Je suis Alyan?

by Ghassan and Intibah Kadi

The human tragedy in Syria is one thing, and the hypocritical manner in which the West is dealing with it is an absolute shamble.

To begin with, it was the Western sphere of influence that destabilized four states in the region over the last two decades; namely Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria. One may argue that Afghanistan had been a hotspot before the US-led invasion, but certainly that invasion did not make the situation any more stable. It is heartening to see that the world has finally woken up to the fact that the West has been instrumental in creating refugees that it finds itself not wanting to deal with.

But this is not the main subject of this article.

What we should be looking at now is the wave of Syrian refugees flooding into Europe. There are many question marks about this subject, question marks that do not meet the eye without some deeper investigation.

It is not uncompassionate or inhumane to ask legitimate questions when one smells a rat, and generally speaking, when Western mainstream media are having a frenzy, there is normally a huge dead rotten rat waiting to be uncovered. It is not uncompassionate and inhumane to ask questions even when the subject matter is refugees and when human suffering is so obvious. Quite the contrary indeed, if someone is using human suffering in order to score political, or even worse, financial gain, then such a culprit should be exposed.

From this perspective, it is imperative to make the following remarks and to pose questions about the wave Syrian of refugees and the huge media coverage of the photo of the drowned little boy Aylan:

1. Early in the mark of the “War On Syria”, battles lines were not drawn yet and as the alleged freedom fighters, soon turned sectarian terrorists, started waging sectarian cleansing campaigns, many citizens were caught on the “wrong side” and they had to flee to safety. This created the initial big flood of refugees and one can clearly understand the reason behind it. Later on, as the fighting intensified, some of those safe havens turned into battle fields, and even though citizens did not fear being singled out and persecuted, they ran away to safety, and one can also understand the rationale behind such moves.

On this count, we must be aware of the fact that an estimated 80% of genuine Syrian refuges are “internal refugees”. In other words, they moved within Syria into safer areas, and many of their youth are in the Syria Army or the civilian-based National Defence Forces (NDF). A substantial percentage of those who fled Syria are either anti-government sympathizers, ie supporters of the FSA/Al-Nusra/ISIS, or simply trying to evade military service; in simple terms, deserters.

And now, four and a half years into this war, and even though the battles are still raging, most (if not all) of those battle zones have already been vacated. So the question is this, where are those recent refugees coming from? If they are indeed fleeing Syria now, which part of Syria are they leaving and for what reason? And last but not least, how did they manage to get on the boats out of Syria en route to Europe?

2. If those refugees are not leaving Syria now, then a large number of them must have been living in some refugee camp(s) outside Syria. Such camps are mainly in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. There is no evidence at all to indicate that they are leaving from either Lebanon or Jordan. The fact that Aylan’s body was found in Bodrum Turkey and that four people’s smugglers were arrested in Turkey, not to forget that the proximity of Turkey to Hungary, is all indicative that those refugees had settled in Turkey for some time before making their exodus to Europe. We must remind ourselves that while staying in refugee camps in Turkey, Syrian refugees were not allowed to leave them. This background and logical assumption stipulates two questions: Why were the refugees suddenly allowed to leave their camps? if that is the case, is there anything sinister about this timing and decision?

3. A good look at the refugees clearly reveals that most of them are young men in their late twenties to early thirties. This gender-based nature, plus the age group, and not to forget that a huge percentage of the external Syrian refugees are in fact supporters of anti-government forces, brings up the subject of their possible affiliation with Islamic fundamentalists. This easy-to-make observation carries many questions:

– Where are their families that they are allegedly trying to remove from war zones?

– Why are they not fighting the terrorists alongside the Syrian Army or NDF?

– How do we know, and more importantly, how will the Western European governments be certain that some of those young men are not in fact ISIS members or supporter?

– If accepted as refugees in the EU, and if indeed some of them are ISIS operatives, and this is a very likely possibility, is the EU going to be prepared to deal with them over and above the already-existing ISIS sleeper cells spread all over Western Europe?

4. For thousands of refugees to all decide on a route to go to Germany via Hungary cannot be by accident. Why Hungary? One would ask? Is there a sinister plot to punish Hungary? Then by whom and for what reason?

5. What is really behind the media frenzy of one poor little toddler washed up on the shores of Turkey? We may not be yet able to answer the above questions, but on this particular one, the mystery is clearing up about the frenetic and hysterical “Je Suis Charlie”-style portrayal of one poor dead Syrian child.

What has become clear is that the Aylan story has been turned into a money spinner for at least one group that wants to raise more funds in its last desperate attempt to push for a win against the people and government of Syria.

The highly dubious British charity “Hand in Hand for Syria” which is part of the sinister network against Syria, is getting funds raised in name of the drowned toddler. “Hand in Hand for Syria” has a history of fabricating evidence. Along with BBC Panorama they staged a fictitious Hollywood-style joint production “Saving Syria’s Children”, which was cobbled together in order to influence the British parliament vote back in 2013 to invade Syria. It has a huge stake in all this current media hype.

This link provides proof about the fund being set up and moneys going to “Hand in Hand for Syria” http://aylankurdi.com/2015/09/03/aylankurdi/

And these are the words of Robert Stuart, the crusader who originally exposed the joint BBC/”Hand in Hand for Syria” charade http://bit.ly/1KRMpDC

Of course many poor refugees are washed up on the shores throughout the region and we cannot discount the Aylan story out right, but we should not be surprised that the whole thing is a fabrication.

Certain questions never get answered. We may never find out who killed Kennedy, the real and full story behind September 11. What we do know is that Western media and the Murdoch tabloids have taken an oath of deception. They are unable to speak a word of truth. So before we see Obama wearing a “Je Suis Aylan” T-shirt and waves of millions follow suite like blind sheep, we should never take any Western mainstream media story at face value.

Ghassan and Intibah Kadi blog at http://intibahwakeup.blogspot.com/

The human tragedy in Syria is one thing, and the hypocritical manner in which the West is dealing with it is an absolute shamble.

To begin with, it was the Western sphere of influence that destabilized four states in the region over the last two decades; namely Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Syria. One may argue that Afghanistan had been a hotspot before the US-led invasion, but certainly that invasion did not make the situation any more stable. It is heartening to see that the world has finally woken up to the fact that the West has been instrumental in creating refugees that it finds itself not wanting to deal with.

But this is not the main subject of this article.

What we should be looking at now is the wave of Syrian refugees flooding into Europe. There are many question marks about this subject, question marks that do not meet the eye without some deeper investigation.

It is not uncompassionate or inhumane to ask legitimate questions when one smells a rat, and generally speaking, when Western mainstream media are having a frenzy, there is normally a huge dead rotten rat waiting to be uncovered. It is not uncompassionate and inhumane to ask questions even when the subject matter is refugees and when human suffering is so obvious. Quite the contrary indeed, if someone is using human suffering in order to score political, or even worse, financial gain, then such a culprit should be exposed.

From this perspective, it is imperative to make the following remarks and to pose questions about the wave Syrian of refugees and the huge media coverage of the photo of the drowned little boy Aylan:

1. Early in the mark of the “War On Syria”, battles lines were not drawn yet and as the alleged freedom fighters, soon turned sectarian terrorists, started waging sectarian cleansing campaigns, many citizens were caught on the “wrong side” and they had to flee to safety. This created the initial big flood of refugees and one can clearly understand the reason behind it. Later on, as the fighting intensified, some of those safe havens turned into battle fields, and even though citizens did not fear being singled out and persecuted, they ran away to safety, and one can also understand the rationale behind such moves.

On this count, we must be aware of the fact that an estimated 80% of genuine Syrian refuges are “internal refugees”. In other words, they moved within Syria into safer areas, and many of their youth are in the Syria Army or the civilian-based National Defence Forces (NDF). A substantial percentage of those who fled Syria are either anti-government sympathizers, ie supporters of the FSA/Al-Nusra/ISIS, or simply trying to evade military service; in simple terms, deserters.

And now, four and a half years into this war, and even though the battles are still raging, most (if not all) of those battle zones have already been vacated. So the question is this, where are those recent refugees coming from? If they are indeed fleeing Syria now, which part of Syria are they leaving and for what reason? And last but not least, how did they manage to get on the boats out of Syria en route to Europe?

2. If those refugees are not leaving Syria now, then a large number of them must have been living in some refugee camp(s) outside Syria. Such camps are mainly in Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon. There is no evidence at all to indicate that they are leaving from either Lebanon or Jordan. The fact that Aylan’s body was found in Bodrum Turkey and that four people’s smugglers were arrested in Turkey, not to forget that the proximity of Turkey to Hungary, is all indicative that those refugees had settled in Turkey for some time before making their exodus to Europe. We must remind ourselves that while staying in refugee camps in Turkey, Syrian refugees were not allowed to leave them. This background and logical assumption stipulates two questions: Why were the refugees suddenly allowed to leave their camps? if that is the case, is there anything sinister about this timing and decision?

