have lived

outdoors for a long time—they are not new to the environment and they didn’t

simply originate from lost pets or negligent pet owners. Instead, they have a

place in the natural landscape.

[1] Driscoll, Carlos A. et al. “The Taming of the Cat.” Scientific American

(2009): 71-72.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Donalson, Malcolm Drew. The Domestic Cat in Roman Civilization. The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, New York: 1999.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Weir, Harrison. Our Cats and All About Them. Fanciers’ Gazette, London: 1892.

[7] Stall, Sam. 100 Cats Who Changed Civilization. Quirk Books, Philadelphia: 2007.

[8] Bradshaw, John W.S., The Evolutionary Basis for the Feeding Behavior of Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris) and Cats (Felis catus), 136(7) J Nutrition (2006).

[9] Rainbolt, Dusty. “The Best Idea,” Cat Fancy. (August 2010): 30-31.

[10] Grier, Katherine C. Pets in America: A History. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill: 2006.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Donalson, Malcolm Drew. The Domestic Cat in Roman Civilization. The Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston, New York: 1999.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Weir, Harrison. Our Cats and All About Them. Fanciers’ Gazette, London: 1892.

[7] Stall, Sam. 100 Cats Who Changed Civilization. Quirk Books, Philadelphia: 2007.

[8] Bradshaw, John W.S., The Evolutionary Basis for the Feeding Behavior of Domestic Dogs (Canis familiaris) and Cats (Felis catus), 136(7) J Nutrition (2006).

[9] Rainbolt, Dusty. “The Best Idea,” Cat Fancy. (August 2010): 30-31.

[10] Grier, Katherine C. Pets in America: A History. University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill: 2006.

-------------------

dilliaisrael.blogspot.com/2010_05_01_archive.html Cached

May 26, 2010 · Begins with the covenant between God and

Abraham around 1812 BC (over 3,800 years ago) ... Judaism originated

in Israel around 4.000,00 years ago. Founder

-------------------

House Cat Origin Traced to Middle Eastern

Wildcat Ancestor

Brian Handwerk

for National Geographic News

for National Geographic News

June 28, 2007

Cat fanciers

have long known that their feline friends have wild origins.

Now

scientists have identified the house cat's

maternal ancestors and traced them back to the Fertile Crescent.

The Near

Eastern wildcat still roams the deserts of Israel, Saudi Arabia, and other

Middle Eastern countries. (See map.)

Between 70,000 and 100,000 years ago the animal gave rise to the genetic

lineage that eventually produced all domesticated cats.

"It's

plausible that the ancient [domestic cat] lineages were present in the wildcat

populations back as far as 70,000 or 100,000 years ago," said study

co-author Stephen O'Brien of the National Cancer Institute in Frederick,

Maryland.

The

wildcats may have been captured around 10,000 or 12,000 years ago when humans

were settling down to farming, he added.

"One

of nearly 40 wild cat species existing at that time, the little wildcat that

lived in the Middle East had a genetic variance that allowed it to sort of try

an experiment—let's walk in and see if we can get along with those

people," O'Brien said.

One Hell

of an Experiment

A

research team led by geneticist Carlos Driscoll of the National Cancer

Institute and scientists at the University of Oxford in England found five

matriarchal lineages to which modern domestic cats belong.

"This

tells us that domestic cats were sort of widely recruited, probably over time

and space," Driscoll said.

But

people probably weren't going out and catching—or herding—cats.

"The

cats just sort of domesticated themselves. People today know that you can't

keep a cat inside [without barriers], and 10,000 years ago in the Fertile

Crescent you couldn't just shut the window."

Farmers

were likely the first to domesticate wildcats. The animals may have been

helpful in hunting mice and other pests that plagued farm fields in the early

human settlements, which had just sprang from the first agricultural

development.

Agriculture led to cities and towns, as well as a

new ecological environment that cats were able to exploit.

There are some 600

million house cats around the world, study co-author O'Brien added.

"Domestication

was one hell of a successful natural experiment."

Cats on the Move

Once the formerly

wild felines became household companions, the same cats appear to have

accompanied human tribes as they gradually migrated and spread throughout the

ancient world. (Check out our

ancestors' journey through the Fertile Crescent.)

"It's sort of

analogous to the 'out of Africa' theory that people talk about for

humans," Driscoll said. "In the same way, domestic cats from Europe

are really the same as domestic cats from Israel or China or wherever."

