SPIRITUALITY, RELIGION, CULTURE, AND PEACE:

EXPLORING THE FOUNDATIONS FOR INNER-OUTER PEACE

IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

Linda Groff

California State University

Paul Smoker

Antioch College

"If a man sings of God and hears of Him, And lets love of God sprout within him, All his sorrows shall vanish, And in his mind, God will bestow abiding peace." --Sikhism

"A Muslim is one who surrenders to the will of Allah and is an establisher of peace (while Islam means establishment of peace, Muslim means one who establishes peace through his actions and conduct)."--Islam

"The Lord lives in the heart of every creature. He turns them round and round upon the wheel of Maya. Take refuge utterly in Him. By his grace you will find supreme peace, and the state which is beyond all change." --Hinduism

"The whole of the Torah is for the purpose of promoting peace." --Judaism

"All things exist for world peace." --Perfect Liberty Kyodan "Blessed are the peacemakers for they shall be called sons of God." --Christianity

"Peace ... comes within the souls of men when they realize their relationship, their openness, with the universe and all its powers and when they realize that at the center of the universe dwells Wakan-Tanka, and that this center is really everywhere, it is within each of us."--From The Sacred Pipe, by Black Elk, Lakota Sioux Medicine Man

Introduction

This paper is about different spiritual and religious traditions in the world and how they have or could in the future contribute to the creation of a global culture of peace. As the above quotations indicate, almost all of the world's religions, in their own sacred writings and scriptures, say that they support "peace". Yet it is a known fact that war and violence have often been undertaken historically, as well as at present, in the name of religion (as is discussed further below). Yet religions profess to want peace. So what is 'peace'? And how have religions historically helped to promote peace, and how might they help create a more peaceful world in the 21st century? These are a few of the questions that this paper will attempt to explore.Traditionally many people focus on how wars and conflicts are seemingly undertaken for religious reasons, or at least undertaken in the name of religion. Indeed, it is not difficult to find data and statistics in support of this hypothesis. Quincy Wright, in his monumental study, A Study of War , documents numerous wars and armed conflicts that involve a direct or indirect religious component, (Wright, 1941) as does Lewis Richardson in his statistical treatise, Statistics of Deadly Quarrels. (Richardson, 1960)

As the Cold War has ended and inter-ethnic conflicts have re-emerged in many parts of the world, it has indeed been a popular thesis of different writers to argue that these inter-ethnic conflicts often have a religious component. A few examples of such recent writing include: Samuel Huntington's, "The Clash of Civilizations," Foreign Affairs (Summer 1993); Daniel Patrick Moynihan's Pandaemonium: Ethnicity in International Politics; and R. Scott Appleby, Religious Fundamentalisms and Global Conflict.

Following UNESCO's lead in holding two conferences on "The Contributions of Religions to a Culture of Peace" (both held in Barcelona, Spain, in April 1993 and December 1994), and other interfaith dialogues between different religions that are occurring in a serious way around the planet--including the World Parliament of Religions, in Chicago, August 1993; 1and the ongoing work of the World Council on Religion and Peace--this paper will focus instead on how religious and spiritual traditions can contribute to creating a more peaceful world via an exploration of the foundations for both inner and outer peace in the twenty first-century. The paper will have four parts:

I. Exoteric/Outer and Esoteric/Inner Aspects of Religions

Part I begins by providing a framework for looking at all the world's religions as having a potential spectrum of perspectives, including: the external, socially-learned, cultural or exoteric part --including different religious organizations, rituals, and beliefs, which are passed down from one generation to the next, and the internal, mystical, direct spiritual experience or esoteric part. In considering the external aspects of religion, principles from the field of intercultural communication are used to explore the creation of tolerance, understanding and valuing of diversity concerning different aspects of socially learned behavior or culture, including religion.Fundamentalism or religious extremism or fanaticism--when religions claim their version of religion is the only one--are seen as an extreme form of the socially-learned aspect of religion and one not conducive to creating world peace. In considering the internal or esoteric aspects of religion, it is noted that all the world's religions began with someone who had a mystical enlightenment or revelatory experience, which they then tried to share with others, leading often to the formation of new religions--even though this was not the intention of the original founder. Parallels between new scientific paradigms and ancient mystical traditions from the world's religions are then noted to illustrate how contemporary dynamic, interconnected, whole systems ways of experiencing and viewing reality can be seen as providing necessary conditions "within the individual" for creating an external global culture of peace in the world.

II. Further Explorations of the Esoteric/Inner

and Exoteric/Outer Aspects

of Religion and Culture

Part II continues the exploration of the inner and outer aspects of religion

and culture. Here, three different topical areas are explored: first, the work

of Pitirim Sorokin on the alternation historically within Western cultures between

ideational/spiritual/inner values and sensate/materialistic/outer values; second,

the evolution or change historically from female to mixed to male aspects of

divinity within different religions and cultures, as this relates to changing

values and worldviews; and third, the work of Joseph Campbell and the universal

theme of "the hero's journey" (or search for inner meaning) in the

myths of all cultures--even though the outer form of the journey can vary from

one culture to the next.

III. Inner and Outer Aspects of Peace, the Cultures

of Peace, & Nonviolence

(Paralleling Esoteric & Exoteric Aspects of Religion)

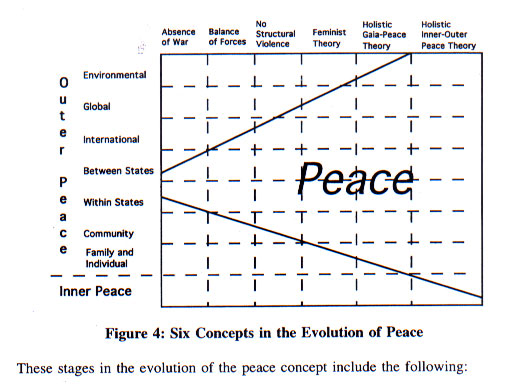

Part III traces the evolution of the concept of "peace" within Western

peace research, including the recent development of more holistic definitions

of peace that are consistent with the ideas explored in Part I of this paper.

The conceptual shift involved in moving from peace as absence of war through

peace as absence of large scale physical and structural violence (negative and

positive peace respectively) to more holistic definitions of peace that apply

across all levels and include both an inner and an outer dimension, represents

a substantial broadening of the peace concept in Western peace research. Part

III then uses the above evolution in the concept of peace as a framework to

explore different dimensions of "a culture of peace," as well as different

dimensions of "nonviolence." Gandhian, spiritually-based nonviolence

is seen as a link between inner and outer forms of peace.

IV. An Agenda for Future Peace Research--Based

on the Need

to Focus on Both Inner and Outer Aspects of Peace

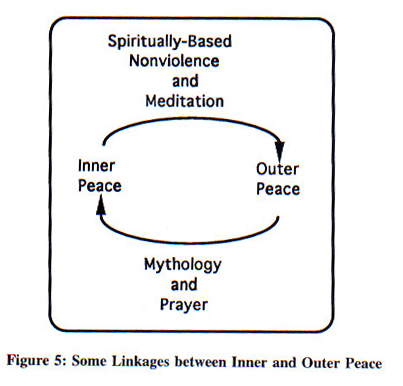

Part IV argues that Western peace research has focused almost entirely on

outer peace, but that in future it needs to deal with both inner and outer aspects

of peace in a more balanced way. In order to do this, it is suggested that peace

research elaborate on the different dimensions and levels of inner peace, just

as it has done for outer peace, and that it expand its methodology to include

other ways of knowing besides social scientific methods only. Finally, peace

research needs to redress the inbalance between negative and positive images

of peace by exploring not only what it wants to eliminate, for example war and

starvation, but also what it wants to create in a positive sense.Please note that this paper is an ongoing project that will become a book. At present, some sections of the paper are developed more than others, but the basic framework is here. Please contact the writers in the future for later elaborations of this writing. We offer this version of the paper with humility, aware that further revisions and elaborations are necessary.

