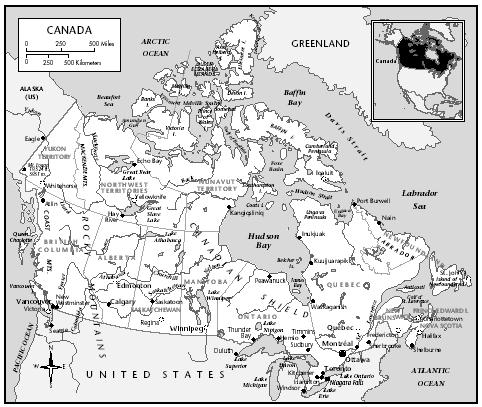

Many scientists believe that the first people to settle in the Americas came from Siberia during the ice age, when a land bridge connected Asia to North America ... (today USA and Canada)

----------------

UPDATE: - BEST ARTICLE EVER... CANADA...

Scapegoating

Cornwallis: Who are we to judge history?

July

17, 2015-07-19

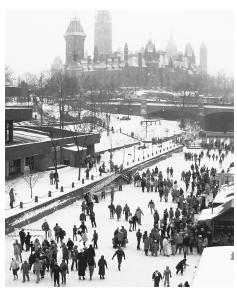

When an expedition from New England captured Louisbourg in 1745, no one was more surprised than the New Englanders. The next year, a French fleet under the Duc D’Anville that was sent out to retake the fortress anchored in Bedford Basin, which resulted in countless Mi’kmaq dying from European diseases, writes John Boileau. (LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA)

While conducting research for my 2012 book, Halifax and Titanic, I came across the following quote from Daniel Allen Butler, the American author of another Titanic book:

“There is something horribly hypocritical about passing judgment on another human being’s actions from the comfort and safety of an armchair. Even more hypocritical is making moral pronouncements on others’ actions having judged them by moral standards that they neither knew nor could conceive.”

This phenomenon has become so common that it has even been given a name: “Presentism” is the anachronistic introduction of present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past.

I believe that’s what Dan Paul has done in his July 9 letter (“Reconciliation When?”). His treatment of Edward Cornwallis (governor of Nova Scotia/Acadia from 1749 to 1752) is one-sided, unbalanced, revisionist and applies today’s standards to 18th century colonial warfare.

Conquest and colonization

did not suddenly begin around 1500 when Western Europeans commenced the

founding of their overseas empires. Conquest was not just something undertaken

by “dead white men.” Many other races and ethnic groups established empires during

the course of history.

Conquest

and colonization date back to the time when humans first walked erect.

Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Macedonians, Romans, Chinese, Arabs, Ashanti,

Moguls, Mongols, Angles, Saxons, Normans, Incas, Aztecs, Zulus and Turks — to

name but a few — invaded other regions, conquered locals and took over their

areas for their own. Western Europeans are simply among the latest groups in

this timeless march of conquest. This does not make it right; it is simply an

indisputable fact of human history.

Outside

the British House of Commons — the “Mother of Parliaments” — stands a

magnificent equestrian statue of William the Conqueror. When the Norman duke

invaded England in 1066, he expropriated Saxon property, replaced Saxon

aristocratic, governmental, judicial and clerical elites and imposed Norman

laws, language and way of life on the country. Many Saxons were driven away and

many others died. Do we condemn him?

Thomas

Jefferson was an American founding father, the principal author of the

Declaration of Independence, the third president and one of the most

intelligent men of his time and perhaps all time. Yet the man who coined the

phrase “all men are created equal” believed that blacks were racially inferior

and “as incapable as children.” In his lifetime, he owned more than 600 slaves

and even fathered six children to one of them, Sally Hemming. They remained

slaves until they came of age. Do we condemn him?