3. A good look at the refugees clearly reveals that most of them are young men in their late twenties to early thirties. This gender-based nature, plus the age group, and not to forget that a huge percentage of the external Syrian refugees are in fact supporters of anti-government forces, brings up the subject of their possible affiliation with Islamic fundamentalists. This easy-to-make observation carries many questions:

– Where are their families that they are allegedly trying to remove from war zones?

– Why are they not fighting the terrorists alongside the Syrian Army or NDF?

– How do we know, and more importantly, how will the Western European governments be certain that some of those young men are not in fact ISIS members or supporter?

– If accepted as refugees in the EU, and if indeed some of them are ISIS operatives, and this is a very likely possibility, is the EU going to be prepared to deal with them over and above the already-existing ISIS sleeper cells spread all over Western Europe?

4. For thousands of refugees to all decide on a route to go to Germany via Hungary cannot be by accident. Why Hungary? One would ask? Is there a sinister plot to punish Hungary? Then by whom and for what reason?

5. What is really behind the media frenzy of one poor little toddler washed up on the shores of Turkey? We may not be yet able to answer the above questions, but on this particular one, the mystery is clearing up about the frenetic and hysterical “Je Suis Charlie”-style portrayal of one poor dead Syrian child.

What has become clear is that the Aylan story has been turned into a money spinner for at least one group that wants to raise more funds in its last desperate attempt to push for a win against the people and government of Syria.

The highly dubious British charity “Hand in Hand for Syria” which is part of the sinister network against Syria, is getting funds raised in name of the drowned toddler. “Hand in Hand for Syria” has a history of fabricating evidence. Along with BBC Panorama they staged a fictitious Hollywood-style joint production “Saving Syria’s Children”, which was cobbled together in order to influence the British parliament vote back in 2013 to invade Syria. It has a huge stake in all this current media hype.

This link provides proof about the fund being set up and moneys going to “Hand in Hand for Syria” http://aylankurdi.com/2015/09/03/aylankurdi/

And these are the words of Robert Stuart, the crusader who originally exposed the joint BBC/”Hand in Hand for Syria” charade http://bit.ly/1KRMpDC

Of course many poor refugees are washed up on the shores throughout the region and we cannot discount the Aylan story out right, but we should not be surprised that the whole thing is a fabrication.

Certain questions never get answered. We may never find out who killed Kennedy, the real and full story behind September 11. What we do know is that Western media and the Murdoch tabloids have taken an oath of deception. They are unable to speak a word of truth. So before we see Obama wearing a “Je Suis Aylan” T-shirt and waves of millions follow suite like blind sheep, we should never take any Western mainstream media story at face value.

Ghassan and Intibah Kadi blog at http://intibahwakeup.blogspot.com/

http://thesaker.is/je-suis-alyan/

--------------------------

God Bless our Queen Elizabeth II and our Commonwealth... we love u - from Canada - God bless our troops and yours... always... our Commonwealth Nations 3.2 BILLION

BLOGSPOT:

CANADA MILITARY NEWS: God Bless our Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Phillip/ Love her father and mom King George VI and Queen Elizabeth/Canada - the Empire/Commonwealth- 3.2 Bllion people of the Commonwealth- thrilling for us oldies /National War Memoral Canada/Queen's beloved Mounties /Governor General of Canada David Johnston and Her Excellency Sharon Johnston /Canada- Colony, Empire and now part of the Commonwealth /God bless our Queen

http://nova0000scotia.blogspot.ca/2015/09/canada-military-news-god-bless-our.html

--------------

ONE BILLION RISING- no more excuses or abuses

--------------------

CANADA:

A Journey to Achieve Belonging: Vietnamese Refugees’ Stories of Resettlement and Long-term Adaptation to Canada

Keywords:

Vietnamese refugees

Adaptation and acculturation

Resettlement locale

Narrative inquiry

Counselling

Coping strategies

Abstract:

There is a lack of literature surrounding

long-term resettlement and adaptation experiences of Vietnamese refugees

that arrived in Canada between 1979 and 1989. This study asks, “What

do the stories of Vietnamese refugees reveal about their experiences of

adapting to the Canadian host culture? Using narrative inquiry, seven

participants were interviewed about their pre-migratory, initial, and

long-term settlement. This research sought to understand challenges of

settlement in the context of locale. Thematic analysis revealed this

group made meaning of their experiences of adaptation by engaging in

actions to achieve belonging within the Canadian host culture. Bhatia’s

dialogical model of acculturation is used to explain Vietnamese

refugees’ process of acculturation. Establishing trust and validating

Vietnamese refugees’ resilience and individual coping strategies are

essential to work with this group. Counselling implications include

understanding Vietnamese help-seeking, collaboration with settlement

workers, providing education on counselling services, and facilitating

their connection to the host locale.

File(s):

=================

40th Anniversary of 60000 Vietnamese 'Boat People' Arriving in ...

www.isans.ca/40th-anniversary-of-60000-vietnamese-boat-people-arriving-in

30 Apr 2015 ... English for Everyday Living ... The flight of Vietnamese refugees began after the fall of Saigon in 1975. ... But for many so called 'Boat People', there was no such

warm reception. ... After four months inside that refugee camp, Tuan Tran

emigrated to Canada. ... Immigrant Services Association of Nova Scotia.

Vietnamese Boat People and the Founding of MISA - Immigrant ...

www.isans.ca/vietnamese-boat-people-and-the-founding-of-misa/ - Cached

29 Jun 2015 ... As part of our 35th Anniversary celebrations, ISANS will do a web post about our history once a week for the next 35 weeks. Follow along and ...

-----------------------

Canada’s Complicated History of Refugee Reception

“Ever since the war, efforts have been made by groups and individuals to get refugees into Canada but we have fought all along to protect ourselves against the admission of such stateless persons without passports, for the reason that coming out of the maelstrom of war, some of them are liable to go on the rocks and when they become public charges, we have to keep them for the balance of their lives.” (F.C. Blair, Director, Immigration Branch, 1938)

“[A]s human beings we should do our best to provide as much sanctuary as we can for those people who can get away. I say we should do that because these people are human and deserve that consideration, and because we are human and ought to act in that way.” (Stanley Knowles, MP, House of Commons, 9 July 1943)

By Stephanie Bangarth

Separated by a mere five years, these two statements reveal much about the historic contradictions of the Canadian approach in dealing with refugee crises. In fact, remove the dates and these statements would not seem out of place in the current Canadian divide over the global refugee crisis in which there are more than 60 million people fleeing war, persecution, and danger. This is a number that surpasses the amount of displaced persons at the end of the Second World War, when my father and my grandparents fled Hungary by train and horse-led wagons to come to Canada in April of 1951, but not before spending six years stateless in Austria. They were among the 120,000+ refugees who made their way to Canada between 1947 and 1953 thanks to contract labour schemes or government, family or church group sponsorships. Make no mistake, the selection criteria were guided by racial and political bias, along with a heavy dose of economic self-interest.

Of all the elements of Canada’s immigration policy, those relating to the admission of refugees have been the most controversial and the most criticized. But for much of Canadian immigration history, neither politicians nor public officials made any distinction between immigrants and refugees. It was not until the passage of the 1976 Immigration Act that refugees constituted an admissible class for resettlement. Until that time, special refugee admission schemes were made possible only with the passage of orders-in-council which suspended normal immigration regulations and permitted relaxed criteria for screening.