PART I: EXOTERIC/OUTER AND ESOTERIC/INNER ASPECTS OF RELIGIONS

A. MYSTICAL EXPERIENCE, ORGANIZED RELIGION, AND FUNDAMENTALISM: A FRAMEWORK FOR LOOKING AT ALL THE WORLD'S RELIGIONS

Before considering the external and internal aspects of religion, it is important to note that within any religion, there is a potential spectrum of possible perspectives on the teachings of that particular religion or spiritual tradition, including how those teachings relate to world peace. First, there is religion as socially-learned behavior, i.e., as part of culture--what can be called "organized religion." Here religious beliefs, rituals, and institutions are learned and passed down from one generation to the next, and religious institutions are an integral part of the social structure and fabric of culture.When religious beliefs take the form of rigid dogma, and the believers' beliefs and behavior are known to be right, while those of non believers, or other religions--or even different variants within one's own religion--are known to be wrong, this leads into what has been variously called "fundamentalism" or "fanaticism" or "extremism"--a global trend in almost all of the world's religions today.

At the other extreme are mystical traditions which are based on direct inner spiritual experiences. Here, such mystical, revelatory, or enlightenment experiences (rather than socially learned behavior and beliefs) constitute an important part of one's spiritual life. Such spiritual experiences have also occurred in mystics from all the world's religions throughout the ages. Indeed, the founders of the world's religions were themselves usually mystics, i.e., people who had revelatory or enlightenment experiences which they then tried to share, as best they could, with others--even though they were often not trying to establish a new religion at the time (which was often left to their followers to do).Given these considerations, it is possible to look at any religion as having a potential spectrum of different forms within it, each discussed separately in the paper, as follows:

MYSTICAL/SPIRITUAL______ORGANIZED RELIGION______FUNDAMENTAL

TRADITIONS AND BELIEFS OR EXTREMISM

|

||

| (direct inner experience) | (part of social learning and culture) | (my dogma/beliefs are right and yours are wrong; also social learning and culture) |

| Figure 1: Spectrum of Potential Perspectives Within Any Religion | ||

It is interesting that mystics of all religions can usually communicate

with each other and appreciate the spiritual or God force operating within each

other--no matter what religious tradition the other mystics come from. Organized

religion is often tolerant of different religious traditions, as seen in ecumenical

movements around the world, but there can be misunderstanding between religions

based on differing beliefs and practices. These misunderstandings can be lessened

by educational programs focusing on the appreciation and understanding of cultural

and religious diversity. But fundamentalism often stresses how one particular

interpretation--of religion, scripture, and religious practices--is right and

other interpretations are wrong. This difficulty of fundamentalists, from any

religion, in dealing with diversity in a tolerant manner presents a major problem

for peaceful relations and understanding between religions and cultures and

hinders the creation of a global culture of peace.

If the whole world were mystics--who tend to honor the mystical

experience in people from all the world's religions--world peace would be easier

to achieve than it is today. But mystics are a very small percentage of the

world's population and so misunderstandings, conflicts, and wars have often

resulted historically, in part at least, over different religious interpretations

of what constitutes proper beliefs, practices, rituals, and organizational forms,

i.e., over the socially- learned aspects of religion.

B. EXOTERIC/OUTER FORMS OF RELIGION

This section of the paper will look at exoteric or outer forms of religion, i.e., religion as part of our socially-learned behavior or culture--whether it takes the form of traditional organized religion or a more extremist or fundamentalist form, and how principles from intercultural communication and conflict resolution can help people deal constructively with cultural and religious diversity.1. Religion as Socially-Learned Behavior or Part of Culture

"Religion is man's inability to cope with the immensity of God." Arnold ToynbeeOne way of looking at religion is as part of culture through socially learned behavior. "Culture" can be defined as learned, shared, patterned behavior, as reflected in technology and tools; social organizations, including economic, political, religious, media, educational and family organizations; and ideas. In this way, religion is shared by a group of people, learned and passed down from one generation to the next, and is clearly reflected in both religious organizations and beliefs. "Socialization" is the process through which culture is learned, including our religious beliefs and practices. The agents or institutions of socialization include language, (a factor individuals are often least conscious of), politics, economics, religion, education, family, and media.

"Rain falling in different parts of the world flows through thousands of channels to reach the ocean...and so, too, religions and theologies, which all come from man's yearning for meaning, they too, flow in a thousand ways, fertilizing many fields, refreshing tired people, and at last reach the ocean." Sathya Sai Baba

While Anthropologists have often studied one culture, including its institutions, in depth, others have undertaken cross-cultural, comparative studies. More recently the field of intercultural communication has emerged, (Groff, 1992) as witnessed in the emergence of specialist inter-cultural organizations, such as The Society for Intercultural Education, Training, and Research (SIETAR). While cross-cultural studies deal with comparing some aspect of life, such as religious institutions and beliefs, from one culture to another, intercultural communication deals with the dynamic interaction patterns that emerge when peoples from two or more different cultures, including religions, come together to interact, communicate, and dialogue or negotiate with each other. There are general principles of intercultural communication. There are also studies of particular cultures interacting, based on a belief that when persons from any two specific different cultures come together to interact with each other, that they will create their own dynamic interaction process, based on the underlying values of both groups, just as any two individuals will also create their own dynamic interaction process.

A significant problem with organized religion and belief, as this relates to peace and conflict, is individuals and groups often confuse the map (their socially-learned version of reality or culture or religion) with the territory (or ultimate reality), as elaborated below. Thus people believe that their personal or subjective version of reality or religion is valid, while other views are invalid. Instead it can be argued that the many maps are different, but possibly equally valid interpretations and attempts to understand the same underlying reality or territory.

2. Fundamentalism: Taking Organized Religion and Beliefs into Dogma

Fundamentalism seems to be a trend in almost all the world's religions today. The term "fundamentalism" had its origins in "a late 19th and early 20th century transdenominational Protestant movement that opposed the accommodation of Christian doctrine to modern scientific theory and philosophy. With some differences among themselves, Christian fundamentalists insist on belief in the inerrancy of the Bible, the virgin birth and divinity of Jesus Christ, the vicarious and atoning character of his death, his bodily resurrection, and his second coming as the irreducible minimum of authentic Christianity." (Grolier, 1993) More recently the concept has been applied not only to conservative, evangelical Protestants, but also to any Christian group which adopts a literal interpretation of the Bible and to groups from other religious traditions who similarly base their religious views on a particular and exclusive, literal interpretation of their holy book. For example, radical Islamic groups, such as Islamic Jihad, are seen as examples of Islamic fundamentalism, although a different term is preferred. In the Islamic tradition the word fundamentalism, when translated into Arabic, has a completely different and positive meaning. In Arab countries the appropriate word for describing literal religious fanaticism is "extremism." (Al-Dajani, 1993) In this paper the term "fundamentalism" is used in the broad sense to portray any religious group or sect from any religious tradition, which adopts purely literal, as opposed to metaphorical or mythical, interpretations of their holy book, and which denies the validity of other interpretations or religious traditions, believing truth resides with their perspective only.Because fundamentalists in any religion turn the beliefs of their religion into dogma, and also tend to interpret the scriptures of their religion in a literal way only, thus missing the many subtle levels of meaning as well as analogies with teachings from other world religions, they can end up stressing primarily how they are different from other world religions, and even from different interpretations within their own religion, rather than stressing any commonalities they might share with other world religions. This more limited interpretation of their scripture can then lead to dogmatic views that their interpretation of religion, and reality, is correct and everyone else is wrong.