The earliest

archaeological evidence for domestic cats has been found in Cyprus and dates

back approximately 9,500 years.

(Read: "Oldest

Known Pet Cat? 9,500-Year-Old Burial Found on Cyprus" [April 8,

2004].)

Cat studies of all

types are hindered by the many physical and behavioral similarities between

domestic cats and their wild relatives. In fact, it is often difficult or

impossible for even the trained eye to tell them apart, and interbreeding has

created many hybrids of the two.

Genetic Clues

Driscoll's study

began because genetics may be one of the only ways to determine which cats are

truly wild. His group managed to successfully herd about a thousand wild and

domestic cats and sample their DNA to produce the genetic study, which will

appear in tomorrow's issue of the journal Science.

In search of cats'

wild ancestor, the team studied modern wildcat subspecies including the Near

Eastern wildcat, the European wildcat, the Central Asian wildcat, the southern

African wildcat, and the Chinese desert cat.

The sampling of

feline genes revealed that the Near Eastern wildcat and domestic cats fell into

the same genetic clade, a group of species with the same ancestor. This meant

the ancient ancestors of the wildcats were likely the first cats to be

domesticated.

The genetic diversity

of living cats revealed that they must have existed for some 70,000 to 100,000

years to produce that degree of diversity.

--------------------

Jewish Foods:

Dining in the Holy Land - 2000 Years Ago

Dining in the Holy Land - 2000 Years Ago

by Daniel Rogov

Jewish Foods: Table of Contents | Holiday Foods | Israeli Foods

Regardless of whether the

cultural and religious lives of people are governed by the Hebrew, Islamic,

Greek, Russian or Armenian Orthodox, Buddhist or Vietnamese calendars,

many public events the world over are determined by the Gregorian Calendar. As

is well known, in accordance with that calendar, the new year starts on January

1st, and is celebrated primarily on the night of December 31st. The

celebrations for this year were special, for in addition to marking the end of

a century, we celebrated the beginning of a new millennium. What is not so well

known about the celebrations that mark the end of a year (or a millennium), is

that this phenomenon has long been a sore point among the members of the clergy

of nearly all the faiths, who all agree that the roots of New Year's Eve

celebrations are distinctly pagan in nature.

As long ago as 500 BCE,

Romans believed that loudness, lewdness and at least a modicum of drunkenness

were necessary to celebrate the onset of the new year. It was thought that such

behavior would confuse Pan and the other malicious gods, thus preventing them

from interfering in the everyday lives of mortals for the year to come. Half a

millennium later, the Goths adopted a similar belief, thinking that such

behavior on the eve of the new year was a sure way to frighten away any evil

demons that might be left over from the year that had passed.

January 1st has not always marked

the onset of the year. Because the ancient Romans

began their year in March (more for the convenience of the tax collectors than

out of respect to the motion of the planets), such words as September, October,

November and December, meaning the 7th, 8th, 9th and 10th months, had a

rational meaning. In fact, only since the reform of the calendar in the 16th

century, has January 1st been accepted as New Year's Day.

Nor has the onset of the new year

always implied celebrations, promises and hopes for the future. Since the time

of the ancient Greeks,

the first day of the year has been considered by many to be the most

appropriate day of the year for bribing local officials. Even today in some

parts of the world, it is considered appropriate for wealthy citizens (or their

servants), owners of small businesses and other local entrepreneurs to call on

local officials to pay their respects and to share a cup of coffee or tea as a

token of goodwill. In France,

perhaps as an offshoot of this tradition, adults enjoy exchanging gifts on

January 1st.

There are other names given to

the last night of the year, the origins of which are unclear. Even though

Europeans (and some Israelis and North Americans in recent years) have come to

know the night of December 31st as 'Sylvester', this appelation is relatively

new, having its roots in 18th century France. Whether the Sylvester in question

is an otherwise obscure French saint, the Roman-Catholic pope who is said to

have brought a dead bull back to life or the maiden name of the mother of Dom

Perignon, the man who discovered the process of making sparkling Champagne, is

not known.

Whatever, the third millennium

has arrived and from the culinary point of view, it is interesting to look back

and examine the dining habits of people in the Holy Land 2,000 years ago.