Pre-contact

native North and South Americans indulged in warfare, took prisoners and kept

them as slaves for small-scale labour, where they were treated like animals:

caged, beaten, tortured and starved. John Gyles was captured in present-day

Maine in 1689 by Maliseet warriors and kept prisoner for nine years in today’s

New Brunswick. His journal provides a good description of slave life under the

natives. Do we condemn the Maliseet?

What

Hitler and his Nazi henchmen did was wrong today and wrong then: sending Jews

and many other “undesirables” to concentration camps where millions died. What

the Japanese did in creating the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere

concurrently with Hitler’s rise to power was wrong now and wrong then: invading

and conquering much of East Asia, killing thousands of non-combatants,

imprisoning Korean and Chinese females as “comfort women” to service soldiers

sexually and treating prisoners of war (including Canadians) inhumanely through

beatings, torture, starvation, denial of medicine and execution.

What

Cornwallis did would be wrong today, but it was certainly accepted practice in

18th century colonial and other warfare. Atrocities were not just perpetrated

against natives, but against white enemies as well, such as the English

fighting the Scots.

By

the treaty of 1726, the Mi’kmaq agreed not to attack any British settlements

“already made or lawfully to be made.” The founding of Halifax had the full

backing of the British government through the Board of Trade and Plantations

and was therefore legal. After meeting with Cornwallis personally, Mi’kmaq representatives

promised to be friendly with the British. But it was the Mi’kmaq who broke both

the treaty and their word when they attacked Halifax, Dartmouth and Lunenburg.

Is

it possible that the Mi’kmaq were dupes of disgruntled Acadians, egged on by

French officials who had been forced to leave mainland Nova Scotia for Cape

Breton by the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht? Or were their actions the result of

agitation by Abbé Jean-Louis Le Loutre, leader of the Acadian/Mi’kmaq

resistance against the British? In a letter to the French Minister of the

Marine, responsible for the colonies, Le Loutre wrote: “As we cannot openly

oppose the English ventures, I think that we cannot do better than to incite

the Mi’kmaq to continue warring on the English; my plan is to persuade the

Mi’kmaq to send word to the English that they will not permit new settlements

to be made in Acadia .... I shall do my best to make it look to the English as

if this plan comes from the Mi’kmaq and that I have no part in it.”

Cornwallis’s

orders in reaction to the raids were lawful at the time and he had full

authority to issue them. The 18th century was a much harsher time than our own.

Ordinary people were subject to a wide range of punishments for common crimes.

Hanging was used not only for murderers, but also against perpetrators of

property crimes. Children, youths, women and the mentally ill were not exempt

from this punishment.

Claims

of genocide of the Mi’kmaq made against Cornwallis simply do not hold up under

scrutiny. For him to attempt to exterminate the entire Mi’kmaq race, he would

have had to have jurisdiction over them. Yet Cornwallis’s authority extended

only over mainland Nova Scotia; the rest of traditional Mi’kmaq territory —

Cape Breton, Prince Edward Island, eastern New Brunswick and parts of the Gaspé

— remained firmly under French control until after Cornwallis departed.

The

proposal to remove the statue of Cornwallis or remove his name from features is

as silly as proposing the removal of the magnificent equestrian statue of

William the Conqueror outside the British House of Commons. The Thomas

Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., is one of the finest monuments in that

city. Similarly, the statue of Glooscap at Truro is a great tribute to the

Mi’kmaq Creator. I am unaware of any movements by Saxons to remove William’s

statue, Afro-Americans to dismantle the Jefferson Memorial (or change the name

of many cities named after him) or whites to take away the statue of Glooscap.

Rather

than accuse Cornwallis, the blame — if there is any — should be focused on the

laws of the times. But laws are not concrete objects, and it is much easier to

demonize an individual than a concept. We cannot simply apply today’s norms to

the past. They would be incomprehensible to 18th century Europeans, who

regarded all resources as theirs to be exploited.