An interesting and important question for peace research and future studies is why there is such an upsurge in fundamentalism in so many of the world's religions in so many different parts of the world today? Of the many possible explanations for this phenomena, two hypotheses will be explored here. The most obvious hypothesis would argue that people are overwhelmed by the increasing pace of change today, and are desperately seeking something that they can believe in as a mooring to help them through all this change in the outer world which is uprooting their lives and creating great insecurities in their lives. In the case of fundamentalism, this can involve returning to some over-idealized vision of their religious roots, which may never have existed in the idealized form that they remember, and trying to literally enforce that interpretation of reality on all the members of their group. In such situations, people may need time to try to go back to a stringently defined earlier way of life and see if they can make it work, and only when they see that the world has changed too much to return to the past will they then be ready to move forward into the future. This hypothesis is consistent with the view that any religious or spiritual tradition needs to be constantly adapted to the world in which it finds itself--if it wishes to remain a living, breathing, spiritual force that people experience in their lives, rather than become an outdated institution based on dogma or rules.

A second related hypothesis, to explain the rise of fundamentalism in the world today, relates to the dual trend towards both globalism, as well as localism. The globalization process of the last 50 years has led to a dramatic increase in global governance structures, including an expansion of the multi- faceted United Nations (UN) system, an increase in scope of regional economic and political organizations, such as the European Community (EC) and the North American Free Trade Area (NAFTA), and the continuing proliferation and development of International Governmental Organizations (IGOs). The growth in IGOs and the increase in size and scope of United Nations activities, such as the expanded scope of United Nations Peace Keeping operations, has had a major impact on international relations.

A similar expansion of activities can be seen in the work of various international scientific, educational and cultural organizations, as indexed by the continued growth in International Non Governmental Organizations (INGOs). Millions of individuals are routinely engaged in the work of INGOs, whose activities span the whole range of human experience, including agriculture, art, communications, economics, education, environment, health, music, politics, religion, sport and transportation. Additionally, the world has witnessed the growth of an increasingly integrated global economy, as manifested in interdependent national economies and the evolution of multinational corporations (MNCs) and transnational corporations (TNCs) operating in just about every country worldwide. Many of these companies are economic giants, dwarfing all but a few of the world's national economies.

An apparently contradictory worldwide trend towards local identity and ethnicity has also emerged as a major factor shaping events in the world today. In the wake of the end of the old East-West Cold War confrontation, we are witnessing a worldwide increase in local ethnic conflict, sometimes nonviolent but too often violent and very bloody, and often involving a religious dimension. These "local conflicts" are often proving to be intense and intractable, embedded in centuries of mistrust and hatred, and too often crystallized around and sanctioned, implicitly or explicitly, by particular religious institutions.

This localization process is every bit as profound as the overarching trend towards globalization, and in fact it is perhaps best conceived as neither in opposition to, nor separate from, that process. Globalization and localization are so interconnected and interdependent that localization is best conceptualized as an essential complement of the globalization process. This view suggests that the integration of the big system, the creation of a new world order, requires a sense of meaning at the local level, requires human beings to experience coherence and balance within the local socio-cultural context. The rise of fundamentalism, it can be argued, is associated with this interdependence of the globalization and localization processes and the resulting pressures to achieve coherence at the local level in the face of the vast scope of the global supersystems.

The coherence in individuals' lives is, to a greater or lesser degree, associated with culturalization, with what the world means and how meaning in life and death is interpreted. Multicultural interpretations of the globalization - localization interdependency argue, as a consequence, that religion should not be the same in all societies, that it will and must have personal, local and global dimensions that manifest themselves in a rich variety of cultural forms and expressions.

This paper will subsequently further argue that the diversity of organized world religions--if also recognizing a deeper spiritual unity that connects this outer diversity--is a necessary requirement for the creation of a new culture of peace in the 21st century. If, as many believe, the underlying spiritual reality of the world's religions is the same, it can be argued that the cultural expression of that reality in the material world, the world's organized religions, must necessarily be different, in tune with the rich tapestry of our many global cultures, if we are to sustain the dynamic globalization-localization balance in a nonviolent, multicultural form.

3. Principles From the Fields of Intercultural Communication and Conflict Resolution: Tools to Help Deal with Cultural and Religious Diversity

"And the question for today is: 'What is Reality?"-- cartoon caption under a group of aliens or space beings [or people from different cultures or religions] sitting around a table.As noted above, intercultural communication deals with what happens when people from different cultures, including religions, come together to communicate, interact, and even negotiate with each other. Individuals each carry around some different version of "reality" or culture in their heads, based on socialization (or learning) by the different agents or institutions of socialization in their culture, including religion, and based on different individual and collective life experiences. This worldview provides a sense of values and meaning about life. The way that this reality is known is through one's perceptions of it. Unfortunately, perceptions based on evidence from one or more of the five senses are often distorted. Individuals also selectively perceive ideas and information, often accepting information which fits with their preconceived worldview and blocking out information which challenges that worldview--a worldview that they have spent a whole life time putting together.

"The message sent is often not the message received."-- Basic tenet from the field of Intercultural Communication

It is often the case that in everyday interactions individuals, even from the same culture, can misperceive each other. When they come from totally different cultures, including different religious traditions and belief systems, the danger is even greater. It is thus a basic tenet of intercultural communication that "The message sent is often not the message received" It is understandable that individuals tend to expect others to behave the way they would in a given situation or say what they would say in that same situation. When they do not, there is a strong tendency to interpret the motivation or meaning behind the behavior of the other person in terms of what that behavior would mean in one's own culture rather than in terms of what that behavior actually means in the other person's culture, since the other's culture is not really understood. The next step can involve taking a mistaken interpretation of the other person's behavior and then evaluating or judging that behavior, often negatively. This process thus involves moving from a simple factual description of the behavior of someone from another culture, to an interpretation of the meaning of that behavior (often a misinterpretation, based on what that behavior would mean in the individual's own culture, not in the other person's culture.) A final step in this model involves a move to evaluation or judgment of that behavior, as good or bad, in turn often based on an incorrect interpretation. This description, interpretation, and evaluation sequence of events, which individuals do quite often without even realizing they are doing it, is often called DIE for short.

A related theory is Attribution Theory, which hypothesizes that individuals attribute meaning to the behavior of someone from another culture, often based on what it would mean in their own culture, rather than in the context of the other person's culture or religion. As long as an individual remains uninformed about another person's culture or religion, that individual remains vulnerable to repeating this problem over and over in their intercultural and inter-religious interactions. One important component of a solution to this problem is to become better informed about another person's culture and religion so that it is at least possible to interpret another's behavior and words in the proper cultural and religious context within which they occur. Such a strategy will also contribute to an appreciation of the rich cultural and religious diversity that exists in this world and help to counteract the tendencies to judge other's actions and words incorrectly and negatively.

In terms of conflict resolution, it can be argued that if an individual is not conscious of their own cultural or religious socialization or programming--which influences people to a much greater extent than most individuals realize, then their behavior will in many ways be preconditioned, and on automatic pilot: they will be acting out their cultural or religious programming, without being conscious that there are other cultures or religions or ways of experiencing reality. If an individual begins to become conscious of their own cultural or religious programming, often by exposing themselves to other cultures or religions, then they can for the first time come back to their own original culture or religion and begin to see it for the first time, since they now have some basis with which to compare it. Such an individual can begin to act consciously in the world and start to appreciate the rich diversity of the human experience, including the many different outward forms, rituals, and beliefs that have emerged in different religions as human beings have sought different paths for bringing a spiritual force into their lives.