Before we begin our voyage, keep in mind that the people who lived in

Jerusalem, Jericho and other places in the Holy Land two millennia ago dined

quite well. In addition to having excellent markets filled with fresh

vegetables, fruit, poultry, lamb and fish, the narrow streets of the ancient

cities were lined with numerous stalls where vendors sold fried fish, pickled

cucumbers and freshly grilled meats. Moreover, the roads from Jerusalem

to Jericho

and from Hebron

to Jaffa

were lined with stands where grilled lamb, pickled watermelon rind and cakes

made from chickpeas were readily available. Whether for at-home dining or while

travelling on the road, hungry men and women had no problem finding good things

to eat. What may surprise us is that many of the dishes prepared then are

marvelously appropriate even today, especially for celebrating the end of one

millennium and the beginning of another.

The Best Known of

All Meals

In addition to having been

recorded in the New

Testament by Saints Mark and Matthew, "The Last Supper," the last

meal shared by Jesus

and the twelve disciples, has also been immortalized by dozens of well known

artists. The best known representation of that meal is probably the fresco

painted by Leonardo da Vinci between 1495 - 1498 on the wall of the Monastery

of Santa Maria delle Grazie in Milan.

Da Vinci was not the only artist

who tried to capture the mood and meaning of this meal. In addition to

frescoes, paintings and etchings by Raphael, Titian, Correggio, Tintoretto,

Rembrandt and Salvadore Dali, the last public meal of Jesus has also been

portrayed in hundreds of 5th and 6th century Byzantine mosaics, in a 13th

century bas relief on the eastern transept of the Cathedral in Strasbourg, and

in a 15th century bronze relief by Donatello, found in the church of San

Giovanni in Siena.

Even though Jesus' last supper is

one of the most frequently portrayed religious events in history, no one is absolutely

sure what was eaten at that meal. Although it is impossible to know precisely

what dishes were served, both the New Testament and historical records give us

many clues. According to the New Testament (Matthew

26 and Mark

14), the meal was intended to celebrate Passover,

and both accounts agree that two of Jesus' disciples had come to Jerusalem

in order to find a home in which Jesus could enjoy the Seder. The year was

probably 33 CE,

and even then the holiday was a commemoration of the Hebrews' freedom from

slavery in ancient Egypt nearly two thousand years before Jesus was born.

There is no reason to believe that

the meal upon which Jesus dined would have been different than that enjoyed by

other Jews at the onset of this first millennium. Thus, matzot (unleavened

bread), a pitcher of wine, salted water and a small bowl of marror (bitter

herbs) would have been on the table. Because in Jesus' time the holiday also

marked the time of the early spring harvest, the table may have been decorated

with fresh fruit, green almonds and walnuts as well as sprigs of freshly picked

herbs such as thyme, rosemary and coriander.

As was the case in nearly all

Jewish homes of that time, when Jesus and his disciples sat down, they would

have found the table already set with all the foods of the meal. In addition to

the serving plates that held the food and the goblets for the wine, little else

would have been on the table. Napkins were not yet in use and the fork had not

yet been invented. Each guest would have brought his own knife for cutting

meat, but most of the eating would have been done by hand. Because this made

for sticky fingers, servants were available to offer bowls of water in which

the guests could occasionally clean their fingers.

Between the 1st and 3rd

centuries, it was traditional in all homes to start with a simple vegetable

soup. The contents of the second course, however, were determined largely by

the economic status of the host. Because Jesus was an honored guest, the owner

of the home in which this particular meal was served would have been sure to

have prepared roast lamb, the most highly-valued of dishes. It was not

traditional to serve a dessert course, but celebratory meals such as this came

to an end after the guests ate the fresh fruit and nuts that had been put on

the table for decorations.

Apples and Excesses

The Romans

who occupied the Holy Land at the onset of the first millennium were not quite

as moderate or decorous in their personal behavior or dining habits as was the

native population. It is well known, for example, that in 40 BCE, when Herod

fled from Jerusalem

to escape from Antigonus II (Mattathias) who had been made king by the

Parthians, he went to the high hill of Masada.

What is not so broadly known is that Herod

made his safe home into one of the most luxurious palaces ever constructed in

the Middle East.

After making the move from Jerusalem

and installing his family in rough quarters on Masada,

Herod

visited Rome.

Upon his return, according to the Jewish historian Josephus,

"he built there a fortress as a refuge, suspecting a twofold danger: peril

on the one hand from the Jews lest they should depose him and restore their

former dynasty to power; and the even more serious threat posed by Cleopatra,

Queen of Egypt." Between 37 and 31 BCE, Herod

transformed the rock of Masada

into a mighty fortress. What Josephus

fails to mention is that Herod

also transformed it into a palace where pleasures of every sort might be freely

pursued.