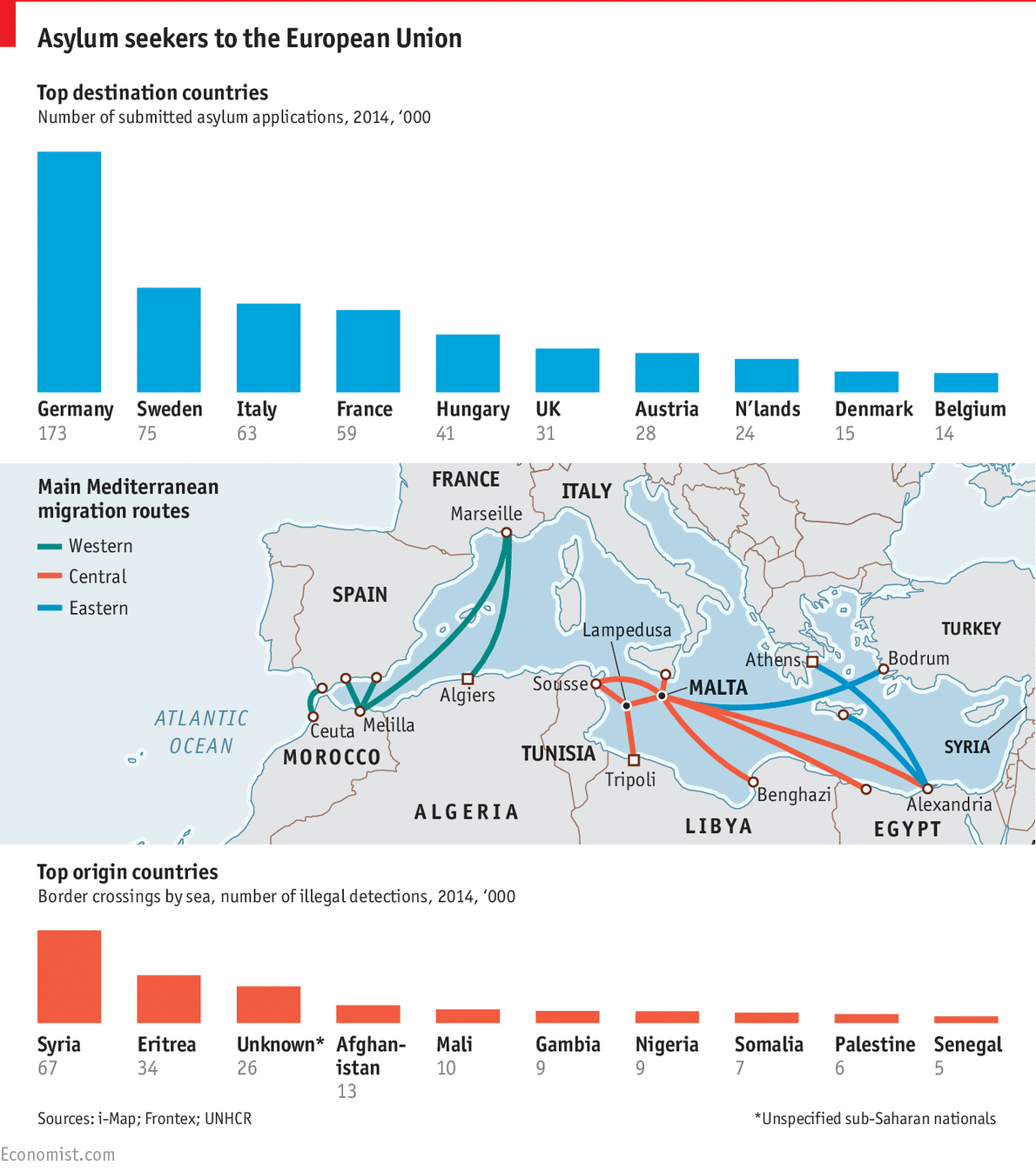

Fast forward to today and a United Nations report reveals that Canada is at the bottom of a top-15 list of industrialized receiving countries, with 13,500 claims reported in 2014. In comparison, Sweden, a small Nordic country with 9.6 million people and a quarter of Canada’s population, admitted 75,100 refugees last year. In January the Conservatives pledged to accept 10,000 Syrian refugees over a period of three years, of which Immigration Minister Chris Alexander reported 2,500 are now in Canada. In a crass display of politicking last month, the Conservatives promised to increase this number by an additional 10,000 over four years if they are re-elected in October. Sadly, this is a meaningless number, amidst an increasingly shameful Canadian response to ongoing refugee crises over the last 15 years.

We weren’t always so unwelcoming, but nor have we offered an open door since the end of World War II. I would argue that the reputation we have (or had) as a world leader in protecting refugees is due largely to the concerned Canadians who have called on our political leaders to ‘do more’. The UNHCR recognized this when it awarded the Canadian people the Nansen Medal in 1986.

In 1956 it was the Canadian people, acting in concert with humanitarian and voluntary agencies (the Canadian Red Cross in particular), who called on the government of Louis St. Laurent to take in Hungarians fleeing the violent Soviet repression of the Hungarian revolution. In response to significant public pressure, Canadian immigration officials reinforced the number of immigration officers at the Canadian Embassy in Vienna, loosened the normal requirements concerning proper travel documentation, medical exams and security clearances, and enlisted commercial airplanes to transport the refugees out of Austria. The Canadian government increased monetary aid to the CRC by emphasizing that substantial emergency relief would serve as a replacement for military intervention. The effort produced impressive results: by the end of 1957, more than 37,000 Hungarians had been accepted into Canada. This was done despite domestic economic concerns, including a rising unemployment rate. But the reception of the Hungarian refugees played well into the Cold War rhetoric of the time.

Thanks to this wellspring of Canadian support, my great aunt and uncle came to Canada in January of 1957, following a harrowing crossing over the Hungarian-Austrian border. It was actually my great uncle’s second try; he was arrested the first time and sent to a Soviet work camp. His friend wasn’t so lucky; he was shot by a Russian border guard. They are so thankful to this day for the chance to live in Canada. In fact, visit any Magyarhaz (Hungarian Hall) in Canada and you will likely find events commemorating the reception of the ‘56ers, and quite possibly a photo of J. L. Pickersgill, the Minister of Immigration at the time, who actually travelled to the refugee camps to personally assess the situation.

Still, the Hungarian refugee crisis is telling of the limits of what individuals can do in an international system founded on the primacy of the nation-state. While the response of Canadians was an important catalyst for mobilizing action around the cause of refugee rights, the crisis had the unanticipated effect of heightening expectations to what proved to be unrealistic levels. For some groups, the Hungarian crisis was not a “one-off”, but rather the standard to which future national responses to humanitarian crises should aspire. Indeed, the success of the Hungarian resettlement program for Canada served as a convenient precedent when in subsequent years, individuals and groups urged the government to act on other refugee crises.

While the Hungarian refugees were fleeing a Communist state and welcomed as democratic refugees, Chilean refugees fleeing a fascist state were viewed with suspicion. In 1973 over 7,000 Chilean and other Latin American refugees were admitted to Canada after the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende’s democratically elected Socialist–Communist government. Chilean and non–Chilean supporters of the old regime then fled the oppression directed against them by Chile’s new military ruler, General Pinochet, in the wake of the coup. Although Canada took the refugees in, it did so grudgingly—at least initially. Despite pressure from Amnesty International, church, labour, and Latino groups, the government was slow to react, not wanting to antagonize Chile’s new administration and the United States, which had deplored Chile’s slide into economic chaos under Allende. Many in the Pierre Trudeau government painted the Chilean refugees as subversives and dangerous to Canada. This was certainly out-of-step with the views of the Canadian population, many of whom were urging the government, by way of various organizations, to accept the refugees as they had done during past crises. The government was also out-of-step with the efforts of other nations, including Holland and Sweden, who treated the Chilean refugees outside the normal flow of immigrants. Only after considerable outcry from various civil society groups did the situation change.

But not all Canadians were of the same mind. The January 14, 1974 edition of the Toronto Star carried a photo of a small group of demonstrators parading in front of the Walker House Hotel, where a group of recently arrived Chileans were being temporarily housed. Carrying placards bearing statements such as “Death to the Red Pest”, “No More Marxists – FLQ was enough”, and “Keep Marxist Gangsters Out of Canada”, they claimed to be “objecting to Canadian tax money being spent on ‘riff raff’”.

The slow response in the Chilean case led many to become increasingly suspicious of Ottawa’s commitment to refugees. As several scholars of Canadian immigration and refugee policy have noted, the response to the crisis helped to foster the perception that the federal government was far more willing to accommodate refugees fleeing communist regimes on the left than those escaping fascist regimes on the right. This was made abundantly clear by the late 1970s, as Canada’s response to the “boat people” of Vietnam fleeing a leftist government was in significantly marked contrast to that which was extended, and continued to be extended to victims of right-wing regimes such as that in Chile.

By mid-1979, nearly 1.5 million refugees had fled their homes in South-East Asia. In June of 1979, the Canadian government announced that 60,000 Indochinese refugees would be resettled by the end of 1980. Thousands of Canadians came forward to welcome refugees, giving a dramatic launch to the new Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. Popular pressure forced the government to adjust upwards its initial commitment to resettling the refugees. For the years 1978-81, refugees made up 25% of all immigrants to Canada.

In the summer of 1999, several hundred undocumented Fujianese migrants (Chinese from Fujian province) arrived on Canada’s west coast, precipitating what many in the news media described as an immigration and refugee “crisis”. News coverage of these events precipitated a process of collective hand-wringing and teeth-gnashing, the result of which was that the refugees were portrayed as an embodiment of danger, a threat to the physical, moral and political security and well-being of the nation.

