My father's family came to Newfoundland as fishers (via France via Ireland) in 1632 - it was a horrific hard life.... Lawn, Placentia Bay-

Lifestyle of Fishers, 1600-1900- NEWFOUNDLAND

European fishers had been working off Newfoundland and Labrador's coasts for about 100 years by the turn of the 17th century. Most arrived by May or June to exploit abundant cod stocks before returning overseas in the late summer or early fall. Known as the transatlantic migratory fishery, the enterprise prospered until the early 19th century when it gave way to a resident industry.

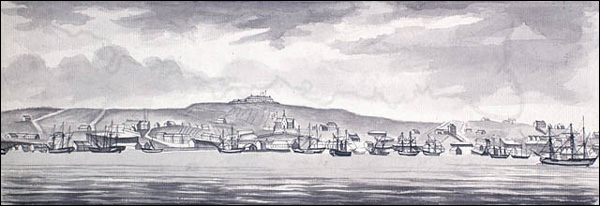

St. John's, NL, 1786

“A View of St. John's and Fort Townsend.” Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada (R5434 C-002545).

Despite these developments, many similarities remained between fishers in the 19th century and their 17th-century counterparts. Handlines, small open boats, and other gear remained largely unchanged since the days of the migratory fishery, as did the basic techniques of salting and drying fish. Inshore fishers of both the 17th and 19th centuries lived in coastal areas that were close to cod stocks, and they rowed to fishing grounds each morning before returning home in the evening or night.

Migratory Fishery

The migratory fishery was a seasonal industry that required most of its workers to live in Newfoundland and Labrador on a temporary basis only, usually during the spring and summer when cod were plentiful in offshore waters. France, Spain, and Portugal participated in the early migratory fishery, but it was England that eventually dominated the industry, each year dispatching shiploads of fishers from its West Country ports.

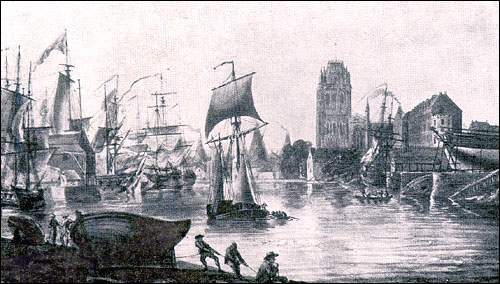

Bristol, England, 1787

England's West Country eventually dominated Newfoundland and Labrador's early migratory fishery.

Painting by Nicholas Pocock. From Stanley Hutton, Bristol and its Famous Associations (Bristol: J.W. Arrowsmith, 1907) 21.

As a result, most fishers working at Newfoundland and Labrador in the 17th and 18th centuries were not permanent residents. They instead travelled across the Atlantic each year in large ocean-going vessels and spent only a few months overseas before returning west in the late summer or early fall. During this time, the vast majority of fishing people were separated from their families and their homes. Most were in the employ of West Country merchants, who traded goods and credit to fishers in return for cod; the merchants then sold the fish to domestic and foreign buyers.

Lifestyle of Migratory Fishers

While at Newfoundland and Labrador, the lifestyles of migratory fishers revolved around their occupation; workers spent most of their waking hours catching and curing fish, which left them with little leisure time. Immediately after arriving in the spring or early summer, workers had to first spend much time and energy cutting timber and building the infrastructure of the fishery: stages, which fishers used to tie up their boats and unload their catch; flakes, where fishers laid out their cod to dry; and cabins, cookrooms, and other structures where workers slept, ate, and retreated for shelter. Workers built camps in coastal areas that would ensure easy access to productive fishing grounds.After the construction phase was completed, fishers spent the remainder of their time at Newfoundland and Labrador catching cod and processing it for sale. Workers rowed to fishing grounds in small open boats early each morning and returned to shore when their vessels were filled with cod. The men fished with long handlines – sometimes up to 55 metres long – that had a hook attached to one end. Fishers baited the hook with squid or capelin, dropped it in the water, and repeatedly pulled the line up and down to attract cod, often having to re-bait the hook.

Fish Hook, ca. 1675

Migratory fishers at Newfoundland and Labrador caught cod

with long handlines that had a small iron hook (like the one shown here)

attached to one end. Fishers baited the hook with squid or capelin,

dropped it in the water, and repeatedly pulled the line up and down to

attract cod.

Courtesy of the Department of Archaeology, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John's, NL.

Labourers in the migratory fishery worked long hours – often from daybreak until dusk. Whatever leisure time they had was likely spent with colleagues, as most men were separated from their families and lived in makeshift cabins. Storytelling and music may have been popular pastimes that would have allowed many people in the group to take part. Fishers also met at the local smithy each evening to drink, smoke, and socialize. Blacksmiths existed in many harbours during the 17th century to repair and manufacture boat fixings and other metal items. Their workplaces, known as smithies or forges, were much warmer than most other local structures and often doubled as taverns in the evenings. Archaeologists at Ferryland have uncovered a wide range of clay pipes and ceramic drinking vessels in a local 17th-century smithy which indicate that structure also served as a cookroom and tavern.

Resident Fishery

The lifestyle of fishers remained largely unchanged until the migratory fishery gave way to a resident industry in the early 1800s. The number of permanent settlers at Newfoundland and Labrador gradually increased during the 17th and 18th centuries for a variety of reasons. Planters and merchants hired caretakers to overwinter on the island and guard fishing gear; wars sometimes made it difficult for people to cross the Atlantic and return home; and the emergence of proprietary colonies in the 1600s helped create a foundation for permanent settlement. The Irish and English women who began to come to Newfoundland and Labrador in greater numbers during the 1700s, often to work as servants for resident planters, were crucial to settlement. Many married migratory fishers or male servants and settled on the island to raise families.The Napoleonic and Anglo-American wars of the early 1800s also did much to turn Newfoundland and Labrador's inshore fishery into a resident industry. As the French and American fisheries declined between 1804 and 1815, Newfoundland and Labrador cod became more valuable on the international market. This prompted many English and Irish fishers to permanently settle on the island instead of traveling there each summer to fish.

Instead of the large-scale fishing operations of the migratory fishery, which were directed by merchants and involved sizeable boat and shore crews, smaller household operations, largely relying on family labour, underpinned the resident fishery. Women and children assumed much of the work formerly done by headers, splitters, and salters, while men and older boys harvested cod. Fishers continued to use handlines throughout the 1800s, although some used more efficient gear, including cod seines, trawl lines, gillnets, and cod traps.

Otherwise, the nature of the inshore fishery remained largely unchanged. Fishers left their coastal homes early each morning to row or sail to nearby fishing grounds and returned when their boats were filled with cod. The shore crew split, salted, and dried the fish. One day each week was also devoted to catching bait – usually squid and capelin. As in the migratory fishery, fishing people traded their catch to merchants for food and supplies, or for credit in the merchant's stores. Instead of dealing with West Country firms, many 19th-century fishers worked for merchants based in Newfoundland and Labrador.

Some resident fishers also participated in the Labrador and bank fisheries. The former grew in popularity when some of the island's inshore cod stocks showed signs of depletion after 1815, prompting fishers to migrate to Labrador each summer and fish there. The Labrador fishery consisted of two groups: stationers and floaters. Islanders who set up living quarters on shore and fished each day in small boats were known as stationers, while floaters lived on board their vessels and sailed up and down the Labrador coast, often journeying further north than stationers.

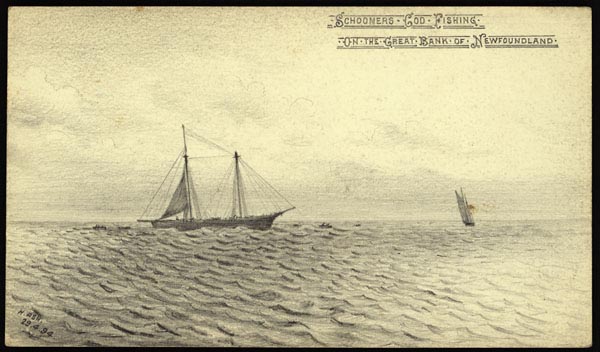

Schooners on the Grand Banks, 1894

Newfoundland and Labrador residents were engaged in the offshore banks fishery by the 1860s.

Pencil drawing by Henry Ash. “Schooners cod fishing on

the Great Bank of Newfoundland.” Courtesy of Library and Archives Canada

(00056).