After

the founding of Port Royal in 1605, European diseases — especially smallpox,

measles and tuberculosis — to which the Mi’kmaq had never before been exposed,

devastated large segments of the native population whenever they struck, and

they struck repeatedly, inflicting losses of 50 per cent or more. Additionally,

changes in the Mi’kmaq diet resulting from more European foods weakened their

resistance to common diseases they could have shrugged off earlier.

Both

French and Mi’kmaq noticed the association between contact and a decline in

native population, even if they did not initially identify the cause.

Membertou, the great Mi’kmaq chief, told Acadian chronicler Marc Lescarbot that

when he was young, his people had been “as thickly planted there as the hairs

upon his head,” but since the arrival of the French, their numbers had

diminished dramatically. The comparable course of action to removing

Cornwallis’s statue is to destroy the Port Royal Habitation near Granville

Ferry, where the French occupation of Nova Scotia started.

Additional

thousands of Mi’kmaq deaths followed as a result of the disastrous French

attempt to retake Louisbourg from the New Englanders who had captured it in

1745. The fleet sent the next year, under the Duc d’Anville, anchored at Birch

Cove in Bedford Basin, where hundreds of sick and dying Frenchmen were put

ashore to recover. Thousands of Mi’kmaq caught their diseases and spread them

throughout the province. Between one-third and one-half of the entire

aboriginal population of mainland Nova Scotia may have died during the fall and

winter of 1746-47; thousands more than were killed under Cornwallis’s edicts.

Obviously,

the only appropriate action is to dismantle Fortress Louisbourg, as its

recapture was the reason why D’Anville’s fleet came here. And while we’re at

it, let’s destroy Fort Beauséjour and any other remnants or reminders of the

European conquest and colonization of Canada. Next, let’s move on to the United

States, Central America, the Caribbean, South America and anywhere else

Europeans colonized.

I

personally deplore what happened to the Mi’kmaq, but no one can change it. If

we eradicate Cornwallis’s name, where do we ever stop?

John Boileau is the author of several books and articles about

Nova Scotia’s history.

-------------

QUOTES ABOUT HISTORY:

QUOTES ABOUT HISTORY

What should they know of the present who only the present know?

- Blair Worden

- Blair Worden

Our ignorance of history makes us slander our own times.

- Gustave Flaubert

- Gustave Flaubert

"History ought never to be confused with nostalgia. It's written

not to revere the dead, but to inspire the living. It is part of our cultural

bloodstream, the secret of who we are. And it tells us to let go of the past,

even as we honour it; to lament what ought to be lamented; and to celebrate

what should be celebrated."

- Simon Schama, "A History of Britain"

- Simon Schama, "A History of Britain"

In the end, history, especially British history with its succession of

thrilling illuminations, should be, as all her most accomplished narrators have

promised, not just instruction but pleasure.

- Simon Schama, " History of Britain"

- Simon Schama, " History of Britain"

In its Greek origins, historia meant inquiry, and from Thucydides

onwards, the past has been studied to understand its connections with the

present.

- Simon Schama

- Simon Schama

"History, Macauley says, is a debatable land. It lies on the margin

of two disputed territories; those of poetry and those of philosophy; that of

reason and that of the imagination."

- Simon Schama, introducing Thomas Macauley, "Historians of Genius"

- Simon Schama, introducing Thomas Macauley, "Historians of Genius"

"If a man were permitted to make all the ballads, he need not care

who should make the laws of a nation."

- Andrew Fletcher (1653-1716), Scottish patriot

- Andrew Fletcher (1653-1716), Scottish patriot

"We do not live in the past, but the past in us."

- Ulrich Phillips, "The Slave Economy of the Old South"

- Ulrich Phillips, "The Slave Economy of the Old South"

A generation which ignores history has no past: and no future.

- Lazarus Long, from the works of Robert Heinlein

- Lazarus Long, from the works of Robert Heinlein

To know nothing of what happened before you were born is to remain

forever a child.

- Cicero

- Cicero

There is no present or future, only the past happening over and over

again - now.