The alarmist reaction of the Canadian government, and Canadians, to the arrival of a vessel called the MV Sun Sea carrying Tamil refugee claimants to the West Coast in October of 2010 is consistent with our mixed history. Public Safety Minister Vic Toews warned that this was a test boat, that there would be more boat loads of Tamils arriving to overwhelm the Canadian refugee system, that the passengers might include Tamil Tigers bent on infiltrating Canada, and the whole enterprise was being driven by criminal smugglers. In reality, there were 492 claimants on the vessel, which was about 1.5% of the nearly 34,000 refugee claims Canada received that year. In response to the crisis, Toews declared that Canada should “get tough”, incarcerate all of the passengers, and possibly seek new laws to fend off this latest threat to Canada. As a result the federal government passed Bill C-31, known as the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act. To say that this piece of legislation has been soundly rejected by a variety of civil society groups would be an understatement.

So here are some numbers, again: in 1956 we took in some 37,000 Hungarian refugees. In 1968 we took in 10,000 Czechoslovakian refugees in the aftermath of the Prague Spring. In 1972, 8,000 Ugandan Asians were welcomed to Canada, and then about 60,000 Indochinese ‘boat people’ were also welcomed as refugees. In the 1990s over 11,000 refugees from the breakup of Yugoslavia made their way from Bosnia and Kosovo to Canada. And in the past decade nearly 14,000 people fleeing the ongoing civil war in Colombia have come to Canada. How many refugees is the right number? What is the right number? There’s no right answer, of course. Let’s face it; our record is mixed, even as most Canadians seem to favour asylum provision. No one should forget that in 1930s Canada, “none [was] too many” for Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany.

More recently we have seen cuts to refugee health care, mandatory detention for “irregular” arrivals (including children), and government money spent on billboards in Hungary to stem the tide of Roma asylum seekers to Canada. This is what passes for bold intervention these days. Our history with respect to refugee reception may be complicated, but over the last 10 years it has risked becoming contemptible – again.

Stephanie Bangarth is an Associate Professor in History at King’s University College at the University of Western Ontario. Her research interests are in human rights advocacy and in the immigrant experience in North America, with a particular research focus on Asian immigration and a personal/family interest in post-WWII European refugee and immigrant history

http://activehistory.ca/2015/09/canadas-complicated-history-of-refugee-reception/“[A]s human beings we should do our best to provide as much sanctuary as we can for those people who can get away. I say we should do that because these people are human and deserve that consideration, and because we are human and ought to act in that way.” (Stanley Knowles, MP, House of Commons, 9 July 1943)

By Stephanie Bangarth

Separated by a mere five years, these two statements reveal much about the historic contradictions of the Canadian approach in dealing with refugee crises. In fact, remove the dates and these statements would not seem out of place in the current Canadian divide over the global refugee crisis in which there are more than 60 million people fleeing war, persecution, and danger. This is a number that surpasses the amount of displaced persons at the end of the Second World War, when my father and my grandparents fled Hungary by train and horse-led wagons to come to Canada in April of 1951, but not before spending six years stateless in Austria. They were among the 120,000+ refugees who made their way to Canada between 1947 and 1953 thanks to contract labour schemes or government, family or church group sponsorships. Make no mistake, the selection criteria were guided by racial and political bias, along with a heavy dose of economic self-interest.

Of all the elements of Canada’s immigration policy, those relating to the admission of refugees have been the most controversial and the most criticized. But for much of Canadian immigration history, neither politicians nor public officials made any distinction between immigrants and refugees. It was not until the passage of the 1976 Immigration Act that refugees constituted an admissible class for resettlement. Until that time, special refugee admission schemes were made possible only with the passage of orders-in-council which suspended normal immigration regulations and permitted relaxed criteria for screening.

Fast forward to today and a United Nations report reveals that Canada is at the bottom of a top-15 list of industrialized receiving countries, with 13,500 claims reported in 2014. In comparison, Sweden, a small Nordic country with 9.6 million people and a quarter of Canada’s population, admitted 75,100 refugees last year. In January the Conservatives pledged to accept 10,000 Syrian refugees over a period of three years, of which Immigration Minister Chris Alexander reported 2,500 are now in Canada. In a crass display of politicking last month, the Conservatives promised to increase this number by an additional 10,000 over four years if they are re-elected in October. Sadly, this is a meaningless number, amidst an increasingly shameful Canadian response to ongoing refugee crises over the last 15 years.

We weren’t always so unwelcoming, but nor have we offered an open door since the end of World War II. I would argue that the reputation we have (or had) as a world leader in protecting refugees is due largely to the concerned Canadians who have called on our political leaders to ‘do more’. The UNHCR recognized this when it awarded the Canadian people the Nansen Medal in 1986.

In 1956 it was the Canadian people, acting in concert with humanitarian and voluntary agencies (the Canadian Red Cross in particular), who called on the government of Louis St. Laurent to take in Hungarians fleeing the violent Soviet repression of the Hungarian revolution. In response to significant public pressure, Canadian immigration officials reinforced the number of immigration officers at the Canadian Embassy in Vienna, loosened the normal requirements concerning proper travel documentation, medical exams and security clearances, and enlisted commercial airplanes to transport the refugees out of Austria. The Canadian government increased monetary aid to the CRC by emphasizing that substantial emergency relief would serve as a replacement for military intervention. The effort produced impressive results: by the end of 1957, more than 37,000 Hungarians had been accepted into Canada. This was done despite domestic economic concerns, including a rising unemployment rate. But the reception of the Hungarian refugees played well into the Cold War rhetoric of the time.

Thanks to this wellspring of Canadian support, my great aunt and uncle came to Canada in January of 1957, following a harrowing crossing over the Hungarian-Austrian border. It was actually my great uncle’s second try; he was arrested the first time and sent to a Soviet work camp. His friend wasn’t so lucky; he was shot by a Russian border guard. They are so thankful to this day for the chance to live in Canada. In fact, visit any Magyarhaz (Hungarian Hall) in Canada and you will likely find events commemorating the reception of the ‘56ers, and quite possibly a photo of J. L. Pickersgill, the Minister of Immigration at the time, who actually travelled to the refugee camps to personally assess the situation.

Still, the Hungarian refugee crisis is telling of the limits of what individuals can do in an international system founded on the primacy of the nation-state. While the response of Canadians was an important catalyst for mobilizing action around the cause of refugee rights, the crisis had the unanticipated effect of heightening expectations to what proved to be unrealistic levels. For some groups, the Hungarian crisis was not a “one-off”, but rather the standard to which future national responses to humanitarian crises should aspire. Indeed, the success of the Hungarian resettlement program for Canada served as a convenient precedent when in subsequent years, individuals and groups urged the government to act on other refugee crises.

While the Hungarian refugees were fleeing a Communist state and welcomed as democratic refugees, Chilean refugees fleeing a fascist state were viewed with suspicion. In 1973 over 7,000 Chilean and other Latin American refugees were admitted to Canada after the violent overthrow of Salvador Allende’s democratically elected Socialist–Communist government. Chilean and non–Chilean supporters of the old regime then fled the oppression directed against them by Chile’s new military ruler, General Pinochet, in the wake of the coup. Although Canada took the refugees in, it did so grudgingly—at least initially. Despite pressure from Amnesty International, church, labour, and Latino groups, the government was slow to react, not wanting to antagonize Chile’s new administration and the United States, which had deplored Chile’s slide into economic chaos under Allende. Many in the Pierre Trudeau government painted the Chilean refugees as subversives and dangerous to Canada. This was certainly out-of-step with the views of the Canadian population, many of whom were urging the government, by way of various organizations, to accept the refugees as they had done during past crises. The government was also out-of-step with the efforts of other nations, including Holland and Sweden, who treated the Chilean refugees outside the normal flow of immigrants. Only after considerable outcry from various civil society groups did the situation change.

But not all Canadians were of the same mind. The January 14, 1974 edition of the Toronto Star carried a photo of a small group of demonstrators parading in front of the Walker House Hotel, where a group of recently arrived Chileans were being temporarily housed. Carrying placards bearing statements such as “Death to the Red Pest”, “No More Marxists – FLQ was enough”, and “Keep Marxist Gangsters Out of Canada”, they claimed to be “objecting to Canadian tax money being spent on ‘riff raff’”.