Other Activities

To support themselves and their families throughout the year, many resident fishing people engaged in a wide range of economic activities during the 19th century. These included hunting game and trapping furs in the fall and winter; woodcutting in the winter; sealing in the winter and spring; and fishing, farming, and berry picking in the spring, summer, and early fall. Many families spent the warmer months near the shore to harvest fish and other coastal resources, before moving further inland during the fall and winter to cut timber and hunt game. Private vegetable gardens were also common in many rural communities. Most households grew crops that were easy to care for, preserved well, and were compatible with Newfoundland and Labrador's poor soil and cold climate. Cabbages were popular, alongside a variety of root vegetables, including potatoes, turnip, carrots, parsnip, beets, and onions.Better-developed social and political services also emerged during the 1800s to support a growing resident population. By the end of the century, many fishing people and their families had access to schools, doctors, nurses, churches and other services. The colony acquired much greater political autonomy, with the inauguration of Representative Government in 1832 and Responsible Government in 1855, and supported its own print media after 1807. Better modes of communication and transportation – including steamers, the railway, and the telegraph – also connected the Newfoundland and Labrador people to each other and the rest of the world on an unprecedented scale.

Version française

Video: A Settler's Life in Newfoundland and Labrador 1780-1840

Related Subjects

A Settler's Life in Newfoundland and Labrador 1780-1840

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5bU1hWWDnSY

-------------------

Colonization and Settlement: 1600-1830

The Early Settling of Newfoundland

European fishermen were lured by the fishery to Newfoundland since the beginning

of the sixteenth century. Yet their presence was required only for a few

months of the year; the fishing population was a migratory or seasonal one, returning to

homelands in Europe at the end of each fishing season. It was therefore a

standard assumption among historians that attempts to colonize the island early

in the seventeenth century were not successful, and that a resident population

emerged only in the late sevententh century. The seemingly slow rate of growth

and development was explained by historians as a consequence of a fundamental

hostility between the needs of a migratory fisherman for free access to beaches

and shore resources and the needs of the settler for permanent occupation of

property. Reinforcing this argument was the claim that the state persistently

declared settlement to be forbidden and attempted to prevent permanent

settlement in favour of a purely seasonal fishery based on a migratory labour

force. Only recently has this “illegal settlement” paradigm been recognized as

an historical myth and displaced by a recognition that the growth of a permanent

population in Newfoundland not only began much earlier than the late seventeenth

century but was always intimately linked to the fishery. Indeed, permanent

settlement had its greatest success wherever merchants and traders had

established themselves. enth and early eighteenth century. In this regard, a very useful essay to

examine is “Historical Fence-building: a critique of the historiography of

Newfoundland,” Newfoundland Quarterly LXXIV (Spring 1978): 21-30 by Keith

Matthews; it has since been reprinted with annotations and corrections in

Newfoundland Studies XVII: 2 (Fall 2001): 143-165.

Peter Pope has since developed sophisticated arguments which convincingly link

the fishery and settlement. Basically, Newfoundland reversed the usual pattern

in the early history of North America. Where mainland colonies were shaped by an

abundance of land and a shortage of labour, the Newfoundland fisheries had no

shortage of labour but strong competition for limited beach space needed to

"make" or cure fish. This led to strategies that encouraged over-wintering and

concentration by Europeans from the same home districts.

Pope developed these

arguments in a number of articles.

See for example "The European Occupation of Southeast Newfoundland:

Archaeological Perspectives on Competition for Fishing Rooms, 1530-1680," in

Christian Roy, Jean Bélisle,

Marc-André Bernier, and Brad Loewen (eds.), ArchéoLogiques; Collection Hors-Série

1. Mer et Monde: Questions d’archéologie maritime (Québec: Association des

archéologiques du Québec,

2003), pp. 122-133; and "Transformation of the Maritime Cultural Landscape of

Atlantic Canada by Migratory European Fishermen, 1500-1800," in Louis Sicking

and Darlene Abreu-Ferreira (eds.), Beyond the Catch: Fisheries of the North

Atlantic, the North Sea and the Baltic, 900-1850 (The Hague: Brill, 2008),

123-154. More recently, Pope suggests that innovations in the material culture

of ordinary European families appear to have played a critical role in the

transition from sixteenth-century seasonal European installations in North

America and the flurry of permanent settlements in the early seventeenth

century; see “The Consumer Revolution of the Late 16th Century and the European

Domestication of North America,” in Peter E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon

Lewis-Simpson, Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience

and Permanence in New Found Lands (Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY:

Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 37-47. Finally, in “The English and

the Irish in Newfoundland: Historical Archaeology and the Myth of Illegal

Settlement,” in Audrey Horning and Nick Brannon (eds.), Ireland and Britain

in the Atlantic World (Dublin: Wordwell Books, 2009), pp. 217-234, Pope

makes a compelling case which explains how substantial archaeological evidence

compiled in recent decades supports the conclusion that in Newfoundland, a

European presence can be detected as far back as the temporary cabins installed

by the sixteenth-century migratory fishery, followed by the establishment of a

number of permanent communities at various moments in the seventeenth century.

Though considerable attention continues to be given to proprietary, corporate,

and state colonies such as Ferryland, Cupid’s, and Placentia, the fact is that

much of the population growth of the seventeenth-century Newfoundland was a

consequence of informal settlement. By 1677, there were close to 2,000 people

living on the English Shore alone, with many more in French parts of the island.

In short, the notion that settlement was always held to be illegal, or that the

fishery was a determined foe of settlement, has been thoroughly discredited,

although the power of those myths remains persistent, so that our emerging

understanding of Newfoundland’s Early Modern settlement history still seems to

come as something of a surprise to many Newfoundlanders today.

Pope

brings many of his ideas and arguments on the early settlement of Newfoundland

together in

Fish Into Wine: The

Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University

of North Carolina Press, 2004). Here he shows that the proprietary and

corporate colonies of the early seventeenth century were more successful than

hitherto suspected at establishing permanent settlement in Newfoundland (see

below), and that the rate of growth was in fact not significantly worse than it

was for other European colonies in the region, such as Acadia. Indeed, it has

been argued that if we limit our assessment of settlement just to that coastal

strip known as “the English Shore,” then the density of occupation of usable

land by the early eighteenth century may in fact have been very high, and quite

comparable or even greater than elsewhere in English North America; see Andrew

Rolfson, Land

Tenure, Landowners, and Servitude on the Early-Eighteenth Century English Shore

(M.A. research paper, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2004).

Yet the

perception that early settlers lived lives of desperation and hardship, and that

Newfoundland was "a wild place largely unsuited for civilised activity,"

persists. The quotation comes from an article by David N. Collins, "Foe, Friend

and Fragility: Evolving Settler Interactions with the Newfoundland Wilderness,"

which appeared in the British Journal of Canadian Studies XXI: 1 (2008), pp. 35-62.

Collins endorses Gillian Cell’s view that the years of colonization efforts

between 1610 and the 1630s were "years of disillusionment." Significantly, none

of Peter Pope’s publications appear in the list of references used by Collins.

This is not to deny (as we shall see below) that settlement in Newfoundland was

difficult, only that the traditional perception that colonization was unfruitful

must be overturned. Certainly the fragility of indigenous populations, together

with the experience of English and French colonists, to which we can also add

the difficulties experienced in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries in

diversifying the economy, have collectively fostered a stronger appreciation for

limiting factors related to environmental conditions.

Yet scholarly interest into the relationship between the

human history of Newfoundland and environmental conditions is only now beginning

to attract focussed attention. One example of the way in which human habitation

has affected the natural environment is a recent study by Joyce Brown

Macpherson, “The Vegetational History of St. John’s,” in Alan G. Macpherson

(ed.), Four Centuries and the City: Perspectives on the Historical Geography

of St. John’s (St. John’s: Department of Geography, Memorial University of

Newfoundland, 2005), pp. 19-36. However, it is more typically the effect of the

natural environment on human habitation and activities in the fishery and trade

that attracts the attention of historians.