- Eugene O'Neill

- Eugene O'Neill

The present contains nothing more than the past, and what is found in

the effect is already in the cause.

- Henri Louis Bergson

- Henri Louis Bergson

Animals are molded by natural forces they do not comprehend. To their

minds there is no past and no future. There is only the everlasting present of

a single generation, its trails in the forest, its hidden pathways in the the

air and in the sea. There is nothing in the Universe more alone than Man. He

has entered into the strange world of history.

- Loren Eiseley

- Loren Eiseley

Without history we are infants. Ask what binds the British Isles more

closely to America than to Europe and only history gives a reply. Of all

intellectual pursuits, history is the most supremely useful. That is why people

crave it and need ever more of it.

- Simon Jenkins, "The London Times"

- Simon Jenkins, "The London Times"

The disadvantage of men not knowing the past is that they do not know

the present. History is a hill or high point of vantage, from which alone men

see the town in which they live or the age in which they are living.

- GK Chesterton

- GK Chesterton

A person with no sense of the past is a person who is a stranger both to

his or her own roots and to the human condition more generally. For human

beings are not creatures of nature; we are inheritors of the history that has

made us what we are. Not to know our history is not to know ourselves, and that

is the condition not of human beings, but of animals. And even from a practical

point of view, to be ignorant of the past is to make us impotent and unprepared

before the present. How can someone without a sense of medieval history have

the slightest inkling of the meaning of the current impasse the West finds

itself in in its dealings with Islam? The Crusades were not, as is often

implied by Muslims and non-Muslims alike, a unique moment of anti-Islamic

aggression. They were actually but one blip in the astonishing growth of

Islamic empires in Europe and elsewhere, from the time of Mohammed onwards,

right up to 1683 when the Turks were turned back from the gates of Vienna and

1686 when they were expelled from Budapest. But who now remembers any of this,

or ponders its consequences? It is not, needless to say, taught in National

Curriculum history, which prefers to dwell on the Aztecs, about whom we have

only the vaguest knowledge in comparison, and (endlessly) on the rise of

Fascism (not communism) in Europe, studied by pupils who know nothing of the

history of Italy and Germany before the 20th century.

Is it any wonder that, with no sense of our past or identity — as, in other moods, politicians increasingly complain — we are a culture obsessed with celebrity, football, and reality television? Most of our population know nothing else, and they have no yardstick from either history or culture with which to judge.

- Anthony O'Hear, "The Telegraph"

Is it any wonder that, with no sense of our past or identity — as, in other moods, politicians increasingly complain — we are a culture obsessed with celebrity, football, and reality television? Most of our population know nothing else, and they have no yardstick from either history or culture with which to judge.

- Anthony O'Hear, "The Telegraph"

The Crusaders have been regarded — and not only by Muslims — as an

advance force of western imperialism. This is an odd judgment, given that they

were responding to expansionist Islam. Still, the intensity of their faith, and

the brutality of some of their actions, have sat ill with liberal anti-colonialist

attitudes. There are many more eager to offer understanding to Islamic

jihadists today than to the crusaders, who had more in common with these

jihadists than either had or have with western liberals. History, however, is

not a matter of passing judgment, and real historians don't put past ages in

the dock. Their business is to show what happened and, if possible, why it

happened, to open our eyes and so enlarge our understanding. Jonathan Phillips

does this admirably. The past may be another country where they do things

differently, as L P Hartley suggested; but it is a country open for

exploration, and the voyage Phillips takes us on is fascinating.

- Allan Massie, reviewing "The Second Crusade", "The Telegraph"

- Allan Massie, reviewing "The Second Crusade", "The Telegraph"

When Cromwell instructed his portraitist to paint him ‘warts and all’,

he meant both halves of that equation. To teach the warts alone is morbid and

unhealthy.

- Mark Steyn,"The Spectator"

- Mark Steyn,"The Spectator"

The historian ought to be an educated person, writing for other educated

people about something which they don't know about, but wish to know about in a

way that they can understand.