It must be understood that the

pleasures of wealthy Romans involved three things: food, wine and sexual

promiscuity. Thus, following precedents established by Lucullus and Alexander

the Great, both of whom were well known gastronomes, Masada

became renowned for its ten-hour banquets - orgiastic feasts - where a party

might begin with hors d'oeuvres of chickens, ducks, geese, hares, pigeons,

turtledoves, partridges and young goats. This was followed traditionally with

entertainment provided by naked girl dancers, and then by a second course of pigs

stuffed with thrushes, ducks, warblers, pea puree, oysters and scallops, all

consumed to the accompaniment of troupes of acrobats tumbling among swords,

breathing fire from their mouths and acting out obscene parodies. Later courses

included roast boars and oxen and then, when the eating tapered off, the

drinking began in earnest and the dancing girls did far more than dance.

"Apples and fornication," wrote one of Herod's guests, "were the

most popular of last courses."

Based on traditions adopted from

the Greeks,

such feasts were traditionally divided into two parts: the first, in which one

primarily ate; and the second, the symposium, in which one primarily drank,

talked or otherwise amused oneself. Modern-day professors and students will be

pleased to know that the original symposium (from the Greek for "drinking

party") began in earnest at the end of the eating. When this habit was

first adopted, Xenophon wrote that "drink, discussion, games and

fornication were equal parts of the well-conducted symposium." Atheneus

speculated that the best symposia would be identified as those where most of

the guests "fell into a sexually-induced drunken sleep before the evening

had ended."

The main meal at Masada

took place, as it did in Rome,

during the mid- or late-afternoon, the guests reclining on couches placed about

the table. These couches had an incline at one end so that the heads of the

diners rose above the level of the board or table. Diners rested on their left

arms and reached for food with the right. Couches were generally grouped about

three sides of the table, leaving the fourth side open for service and

entertainers, and the place of honor was the right-hand couch opposite the

empty side of the table.

One may have noted that to this

point there has been no mention of the presence of women at the dining table.

This is because Roman men had determined that feasting was an activity too

important to be shared with women. When they finally decided to allow women to

join them, it was not so much out of a sense of fairness but because they

thought that female companionship would be good for the digestion.

As Roman decadence soared, tastes

became more jaded and the symposia deteriorated into little more than orgies.

Despite this, some of the dishes enjoyed by the Romans were actually quite

delicate and have maintained their popularity to this day. The following recipe

is a sample of a popular Roman dish known to have been served at Masada.

More Cultured Roman

Influences

At the onset of the first

millennium, the poor folk of the cities and the peasants in the countryside

dined pretty similarly to all Mediterranean peoples of that time - their diet

heavily made up of bread, rice, barley, lentils, chickpeas, eggplant,

artichokes, onions, garlic, olive oil, yoghurt and, when they could afford it,

the meat of lambs and goats. The middle-classes and the rich, however, often

tried to emulate the dining habits of the Romans, and one of the heroes of the

land was the Roman epicurean named Apicius.

Actually there were three great

Roman epicureans with that name and, despite popular folklore, all were more

famous for their gluttony than their good taste or culinary achievements. The

first Apicius lived during the reign of Sulla, the second under Augustus and

Tiberius and the third under Trajan. The Apicius that attained the greatest

fame was the second, Gavius Apicius, who spent enormous sums on dining and

entertaining and who invented many new dishes. It is possible that it was also

this Apicius who founded the "school for good fare" referred to by

the dramatist-philosopher Seneca.

In addition to being a well-known

public figure, Apicius was also inordinately fond of high living. Possibly

because his penchant for entertaining lavishly dominated his life, he built up

a mountain of debts. When he found himself left with an annual income of only

250,000 sesterces (about $200,000 today), he felt he could no longer live in

the style to which he had become accustomed and committed suicide by poisoning

himself.

It was also this Apicius who

wrote De re Culinaria, the oldest cookbook still in existence. Most

culinary experts today agree that Roman cooking, whether in Rome or in

the Holy Land, was sumptous and magnificent, but fundamentally barbarious.