Towards this end, and the better to understand the several attempts to colonize Newfoundland in the seventeenth century, it would probably be wise to begin with some readings that provide insight into the motivations and assumptions underpinning overseas European colonization efforts generally, and more specifically, European perceptions of the opportunities that Newfoundland seemed to offer in particular. Closely related to this, we should also understand the way in which Newfoundland’s climatic and physical attributes were perceived. Begin with Humanism and America: An Intellectual History of English Colonisation, 1500-1625 (London & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), in which Andrew Fitzmaurice explores the motivations and inspirations behind English expansion and the idea of overseas colonization in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, including Newfoundland. Though he discusses such traditional themes as the motivations of wealth and profit, honour and glory, he also examines the nature of and possibilities for liberty, and the problems of just title. Follow this with David Quinn’s essay, “Newfoundland in the Consciousness of Europe in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries,” in George M. Story (ed.), Early European Settlement and Exploitation in Atlantic Canada (St. John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1982), pp. 9-30, as well as Mary C. Fuller’s essay, “Images of English Origins in Newfoundland and Roanoke,” in Germaine Warkentin and Carolyn Podruchny (eds.), Decentring the Renaissance: Canada and Europe in Multidisciplinary Perspective, 1500-1700 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), pp. 141-158. Then turn to the essay by Karen Ordahl Kupperman, "Fear of Hot Climates in the Anglo-American Colonial Experience," William & Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XLI: 2(April 1984), pp. 213-40 (see especially pp. 213-217). While Kupperman does not concentrate specifically on Newfoundland, her discussion is extremely useful in explaining why Europeans were so confident that Newfoundland was a sensible place to colonize. Another essay that is very useful in providing the background for early seventeenth century colonization efforts is Carole Shammas, "English Commercial Development and American Colonization 1560-1620," in K.R. Andrews, N.P. Canny, and P.E.H. Hair (eds.), The Westward Enterprise, English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic and America, 1480-1650 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1979), pp. 151-174.

Towards this end, and the better to understand the several attempts to colonize Newfoundland in the seventeenth century, it would probably be wise to begin with some readings that provide insight into the motivations and assumptions underpinning overseas European colonization efforts generally, and more specifically, European perceptions of the opportunities that Newfoundland seemed to offer in particular. Closely related to this, we should also understand the way in which Newfoundland’s climatic and physical attributes were perceived. Begin with Humanism and America: An Intellectual History of English Colonisation, 1500-1625 (London & New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003), in which Andrew Fitzmaurice explores the motivations and inspirations behind English expansion and the idea of overseas colonization in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, including Newfoundland. Though he discusses such traditional themes as the motivations of wealth and profit, honour and glory, he also examines the nature of and possibilities for liberty, and the problems of just title. Follow this with David Quinn’s essay, “Newfoundland in the Consciousness of Europe in the Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries,” in George M. Story (ed.), Early European Settlement and Exploitation in Atlantic Canada (St. John’s: Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1982), pp. 9-30, as well as Mary C. Fuller’s essay, “Images of English Origins in Newfoundland and Roanoke,” in Germaine Warkentin and Carolyn Podruchny (eds.), Decentring the Renaissance: Canada and Europe in Multidisciplinary Perspective, 1500-1700 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), pp. 141-158. Then turn to the essay by Karen Ordahl Kupperman, "Fear of Hot Climates in the Anglo-American Colonial Experience," William & Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XLI: 2(April 1984), pp. 213-40 (see especially pp. 213-217). While Kupperman does not concentrate specifically on Newfoundland, her discussion is extremely useful in explaining why Europeans were so confident that Newfoundland was a sensible place to colonize. Another essay that is very useful in providing the background for early seventeenth century colonization efforts is Carole Shammas, "English Commercial Development and American Colonization 1560-1620," in K.R. Andrews, N.P. Canny, and P.E.H. Hair (eds.), The Westward Enterprise, English Activities in Ireland, the Atlantic and America, 1480-1650 (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1979), pp. 151-174.

Newfoundland did not, of course,

measure up to the overly optimistic expectations and predictions of early

promoters of colonization. The thin soil, short growing season, lack of

diversity in local flora and fauna, climatic extremes and other environmental

factors would impair colonization and vigorous settlement growth for well over

a century. The survival of the first colonists depended very much on reliable

yet not always adequate trans-Atlantic shipments of essential supplies of gear,

clothing, and above all food. As Paula Marcoux explains in “Bread and

Permanence,” bread was the most essential of common foods of Europeans in the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, yet it represented not only sustenance but

a tangible reminder in their new environments of home. As a result, they went to

considerable effort to supply themselves with bread. Her essay appears in Peter

E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon Lewis-Simpson, Exploring Atlantic Transitions:

Archaeologies of Transience and Permanence in New Found Lands (Woodbridge,

Suffolk and Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 48-56. Yet provisions from

home had to be preserved in order to survive the journey without spoiling, and

this often meant that the very nourishment on which the colonists depended for

survival could also be fatally deficient nutritionally. The persistence of scurvy in the experience of the first colonists

was a sobering reminder of the conflict between expectations and the reality of

Newfoundland as a venue for successful settlement. J.K. Crellin looks at the

problem of scurvy and the the measures used by early colonists to combat it in

“Early Settlements in Newfoundland and the Scourge of Scurvy,” Canadian

Bulletin of Medical History XVII: 1-2 (2000), pp. 127-136; Crellin develops

the theme further in A Social History of Medicines in the Twentieth Century:

To Be Taken Three Times a Day (New York and London: Pharmaceutical Products

Press, 2004). More recently,

Steven R. Pendery and Hannah E.C. Koon apply new kinds of evidence –

particularly archaeological evidence – to determine the degree to which vitamin

deficiencies in early settlements aggravated other challenges of early

colonization; see “Scurvy’s Impact on European Colonization in Northeastern

North America,” in Peter E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon Lewis-Simpson,

Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience and Permanence in

New Found Lands (Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY: Boydell Press,

2013), pp. 57-65.

The first efforts to colonize Newfoundland occurred

early in the seventeenth century, but the idea of establishing permanent

settlements on the island had already been promoted for several decades by then.

Some late sixteenth century promotional literature appears in David Quinn (ed.),

New American World; A Documentary History of North America to 1612. Volume

III: Plans for North America. The Roanoke Voyages. New England Ventures (New

York: Arno Press, 1979), but it is the fourth volume of this documentary

compilation, Newfoundland – From Fishery to Colony; Northwest Passage

Searches, that contains the richest sampling of documentation, including

much of that associated with Humphrey Gilbert's voyage of 1583 which led to his

formal claim of Newfoundland on behalf of Elizabeth I as well as material

related to the first colonization venture at Cupid's Cove in 1610. An earlier

collection of documentation edited by David Quinn and published in two volumes

by the Hakluyt Society in 1940 is The Voyages and Colonising Enterprises of

Sir Humphrey Gilbert, which has since been reprinted (New York: Kraus,

1967). David Quinn also wrote a superb booklet for the Newfoundland Historical

Society, Sir Humphrey Gilbert and Newfoundland (St. John's: Newfoundland

Historical Society, 1983) which places Gilbert clearly in his English and North

Atlantic social context; this essay has been reprinted in a collection of

Quinn's writings, Explorers and Colonies: America, 1500-1625 (London &

Ronceverte, WV: Hambledon Press, 1990), pp. 207-24. As well, Quinn wrote the

essay on Gilbert that appears in the

DCB, I: 331-336.

Though it had no immediate significance in terms of

advancing the settlement of Newfoundland, the Gilbert voyage, together with

Cabot’s discovery, did add weight to an emerging notion of overseas empire and

particularly the belief that not only discovery but also effective occupation

were critical to subsequent British claims to sovereignty over Newfoundland;

see, for instance, Ken MacMillan, “Discourse on History, Geography, and Law:

John Dee and the Limits of the British Empire, 1576-80,” Canadian Journal of

History XXXVI: 1 (April 2001), 1-25. MacMillan maintains that, on the eve of

Humphrey Gilbert’s famous voyage of 1583, Dee helped define the principles by

which sovereignty over overseas territories such as Newfoundland would be

asserted, and thereby challenging Spanish and Portuguese claims that were still

based in part on papal pronouncements. On the other hand, in "Taking Possession

and Reading Texts: Establishing the Authority of Overseas Empires," William

and Mary Quarterly, 3rd ser., XLIX, No. 2 (April 1992), 183-209, Patricia

Seed sees strong similarities between the way in which the Spanish and

Portuguese asserted claims to overseas territories and the way in which the

English subsequently asserted their own claims. A key element in Seed’s analysis

is Sir Humphrey Gilbert’s ceremony in St. John’s harbour. While she incorrectly

identifies Gilbert’s presence there as “the first English effort at New World

settlement” (a not uncommon mistake), her analysis is very useful for the way in

which it explores the basis on which Europeans claimed overseas lands not

possessed by another Christian monarch. Finally, for insight into the way in

which discoveries and claims made in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries could

continue to provide the basis for diplomatic assertions of sovereignty in later

centuries, see Vera Lee Brown, "Spanish Claims to a Share in the Newfoundland

Fisheries in the Eighteenth Century," Canadian Historical Association Annual

Report, 1925, pp. 64-82.