The slow response in the Chilean case led many to become increasingly suspicious of Ottawa’s commitment to refugees. As several scholars of Canadian immigration and refugee policy have noted, the response to the crisis helped to foster the perception that the federal government was far more willing to accommodate refugees fleeing communist regimes on the left than those escaping fascist regimes on the right. This was made abundantly clear by the late 1970s, as Canada’s response to the “boat people” of Vietnam fleeing a leftist government was in significantly marked contrast to that which was extended, and continued to be extended to victims of right-wing regimes such as that in Chile.

By mid-1979, nearly 1.5 million refugees had fled their homes in South-East Asia. In June of 1979, the Canadian government announced that 60,000 Indochinese refugees would be resettled by the end of 1980. Thousands of Canadians came forward to welcome refugees, giving a dramatic launch to the new Private Sponsorship of Refugees Program. Popular pressure forced the government to adjust upwards its initial commitment to resettling the refugees. For the years 1978-81, refugees made up 25% of all immigrants to Canada.

In the summer of 1999, several hundred undocumented Fujianese migrants (Chinese from Fujian province) arrived on Canada’s west coast, precipitating what many in the news media described as an immigration and refugee “crisis”. News coverage of these events precipitated a process of collective hand-wringing and teeth-gnashing, the result of which was that the refugees were portrayed as an embodiment of danger, a threat to the physical, moral and political security and well-being of the nation.

The alarmist reaction of the Canadian government, and Canadians, to the arrival of a vessel called the MV Sun Sea carrying Tamil refugee claimants to the West Coast in October of 2010 is consistent with our mixed history. Public Safety Minister Vic Toews warned that this was a test boat, that there would be more boat loads of Tamils arriving to overwhelm the Canadian refugee system, that the passengers might include Tamil Tigers bent on infiltrating Canada, and the whole enterprise was being driven by criminal smugglers. In reality, there were 492 claimants on the vessel, which was about 1.5% of the nearly 34,000 refugee claims Canada received that year. In response to the crisis, Toews declared that Canada should “get tough”, incarcerate all of the passengers, and possibly seek new laws to fend off this latest threat to Canada. As a result the federal government passed Bill C-31, known as the Protecting Canada’s Immigration System Act. To say that this piece of legislation has been soundly rejected by a variety of civil society groups would be an understatement.

So here are some numbers, again: in 1956 we took in some 37,000 Hungarian refugees. In 1968 we took in 10,000 Czechoslovakian refugees in the aftermath of the Prague Spring. In 1972, 8,000 Ugandan Asians were welcomed to Canada, and then about 60,000 Indochinese ‘boat people’ were also welcomed as refugees. In the 1990s over 11,000 refugees from the breakup of Yugoslavia made their way from Bosnia and Kosovo to Canada. And in the past decade nearly 14,000 people fleeing the ongoing civil war in Colombia have come to Canada. How many refugees is the right number? What is the right number? There’s no right answer, of course. Let’s face it; our record is mixed, even as most Canadians seem to favour asylum provision. No one should forget that in 1930s Canada, “none [was] too many” for Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany.

More recently we have seen cuts to refugee health care, mandatory detention for “irregular” arrivals (including children), and government money spent on billboards in Hungary to stem the tide of Roma asylum seekers to Canada. This is what passes for bold intervention these days. Our history with respect to refugee reception may be complicated, but over the last 10 years it has risked becoming contemptible – again.

Stephanie Bangarth is an Associate Professor in History at King’s University College at the University of Western Ontario. Her research interests are in human rights advocacy and in the immigrant experience in North America, with a particular research focus on Asian immigration and a personal/family interest in post-WWII European refugee and immigrant history

---------------------

-------------

The impact of Syria’s refugee crisis on the Middle East has been immense. Turkey hosts more than 1.5 million Syrian refugees, Lebanon is home to 1.1 million, and Jordan has registered nearly 620,000, the UNHCR said. Iraq hosts 232,800 Syrian refugees and Egypt close to 136,000.

These five countries host 97% of Syria’s refugees, according to Amnesty International. About 80,000 Syrians live in Jordan’s Zaatari refugee camp, making it the country’s fourth largest city.

------------------

Syrian refugees in Lebanon surpass one million

Press Releases, 3 April 2014

Lebanon faces intensifying spillover; host communities stretched to breaking point

Beirut/Geneva, 3 April 2014 – The number of refugees fleeing from Syria into neighbouring Lebanon surpassed 1 million today, a devastating milestone worsened by rapidly depleting resources and a host community stretched to breaking point.Three years after Syria's conflict began, Lebanon has become the country with the highest per-capita concentration of refugees worldwide, struggling to keep pace with a crisis that shows no signs of slowing.

Refugees from Syria now equal one-quarter of the resident population, with over 220 Syrian refugees for every 1,000 Lebanese residents.

"The influx of a million refugees would be massive in any country. For Lebanon, a small nation beset by internal difficulties, the impact is staggering," said António Guterres, UN High Commissioner for Refugees. "The Lebanese people have shown striking generosity, but are struggling to cope. Lebanon hosts the highest concentration of refugees in recent history. We cannot let it shoulder this burden alone."

The influx is accelerating. In April 2012, there were 18,000 Syrian refugees in Lebanon; by April 2013, there were 356,000, and now, in April 2014, 1 million. Every day, UNHCR in Lebanon registers 2,500 new refugees: more than one person a minute.

The impact on Lebanon has been immense. The country has experienced serious economic shocks due to the conflict in Syria, including a decline in trade, tourism and investment and an increase in public expenditures. Public services are struggling to meet increased demand, with health, education, electricity, and water and sanitation particularly taxed.

The World Bank estimates that the Syria crisis cost Lebanon US$2.5 billion in lost economic activity during 2013 and threatens to push 170,000 Lebanese into poverty by the end of this year. Wages are plummeting, and families are struggling to make ends meet.

Children make up half the Syrian refugee population in Lebanon. The number of school-aged children is now over 400,000, eclipsing the number of Lebanese children in public schools. These schools have opened their doors to over 100,000 refugees, yet the ability to accept more is severely limited.

Local communities feel the strain of the influx of refugees most directly, with many towns and villages now having more refugees than Lebanese. Across the country, critical infrastructure is stretched to its limits, affecting refugees and Lebanese alike. Sanitation and waste management have been severely weakened, clinics and hospitals are overstretched, and water supplies depleted. Wages are falling due increase labour supply. There is growing recognition that Lebanon needs long-term development support to weather the crisis.

"International support to government institutions and local communities is at a level that, although slowly increasing, is totally out of proportion with what is needed," Mr. Guterres said. "Support to Lebanon is not only a moral imperative, but it is also badly needed to stop the further erosion of peace and security in this fragile society, and indeed the whole region."

And while the scale of the humanitarian emergency expands, and the serious consequences to Lebanon mount, the humanitarian appeal for Lebanon is only 13 per cent funded.

Aid agencies struggle to prioritise equally compelling needs and target assistance first and foremost to most vulnerable of a needy population. Limited humanitarian funding coupled with a steady erosion of refugees own reserves can have dire consequences. A growing number of refugees are unable to afford or to find suitable accommodation and are resorting to insecure dwellings such as tents, garages and animal sheds. 80,000 urgently need health assistance. More than 650,000 receive monthly food aid to survive.

The vast majority of children are out of school, many work, girls can be married young and the prospect of a better future recedes the longer they remain out of school.

"The Syrian children of today," said Ninette Kelley, "will be the shapers of Syria tomorrow. We must ensure they have the skills to meet the vast challenges they are now consigned to confront in years to come."

UN and partner agencies have mounted an unprecedented response, targeting both refugees and Lebanese host communities. Late last year, they appealed for US$1.89 billion for 2014. Only US$242 million has been received so far.

"Lebanese communities are increasingly hard-pressed, and tensions are rising," Ms. Kelley said. "Yet relocation spaces to wealthier third countries remain limited, and the appeal remains woefully underfunded. Morality and pragmatism demand we do more."

Photos, video, infographics and other media materials can be downloaded from http://www.unhcr.org/lebanon1m

For more information, please contact:

- Beirut: Dana Sleiman (+961 71 910 626) – including for interviews with Ninette Kelley

- Beirut: Joelle Eid (+961 70 176 969)

- Bekaa Valley: Lisa Abou Khaled (+961 71 880 070)

- Tripoli: Bathoul Ahmed (+961 70 100 740)

- Geneva: Dan McNorton (+41 79 217 3011)

- Geneva: Ariane Rummery (+41 79 200 76 17)

-------------------------

Lebanon and Jordan host almost 2 million refugees while the rich Gulf states host none

--------------

AND IRAN....

Why Some Arabs States Refuse to Accept Syrian Refugees

Syrians fleeing war are driven to board precarious boats to cross the Mediterranean. They crowd onto trains and climb mountains. They risk detention, deportation, and drowning.