A central problem in intercultural communication, including interactions between peoples from different world religions, is to confuse the map (one's own particular version of culture or religion) with the territory (an ultimate experience of "Reality" or "God" or "Spirit," as opposed to the relative or limited experiences of daily life). Becoming conscious of being socialized into different religions and cultures, coupled with an awareness that individuals as a consequence carry around different versions or maps of "reality" in their heads, can contribute to becoming more tolerant of the different maps or versions of reality that others also carry around in their heads, while also recognizing that something much more basic and essential underlies all the apparent outer diversity.

In looking at diversity, it should also be noted that it is a basic principle of systems theory that the more complex a system is, the more diversity there needs to be within the system for it to maintain itself. The discussion of globalization and localization in the first part of this paper suggests the evolution of a more complex global system with increasing diversity within it. It is a thesis of this paper that such diversity is ultimately a strength, not a weakness, but only if it is consciously dealt with. Otherwise, we will expect people from different cultures to think and behave the way we do, and when they do not, we will tend to misinterpret and then judge their beliefs or behavior negatively (the Description, Interpretation, Evaluation problem discussed above), thus creating misunderstanding and conflict between peoples. Nonetheless, cultural diversity in the global system, like ecological diversity within an ecosystem, is ultimately an asset, if it is valued and contributes to openness to learn from other groups and cultures. Another thesis of this paper is that every culture, just as every religion (or species), has something important to contribute to the world, and no culture has all the answers. Thus every culture has both strengths as well as weaknesses. There are thus important things that we can each learn from each other--if we are open (and humble enough) to do so.

C. ESOTERIC/INNER FORMS OF RELIGION AS DIRECT INNER MYSTICAL EXPERIENCE

1. The Inner, Mystical Path to Spirituality: Many Paths to God

"There are many paths to God." - Common mystical view.According to mystics, the mystical experience focuses on a direct inner experience of God or spirit, in which a person becomes one with the ultimate, invisible, creative force and divine intelligence at work in the universe or with the infinite void beyond creation. Via such an inner experience of enlightenment, God, oneness or spirit, one has an inner "knowing" that cannot be adequately described in words (indeed, "the Tao that can be named is not the Tao"). This experience totally transcends the world of outer beliefs--which we learn from our social and religious institutions. This inner knowing occurs on a much deeper level of one's being and is not vulnerable to all the distortions of our regular five senses, on which we depend for all our learning in the world.

"Look at every path closely and deliberately....Then ask yourself...one question...Does this path have a heart? If it does, the path is good; if it doesn't it is no use." - Carlos Castaneda

"The Tao that can be named is not the Tao." - Lao Tsu

It is interesting that almost every one of the great religions of the world originated with someone who had such a direct, inner revelatiory or enlightenment experience. Jesus who became the Christ, Buddha, Moses, Zoroaster, and various other evolved beings are obvious examples. After achieving enlightenment, such persons (who usually did not themselves intend to start a new religion) have always returned to society to minister, teach, and share their spiritual experiences and enlightenment as best they could with others. Eventually, the original teacher/ Master passed on and the followers were left to interpret, and later record, the original founder's teaching. But these followers have often not had the same enlightenment experiences themselves, and so with time, the original teachings became codified as beliefs, rituals, even dogmas. In this way, an original esoteric, mystical experience is changed over time into an exoteric form of organized religion. Nonetheless, since most people begin their spiritual path with some exoteric form of religion, it can be hoped that with time, at least some of these people will eventually turn inward to seek and experience the truth of God or spirit within.

While all religions usually began with someone who became enlightened, it is also interesting that mystical traditions continue to be dominant in Eastern religions, but were often overshadowed, though not lost, in Western religions by a focus more on organized religion and learned beliefs and principles to live by in the world. Nonetheless, there has been an interesting recent revival of interest in mystical/spiritual traditions in the West, along ironically with equally strong or stronger fundamentalist movements. Perhaps this indicates the great desire in people to find some deeper meaning to their lives, amidst all the changes in their external lives and in the world, although by sometimes very different paths. Such a hypothesis would be consistent with the globalization-localization hypothesis discussed earlier.

It is also interesting that while the traditional, exoteric religious path requires learning about different practices and beliefs, the mystical, esoteric path often involves unlearning or using various meditative techniques to clear the mind of thoughts about the external world, so that it is possible to come to a place of inner stillness or emptiness of the external world--what Zen Buddhists call "No Mind." This still, inner state enables individuals to experience the godforce, spirit, or pregnant void within, without the distortions of everyday needs, beliefs, and limited consciousness intervening, and thus to go beyond the limited self or ego so that spirit can make itself manifest in their lives. Thus many mystical traditions focus on ways to quiet the overactive mind in meditation, and thus bring one's inner self to a state of peace.

In such spiritual traditions, only true inner peace within the hearts of people can bring about true outer peace in the world, because if individuals are plagued by inner conflicts, doubts, fears, and insecurities, they will tend to project them outwardly onto others, blaming others for their problems, without even realizing what they are doing. It is thus necessary for all of us as individuals to 'wake up' and become increasingly conscious of our own thoughts and feelings, and how these are creating certain results or consequences in the world, so that we may each become increasingly responsible for the type of world that we are creating--including whether this world is a peaceful one or not.

2. Parallels Between New Scientific Paradigms and the Mystical Experience

"Religion without science is blind. Science without religion is lame." -- Albert EinsteinThere are a number of new paradigms, or overarching worldviews, under which scientists conduct their research, in science today. These paradigms can be seen as differing versions of a dynamic, interdependent, whole systems worldview, which various writers have suggested parallels the mystical, spiritual experience of mystics from different religions around the world. (Capra, 1991; Capra, 1982; Chopra, 1990; Davies, 1992) In effect, mystics experience this dynamic, interdependent, whole systems worldview on the inner planes, while scientists have used scientific methods and analysis of the external world to arrive at related conclusions. It can be argued that the scientific and the spiritual paths are just two different ways of trying to study or know the same ultimate reality; that one can go infinitely outward scientifically into space and infinitely inward spiritually in meditation, and that ultimately these two paths converge with parallel worldviews. Nonetheless, it needs to be pointed out that physics or science can only study or measure reality within the space-time framework of the created, physical universe. Science itself cannot provide the mystical experience of the mystery or ultimate beyond space & time, which may be one reason why the greatest scientists all eventually became mystics themselves, including DeBroglie, Einstein, Eddington, Heisenberg, Jeans, Plank, Pauli and Schrodinger. (Watson, 1988; Davies, 1992)

"The most beautiful thing we can experience is the mysterious. It is the source of all true art and science." -- Albert Einstein

The old, Newtonian paradigm in physics saw reality as a clockwork universe made up of separate parts, existing within a static or equilibrium model of reality, which operated by fixed laws that could in theory predict how A effected B. This paradigm sought the ultimate physical building blocs of matter and was based upon the assumption that science, in principle, could arrive at total truth or understanding of reality within its' materialistic, reductionist, mechanistic worldview. In contrast, the New Physics has a totally new worldview, based on Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity and then later his General Theory of Relativity, followed by Quantum or Subatomic physics. With regard to quantum physics, however, it is interesting that Einstein himself could not totally accept Heisenberg's "uncertainty principle," expressed in Einstein's famous saying: "God does not play dice with the universe" or allow unpredictability. Thus Einstein himself only accepted part of what has come to be called "the New Physics."

Before noting further characteristics of the new paradigm view of reality in the New Physics, it should be noted that this new paradigm does not negate the Old Physics paradigm. Instead it says that the old Newtonian worldview works within certain parameters, and is thus still valid within those parameters, but beyond those parameters a new paradigm is necessary. Likewise, with the other new scientific paradigms (discussed further below), there is a tendency at times to conclude that they make the older scientific paradigms totally obsolete, but this is seldom the case and needs to be stressed. The old paradigms still work within certain parameters and under certain conditions, while the new paradigms work beyond those parameters, when the underlying conditions change. Recognition of this fact is part of creating a balance between different world views, and knowing when each is appropriate, that is a primary thesis of this whole paper.