Colonization Attempts in the Seventeenth Century

The first determined attempt at colonization occurred in 1610 at Cupid's Cove

under the leadership of John Guy on behalf of the London and Bristol Company or, more

commonly, the Newfoundland Company. Apart from the aforementioned documentary collection

edited by Quinn, the best work to date on this enterprise is Gillian Cell (ed.), Newfoundland

Discovered: English Attempts at Colonization, 1610-1630 (London: Hakluyt Society,

1982; 2nd series, #180). Cell's "Introduction" is thorough, and revises to some

extent the conclusions she drew in her earlier work, English Enterprise at Newfoundland

1577-1660 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1969). Should these works not be

available, one might consult Cell's essay, "The Cupid's Cove Settlement: A Case Study

of the Problems of Colonization," in George M. Story (ed.), Early European

Settlement and Exploitation in Atlantic Canada (St. John's: Memorial University of

Newfoundland, 1982), pp. 97-114. Another of Cell's essays, "The Newfoundland Company:

A Study of Subscribers to a Colonizing Venture," The William & Mary Quarterly,

3rd ser., XXII(1965): 611-25, places the first attempt to colonize Newfoundland within its

English social and economic context. The essay was reprinted in the first edition of J.M.

Bumsted (ed.), Canadian History Before Confederation (Georgetown:

Irwin-Dorsey, 1972), pp. 43-57.

The late Alan F. Williams prepared

a full biographical treatment of John Guy, but it was not finished before

Williams died. Now, the manuscript has been edited for publication by W. Gordon

Handcock and Chesley W. Sanger and published as John Guy of Bristol and

Newfoundland: His Life, Times and Legacy (St. John’s, NL: Flanker Press, 2011).

The first volume of the

DCB also contains useful profiles of

John

Guy, the pirate

Peter Easton, and several of the Cupid's Cove colonists.

What we thought we knew about the Cupids settlement from the historical record

has been significantly enhanced since 1995 by the intensive and continuing

archaeological work of William Gilbert and his team, supported by the Baccalieu

Trail Heritage Corporation. Much of this work is described

on-line, though Gilbert’s work has also found its way into more traditional

print essays. For example, he was already suggesting as early as 1996 that there

was is still much to be learned about this first attempt to establish a colony

in Newfoundland; see "Looking for Cupers Cove: Initial Archaeological Survey

and Excavations at Cupids, Newfoundland," Avalon Chronicles I (1996): 67-95,

together with an update, “Finding Cupers Cove: Archaeology at Cupid’s,

Newfoundland until 1696,” Avalon Chronicles VIII (2003), Special Issue,

“The English in America 1497-1696,” pp. 117-184.

The significance of the archaeological work at Cupids cannot be overstated. This

first settlement in Newfoundland had been cited by historians from Prowse to

Cell as the outstanding example of a seemingly well-conceived attempt at

settlement which quickly failed. The archaeology confirms a different story, for

the site was permanently occupied throughout most of the seventeenth century.

William Gilbert summarizes what we now know in “`Dwelling there still':

Historical Archaeology at Cupids and Changing Perspectives on Early Modern

Newfoundland,” in Peter E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon Lewis-Simpson, Exploring

Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience and Permanence in New Found

Lands (Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2013), pp.

215-223.

Gilbert has also written about Guy's efforts to explore the region and his encounter with

the Beothuk Indians; see "‘Divers Places': The Beothuk Indians and John Guy's

Voyage into Trinity Bay in 1612," Newfoundland Studies VI: 2 (Fall 1990):

147-67. To this point, that encounter has interested historians largely because it is one

of the earliest, detailed descriptions by Europeans of Newfoundland's indigenous people.

Recently, however, Peter Pope has offered the provocative argument that Beothuk pilfering

of iron goods from European fishing camps may have served as an inducement for European

settlement; see Peter E. Pope, "Scavengers and Caretakers: Beothuk/European

Settlement Dynamics in Seventeenth-Century Newfoundland," Newfoundland Studies

X: 2 (Fall 1993): 279-293.

Apart from the Cupid's Cove venture, most other English

colonization efforts have received uneven treatment. William Vaughan's attempt

to establish a colony at Renews is briefly described in Cell's essay on

Vaughan in the

DCB,

I: 654-656 and in her collection of documents, Newfoundland Discovered.

More recently, Anne Lake Prescott focuses upon Vaughan’s colonization efforts in

order to examine how Newfoundland was perceived by Europeans at this time; see

"Relocating Terra Firma: William Vaughan’s Newfoundland," in Germaine Warkentin

and Carolyn Podruchny (eds.), Decentring the Renaissance: Canada and Europe

in Multidisciplinary Perspective, 1500-1700 (Toronto: University of Toronto

Press, 2001), pp. 125-140. As the editors of this intriguing volume explain in

their Introduction, Prescott examines "the mental universe of the English poet

and essayist William Vaughan, who, though he probably never visited

Newfoundland, was certain he could write with authority about it." Inhabitancy

would persist at Renews; this is supported both by the documentary record and

increasingly by archaeological work – see, for instance, F.N.L. Poynter (ed.), The Journal of

James Yonge (1647-1721) Plymouth Surgeon (Bristol, 1963), as well as Stephen F. Mills,

"The House that Yonge Drew? An Example of Seventeenth-Century Vernacular Housing in

Renews," Avalon Chronicles I (1996): 43-66. Nevertheless, Vaughan's

colonization effort was quickly abandoned, though the experience was not without

significance. In a vain attempt to administer and reorganize his colony in 1618, Vaughan

appointed Richard Whitbourne, whose essay, "A Discourse and Discovery of

New-Found-Land," published in 1620, revised in 1622 and reprinted in both of the

document collections which have been edited by Cell and Quinn, has been an important

source of information on Newfoundland's fishery and the settlement efforts at this time.

Whitbourne's connection with the Renewse settlement continued after Lord Falkland took

over the enterprise around 1620. The most thorough discussion of the Renews colony is that

provided in Cell's Newfoundland Discovered;

Whitbourne and

Sir Francis Tanfield

(whom Falkland appointed as governor) both appear in essays by Cell in the

DCB, I:

668-669 and 632.

The exception to the cursory treatment usually accorded these

early colonization efforts is the colony at Ferryland,

which

was established by

George Calvert (later Lord Baltimore) after he purchased a

tract of land from William Vaughan. After several years of efforts and

considerable investment which was not rewarded with the kind of results Calvert

wanted, he gave up on the colony, which was then taken over by David Kirke.

Calvert’s

role in the history of Ferryland, his subsequent role in setting into motion the

founding of Maryland in what is now the United States, together with a fairly

rich manuscript legacy, has meant that Calvert has attracted a greater degree of

academic attention than almost any other individual associated with the early

attempts to colonize Newfoundland. Moreover, the tradition of

manuscript research has recently been enhanced by extensive archaeological excavations on

the Ferryland site. Peter Pope brought both the historian’s skills and those of the

archaeologist to bear on the Ferryland experience in his award-winning dissertation, The

South Avalon Planters, 1630 to 1700: Residence, Labour, Demand and Exchange in

Seventeenth-century Newfoundland (PhD thesis, Memorial University of

Newfoundland, 1992). That dissertation , together with more than a decade’s

additional research, would be transformed into Fish Into Wine: The

Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel Hill: University

of North Carolina Press, 2004), Pope’s definitive monograph on the relationship

between English settlement, the fishery, and the exchange of fish for Iberian

wine during the seventeenth century. This seminal work not only challenges much

of the persistent received wisdom about the early fishery, trade and settlement

in Newfoundland but lays it permanently (one hopes!) to rest. The book should

become essential reading for every student in early modern Newfoundland history.