- Sir John Keegan

- Sir John Keegan

The older I get the more I'm convinced that it's the purpose of

politicians and journalists to say the world is very simple, whereas it's the

purpose of historians to say, 'No! It's very complicated.'

The job of the historian is to help give people a sense of existence in time, without which we are really not fully human.

- David Cannadine

The job of the historian is to help give people a sense of existence in time, without which we are really not fully human.

- David Cannadine

The historian must have some conception of how men who are not

historians behave.

- from a review of the work of Edward Gibbon

- from a review of the work of Edward Gibbon

"Historians of every generation, I believe, unless they are pure

antiquarians, see history against the background — the controlling background —

of current events. They call upon it to explain the problems of their own time,

to give to those problems a philosophical context, a continuum in which they

may be reduced to proportion and perhaps made intelligible."

- Hugh Trevor Roper, valedictory address to Oxford University (1980)

- Hugh Trevor Roper, valedictory address to Oxford University (1980)

The poetry of history lies in the quasi-miraculous fact that Once, on

this earth, on this familiar spot of ground, walked other men and women, as

actual as we are today, thinking their own thoughts, swayed by their own

passions, but now all are gone, one generation vanishing after another, gone as

utterly as we ourselves shall shortly be gone like ghosts at cockcrow.

- G.M. Trevelyan

- G.M. Trevelyan

Time's glory is to calm contending kings, to unmask falsehood, and to

bring truth to light.

- Oedipus Rex

Civilization is a stream with banks. The stream is sometimes filled with

blood from people killing, stealing, shouting and doing the things historians

usually record, while on the banks, unnoticed, people build homes, make love,

raise children, sing songs, write poetry and even whittle statues. The story of

civilization is what happened on the banks.

- Will Durant,

"The History of Civilization"

Civilization is not inherited; it has to be learned and earned by each

generation anew; if the transmission should be interrupted for one century,

civilization would die, and we should be savages again.

- Will Durant, "The

Lessons of History"

Civilization is the result of human action, but not the execution of any

human design.

- Adam Ferguson, "A

History of Civil Society", 1767.

History is a record of exploded ideas.

- Admiral Fisher

- Admiral Fisher

History is an argument without end.

- Pieter Geyl

- Pieter Geyl

One can shape history as much through the facts one omits as through the

facts one includes.

- David Frum

- David Frum

History is always written wrong, and so always needs to be rewritten.

...What is interesting is brought forward as if it had been central and

efficacious in the march of events, and harmonies are turned into causes. Kings

and generals are endowed with motives appropriate to what the historian values

in their actions; plans are imputed to them prophetic of their actual

achievements, while the thoughts that really preoccupied them remain buried in

absolute oblivion.

- George Santayana,

The Life of Reason: Reason in Science, 1918

Those who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it.

- George Santayana

That men do not learn very much from the lessons of history is the most

important of all the lessons of history.

- Aldous Huxley

We learn from history that we learn nothing from history.

- George Bernard Shaw

History doesn't repeat itself, but it rhymes.

- Mark Twain

- Mark Twain

History is tangled, messy, contradictory. But is where we are.

- Eamon Duffy, "Faith of our Fathers"

- Eamon Duffy, "Faith of our Fathers"

We need open minds and open hearts when we wrestle with the past and ask

questions of it, and the answers it will provide are in nobody's pocket... We

should let nobody tell us that they know all that it contains, or try to

prescribe or constrain in advance what it has to tell us.

- Eamon Duffy, "Faith of our Fathers"

- Eamon Duffy, "Faith of our Fathers"

If history offers no obvious solutions, however, it does at least

provide the comfort of knowing that failure is nothing new.

- Eamon Duffy, from "Scandals in the Church"

- Eamon Duffy, from "Scandals in the Church"

Symbolic rearrangement of the past is of course an unavoidable aspect of

all human attempts to make sense of the present.