There is growing evidence that the people dying to reach the shores of Europe are fleeing not only war in Syria, but oppression in other Middle Eastern states.

As pressure rises for European leaders to resolve the refugee crisis, critics are also asking why Middle Eastern governments have not done more to help the four million Syrians who represent one of the largest mass movement of refugees since World War Two. Much ire has focused on the relatively wealthy states along the Persian Gulf. According to a report by Amnesty International, the six countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council offered zero formal resettlement slots to Syrians by the end of 2014.

Read about changes to Time.com

Rights groups point out that those countries — Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) — with wealth amassed from oil, gas, and finance, collectively have far more resources than the two Arab states that have taken in the most Syrians: Jordan and Lebanon. The Gulf states are Arabic-speaking, have historic ties to Syria and some are embroiled in the current crisis through their support for insurgent groups.

“The missing linkage in this tragic drama is the role of Arab countries, specifically the Gulf countries,” says Fadi al-Qadi, a regional human rights expert in Jordan. “These states have invested money, supported political parties and factions, funded with guns, weapons et cetera, and engaged in a larger political discourse around the crisis.”

Supporters of Gulf governments contend that such criticism is unwarranted. The Gulf states have donated tens of millions of dollars to help Syrian refugees in places like Jordan. Saudi Arabia claims it has admitted half a million Syrians since 2011. Syrians are welcome to come, the argument goes, even if they are not legally registered as refugees.

Rights groups are not convinced. Visa restrictions make it difficult for Syrians to enter Gulf countries in practice, and even harder to stay. “These countries are not making clear, logistically and technically, to these people that your destination could be the Gulf,” says Qadi. “They have to make it clear. They have to announce it.”

The logic behind Gulf refugee policies is complex. In smaller Gulf states like Qatar and the UAE, foreigners already far outnumber nationals, a demographic balance that, for some, feeds feelings of anxiety tinged with xenophobia. In the UAE, foreign nationals outnumber citizens by more than five to one.

Elsewhere in the Middle East, Syrians fleeing the slaughter in their country often face a bleak landscape with few opportunities to work, attend school, reunite with their families, and start new full lives.

Lebanon has accepted more than 1.1 million Syrians, the most of any Arab state (Turkey has accepted approximately two million). That means that at least one in five people in Lebanon is a Syrian refugee. Lebanon forbids the construction of formal refugee camps. As a result, more than 40% of refugees in Lebanon live in makeshift shelters including “garages, worksites, one room structures, unfinished housing,” according to U.N. figures cited by Amnesty International. Many Syrians rely on aid agencies whose resources are stretched thin.

In Egypt, state repression is part of what is compelling Syrians to risk the sea route to Europe. Following the military’s overthrow of elected president Mohamed Morsi in 2013, Egypt demand Syrians apply for visas. Morsi’s Islamist government was sympathetic to the rebel cause in Syria, but the new military-backed regime is less sympathetic to Syrian migrants many more have been deported. Coinciding with a tide of Egyptian nationalism, Syrians reported being fired from their jobs, detained by police, and harassed by landlords.

Bassam al-Ahmad, an official with the Violations Documentation Center, a Syrian human rights group, said that tightening restrictions on Syrians’ entry across the region is helping drive the wave of migration to Europe.

“I cannot go to Egypt. It’s kind of like the circle became very, very narrow. In Lebanon it’s similar,” he says in a phone interview from Istanbul. “All of this pushes people to go to the sea. It’s like going to die, going to death.”

Inside Syria, the bloodshed continues, driving more and more Syrians to flee into the unknown. As a result of this carnage, Qadi says, most Syrians are facing a decision to stay or flee. That is the source of what is now understood in Europe as a refugee crisis. “The bomb is coming anyway, and it will destroy this house, and my kids will be gone,” he says. “Would I take another risk by trying to escape before the bomb comes? And go to the unknown? I think most Syrians are making that difficult choice.”

http://time.com/4025187/arab-states-syrian-refugees/

----------------

The Economist explains

Everything you want to know about migration across the Mediterranean

Migrants leaving from north Africa for Italy do so overwhelmingly from Libya, though there are also routes to Italy from Egypt and Morocco, and from Turkey to Greece. A 2013 report for the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), by Altai consulting, estimates that the cost of getting to Libya varies from about $200 to $1,000 from west Africa, and from about $1,000 to $6,000 from the Horn of Africa. Subsequent transit by sea runs from a few hundred dollars to a couple of thousand. At the coast passengers are either loaded onto rigid inflatable boats with limited fuel and no captain or guide to help them or are herded onto rickety fishing boats which do have a skipper and crew.

The journey from Libya to Italy is a couple of hundred kilometres—less than a day's sail—but the boats are not necessarily intended to get all the way. Once clear of the Libyan coast, a distress call is made in the hope that the migrants will be picked up either by a passing merchant ship or fishing boat or by the Italian or Maltese coast guards. In cases where the vessel is crewed, the crew members flee or try to pass as migrants, often successfully.

Why are people risking this awful journey?

Because they are fleeing some mixture of war, oppression, civil disorder and poverty. Most of the migrants are young men. They make their journeys in sections, stopping and working at various places along the route. According to Italian estimates there are between 500,000 and one million currently in Libya awaiting passage; living conditions are usually bad, but most migrants have no way back to where they came from.

Where are most migrants coming from?

The make-up of the flows has changed over the years. Migrants currently come mainly from west Africa, the horn of Africa and, since 2013, Syria. Last year, according to the UNHCR, 31% of arrivals were Syrians, and 18% were fleeing Eritrea. So far this year the flow to Italy is dominated by migrants from the Gambia, Senegal and Somalia. There are routes through the Sahara from both west Africa and the Horn of Africa; there are also some routes along the Mediterranean coast. For many of the communities along the way the traffic in would-be migrants is now a dominant part of the local economy. (Story continues below the chart)

The vast majority of those who leave Libya end up in Italy—often the small island of Lampedusa. Greece and Malta are also common destinations. The European Union's Dublin regulation says that the first EU country a migrant gets to must take responsibility for him; southern countries say this puts puts a great deal of the burden of border management on them. Germany, France and Britain, though, say they end up taking more refugees and migrants, both because of migration along other routes (for example, through the Balkans) and because southerners encourage migrants to move northwards. Reaching an agreement on an equitable distribution of the burden has not yet proved possible, largely because of political sensitivity to immigration in northern countries. On a per capita basis, Sweden has taken by far the largest share of Europe’s Syrian refugees.

Why is the journey so dangerous? Don't people sail around safely on the Med all the time?

The boats used are old and often of dubious seaworthiness; their crews often abandon them. They are also severely overcrowded. The boat that sank on April 19th was about 20 metres long and carrying more than 900 people, many of them locked below decks; it appears to have capsized when those on deck rushed to one side, seeking to board a ship offering to rescue them.

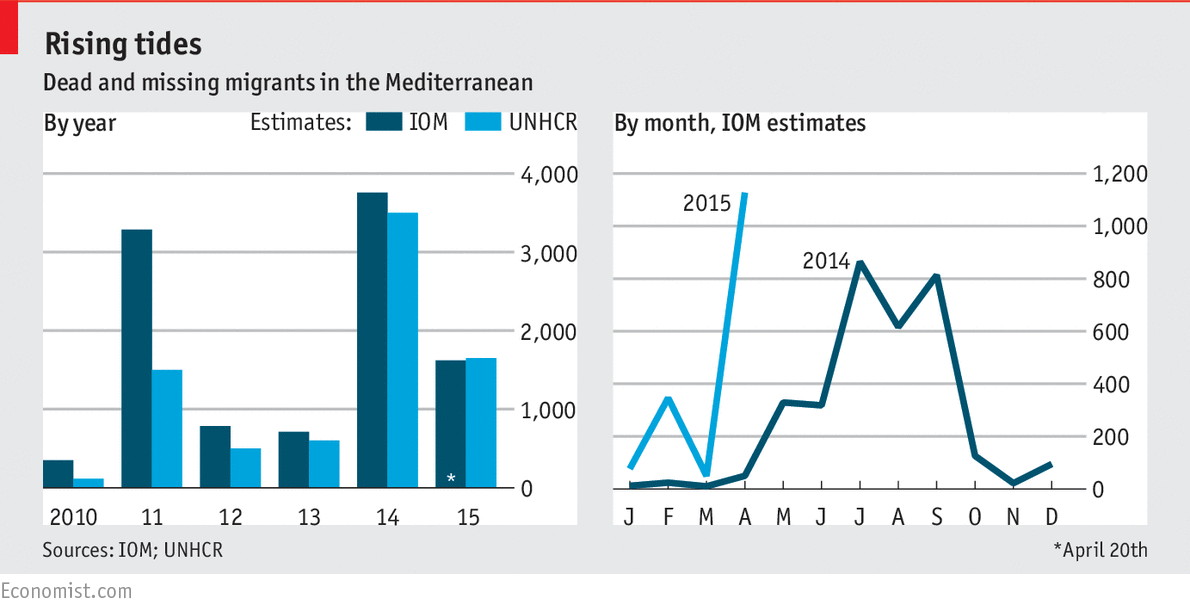

Is migration becoming more dangerous over time? Why are more people dying?