For students engaged

in research into the Ferryland colony, there is considerable documentary

material in print. Much of this material was compiled in Gillian Cell’s

Newfoundland Discovered as well as her earlier English Enterprise. To

this, we can add "Six Letters from the Early Colony of Avalon" which Peter Pope

contributed to Avalon Chronicles I (1996): 1-20. A recent addition to the

documentary legacy is "Edward Wynne’s The Brittish India or A Compendious

Discourse tending to Advancement (circa 1630-1631)," with an extensive

introduction by Barry C. Gaulton and Aaron F. Miller, together with a

transcription of Wynne’s essay. Wynne was Calvert’s governor at Ferryland from

1621 to 1625 (a brief biography of

Wynne by Gillian Cell appears in

the

DCB,

Vol. I, p. 672), and his essay used that experience to promote overseas English

colonization. The document is featured in Newfoundland and Labrador Studies

XXIV: 1 (Spring 2009): 111-137.

Insight into the

Calvert family itself is possible through a substantial literature. It is

unlikely that much can be added to what Peter Pope has to say in his

aforementioned book, Fish Into Wine. Still, the MA dissertation by James

Edward Prindeville, The Calvert Family Claims to the Colony of Avalon in

Newfoundland 1623-1754 (MA thesis, Catholic University of America,

Washington DC, 1949), remains useful, though a more modern and comprehensive

study – one that examines the family both before, during and after its

Newfoundland experience – is now available to students in English and

Catholic: The Lords Baltimore in the Seventeenth Century by John D. Krugler

(Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004). In “The Lords Baltimore

in Ireland,” James Lyttleton looks at the experience of the Lords Baltimore in

Ireland, and the degree to which this conditioned their experiences in

Newfoundland. The essay appears in Peter E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon

Lewis-Simpson, Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience

and Permanence in New Found Lands (Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY:

Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 259-269.

There are as well a

number of essays and articles in print on Calvert’s Ferryland colony. For many

years, the standard overview of the colony was provided by Thomas Coakley in

"George Calvert and Newfoundland: ‘The Sad Face of Winter’," Maryland

Historical Magazine LXXI: 1 (Spring 1976): 1-18. Coakley explained Calvert’s

decision to withdraw from the colony in terms of the difficult environmental

challenge facing the colonists in Newfoundland. Thus, Coakley reinforced the

prevailing view that the colony struggled, a view which Pope and others have

gone far to amend. See for instance “Ferryland’s First Settlers (and a Dog

Story)” by James A. Tuck, which surveys Calvert’s tenure in Ferryland between

1621 and 1629. While Tuck concedes that “weather has traditionally been seen as

the reason for Calvert’s departure..., other factors may have precipitated his

move to the Chesapeake in 1629.” The essay appears in Peter E. Pope (ed.), with

Shannon Lewis-Simpson, Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of

Transience and Permanence in New Found Lands (Woodbridge, Suffolk and

Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 270-277. See also

what conclusions can be drawn from comparative archaeology by looking at Aaron

F. Miller, Avalon and Maryland: A Comparative Historical Archaeology of the

Seventeenth-Century New World Provinces of the Lords Baltimore (1621–1644)

(PhD thesis. Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2013).

Calvert was also

quite sympathetic to Roman Catholicism at a time when Catholics in England faced

discrimination and growing persecution; Calvert would eventually convert to

Catholicism. This has long raised questions whether Calvert was motivated into

sponsoring a colony in Newfoundland out of a desire to create a religious haven

for Catholics. Coakley makes clear that this was not the case, but the Catholic

connection continues to attract interest. Raymond Lahey explores this element in

"The Role of Religion in Lord Baltimore's Colonial Enterprise," Maryland

Historical Magazine LXXII: 4(Winter 1977): 492-511 as well as in "Avalon:

Lord Baltimore's Colony in Newfoundland," in George M. Story (ed.), Early

European Settlement and Exploitation in Atlantic Canada (St. John's:

Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1982), pp. 115-138. However, Lahey

recognizes that the evidence is only suggestive and still favours Coakley's

conclusion. More recently, Luca Codignola has turned to documents in the Papal

Archives in the Vatican to expand upon the connection between the Ferryland

colony and Catholicism; his research, based on a selection of documents which he

presents in The Coldest Harbour of the Land; Simon Stock and Lord Baltimore's

Colony in Newfoundland, 1621-1649 (Montreal: McGill-Queen's University

Press, 1988; trans. Anita Weston), does not significantly alter the conclusions

of Coakley and Cell.

Although Allan

Fraser’s essay on

George Calvert

in the

DCB,

I:

162-3 concludes that Calvert had no

lasting influence on Newfoundland, this too is an assessment that is being

revised thanks to recent historical and archaeological scholarship. The

substantial archaeological work undertaken at Ferryland over the past decade to

which reference has already been made has led not only to a substantial

reassessment in its own right of the history of the colony but has also

encouraged renewed interest in the documentary history of the colony. One very

tangible benefit of this attention has been the creation of the "Colony of

Avalon Foundation" which began publishing Avalon Chronicles, an annual yearbook

of scholarly research concerning not only the Ferryland experience but "the

early colonial history and archaeology of eastern North America" as well. Thus,

the first volume includes not only essays on Ferryland but on Cupid’s Cove and

Renews as well (see elsewhere for specific references).

The archaeological work at Ferryland has been directed by Memorial

University of Newfoundland's James Tuck, who describes both the archaeology itself and the

history of archaeology at Ferryland in "Archaeology at Ferryland, Newfoundland,"

Newfoundland Studies X: 2(Fall 1993): 294-310, "Archaeology at Ferryland,

Newfoundland 1936-1995," Avalon Chronicles I (1996): 21-41, and

(co-authored with Barry Gaulton) “The Archaeology of Ferryland, Newfoundland

until 1696,” Avalon Chronicles VIII (2003), Special Issue, “The English

in America 1497-1696,” pp. 187-224. This work is not

yet complete,

but already it has

provided us with a much richer appreciation of everyday life in

seventeenth-century Newfoundland. See for example Lisa M. Hodgetts, "Feast or

Famine? Seventeenth-Century English Colonial Diet at Ferryland, Newfoundland,"

Historical Archaeology XL: 4 (Winter 2006), 125-138. More to the point,

all this work confirms that Ferryland, in contrast to past perceptions of early

Newfoundland colonization ventures, should not be regarded as a "failure."

Together with the archaeological work being done at Cupid’s on John Guy’s

settlement, this forces us to rethink our understanding of the history of

seventeenth-century Newfoundland.

After Calvert’s departure,

David Kirke took Ferryland over and quickly clashed with the seasonal fishermen.

Eventually, Kirke was made to return to England to answer charges of

interference with the fishery, and this has long provided much ammunition for

those who argued that the growth of Newfoundland settlement was impaired by an

unremitting hostility between the fishing interests and the settlers. See for

example John Moir’s discussion of Kirke’s tenure at Ferryland in his essay on

Kirke

in the

DCB,

I: 404-407. While such a conclusion still cannot be ruled out entirely, it is

also evident that the real story is much more complicated than that. For

instance, due to the work of Tuck, Pope, and others, there has been growing

interest in the ability of the Kirke family to thrive in a place in which the

Calvert family had invested a great deal and yet, in

the end, abandoned. Reinforcing the conclusions Peter Pope

reached in his monograph, Barry Gaulton attributes the Kirke success to

their ability to modify the Calvert infrastructure at Ferryland

and develop a plantation based on merchandising and

fishing; see “The Commercial Development of Newfoundland's English Shore: The

Kirke Family at Ferryland, 1638-96,” in Peter E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon

Lewis-Simpson, Exploring Atlantic Transitions: Archaeologies of Transience

and Permanence in New Found Lands (Woodbridge, Suffolk and Rochester, NY:

Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 278-286. It is certainly clear that the findings of

the archaeological teams at Ferryland and at Cupid’s, together with the

comprehensive reexamination of the manuscript record by Peter Pope in his

doctoral dissertation and numerous articles provide a striking demonstration of

the way in which the revision of Newfoundland history is both vigorous and

persistent.