Because they relied heavily on vinegar (to hide the smell of spoiled meat), and

heavy, greasy sauces, very few of the dishes so beloved by Apicius' compatriots

would be considered tasty today. Despite this failing, many modern chefs have

named inventions after Apicius, not so much to honor his gastronomic knowledge

as his extravagant lifestyle.

And Now - Israel

Going into the Third Millennium

Although the culinary influences

of ancient Rome and Greece no longer play a major role in the daily dining

habits of most of the residents of Israel, it is not at all difficult to plan a

meal that will be ideal for celebrating the onset of the new millennium.

Following are three recipes for such a meal, one each from a Jewish, Muslim

and Christian source, all completely modern, all delicious and all highly

valued wherever one finds oneself in Israel. The recipes are designed to serve

4 - 6.

-------------------

Dogs

Use Subway, Cat Takes Bus and Other Adventures in Animal Intelligence

Jan 7, 2012 5:00pm

(ABC)

3 Videos Underline New Questions About What ‘Wild’ and ‘Tame’ Really Mean

Nature’s Edge Notebook #12 –

Observation, Analysis, Reflection, New Questions

Stray

dogs figure out how to use Moscow’s subway system to get downtown to

neighborhoods where the food is better.

For

years, a house cat in England takes the public bus to get around town,

unbeknownst to its owner.

A

jungle leopard in India, needing to cross a swollen river with its cub, gets a

man to ferry her and her cub across in his canoe.

Dolphins

at a dolphin show in Hawaii instantly figure out a mistake their trainers have

made and cover for them pretty well, preventing embarrassment all around.

The

wild ocean cousins of those “tame” show dolphins have a long-standing

partnership with fishermen along the coasts of both Brazil and Bengal that

means more fish for all.

In

Western Australia’s Shark Bay, wild dolphins being studied by scientists from

Harvard, appear themselves to be studying the humans — including this reporter.

These

anecdotes may at first seem to be simply entertaining aberrations — fun animal

stories of unusually “tame” — and surprisingly intelligent — animals.

But

scientists are now collating and comparing so many of these stories — literally

thousands from around the world, often from what we’ve traditionally called

“the wild” — that it’s all raising new questions about what the words

“tame” and “wild” may really mean, and how any difference between the two

can be usefully described.

These

anecdotes are also at the heart of an explosion in the study of animal

intelligence and consciousness, a scientific revolution that promises to help

answer ancient questions that still persist about the nature of our own human

intelligence and consciousness.

They

include stories from around the planet in which all sorts of wild species

accommodate to the many disruptions of encroaching humanity with imaginative

flexibility and self-aware decision making that leave scientists searching for

explanations.

Of

course, the wild animals have little choice but to accommodate us, since if

they are to live, they must continue to seek food each in their own way,

regardless of any human presence.

But

these myriad encounters are also revealing unsuspected powers of perception and

adaptation — and emotional intelligence — in all sorts of fur-covered brains

and deep-diving bodies.

They

are transforming notions not only of a presumed superiority of human

intelligence, but of the uniqueness (now increasingly in doubt among some

experts) of human consciousness.

If

wild animals seem to intelligently allow themselves to become more “tame” in

our presence so that they can go on surviving, does that make them any less

“wild”?

“Not

tamed, but habituated,” is how the guide in our recent hunting foray in Botswana with Africa’s

endangered Wild Dog put it.

He

not only took us on a truly wild chase, careening through the bush with

the wild dogs (a.k.a. the painted wolf), that ended with the capture and

devouring of a hapless baby impala (which meant wild dog pups could be fed),

but along the way we also captured many glimpses of animals — including hippos,

lions, jackals and hyenas — pursuing their “wild” behavior in their ancient

homeland even while in close proximity with and accommodation to our

human-filled open Land Rovers.

Three

“Nature’s Edge” video segments below, starting with the Moscow stray dogs

who’ve mastered the subway system, show some of these remarkable examples of

animal thinking and accommodation that are now so engaging scientists.

We

are guided through them by “Nature’s Edge” regular Eugene Linden who’s been

writing about animal intelligence studies worldwide for more than 40 years.

They

are part of our ongoing series “Thinking About Thinking With Eugene and Other

Animals” (a title that honors the slim and timeless classic, “My Family and

Other Animals” by Gerald Durrell — a childhood memoir of great seriousness and

comic genius).

“The

world is becoming a zoo,” says Linden — speaking from the human point of view.

We

have penetrated so many wild places, that animals have less and less option but

to roam and hunt in among us.