The characteristics of this new paradigm--which in physics exists especially on the very macro level of the whole universe and on the very micro subatomic levels--are as follows. The New Physics (according to Capra, Davies and others) includes a dynamic, interdependent, whole systems worldview, where matter is concentrated energy and there are no ultimate building blocs of matter to find. In addition, one cannot predict an absolute relationship between A and B, and one cannot predict ahead of time whether something will, for example, be a particle or a wave. Unlike the old paradigm where the scientist was a pure, theoretically objective, outside observer, the new paradigm admits that the scientists' presence in the situation, in making a scientific measurement, can affect the outcome of the measurement, and thus there is no such thing as a purely detached objective, scientific observer anymore, instead one's mere presence in a situation can effect the outcome. The new paradigm is thus holistic, dynamic, and interdependent; there are no separate parts, only relationships; and reality is not totally predictable, except in terms of statistical probabilities. The old paradigm focuses on analysis of separate parts and either/or thinking (beginning with Aristotle), while the new paradigm focuses on synthesis and dynamic interrelationships, as well as both/and thinking.

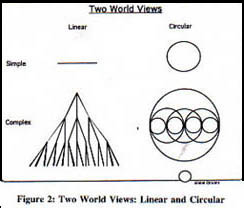

In addition to the New Physics, there are other new scientific paradigms in science that also exhibit this dynamic, interdependent, whole systems worldview, as opposed to the old paradigm view of reality as a static, equilibrium model, which saw reality as made up of separate, unconnected parts, in a mechanistic, reductionist worldview. (See Figure 2) Some of these other new scientific paradigms follow below.

Whole, dynamic systems and living systems paradigms are illustrated in the work of the Society for General Systems Research. Evolutionary paradigms--such as those of Teilhard de Chardin, Peter Russell, Barbara Marx Hubbard, Erich Jantsch, John Platt, Erwin Lazlo, and Stephen Jay Gould's Puctuated Equilibrium Theory in biology--see change within a system as sometimes taking quantum jumps. Ilya Prigogine's Nobel Prize winning Theory of Dissipative Structures--which reconciles the entropy of physics with the increasing order and complexity of biology--shows how open systems can change via perturbations or new energy of some kind within a system, which can cause that system to break down, releasing the energy of that system to be reorganized at a higher level of order and complexity.

Rupert Sheldrake's Hypothesis of Formative Causation, or Theory

of Morphogenetic Fields, hypothesizes that the universe operates more by habits,

that build up over time, than by fixed laws. Under this theory, the first time

a member of a species does something new is the hardest, but each successive

time this new behavior becomes easier, until finally a critical mass is reached,

and then suddenly everyone in the species knows how to do that new behavior.

James Gleick's Chaos Theory hypothesizes that everything in the universe is

interconnected--a butterfly flapping its wings in one hemisphere can effect

the climate in another hemisphere, for example--and there is always order emerging

out of chaos and chaos emerging out of order in the universe.

It is significant is that all of these new paradigms and scientific

theories are versions of a dynamic, interdependent, whole systems worldview,

just as the New Physics is. In medicine and health care, new notions of health,

healing and treating the whole person are fast gaining ground. (Chopra, 1992)

In environmental science, the Gaia hypothesis presents a new paradigm where

the Earth as a whole is seen as a living entity, a self-regulating system of

which we humans are a part. (Lovelock, 1991) In the life sciences, new thinking

is challenging traditional notions of biological evolution and developing new

interdependent conceptions of what constitutes a person and a society. (Watson,

1988) In each of these cases, as well as in many other examples of the development

of new thinking in areas such as management and economics, (Wheatley, 1992;

Hawley, 1993) the relationship and interaction between parts and the whole has

been reconceptualized. Holistic paradigms, where the overall pattern of interaction

between the parts is as important as the parts themselves, have emerged across

a broad spectrum of disciplines and issues.

3. How a Dynamic, Interdependent, Whole Systems Worldview (of the Mystic or Scientist) Can Help Contribute to a Global Culture of Peace

"Everything has changed except our way of thinking." --Einstein

"Oh, Great Spirit, let us greet the dawn of each new day, when all can live as one and peace reigns everywhere." --Native American Quote

The relevance of "new thinking" or a shift in consciousness--as

seen in the dynamic interdependent, whole systems views in the new scientific

paradigms and experiences of mystics from different religious traditions--to

world peace can be seen as follows. Once our consciousness shifts from seeing

the world as divided up into separate, unrelated parts (whether individuals,

groups, nation-states or whatever), where the goal is to win for one's own self

or group or nation, without adequate concern for others, to a new more dynamic

interdependent, whole systems worldview, where everything is interconnected,

and whatever happens in any part of the system effects all the other parts of

the system--it becomes apparent that the only way that individuals or separate

parts of the whole can "win" is if other peoples and parts of the

whole also win. A fundamental shift from win-lose to win-win thinking then ensues,

which seems a fundamental prerequisite and framework for creating a global culture

of peace.

PART II: FURTHER EXPLORATIONS OF THE ESOTERIC/INNER

AND

EXOTERIC/OUTER ASPECTS OF RELIGION AND CULTURE

A. ALTERNATION BETWEEN IDEATIONAL/SPIRITUAL/INNER AND SENSATE/MATERIALISTIC/OUTER FORMS OF WESTERN CULTURE: THE WORK OF PITIRIM SOROKIN

1. Functional and Logico Meaningful Integration of Cultures

The previous section of this paper described some of the new paradigms,

which are emerging in a range of areas. It can be argued that it is no accident

that these holistic paradigms have developed at this time. Indeed, one of the

founding fathers of peace research, Pitirim Sorokin, suggested some 60 years

ago that this would be the case. (Sorokin, 1933) Sorokin, in his classic text,

Social and Cultural Dynamics, elaborated a theory of socio/cultural evolution

that can be summarized as follows.

In any society or social system, there are four ways in which

integration can occur. Two of these are for our purposes here quite trivial,

namely spatial integration (when entities simply occupy the same space and nothing

more) and external integration (when two or more entities are linked to each

other through some other entity, for example grass and flowers may grow together

at the same rate because of the external factors of sun, soil and rain). The

third, functional integration, is far from trivial. This, for Sorokin, describes

the interlocking interdependencies we now recognize as crucial in complex systems.

Indeed for many scientists "functional integration," or its modern

cybernetic equivalent "syntegration," (Beer, 1993)--the dynamic interdependence

of entities that are in symbiotic interaction with each other--is of the utmost

importance. Whole societies, whole systems, are held together by their mutually

interdependent functional interactions and, following Wright's model, any changes

in one will need changes elsewhere in the system to restore dynamic equilibrium.

Sorokin also proposed a fourth level of integration, which, in

his view, was the highest form of integration. He called it "logico meaningful

integration," to try to describe the underlying idea that things are held

together because of what they mean, because of deep values in the culture. Sorokin

argued that this level of integration not only provides coherence in life to

individuals through the underlying meanings in their culture, but also results

in these deep values being manifest in all aspects of a culture, from science

to religion. For Sorokin, a culture at its peak will be integrated in both functional

and logico-meaningful ways. He approached the problem of meaning in the following

way.

2. Sensate/Materialistic, Ideational/Spritual, and Idealistic/Mixed Cultures

Sorokin argued that the macro cultures in Western Civilization

evolved through stages that could be understood in terms of their central meanings.