That revision

affects not only the English attempts at colonization in seventeenth-century

Newfoundland but also French efforts. An important element in the process of

revision is provided by the useful comparisons that can be made between the

English experience at colonizing Newfoundland with that of the French. The

French colony of Plaisance (Placentia, as it was known to the English), was

founded in 1662. For the longest time, the best available work in English on the

French colonial experience in Newfoundland was F.B. Briffett, A History of

the French in Newfoundland Previous to 1714 (MA thesis, Queen's University,

1927). Then came a number of studies emerging out of Parks Canada research into

the structural remains of the colony by John Humphreys, Jean-Pierre Proulx,

Frederick J. Thorpe and others. For many years, one of the better overviews of

Plaisance was the brief survey by John Humphreys; see Plaisance: Problems of

Settlement at this Newfoundland Outpost of New France 1660-1690 (Ottawa:

National Museums of Canada, 1970). But Humphreys also endorsed the notion that

Plaisance was a colony which struggled against several handicaps, and that its

growth was therefore impaired, with the result that the French Crown gave up on

Plaisance and turned it over to the British in 1714. In short, historians of

Plaisance, like those who studied the English colonies of the first half of the

seventeenth century, concluded that the colonization of Newfoundland was not a

success.

As evidence of this

"failed colony" paradigm, historians pointed to the several censuses compiled by

the authorities; these were assembled and published by Fernand-D. Thibodeau as "Recensements

de Terreneuve et Plaisance" in Mémoires

de la Société Généologique Canadienne-Française X: 3-4 (juillet-octobre

1959), 179-88, XI: 1-2 (janvier-avril 1960), 69-85, XIII: 10 (octobre 1962):

204-8, and XIII: 12 (décembre 1962), 244-55. These seemed to confirm that the

French colony suffered from mediocre growth. A "snapshot" of Plaisance in the

mid-1690s is also provided by an anonymous and undated document found in the

French archives. Caroline Ménard has examined the document and suggests that it

was written by Claude-Charles Bacqueville de la Potherie (1663-1736), author of

Histoire de l’Amérique septentrionale (Paris, 1722); see "Documents: Un

mémoire écrit

par Bacqueville de la Potherie?," Newfoundland and Labrador Studies XXI:

2 (Fall 2006), 319-341. The unimpressive performance of the French colony has

been blamed on friction between metropolitan fishermen and resident fishermen,

while Humphreys blamed the seeming lack of growth on environmental factors which

prevented the settlement from developing a more robust and versatile economy,

and instead made it dependent on the fisheries.

But was the

performance of the French colony of Plaisance truly mediocre? In her PhD

dissertation, The Historical Archaeology of a French Fortification in the

Colony of Plaisance, the Vieux Fort Site (ChAl-04), Placentia, Newfoundland

(PhD thesis, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2012), Amanda Crompton points

out that Plaisance "never supported a very large population, but neither did

other Newfoundland settlements, nor did other settlements elsewhere in Acadia

and Maine," citing Peter Pope’s Fish Into Wine. The permanent population

could draw from the seasonal labour force to serve their labour needs, so this

also enabled the colony to thrive without a large resident population. Crompton

supports her conclusions with reference to work by Nicolas Landry, who offered

an analysis of the seemingly weak demographic performance of Plaisance in his

article "Peuplement d’une colonie de pLche

sous le régime français: Plaisance, 1671-1714," The Northern Mariner / Le

Marin du nord XI: 2 (April 2001): 19-37. Crompton also points out that a

number of permanent residents had spouses in other parts of the French Atlantic,

such as France. "Clearly, the notion of a permanently-resident family was not

limited to the presence of the nuclear family living in the colony. Indeed,

fishing colonies did not need continual population growth in order to be vital

places.... fishing colony populations are smaller than colonies elsewhere" (pp.

82-83). Students should also consult what is sure to become the definitive

treatment of the French colony, Plaisance, Terre-Neuve 1650-1713: Une colonie

française en Amérique

(Sillery, QC: Septentrion, 2008) by Nicolas Landry.

Nevertheless, in one

very important respect, Plaisance did not resemble the earlier English

attempts at colonization in Newfoundland. Unlike those English colonies,

Plaisance was a creation of the government. As Elizabeth Mancke succinctly

explains, "Plaisance ... functioned not so much as a colony – the nucleus of a

new society – but as a way for the French government to assert administrative

control, if not sovereignty, over the highly decentralized and dispersed

commercial spaces of the fishery." See Elizabeth Mancke, "Spaces of Power in the

Early Modern Northeast," in Stephen J. Hornsby and John G. Reid (eds.), New

England and the Maritime Provinces: Connections and Comparisons (Montreal &

Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2005), pp. 32-49, esp. p. 42; see

also Laurier Turgeon, "Colbert et la pêche

française à Terre-Neuve," in Roland Mousnier (directeur), Un Nouveau Colbert:

Actes du Colloque pour le tricentenaire de la mort de Colbert (Paris:

Editions Sedes, 1985), pp. 255-268. This meant that the French Crown invested a

great deal of human and financial capital in the colony – the fortifications,

the garrison, the administration. The fact that this enormous expenditure did

not apparently stimulate substantial growth at Plaisance has been used as

further evidence of the "failed colony" paradigm. Frederick J. Thorpe explores

this paradox in "Fish, Forts and Finance: The Politics of French Construction at

Placentia, 1699-1710," Canadian Historical Association Historical Papers 1971,

pp. 52-63, subsequently developing the theme more fully in his doctoral

dissertation, The Politics of French Public Construction in the Islands of

the Gulf of St. Laurent, 1695-1758 (PhD thesis, University of Ottawa, 1974).

See also Roland Plaze, La colonie Royale de Plaisance, 1689-1713: impact du

statut de colonie royale sur les structures administratives (MA thesis,

Université

de Moncton, 1991) as well as essays on the

Sieur de La Poippe and

Antoine Parat,

both of whom served as governors at Plaisance, in the

DCB,

I: 418-419, 530.

In

fairness, it would probably be more accurate to say that

the Crown was disappointed with the way in which the colony satisfied –

or not –

the role it was expected to play in the French mercantile empire of the

North

Atlantic. It certainly seems reasonable to conclude that the difficulty

of

finding a prosperous niche within the emerging French Atlantic led

merchants at

Plaisance to turn to commercial linkages outside that mercantilistic

framework. Thus, we know that Plaisance developed trade links with New

England –

see the biography of

David Basset in

the

DCB,

II, pp. 46-47. Basset was a Boston-based trader of Acadian Huguenot origins

who engaged in commerce between New England and Plaisance.

Amanda Crompton confirms that, while the little French colony might not have

been able to rely on supplies delivered by official ships, it could and did

develop commercial connections (indeed “a dependence”) on seasonal visits by

merchant ships from other parts of the Atlantic world. The archaeological record

reflects both the nature and the sources of necessary supplies as well as the

social contexts of this colonial-metropolitan trade; see Crompton’s essay, “Of

Obligation and Necessity: The Social Contexts of Trade between Permanent

Residents and Migratory Traders in Plaisance, Newfoundland (1662-90),” in Peter

E. Pope (ed.), with Shannon Lewis-Simpson, Exploring Atlantic Transitions:

Archaeologies of Transience and Permanence in New Found Lands (Woodbridge,

Suffolk and Rochester, NY: Boydell Press, 2013), pp. 245-255. Crompton also

provides us with a fascinating glimpse into the everyday material world of the

French soldiers who were stationed in Plaisance in “‘Deux mains pour la guerre

et la terre’: Soldiers in the French Colony of Plaisance, Newfoundland,

1662-1690,” in Scott Jamieson, Anne Pelta, Anne Thareau (eds.), Newfoundland

and Labrador Studies, Occasional Papers No. 3: The French Presence in

Newfoundland and Labrador: Past, Present, and Future (St. John’s: Memorial

University of Newfoundland, 2015), pp. 159-187.

The other

consequence of Plaisance’s role as a Crown colony was visible during the wars

fought between France and England during the life of the colony. Interest in the

military and naval function of Plaisance can be traced back to Grace Tomkinson,

"That Wasp’s Nest, Placentia," Dalhousie Review XIX (1939), 204-214. More

recent publications offer a more analytical approach to the strategic function

of Plaisance. See for example two essays which appeared n Yves Tremblay (ed.),

Canadian Military History Since the Seventeenth Century; Proceedings of the

Canadian Military History Conference, Ottawa, 5-9 May 2000 (Ottawa:

Directorate of History and Heritage, National Defence, 2001); Frederick J.

Thorpe contributed "French Strategic Ideas in the Defence of the Cod Fishery

1663-1713," pp. 41-47, and James Pritchard contributed "Canada and the Defence

of Newfoundland During The War of the Spanish Succession, 1702-1713," pp. 49-57.