- Eamon Duffy

- Eamon Duffy

History is merely a list of surprises. It can only prepare us to be

surprised yet again.

- Kurt Vonnegut

- Kurt Vonnegut

Getting its history wrong is part of being a nation.

- Ernest Renan

- Ernest Renan

History is a lie agreed upon.

- Napoleon Bonaparte

- Napoleon Bonaparte

People will not look forward to posterity who never look backward to

their ancestors.

- Edmund Burke, "Reflections on the Revolution in France" (1790)

- Edmund Burke, "Reflections on the Revolution in France" (1790)

History is the torch that is meant to illuminate the past, to guard us

against the repetition of our mistakes of other days. We cannot join in the

rewriting of history to make it conform to our comfort and convenience.

- Claude G. Bowers, "The U.S. and the Spanish Civil War"

- Claude G. Bowers, "The U.S. and the Spanish Civil War"

History is what we read, write and think about the past.

- Sir Michael Howard

- Sir Michael Howard

I make no apologies for any inconsistencies or contradictions in my

essays. Those who do not change their minds in the course of a decade have

probably stopped thinking all together.

The true use of history, whether civil or military, is not to make man

clever for the next time, it is to make him wise forever.

- Sir Michael Howard,

"The Causes Of War"

People often of masterful intelligence, trained usually in law or

economics or perhaps in political science, who have led their governments into

disastrous decisions and miscalculations because they have no awareness

whatever of the historical background, the cultural universe, of the foreign

societies with which they have to deal.

- Sir Michael Howard, "The Lessons of History"

- Sir Michael Howard, "The Lessons of History"

"History is philosophy teaching by examples."

- Lord Bolingbroke, 18th century political philosopher

- Lord Bolingbroke, 18th century political philosopher

Tragedy is a tool for the living to gain wisdom — not a guide by which

to live.

- Robert Kennedy

- Robert Kennedy

History is either a moral argument with lessons for the here-and-now, or

it is merely an accumulation of pointless facts.

- Andrew Marr

- Andrew Marr

"The strife of the election is but human nature practically applied

to the facts of the case. What has occurred in this case must ever recur in

similar cases. Human nature will not change. In any future great national

trial, compared with the men of this, we shall have as weak and as strong, as

silly and as wise, as bad and as good. Let us therefore study the incidents of

this, as philosophy to learn wisdom from, and none of them as wrongs to be

revenged."

- Abraham Lincoln, looking forwards after re-election in 1864

- Abraham Lincoln, looking forwards after re-election in 1864

The best use of history is as an inoculation against radical

expectations, and hence against embittering disappointments.

- George Will, "The Pursuit of Happiness and Other Sobering Thoughts"

- George Will, "The Pursuit of Happiness and Other Sobering Thoughts"

History is a tragegy, not a morality tale.

- Isidor F Stone

- Isidor F Stone

History is what the evidence compels us to believe.

- Michael Oakshot

- Michael Oakshot

Every new generation must rewrite history in its own way.

- RG Collingwood

- RG Collingwood

What interests us about the past is at least partly a function of what

bothers us or makes us curious in the present.

- Adam Garfinkle

- Adam Garfinkle

History is past politics, and politics is present history.

- Edward Freeman

- Edward Freeman

History is the projection of ideology into the past.

- Unknown

- Unknown

Historians are not just dispassionate chroniclers. By their selection,

ordering, highlighting, attribution and analysis of facts they fashion a particular

version of the past. And they also play a part in the disputes of the present,

by legitimising or undermining the rationales, heroes and myths which influence

current debates. Historical figures are forever being conscripted for fresh

cultural battles.

- The Times, "Truth, trust and rewriting history" 4/4/02

- The Times, "Truth, trust and rewriting history" 4/4/02

Western elites — the beneficiaries of 60 years of peace and prosperity

achieved by the sacrifices to defeat fascism and Communism — are unhappy in

their late middle age, and show little gratitude for, or any idea about, what

gave them such latitude. If they cannot find perfection in history, they see no

good at all.