At one end of a continuum, these underlying meanings were essentially sensate,

that is reality was defined entirely in terms of the physical world and the

truth of the senses. At the other end, reality was "ideational," by

which Sorokin meant spiritual in the sense that the eternal infinite spiritual

reality is real, while the material world is an illusion. In this case truth

of faith is the only truth. Halfway along this continuum was the "idealistic"

point, where truth of faith and truth of senses were balanced through "truth

of reason." Sorokin identified seven types of culture mentality on the

sensate-ideational continuum. Table 1 gives the main elements of the sensate,

ideational and idealistic forms.

Table 1: Three Types of Culture Mentality

(Sorokin):

Active Sensate, Ascetic Ideational, and Idealistic (Combining Both) |

|||

Active Sensate

|

Ascetic Ideational

|

Idealistic

|

|

Reality

|

Sensate, material, empirical

|

Non-sensate, eternal transcendental

|

Both equally represented

|

Main needs and ends

|

Manifold and richly sensate

|

Spiritual

|

Both equally represented

|

Extent of satisfaction

|

Maximum

|

Maximum

|

Great, but balanced

|

Method of satisfaction

|

Modify external environment

|

Self modification

|

Both ways

|

Note: Sorokin elaborated seven types of culture mentality. The

three listed above are the two extremes--Active Sensate and Ascetic Ideational,

as well as a middle point, the Idealistic culture type.

Table 2: Three Types of Culture Mentality

(Sorokin):

Weltanschauung, Power and Object of Control, and Activity |

|||

Active Sensate

|

Ascetic Ideational

|

Idealistic

|

|

Weltanschauung(or World View)

|

Becoming:

Transient values, full blooded sense of life, joy and grief; dynamism and endless readjustment ; progress, evolution |

Being: Lasting value; indifference to transient values;

imperturbability; statism

|

Both equally represented

|

Power and Object of Control

|

Control of the Sensate Reality

|

Self Control, repression of the sensual person and of

"self"

|

Both equally represented

|

Activity

|

Extrovert

|

Introvert

|

Both equally represented

|

Table 2 outlines the logico meaningful consequences of the three

types of culture mentality for weltanschauung (or worldview), power and object

of control, and activity. For Sorokin, the "logical satellites" are

aspects of the culture that follow logically from the central integrating principle

of the culture. In Sorokin's words, "each of them (the logical satellites)

is connected logically with the dominant attitude toward the nature of ultimate

reality." Thus the active sensate culture is based on "becoming",

based on a full-blooded sense of life and continual change. Ideas such as progress

and evolution are central to such a viewpoint. In addition, the dominant ideas

on control stress control of the external sensate reality and hence activity

in the outer world. In contrast, the ideational culture is based on "being",

stressing lasting value. In addition, self-control and repression of the sensual

person and of self lead to a focus on the inner life. Idealistic culture for

Sorokin is an attempt to balance both worldviews, to live in both the inner

and outer worlds, and balance being and becoming, control of the external environment

and control of self.

Table 3: Three Types of Culture Mentality

(Sorokin):

Self and Knowledge |

|||

Active Sensate

|

Ascetic Ideational

|

Idealistic

|

|

| Self |

Highly integrated, sensate, dissolved in immediate physical

reality; materializes self and all spiritual phenomenon; cares for integrity

of body and its sensual interest (sensual liberty, sensual egotism)

|

Highly integrated, spiritual, dissolved in the ultimate

reality; aware of the sensual world as illusion; anti-materialistic

|

Both equally represented

|

| Knowledge |

Develops science of natural phenomena and technical

inventions; concentrates on these; leads to arts of technology, medicine,

hygiene, sanitation and modification of peoples' physical environment

|

Develops insights into and cognition of the spiritual,

psychical, and immaterial phenomena and experiences; concentrates on these

exclusively; leads to arts of education and modification of inner life

|

Both equally represented

|

Table 3 details how each culture mentality affects what is meant

by "self" and what is defined as knowledge in each type of culture

mentality. Both the sensate and ideational types are highly integrated around

completely different reality definitions. The sensate culture is associated

with a view of the self as a material entity dissolved (or living totally) in

the immediate physical reality. Under this view the material world provides

the basis for everything, and materialistic models of reality are likely to

be dominant in all compartments of culture. Mechanistic models of the universe

and materialistic biochemical models of health are typical examples of the sensate

view of reality, a view that stresses caring for the physical body, sensual

liberty (for example, sexual freedom) and sensual egotism (for example, cultivating

the body beautiful). Such a worldview will naturally develop physical and biological

sciences that study and manipulate the external world, and in so doing will

develop technology for this purpose. In contrast, the ideational culture type

searches for the inner self, which is experienced as dissolved (or existing

totally) in the ultimate spiritual reality. The external material world is seen

as an illusion, and knowledge of the spiritual, psychical and immaterial reality

becomes the basis for knowledge. Using meditation and other self exploration

approaches, knowledge of the inner self, including inner peace, becomes central.

As in the case of Table 2, the idealistic culture mentality attempts to balance

both approaches.

Table 4: Three Types of Culture Mentality

(Sorokin): Truth, and Moral Values and Systems

|

|||

Active Sensate

|

Ascetic Ideational

|

Idealistic

|

|

| Truth: its categories, criteria, and methods of arriving at |

Based on observation of, measurement of, experimentation

with, exterior phenomena through exterior organs of senses, inductive

logic

|

Based on inner experience, "mystic way," concentrated

mediation, intuition, revelation, or prophecy

|

Both equally represented (scholasticism)

|

| Moral values and systems |

Relativistic and sensate; hedonistic, utilitarian; seeking

maximum sensate happiness for largest number of human beings; morals of

rightly understood egotism

|

Absolute, transcendental, categoric, imperative, everlasting,

and unchangeable

|

Both equally emphasized

|

Table 4 illustrates the approaches to truth and to moral values

in the three culture mentalities. Thus the active sensate culture is based on

"truth of the senses," where truth is validated through observation

of, and experimentation with, the external environment. The five human senses

are ultimately the basis for establishing truth, and inductive logic is used

to relate the evidence from the senses to models of reality. The moral value

system of the sensate culture is relativistic and utilitarian, based on maximum

sensate happiness. In contrast, the ideational worldview is based on "truth

of faith," whereby the inner experience of the ultimate reality, the mystical

experience discussed above, is achieved through concentrated meditation, intuition,

revelation, or prophecy. This ideational culture mentality is based on absolute,

transcendental values, values that are God-given, imperative, everlasting and

unchangeable. The idealistic culture mentality stresses both "truth of

the senses" and "truth of faith" in a truth system that Sorokin

calls "truth of reason." Greek culture around the 4th and 5th centuries

BC and European culture around the 12th to14th centuries AD are seen by Sorokin

as examples of this balanced cultural form. Idealistic culture similarly includes

a both/and approach to moral values, incorporating both perspectives in its

value system.

Table 5 illustrates the characteristics of the three culture mentalities

as these relate to aesthetic values and social values. In the sensate culture,

art and aesthetic values are based on increasing the joys and beauties of a

rich sensate life, while social and practical values give joy of life to self

and partly to others. In particular, they stress the value of monetary wealth

and physical comfort. Prestige in society is in large measure based on these

factors. In conflicts, physical might is more important than being right in

the moral sense. The ideational culture type sees aesthetic values as being

servants to the main inner values, which are essentially religious and non-sensate.

For social values, only those which serve the ultimate inner spiritual reality

are of value, while materialistic values, such as economic wealth, are seen

as ultimately worthless. The principle of sacrifice is an integral part of the

ideational social value system. As in the above cases, idealistic culture attempts

to balance sensate and spiritual concerns.