But

from the animals’ point of view, we’re the wild ones, so to speak, among whom

they must now try to keep their own, often genetically determined,

“civilizations” intact, their ancient evolved patterns of life and survival.

And

scientists are now discovering the remarkable (to us) intelligence and apparent

consciousness with which wild animals are doing that.

Linden

says these discoveries involve overcoming natural human prejudices: “Since we

usually define intelligence in our own terms, humans will tend to assert our

intelligence’s superiority over any other species, even if we can’t agree on

what it actually is.”

The

three videos below culminate with an influential insight about animal

intelligence and consciousness from the late ethologist Donald

Griffin.

Griffin

led scientists to admit that far from being the dumb creatures many thought in

the 19th century, incapable even of pain, animals, even very

simple ones, may have developed “consciousness” in some form or other from the

start because it is simply the easiest — most efficient — way for evolution, in

the form of Darwinian natural selection, to advance.

But

first, meet some stray dogs who have mastered the Moscow subway system — as

well as Eugene Linden, and that English cat riding the bus.

Sometimes

editors know they may have a real story when after hearing rumors of it and

then assigning it, the correspondent reports back that it was not hard to find.

That’s

what ABC News correspondent Alex Marquardt told us over the phone a few days

after we told him of reports we’d seen here in New York that some of Moscow’s

stray dogs had figured out how to use the subway to get from the roomier

suburbs where they lived to the heart of the city, where they had a better

chance of turning humans into a food source — just like the millions of human commuters

who use subways every day to get from their homes to where they work.

Alex

told us that after speaking to the two Russian biologists who’d been studying

these dogs, he linked up with his cameraman and joined the midtown Moscow

commuters heading down into subways to see if it was really true.

Sure

enough, before long, not hard to find at all, there she was…

Take

a look:

In this next video segment, we learn that during his 40 years

traveling the world to talk to animal trainers of all kinds and to scientists

who try to figure out how to describe animal thinking, Eugene Linden began to

see the biases humans have often had about animal thought.

Until

recently, he says, many scientists thought of animals as “failed humans.” Some

even argued that animals couldn’t really feel pain.

After

telling us of a famous New York City “tame” zoo otter who found ways to extort

rewards from others — presumably a tactic otters can also use in “the wild” if

they want — Linden spoke of the engaging behavior of a leopard in the Indian

jungle who needed a favor from a man who lived not far from her den.

When

the nearby river flooded, this leopard, seeking to get her cub across to

shelter, led the man to his canoe, stepped into it, looked over her shoulder at

him, and somehow conveyed what needed to happen next — as this video shows.

And

on a foray into what this reporter now thinks of as, in a sense, the civilized

world of the so-called “wild” dolphin (civilized by dolphin standards), when we

took a crew to Western Australia’s Shark Bay, we became aware of our own biases

about who was studying whom.

In this third video segment, we hear how, in an act of remarkable

resourcefulness and possibly even empathy, two dolphins in Hawaii helped their

trainer, the scientist Karen Pryor, save face.

This

is just another of the thousands of anecdotes now being compared and studied

that are giving scientists around the world second thoughts about the nature of

animal intelligence and the uniqueness (or not) of human consciousness,

whatever that may be.

The

nature of consciousness is still hotly debated among scientists, philosophers

and psychologists.

The

late scientist Donald Griffin advanced this debate. He broke through

scientific presumptions and confusion with a deceptively simple insight about

why Darwinian evolution would select for consciousness in all sorts of animals.

Not

that this insight is suggesting there are “termites doing crossword

puzzles,” as Eugene Linden says here (and why would they want to?) but it does

seem to make the mystery of awareness and consciousness all the more

common — although no less mysterious.

Linden

— and Griffin — point out that for evolution to try to “hardwire” a

species for every dangerous or life-giving eventuality that might come down the

pike in this often wild and chaotic world would be cumbersome, if not

impossible. Who knows what new developments the future may hold?

These

new insights may give new hope about the flexibility with which even humans

might adjust to meet new dangers and opportunities.

If

other species turn out to have minds that are not so “hardwired” and that

display imaginative, compassionate, self-aware and flexible decision making,

then, some scientists now suggest, (turning the tables of interspecies

prejudice with a little wry irony) we humans may also share such splendid

capacities — at least in our better moments.

Video: Watch giant cuddly cat help commuter travel to work in bizarre

Japanese chewing gum advert

·

By Ben Burrows