In "‘Le Profit et La Gloire’: The French Navy’s Alliance With Private Enterprise

in the Defense of Newfoundland, 1691-1697," Newfoundland Studies XV: 2

(Fall 1999): 161-175, James Pritchard offers not only a fine study of the

defence of Plaisance in wartime, but also reveals the degree to which the French

state relied on private enterprise rather than its navy to maintain its presence

in Newfoundland. Nicolas Landry has turned his attention to Plaisance-based

privateering during the war immediately following, with particular attention to

its significance to the local economy; see "Portrait des activités

de course à Plaisance, Terre-Neuve, 1700-1715," Les Cahiers de la Société

historique acadienne XXXIII (1 et 2), 68-87, and "Les activités de course

dans un port colonial français: Plaisance, Terre-Neuve, durant la guerre de

Succession d’Espagne, 1702-1713," Acadiensis XXXIV: 1 (Autumn 2004):

56-79. Landry also explores the ingredients essential to the success of the

merchants of Plaisance in "‘Qu’il sera fait droit à qui il appartiendra’: la

société de Lasson-Daccarrette à Plaisance 1700-1715," Newfoundland Studies

XVII: 2 (Fall 2001): 220-256. Of course, these articles appeared before Landry’s

book, Plaisance, Terre-Neuve 1650-1713: Une colonie française en Amérique

(Sillery, QC: Septentrion, 2008) and students are encouraged to turn there

first.

Plaisance was not

the only place where French fishermen established settlement in Newfoundland. A

convenient overview of French settlement in other parts of Newfoundland is

presented by Olaf U. Janzen in "The French Presence in Southwestern and Western

Newfoundland Before 1815," in André

Magord (directeur), Les Franco-Terreneuviens de la péninsule de Port-au-Port:

Évolution d’une identité franco-canadienne (Moncton, New Brunswick: Chaire

d’études acadiennes, Université

de Moncton, 2002), pp. 29-49. Janzen develops the overview in order to provide

context for his examination of French settlement in the Port-aux-Basques and

Codroy area, a subject that he developed in such earlier publications as “‘Une

grande liaison’: French Fishermen from Ile Royale on the Coast of Southwestern

Newfoundland, 1714-1766 – A Preliminary Survey,” Newfoundland Studies

III: 2 (Fall, 1987): 183-200 and “‘Une petite Republique’ in Southwestern

Newfoundland: The Limits of Imperial Authority in a Remote Maritime

Environment,” in Research in Maritime History, Vol. 3: People of the

Northern Seas (St. John’s, NF: International Maritime Economic History

Association, 1992), ed. Lewis Fischer and Walter Minchinton, pp. 1-33, reprinted

in Olaf U. Janzen, War and Trade in Eighteenth-Century Newfoundland

(“Research in Maritime History,” No. 52; St. John’s, NL: International Maritime

Economic History Association, 2013), pp. 69-97. The vulnerability of this remote

French community in wartime was the focus of another of Janzen’s essays, “Un

Petit Dérangement: The Eviction of French Fishermen from Newfoundland in 1755,”

in Olaf U. Janzen, War and Trade in Eighteenth-Century Newfoundland

(“Research in Maritime History,” No. 52; St. John’s, NL: International Maritime

Economic History Association, 2013), pp. 119-128.

Before we leave the

topic of Plaisance, some words should be said about our understanding of the

society of the French fishermen who lived in Newfoundland. For the longest time,

we knew very little about the social life of the fisher folk of Plaisance and

the adjacent communities during the era of French settlement in Newfoundland.

This deficiency is ending, thanks in considerable measure to the efforts of

Nicolas Landry, who has used the post-mortem inventories of Plaisance to reveal

more about the material culture of the inhabitants of the lower social classes

of Plaisance. His findings appeared initially in several essays, including

"Transmission du patrimoine dans une colonie de pLche:

analyse préliminaire des inventaires après-décès à Plaisance au XVIIIe siècle,"

in A.J.B. Johnston (ed.), Essays in French Colonial History: Proceedings of

the 21st Annual Meeting of The French Colonial Historical Society (East

Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 1997), pp. 156-70; and "Culture

matérielle et niveaux de richesse chez les pêcheurs de Plaisance et de l’île

Royale, 1700-1758," Material History Review 48 (Fall 1998): 101-122.

Landry has also endeavoured to look comparatively at working conditions in three

separate fishing societies during the French regime, including Plaisance, Île

Royale and the Gaspé in "Pêcheurs et entrepreneurs dans le Golfe du

Saint-Laurent sous le régime français," Port Acadie: Revue interdisciplinaire

en études acadiennes, III (printemps/Spring 2002): 13-42. Nor has Landry

neglected the seasonal and migratory labourers in the French fishery; see

Nicolas Landry, "Pecheurs-engagés à Terre-Neuve sous le Régime français,

1688-1713," French Colonial History VIII (2007): 1-21.

Others have followed

in Landry’s footsteps. Damien Rouet, for example, has attempted to reconstruct

the society of Plaisance towards the end of the French period of control; see "Territoires,

identité

et colonisation: l’exemple de Plaisance," in Maurice Basque and Jacques-Paul

Couturier (eds.), Les Territoires de l’identité: perspectives acadiennes et

françaises, XVIIe-XXe siècles (Moncton: Université de Moncton, 2005), pp.

191-203. In Religious Life in French Newfoundland to 1714 (MA thesis,

Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1999) Victoria Taylor-Hood examines the

religious life of Plaisance. She suggests that the clergy who served the colony

– the secular clergy during its early years, then the Récollet friars, engaged

not only in missionary work in Plaisance and the surrounding areas but often

found themselves dealing with problems such as conflict with the secular

authorities of the colony, a lack of religious participation by the inhabitants,

insufficient or inconsistent funding, and problems of recruitment within their

own ranks. But again, with the publication of Plaisance, Terre-Neuve

1650-1713: Une colonie française en Amérique

(Sillery, QC: Septentrion, 2008), much of what we now know about Plaisance has

been brought together into a comprehensive single-volume treatment.

Migration and Permanent Settlement

Migration and Permanent Settlement

Even if colonization on the island of Newfoundland, whether by corporate,

private, or government sponsors, English or French, had mixed results (and the

evidence now supports those who argue that Ferryland, possibly Cupers Cove at

modern-day Cupid’s, and therefore conceivably at other locations were much more

successful than was traditionally believed), this did not preclude permanent

settlement there. A resident population did develop on the island during the seventeenth

century, and though it remained extremely small (probably no more than 2,000

people) and was constantly changing, it did persist.

An excellent survey of the relationship between the migratory fishermen and the

emerging residential fisher population is provided by James E. Candow in his

essay "Migrants and Residents: The Interplay between European and Domestic

Fisheries in Northeast North America, 1502-1854," in David J. Starkey, Jón Th.

Thór,

Ingo Heidbrink (eds.), A History of the North Atlantic Fisheries, Volume 1:

From Early Times to the Mid-Nineteenth Century (Bremen: Hauschild for the

Deutsches Schiffahrtsmuseum, 2009), pp. 416-452.

Yet the most thorough analysis

to date of the complex factors that sustained that population yet seemingly

constrained its growth is unquestionably that found in the aforementioned book by Peter Pope, Fish

Into Wine: The Newfoundland Plantation in the Seventeenth Century (Chapel

Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2004). Pope has also compressed some

of his ideas and interpretation into a succinct overview of seventeenth-century

Newfoundland inhabitancy in “Outport Economics: Culture and Agriculture in Later

Seventeenth-Century Newfoundland,” Newfoundland Studies XIX: 1 (Spring

2003; Special Issue on “The New Early Modern Newfoundland: to 1730"): 153-186.