The UNHCR estimates that 26,165 migrants have reached the shores of Italy this year, a similar number to the 26,644 who arrived in the first four months of 2014. However in the first four months of 2014 only 96 are thought to have died, as opposed to an estimated 1,700 so far this year. The main difference in circumstance is that in early 2014 the Italian navy was operating a thoroughgoing interception operation called Mare Nostrum, which was set up after an earlier wreck off Lampedusa in which hundreds died. Mare Nostrum intercepted ships carrying migrants in international waters and became the de facto last stage of most migrants’ journey to Europe. More than 140,000 people were taken on board its ships from October 2013 to October 2014. At that point it was replaced by an operation called Triton, run by the EU’s border agency, Frontex, which only operates within 50km of the Italian coast. Among the arguments for this new, cheaper option was the idea that, if shutting down Mare Nostrum made the passage riskier, then fewer would attempt it. This appears not to have been the case; the change of policy seems simply to have driven the death toll up. (Story continues below the chart)

For something more ambitious to work, a better way of distributing the refugees around Europe will be necessary. Operations aimed at destroying the smugglers’ ships have been mooted, but pose several risks: military action might increase instability in Libya while encouraging the smugglers to use smaller yet less-seaworthy boats. Peace and a return to effective government control along the Libyan coast could bring with it the sort of stability that lets people earn their living from work other than smuggling, as well as a police presence capable of reining in illegal migration. Yet bringing peace to North Africa and the Middle East is an even harder problem than ending the migration crisis. Doing more for Syrian refugees in other Arab countries might help, but given the large number of migrants already in Libya it would take time to have any effect. It is also possible that applications for European asylum could be processed in north Africa, but although this idea has been gaining support there has been no concrete progress. Again, it is unlikely to be workable without a resolution to the impasse over the distribution of refugees across Europe.

This piece has been updated to reflect news.

Dig deeper:

Europe's disastrous migration policy is a moral failure (April 2015)

http://www.economist.com/blogs/economist-explains/2015/05/economist-explains-6

---------------------

More

eyewitness descriptions from tourists visiting Lesbos, Greece.

Related articles:

• Tourist about boat “refugees”: “The young men we saw every day were well-dressed, spoke in iPhones, were well-fed … ONLY men”

• Hungary: 11,000 illegals cross border every month, hysterical Islamic riots, stoning of police and of random cars…

• Shocking photos and video of illegal immigrants hijacking trucks to get to England

• UN chief of migration: EU must destroy homogeneity of member states through immigration

• Denmark: 72-year-old woman homeless because state gives her apartment to refugees

• Tourist about boat “refugees”: “The young men we saw every day were well-dressed, spoke in iPhones, were well-fed … ONLY men”

• Hungary: 11,000 illegals cross border every month, hysterical Islamic riots, stoning of police and of random cars…

• Shocking photos and video of illegal immigrants hijacking trucks to get to England

• UN chief of migration: EU must destroy homogeneity of member states through immigration

• Denmark: 72-year-old woman homeless because state gives her apartment to refugees

Translated from a letter in JP by a Danish female doctor and politician:

“My family and I were on Lesbos two months ago, and

we met many boat refugees. We bought bread and water, which we handed out for

two days. Then we found out, however, that the refugees were not impoverished,

hungry or thirsty …

While one can only rejoice at Danish tourists’

thoughtfulness when they bring toys, sleeping bags, clothes, etc. to the

refugees on Lesbos, these are not things that the refugees can use. They

quickly leave via Athens for the Netherlands and Scandinavia. The refugees does

not stay longer on Lesbos than one or two days, and they can only carry

essentials on their further travel.

My experience is that over 80 percent of the boat people are young men

about 20 years old. Many wear Rayban sunglasses and Nike caps (probably counterfeit goods). They are not shabbily

dressed and do not need the presented clothes. I felt great empathy with this

army of refugees, but after a few days more questions presented themselves.

Where will all these men live? How many will integrate?

[…]

Why are Saudi Arabia not taking in Syrian refugees,

when they have the same culture? Saudi Arabia is 50 times larger than Denmark.

Its gross domestic product is one to one and a half times bigger as Denmark.

Saudi Arabia has both space and money enough to

receive refugees. When a Syrian chooses to flee to Denmark, it would correspond

to my father fleeing during World War II to Sudan instead of fleeing to

Sweden.… Refugees should be in their neighborhood.”

----------

BLOGSPOT

CANADA MILITARY NEWS: The World's Hate John 15:17-27 / What does CANADA'S SOLDIER- Romeo Dallaire -Rwanda's Saviour say/ Pope Francis calls on us- let's get cracking/no excuse Canadians for voting-Afghan women did/Vietnam Boat Movement/Rwanada/UN complete betrayal of world's humanity- gotta go /Wish we could have sponsored Anne Frank...as WWII children she was our hero... so brave...so good...so decent/ Desiderata

---

BLOGSPOT

CANADA MILITARY NEWS- God's Watching- Remembering Katrina...post to troops and personal observations 2009/Waylon Jennings -House of the Rising Sun for Katrina/ Why is the kindness and goodness of our Christian nations so horrifically abused with $$$$trillions of 50 years fed in2 waste and despots and thieves pockets? why?-The Foreign Aid Debate/why we still believe in decency and good of each other 2 still give as Canadians in a jaded-faded world -and will because it's just right-God's watching

--------------

-----------

Forget the ‘war on smuggling’, we need to be helping refugees in need

An

Oxford academic argues that the Indochinese response to the Vietnamese

boat people could provide a framework for a solution to the crisis in

the Mediterranean

The Indo-Chinese response to the Vietnamese boat people could provide a

framework for an EU solution. Photograph: Express Newspapers/Getty

Images Alexander Betts

The Indo-Chinese response to the Vietnamese boat people could provide a

framework for an EU solution. Photograph: Express Newspapers/Getty

Images Alexander Betts

The

crisis in the Mediterranean, which has led to more than 1,700 deaths already

this year, has evoked an immediate response from European political leaders.

Yet the EU response fundamentally and wilfully misunderstands the underlying

causes. It has focused increasingly on tackling smuggling networks, reinforcing

border control and deportation. Somehow European politicians have managed to

turn a human tragedy into an opportunity to further reinforce migration control

policies, rather than engage in meaningful international cooperation to address

the real causes of the problem.

The deaths in the Mediterranean have two main causes.

First, the abolition in November 2014 of the successful Mare Nostrum

search-and-rescue programme, which saved more than 100,000 lives

last year, immediately led to a reduction in the number of rescues and an

increase in the number of deaths.

Second, and most importantly, there is a global displacement

crisis. We know that in last week’s tragedy – as with wider data on this year’s

Mediterranean crossings – a growing proportion are coming from

refugee-producing countries such as Syria, Eritrea and Somalia. These people

are fleeing conflict and persecution. Of course, others are coming from

relatively stable countries such as Senegal and Mali, but the majority now are

almost certainly refugees.

Around the world there are currently more displaced

people than at any time since the second world war. More than 50 million people

are refugees or internally displaced, and the current international refugee

regime is being stretched to its absolute limits. For example, there are nine

million displaced Syrians, of whom three million are refugees.

The overwhelming majority are in neighbouring

countries such as Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey. A quarter of Lebanon’s entire

population is now made up of Syrian refugees. Yet the capacity of these states

is limited. Faced with this influx, Jordan and Lebanon have closed their

borders to new arrivals. But these people have to go somewhere to seek

protection and, with few alternatives, increasing numbers are making the

perilous journey across the Mediterranean to Europe.

In this context, there are no easy solutions. Yet European

politicians are taking the easy option of failing to understand the wider world

of which Europe is a part. From early last week, Italy’s prime minister, Matteo

Renzi, focused on proclaiming a “war on trafficking”. Politicians across Europe

followed suit. Yet this fails to recognise that smuggling does not cause

migration; it responds to an underlying demand. Criminalising the smugglers

serves as a convenient scapegoat, but it cannot solve the problem. Rather like

a “war on drugs”, it will simply displace the problem, increase prices,

introduce ever less scrupulous market entrants and make the journey more

perilous.