Table 5: Three Types of Culture Mentality

(Sorokin)

|

|||

Active Sensate

|

Ascetic Ideational

|

Idealistic

|

|

| Aesthetic Values and Systems |

Sensate, secular, created to increase joys and beauties

of a rich, sensate life

|

Ideational, subservient to the main inner values, religious,

non-sensate

|

Both equally emphasized

|

| Social and Practical Values |

Everything that gives joy of life to self and partly

to others: particularly wealth, comfort, etc.; prestige is based on the

above; wealth, money, physical might become "rights" and basis

of all value: principle of sound egotism

|

Those which are lasting and lead to the ultimate reality:

only such persons are leaders, only such things and events are positive,

all others are valueless or of negative values, particularly wealth, earthly

comfort, etc.; principle of sacrifice

|

Both equally emphasized; live and let live

|

Sorokin and his helpers collected and coded huge amounts of information

on various aspects of Western macro culture, including indicators of sensate

and ideational worldviews, in art, science, mathematics, architecture, discoveries

and inventions, philosophy, ethics and jurisprudence. Using this data, he argued

that there was a tendency, over long periods of time, for Western macro culture

to swing from one end of the continuum to the other in their central meanings,

and that these changes in central meanings are manifest in all aspects of an

integrated culture. A crude summary of his findings are presented in Table 6.

The still evolving Western civilization, in Sorokin's view, had

achieved overripe sensate status (with too much stress on materialism and an

almost complete disregard for spiritual values) and was now in crisis, swinging

back towards the ideational pole. Such a swing would inevitably manifest itself

in the emergence of "new holistic paradigms" in many different areas,

as illustrated above, as well as in the re-emergence of ideational, religious

or spiritual worldviews. It will also, in Sorokin's view, lead to a period of

turmoil, crisis and catharsis, from which the new ideational or idealistic culture

will emerge.

Table 6: Fluctuation of Truth Systems

in Graeco-Roman

and Western Civilization (Sorokin) |

|

| Period | Classification |

| Up to the 5th Century B.C. | Ideational |

| 5th and 4th Centuries B.C. | Idealistic |

| 3rd to the 1st Century B.C. | Sensate |

| 1st to end of 4th Century A.D. | Transition & Crisis |

| 5th to 12th Centuries A.D. | Ideational |

| 12th to 14th Centuries A.D. | Idealistic |

| End of 14th Century to 15th Century A.D. | Transition & Crisis |

| 16th through 20th Century A.D. | Sensate (Active, then passive, now cynical, entering transition) |

3. Relevance of Sorokin's Ideas to the World Today:

Every model of reality--including Sorokin's--is a simplification

of reality to some extent. In various ways, the global situation today is more

complicated than Sorokin's model suggests, since the world is also more complex

than when he wrote. There are, for example, multiple interactions between different

cultures occurring in the world today, which are not in Sorokin's model. Despite

this fact, it is nonetheless interesting that a number of new, holistic scientific

paradigms and worldviews are emerging today in a number of different areas--just

as Sorokin predicted 65 years ago would happen as part of a return to more spiritual

values in Western cultures today. There is, however, within the scientific community

itself, some difference of opinion over whether the new, holistic scientific

paradigms deal only with the physical world, or whether they also parallel holistic

spiritual values and experiences of reality. The latter view was the thesis

of Fritjov Capra's book, The Tao of Physics, for example, but not all physicists

agree with Capra.

Similarly, the Gaia Hypothesis is interpreted by some in a purely

"functional" integration sense (K. Boulding, 1990) and by others within

a spiritual framework, suggesting "intentionality" and an "intelligence"

behind the way Gaia operates. (Ruether, 1992; Badiner, 1990) James Davies, who

has written various books popularizing the New Physics, also asks: "Why

are the laws of nature mathematical?" and why can nature everywhere be

explained by mathematics, thereby allowing science to understand nature? To

Davies, the fact that we can study and understand the universe at all, and that

science is even possible at all, implies that the universe is not a random event,

but rather that intentionality and purpose are behind its creation and design.

(Davies, 1992) Other scientists also note the extremely low statistical probability

of life--including self-conscious, self-aware, intelligent life (as represented

by humans)--evolving on earth, which to some scientists implies an intentionality

or purpose behind our physical universe, its creation and the design of its

evolution. The fact that life itself seems to evolve towards ever more intelligent

self awareness--whether in human form on earth or other possible forms elsewhere

in the universe--implies a designer behind the design to some scientists. In

summary, new holistic, scientific paradigms are emerging across a variety of

fields, and increasing numbers of people are seeing connections between the

spiritual and material aspects of these paradigms.

In looking at Sorokin's two opposite types of cultures--sensate/materialistically-based

cultures, and ideational/spiritually-based cultures--and his thesis that Western

history has alternated back and forth between these two extreme cultural types,

with periods of balance between them during certain transitional times, several

interesting questions and observations arise in regard to how these two opposite

cultural types, and the transitions between them, relate to the contemporary

world and to the world of the 21st century?

(1) First, it is amazing how Sorokin's two polar opposite cultural

types--sensate and ideational cultures--which alternated in Western history,

seem to perfectly describe what we commonly think of (at least in a generalized,

archetypal way) as characteristics of Western cultures (sensate/materialistic)

and Eastern cultures (ideational/spiritual).

(2) However, if we now think of Western cultures as predominantly

materialistic, but note that Western culture has also had non-materialistic,

spiritual periods in its history, then perhaps Eastern cultures, which we tend

to think of as more spiritual, have also had periods of materialism and a predominance

of sensate values at certain periods in its history as well? Sorokin's work

focused primarily on Western cultures, so further research needs to be done

by others today on this question. Nonetheless, it should be noted that the work

that Sorokin did do on Eastern cultures tended to describe them predominantly

as ideational/spiritually-based cultures. As Sorokin himself concluded: (Sorokin,

1957, p. 43)

....the Ascetic Ideational culture mentality comprises not an

island but several of the largest continents in the world of culture. The systems

of mentality of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Taoism, Sufism, early Christianity,

and of many ascetic and mystical sects, groups, and movements (i.e., the Cynics,

Stoics, Gnostics, and the devotees of Orphism) have been predominantly Ideational,

Ascetic Ideational at the highest level, Active Ideational on a lower, and Idealistic

and Mixed on the lowest.

(3) If we tend today (in our common images and stereotypes) to

think of Western cultures as primarily sensate/materialistic, and Eastern cultures

as primarily ideational/spiritual, then it needs to be noted that the actual

world of today is more complex than this. Indeed, there are powerful forces

of change sweeping the planet today. In many ways, Eastern cultures (represented

especially by Asian countries) are undergoing rapid economic development, technological

growth, and increasing materialism as a result. This has led many thoughtful

people to be concerned that the whole world is perhaps becoming Westernized

and materialistic. But an equally strong counter current is also occurring within

Western cultures today, where the achievement of a certain level of material

comfort often leads people to seek other values in life, especially spiritual

values, in an effort to find meaning. Spiritual and religious movements of various

kinds are thus having a comeback--especially in cultures and countries that

have undergone the greatest degree of material development, i.e., North America,

Europe, and Japan. This is no accident. Indeed, it can be argued that both Western

and Eastern cultures, in their pure or extreme forms (to the extent that they

did actually at times represent one of Sorokin's two opposite cultural types),

have traditionally both been out of balance, and that today, for the first time

our increasingly interdependent world is providing the conditions for both Eastern

and Western cultures to become more in balance, in terms of honoring both spiritual

and material values, inner peace as well as outer peace values, and group as

well as individualistic concerns and perspectives, and that this is indeed the

most promising development occurring in the world today, in regard to creating

the foundations for a global culture of peace--for both East and West--in the

21st century.

(4) Nonetheless, it needs to be pointed out that periods of transition--when

the underlying values on which a culture and civilization have been based are

undergoing rapid change and being challenged--are very disruptive to people's

lives and to the effective functioning of one's societal institutions. And indeed,

we see that this is happening today. Crime and violence are on an increase everywhere.

Fanatics of the left and right--including religious cults promoting violence

in the name of God or spirit (a total contradiction in terms)--are multiplying.