Kenneth Norrie and Rick Szostak provide a comprehensive overview of the

transition from an essentially migratory and seasonal labour force through a

transitional era in which migrant and permanent fishermen co-exist to the point

where the permanent population became the dominant force in the Newfoundland

fishery; see “Allocating Property Rights Over Shoreline: Institutional Change in

the Newfoundland Inshore Fishery,” Newfoundland Quarterly XX: 2 (Fall

2005): 233-263. Alan G. Macpherson examines the demographic character of Newfoundland in

microcosm with a paper that focuses entirely on St. John’s; see “The Demographic

History of St. John’s, 1627-2001: An Introductory Essay,” in Alan G. Macpherson

(ed.), Four Centuries and the City: Perspectives on the Historical Geography

of St. John’s (St. John’s: Department of Geography, Memorial University of

Newfoundland, 2005), pp. 1-18. But the most provocative analysis to date of

settlement in seventeenth-century Newfoundland is surely Robert C.H. Sweeny’s

essay, “What Difference Does a Mode Make? A Comparison of Two

Seventeenth-Century Colonies: Canada and Newfoundland,” which appeared in The

William & Mary Quarterly 3rd ser., LXIII: No. 2 (April 2006): 281-304. This

was a special issue of that journal, one devoted to the theme “Class and Early

America,” and Sweeny brings a decidedly Marxist perspective to his subject, one

that is sure to generate heated debate – for instance, he characterizes

seventeenth-century Newfoundland as “the world’s first capitalist society.” In

his efforts to develop his case, Sweeny shows more than once that his

familiarity with the detail of early modern Newfoundland fisher society is not

always solid (he claims at one point that the inshore fishery used dories in the

1600s, centuries before the specialized boat-type of that name was introduced to

Newfoundland). While students should not be discouraged from using the essay,

they should probably therefore exercise more than the usual degree of caution.

Though the permanent

population remained small, it did persist, thanks in part to a number of

adaptive strategies adopted by the residents. Inhabitants supplemented their

diet and income with fur trapping and sealing, and while such activities never

replaced the cod fishery, they were significant, because both were winter

activities and they therefore complemented the summer cod fishery rather than

compete with it for the time and energy of the inhabitant. Gardening also played

a role in supporting population growth. Official reports show that the quantity

of “improved” land increased steadily through the century, enhancing the ability

of residents to feed themselves. All of these activities are described at

greater length later in this “reader’s guide.” One adaptive strategy should,

however, be mentioned here, since it had already made its appearance before the

seventeenth century ended. This is the practice of “winterhousing,” a strategy

in which residents of coastal fishing communities would break up into small

family units in the fall and disperse into the woods, to live in simple shacks

or tilts until the spring. There they would subsist by hunting, fur trapping,

and wood cutting. Winterhousing appears to have been well-established by 1696,

according to reports by Father Baudoin, who accompanied d’Iberville’s raiding

expedition against the English Shore; see Alan Williams, Father Baudoin's

War: D'Iberville's Campaigns in Acadia and Newfoundland 1696, 1697 (St.

John's: Department of Geography, 1987). According to anthropologist Philip

Smith, winterhousing appears to have been an adaptive strategy developed in

Newfoundland, rather than being imported from elsewhere, and was most prevalent

in Conception, Trinity, and Bonavista Bays where there were forests that would

support the sort of activities described. See “In Winter Quarters,”

Newfoundland Studies III: 1(Spring 1987), 1-36, “Transhumant Europeans

Overseas: The Newfoundland Case,” Current Anthropology XXVIII: 2 (April

1987), 241-250, “Européens transhumants non pastoraux de la période récente sur

la côte atlantique du Canada,” Recherches amérindiennes au Québec

XXIII: 4 (Hiver 1993-94), 5-21, and “Transhumance among European settlers in

Atlantic Canada," Geographical Journal CLXI: 1 (March 1995), 79-86, all

by Philip E.L. Smith. See also David N. Collins, “Foe, Friend and Fragility:

Evolving Settler Interactions with the Newfoundland Wilderness,” British

Journal of Canadian Studies XXI: 1 (May 2008): 35-62.

Although Pope, Smith, and others have therefore forced us to revise our assumptions

about the nature and success of Newfoundland inhabitancy in the seventeenth

century, this does not dispute the fact that it was only in the third and fourth

decades of the eighteenth century that the residential population began to

experience substantial and persistent growth. This process was largely

dependent on migration from England and Ireland that persisted into the early nineteenth century, after

which population growth was derived almost exclusively from natural increase. A

substantial literature, much of it by historical geographers, has developed to define and to

explain the population growth of Newfoundland. The complementary relationship between the

fishery and the resident population lies at the heart of C. Grant Head's Eighteenth

Century Newfoundland: A Geographer's Perspective (Ottawa: Carleton University Press,

1976). John Mannion takes a much narrower focus in exploring the same theme; in

“Population and Economy: Geographical Perspectives on Newfoundland in 1732,”

Newfoundland & Labrador Studies XXVIII: 2 (Fall 2013): 219-265, he provides

us with a detailed snapshot of residency in Newfoundland in just one year. This

essay really should be basic reading for anyone venturing into a study of

eighteenth-century Newfoundland society, for Mannion very carefully explains why

the statistics compiled annually by the naval commodores must be used with great

care, even as he concedes that, for all their flaws, those statistics are equal,

if not superior, to statistics available for the British Isles or other British

colonies at the time. Another historical geographer, W. Gordon Handcock, narrows

his perspective by focussing on just one community. He demonstrates the

relationship between commercial development in Newfoundland and the growth of

settlement very convincingly in an essay on “The Poole Mercantile Community and the Growth of Trinity 1700-1839,” The

Newfoundland Quarterly LXXX: 3(Winter 1985): 19-30. In “Business Rivalry in

the Colonial Atlantic: A Five Forces Analysis,” an unpublished paper (2013)

which is accessible at the searchable SSRN

eLibrary, Allan Dwyer is even more direct: in their efforts to extend the

cod fishery and their operations into Notre Dame Bay, competing merchants

Benjamin Lester and John Slade used access to credit through the truck system to

encourage settlement by fishing planters; they in turn hired “servants”

(contract or indentured labourers) to prosecute the summer cod fishery and

associated ancillary activities.

In short, scholars today completely reject the old myth which claimed that migratory fishing interests were responsible for discouraging settlement growth. The pioneering work of Keith Matthews, who drew attention to the obvious point that the resident population in Newfoundland originated in the same southwestern region of England in which the British fishery was based or the same southeastern Irish region where the British fishery began increasingly to acquire provisions and recruit labour. A more extensive exposition of Handcock’s analysis is provided in Soe longe as there comes noe women: Origins of English Settlement in Newfoundland (St. John’s: Breakwater Press, 1989), a work which emerged out of Handcock’s Ph.D. thesis, An Historical Geography of the Origins of English Settlement in Newfoundland: A Study of the Migration Process (PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 1979). Handcock’s conclusions are presented graphically in Plate 26 on “Trinity, 18th Century” in the HAC, I. Finally, Alan G. Macpherson examines the demographic character of Newfoundland in microcosm with a paper that focuses entirely on St. John’s; see “The Demographic History of St. John’s, 1627-2001: An Introductory Essay,” in Alan G. Macpherson (ed.), Four Centuries and the City: Perspectives on the Historical Geography of St. John’s (St. John’s: Department of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2005), pp. 1-18.

In short, scholars today completely reject the old myth which claimed that migratory fishing interests were responsible for discouraging settlement growth. The pioneering work of Keith Matthews, who drew attention to the obvious point that the resident population in Newfoundland originated in the same southwestern region of England in which the British fishery was based or the same southeastern Irish region where the British fishery began increasingly to acquire provisions and recruit labour. A more extensive exposition of Handcock’s analysis is provided in Soe longe as there comes noe women: Origins of English Settlement in Newfoundland (St. John’s: Breakwater Press, 1989), a work which emerged out of Handcock’s Ph.D. thesis, An Historical Geography of the Origins of English Settlement in Newfoundland: A Study of the Migration Process (PhD thesis, University of Birmingham, 1979). Handcock’s conclusions are presented graphically in Plate 26 on “Trinity, 18th Century” in the HAC, I. Finally, Alan G. Macpherson examines the demographic character of Newfoundland in microcosm with a paper that focuses entirely on St. John’s; see “The Demographic History of St. John’s, 1627-2001: An Introductory Essay,” in Alan G. Macpherson (ed.), Four Centuries and the City: Perspectives on the Historical Geography of St. John’s (St. John’s: Department of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 2005), pp. 1-18.

Another seminal work was John Mannion (ed.), The Peopling of Newfoundland:

Essays in Historical Geography (St. John's: Institute of Social and Economic Research,

1977), which includes essays by the editor linking merchant trading networks and permanent

settlement in western Newfoundland during the nineteenth century ("Settlers and

Traders in Western Newfoundland," pp. 234-275), one of W. Gordon Handcock’s

earliest published assessments of the relationship between the Westcountry