The proposals to emerge from last week’s emergency EU

meetings in Luxembourg and Brussels have been similarly disappointing. They

have focused on destroying the vessels of smugglers and committing to higher

levels of rapid deportation, presumably to unstable and unsafe transit

countries such as Libya. The humanitarian provisions of the plans have been

vague and problematic. The EU has committed to triple funding for Operation

Triton. Yet unlike the abolished Mare Nostrum, that operation has never had a

search-and-rescue focus. As the head of the EU border agency, Frontex, has

explained, it is primarily a border security operation with little capacity to

save lives.

The problem is far broader than a border control

issue; it goes to the heart of the way in which we collectively protect and

assist refugees and displaced populations. The global refugee regime, based on

the 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees,

creates an obligation on states to protect and assist refugees who reach their

territory, yet around the world its core principles are under threat. This is

not only the case in Europe. Australia’s Pacific Solution, which prevents “boat

people” arriving, is an abdication of legal responsibility. In the aftermath of

the Garissa attacks, Kenya recently announced a proposal to close the Dadaab

camps, home to hundreds of thousands of Somali refugees. In both the global

north and south, the right of refugees to seek asylum is being eroded.

Yet the rights of refugees to seek asylum have to be

sacrosanct. We collectively created the global refugee regime in the aftermath

of the second world war because Europe recognised the absolute obligation to

ensure that people facing persecution would have access to effective protection

on the territory of another state. As it did in the early 1950s, courageous

European leadership is again needed to repair that international system and

reinforce fundamental human rights standards, within and beyond the EU.

There is a fundamental inequality in the existing

global refugee regime. It creates an obligation on states to protect those

refugees who arrive on the territory of a state (“asylum”), but it provides few

clear obligations to support refugees who are on the territory of other states

(“burden-sharing”). This means that inevitably states closest to

refugee-producing countries take on a disproportionate responsibility for

refugees. This inequality is a problem within Europe, but it also exists on a

global scale. It is the reason why more than 80% of the world’s refugees are

hosted by developing countries.

In order to enable this system to function – and sustain

the willingness of countries like Jordan, Lebanon and Kenya to host refugees –

a serious ongoing commitment to refugee protection needs to be maintained by

countries outside regions of origin. This is even more important when “we”

arguably have a moral responsibility – through our foreign policies – for the

destabilisation of countries such as Syria and Libya.

One way of protecting refugees and engaging in

international cooperation is through resettlement. Many countries, such as the

US, Canada and Australia, have a history of resettling refugees directly from

camps and urban areas. Europe does not generally have that tradition; in

response to the Syrian crisis, resettlement numbers have been comparatively

tiny. The proposal for a “voluntary” European resettlement scheme for 5,000

refugees to emerge at last week’s Brussels meeting is absurd against the

backdrop of three million Syrian refugees.

There are instructive lessons from history on the

kinds of international cooperation that could reinforce the refugee regime and

make a difference in the Mediterranean. After the end of the Vietnam war in

1975, hundreds of thousands of Indochinese “boat people” crossed territorial

waters from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia towards south-east Asian host states

such as Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines and Hong Kong.

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, the host states, facing an influx, pushed many

of the boats back into the water and people drowned. Like today, there was a

public response to images of people drowning on television and in newspapers,

but addressing the issue took political leadership and large-scale

international cooperation.

In 1989, under UNHCR leadership, a Comprehensive Plan

of Action (CPA) was agreed for Indochinese refugees. It was based on an

international agreement for sharing responsibility. The receiving countries in

south-east Asia agreed to keep their borders open, engage in search-and-rescue

operations and provide reception to the boat people.

However, they did so based on two sets of commitments

from other states. First, a coalition of governments – the US, Canada,

Australia, New Zealand and the European states – committed to resettle all

those who were judged to be refugees. Second, alternative and humane solutions,

including return and alternative, legal immigration channels were found for

those who were not refugees in need of international protection. The plan led

to millions being resettled and the most immediate humanitarian challenge was

addressed.

The Indochinese response was not perfect and it is

not a perfect analogy to the contemporary Mediterranean, but it highlights the

need for a broader framework based on international cooperation and

responsibility-sharing.

The elements of a solution to the contemporary crisis

have to be at a number of different levels. Above all, though, solutions have

to come from a reaffirmation of the need to uphold asylum and refugee

protection, and to see these as a shared global responsibility. If there is to

be a silver lining to the current crisis, it stems from the opportunity for

political leadership to reframe how refugees are seen by the public and to come

up with creative solutions for refugees on a global scale. But that will take

political courage and leadership.

Alexander Betts is director of the Refugee Studies

Centre at the University of Oxford and the author of Survival Migration: Failed

Governance and the Crisis of Displacement (Cornell University Press). Twitter:

@alexander_betts

-------------

Welcome to Italy: this is what a real immigration crisis looks like

With 50,000 boat people in just six months, and more to come, the politics of asylum here is becoming increasingly toxic

Let us suppose that along the coast of Normandy up to one million non-EU migrants are waiting to be packed like sardines in small unseaworthy vessels and to cross the English Channel.

Let us suppose that first the Royal Navy, then the navies of a dozen other EU countries, start to search for all such vessels in the Channel right up to the French coast, out into the North Sea and the Atlantic even, and then ferry all the passengers on board to Dover, Folkestone, Hastings, Eastbourne and Brighton in a surreal modern-day never-ending version of the Dunkirk evacuation of 1940. Would the British government agree to take them all? What of the British people? And if they did agree, what would the British government and people do with all the migrants? How would they cope?

Well, Italy has been invaded in just this way, by migrants from many nations all coming over here from Libya. And Italy’s unelected government has agreed to take them all. This makes the Italian people — who are among the least racist in Europe — very angry. It’s hard to blame them.

In October 2013, Italy’s previous unelected government, which like the current one was left-wing, ordered the Italian navy to search for and rescue all boat people in the Sicilian channel and beyond. This hugely expensive operation — ‘Mare Nostrum’ — ran until October last year and rescued nearly 190,000 people. The Italian government took this decision after a migrant boat sank with the loss of 360 lives 500 yards from an idyllic beach on the island of Lampedusa, once a resort of choice for the right-on rich.

The same left-wing Italian government also took the extraordinary step of decriminalising illegal immigration, which means among other things that none of the boat people are arrested once on dry land. Instead, they are taken to ‘Centri di accoglienza’ (welcome centres) for identification and a decision on their destinies. In theory, only those who identify themselves and claim political asylum can remain in Italy until their application is refused — or, if it is accepted, indefinitely. And in theory, under the Dublin Accords, they can only claim political asylum in Italy — the country where they arrived in the EU. In practice, however, only a minority claim political asylum in Italy. Pretty well all of them remain there incognito, or else move on to other EU countries.

Here’s how it works. In the welcome centres, they are given free board and lodging plus mobile phones, €3 a day in pocket money, and lessons — if they can be bothered — in such things as ice-cream-making or driving a car and (I nearly forgot) Italian. Their presence in these welcome centres is voluntary and they are free to come and go, though not to work, and each of them costs those Italians who do pay tax €35 a day (nearly €13,000 a year). Yes, they are supposed to have their photographs and fingerprints taken, but many refuse and the Italian police, it seems, do not insist. As the Italian interior minister, Angelino Alfano, explained to a TV reporter the other day: ‘They don’t want to be identified here — otherwise, under the Dublin Accords, they would have to stay in our country. So when a police officer is in front of an Eritrean who is two metres tall who doesn’t want his fingerprints taken, he can’t break his fingers, but must respect his human rights.’

This year, there is space for just 75,000 migrants in such places. Hotels are filling the breach, including the four-star Kulm hotel perched high above the luxury resort of Portofino on the Ligurian coast. But most of the rescued migrants could not care less about all that jazz and have just disappeared.

The ones who stay long in the welcome centres are those who have revealed their identities in order to apply for political asylum in Italy. Last year, 64,900 migrants did so in Italy — roughly a third of those saved by the Italian navy. But this being Italy, the judicial system only had time to reach a decision on half those applications (accepting 60 per cent of them), and anyway, thanks to the byzantine Italian appeals procedure, those refused asylum can remain for years. Even if their asylum claim is finally rejected and by some cruel quirk of fate they are actually handed a deportation order, it is easily ignored: last year Italy forcibly deported just 6,944 people — a figure set to shrink even more once a law before parliament is passed banning deportation to countries where human rights are abused.

Fair enough, you might say, if all the asylum seekers were genuine refugees from war zones. But contrary to the impression given by most of the world’s media, hardly any of 2014’s intake were from war-torn countries such as Syria or Iraq (though it is true that the number of Syrians is now rising).