The transition period does not guarantee an easy ride. But change is inevitable,

and it must be dealt with as constructively and consciously as possible, so

that we can get through this transition period with as little real catastrophes

and violence as possible.

(5) Then, assuming that such a new, balanced culture of peace

can be created in the world in the 21st century (a big assumption, we grant

you), how long could such a balanced inner-outer, spiritual-materialistic, female-male

balanced culture be able to endure? Sorokin's work suggests--at least based

on his analysis of the alternations in Western cultures historically--that such

balanced Idealistic periods usually lasted about 200-300 years. In non-Western

cultures, Sorokin saw Confuscianism and much of Ancient Egyptian culture (which

lasted 3,000 years) as good examples of the balanced, Ideational form. As Eastern

and Western cultures increasingly come together and interact with each other,

now and in the future, perhaps such a balanced period could last for a long

time--drawing on both Eastern and Western cultural values for its maintenance

and sustenance. If that were to become possible, then the so-called "Golden

Age" (prophesied in various religious and spiritual traditions) could indeed

become a reality.

(6) A less desirable alternative to this balanced scenario would

be if Western cultures move increasingly towards an ideational, spiritual value

system, while Eastern cultures move increasingly towards a sensate, materialist

value system, with East and West, in effect, changing places! This might be

more likely if both Eastern and Western cultures could continue to develop in

isolation from each other, but in our increasingly interdependent world, this

seems unlikely. The more preferable, balanced scenario, however, would be for

the East to increasingly develop economically--as it no doubt will do, with

many economic observers having called the 21st century the "Pacific Century--while

still maintaining and preserving its rich spiritual traditions and values, and

for the West to increasingly further an interest in spiritual, inner peace questions,

while still maintaining a decent materialistic lifestyle and concern with social

justice issues in the outer world.

(7) We will no doubt have to wait and see what we all individually

and collectively decide to create. The transition period of getting there may

indeed be rocky. But a peaceful world, based on attention paid to both inner

peace and outer peace, including social justice questions, is indeed one possibility

for the 21st century.

B. MALE AND FEMALE ASPECTS OF DIVINITY IN DIFFERENT RELIGIONS AND CULTURES

1. In Different Cultures and Historical Periods, People Have Believed in Nature Spirits, Goddesses, Gods and Goddesses, and in One God (Often Interpreted as Male)

At different times in history, and in different cultures, divinity

or the sacred or spiritual has been represented in different ways: sometimes

as nature spirits (such as Shintoism in Japan, American Indian traditions, as

well as other indigenous people's spiritual traditions, such as the Aborigines

in Australia); sometimes as goddesses, often associated with fertility and the

earth (seen in the ancient temples in Malta or the Old Europe documented by

Marija Gimbutis); sometimes as a balance between male and female gods and goddesses,

each representing different aspects or attributes of the one God, (as in Ancient

Egypt and Hinduism); and sometimes as a monotheistic, all powerful God who is

often portrayed as God the Father or male (in Western monotheistic religions,

including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam).

There are a number of books that have been written in recent years--many

by feminists who are trying to recapture the spiritual and societal role of

women historically--about the factors leading to the above transition from female

goddess to male God. (Please consult the Bibliography for a few of these recommended

sources, such as Anne Baring and Jules Cashford, Elise Boulding, Riane Eisler,

Marija Gimbutas, David Leeming and Jake Page, Shirley Nicholson, and Merlin

Stone. ) There is not space here to explore this subject in greater depth. The

important point here is just to note that divinity has been portrayed and experienced

differently, at different times in history and in different cultures. Underneath

this diversity, however, was a common search for some kind of spiritual meaning

in life--whatever the form that this took, which one could argue was at least

partly a reflection of the dominant cultural values that existed at the time.

2. In Essence Spirit or God (in Mystical Traditions of All Religions) Transcends Polar Opposites or Dualities (Often Portrayed Symbolically as Male and Female)

It is not the purpose of this paper to argue that one symbol system

for spirit or divinity is correct and others are wrong. All sought to honor

spirit in some way. If God or spirit is beyond all dualities, however--which

the mystical traditions of all religions seem to suggest--then clearly God or

spirit or divinity is also beyond our human attempts to categorize it as either

all male, or all female, at the exclusion of the other. As Lao Tsu said, "the

Tao that can be named is not the Tao." Yet in our limited consciousness,

and in our effort to create a personal relationship with what is essentially

beyond form, infinite, and partaking of the great mystery, we tend to personify

god or spirit--in different ways at different times and places historically.

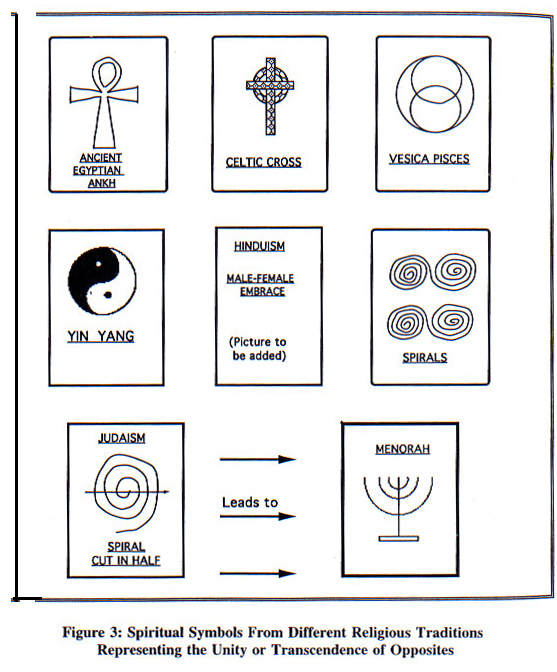

One of the themes of this paper is that if we want to create peace in the world, then we need to find a way to include all the parts of the whole, or the world, in this process. It would thus seem in keeping with this theme that divinity or spirit should be seen to be the unity that transcends all opposites or dualities, however they are represented. In support of this idea, Figure 3 cites examples of spiritual symbols from a number of different religions in the world, which are all based on this idea of recognizing that the spiritual path involves balancing and transcending polar opposites, or dualities. Indeed, the mystical or esoteric path in all religions is based on this simple truth: unitive consciousness transcends duality.

One of the themes of this paper is that if we want to create peace in the world, then we need to find a way to include all the parts of the whole, or the world, in this process. It would thus seem in keeping with this theme that divinity or spirit should be seen to be the unity that transcends all opposites or dualities, however they are represented. In support of this idea, Figure 3 cites examples of spiritual symbols from a number of different religions in the world, which are all based on this idea of recognizing that the spiritual path involves balancing and transcending polar opposites, or dualities. Indeed, the mystical or esoteric path in all religions is based on this simple truth: unitive consciousness transcends duality.

Explanations for the Symbols in Figure 3:

Ancient Egyptian Ankh: Represents the unity of opposites, which

are symbolized by the two halves of the Ankh: the top, circular part representing

the female principle; the bottom straight part representing the male principle.

The Ankh also symbolized eternal life and immortality (with the balancing and

transcending of opposites--represented by the male and female principles--being

the way to get there), as well as the union of Upper and Lower Egypt (the upper

half representing the Delta region of Lower Egypt and the bottom half representing

the rest of the Nile River that flowed through Upper Egypt, in the South, to

the Delta in the North).

(Please Note: if the reader is aware of additional symbols, from

different religious traditions, illustrating this idea of the unity of opposites,

the writers would appreciate hearing from you about this. Thank you.)

Celtic Cross: The Celtic Cross is an interesting Christian cross

in that it combines the traditional symbol of the cross (representing Christ

on the cross, who died to the physical life and was resurrected into eternal

life with the Father--more a representation of the male principle) with the