- Victor Davis Hanson, "Remembering World War Two", "National Review"

- Victor Davis Hanson, "Remembering World War Two", "National Review"

"The great tragedies of history occur not when right confronts

wrong but when two rights confront each other."

- Henry Kissinger

- Henry Kissinger

"History is a conversation with the dead."

- Keith Hopkins

- Keith Hopkins

"Every piece of history is a piece of human nature."

- Joss Whedon

- Joss Whedon

Peter Jones's is a vital public service. He reminds us that while we

shouldn't live in the past, we are wiser and stronger when we live with it.

- Bettany Hughes, reviewing "Vote For Caesar" by Peter Jones

- Bettany Hughes, reviewing "Vote For Caesar" by Peter Jones

History does not eliminate grievances. It lays them down like landmines.

- AN Wilson, "The Victorians"

- AN Wilson, "The Victorians"

The past is dead, and nothing that we can choose to believe about it can

harm or benefit those who were

alive in it. On the other hand, it has the power to harm us.

- ATQ Stewart, "The Shape of Irish History"

alive in it. On the other hand, it has the power to harm us.

- ATQ Stewart, "The Shape of Irish History"

If we are to understand anything of the human mind we must approach the

people of the past with humility rather than an overconfident superiority.

- ATQ Stewart, "The Shape of Irish History"

- ATQ Stewart, "The Shape of Irish History"

History is a dead thing brought to new life. It is fragments of a past,

dead and gone, resurrected by historians. It is in this sense like

Frankenstein's monster. It threatens our versions of ourselves.

- Richard White, "Remembering Ahanagran"

- Richard White, "Remembering Ahanagran"

Any good history begins in strangeness. The past should not be

comfortable. The past should not be a familiar echo of the present, for if it

is familiar why revisit it? The past should be so strange that you wonder how

you and people you know and love could come from such a time.

- Richard White, "Remembering Ahanagran"

- Richard White, "Remembering Ahanagran"

What any of us know of our births, we learn from others. It is a

beginning we ourselves cannot recall, so we commit the story to memory. We

claim it and incorporate it into our story of ourselves. We thus begin the

story of our lives with an intimate event that we can only know second hand.

And so the confusion of history and memory begins.

- Richard White, "Remembering Ahanagran"

- Richard White, "Remembering Ahanagran"

History is not the story of strangers, aliens from another realm; it is

the story of us had we been born a little earlier. History is memory; we have

to remember what it is like to be a Roman, or a Jacobite or a Chartist or even

— if we dare, and we should dare — a Nazi. History is not abstraction, it is

the enemy of abstraction.

- Stephen Fry, "History Matters"

- Stephen Fry, "History Matters"

History is not made, or lived, in hindsight.

- Eoghan Harris

- Eoghan Harris

History does not usually make real sense until long afterward.

- Bruce Catton

- Bruce Catton

One might say that history is not about the past. If you think about it,

no one ever lived in the past. Washington, Jefferson, John Adams, and their

contemporaries didn't walk about saying, "Isn't this fascinating living in

the past! Aren't we picturesque in our funny clothes!" They lived in the

present. The difference is it was their present, not ours. They were caught up

in the living moment exactly as we are, and with no more certainty of how

things would turn out than we have. History is — or should be — a lesson in

appreciation. History helps us keep a sense of proportion. Is life not

infinitely more interesting and enjoyable when one can stand in a great

historic place or walk historic ground, and know something of what happened

there and in whose footsteps you walk? Why would anyone wish to be provincial

in time, any more than being tied down to one place through life, when the

whole reach of the human drama is there to experience in some of the greatest

books ever written. History is a larger way of looking at life.

- David McCullough, from the 2003 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities

- David McCullough, from the 2003 Jefferson Lecture in the Humanities

No harm's done to history by making it something someone would want to

read.

- David McCullough

- David McCullough

By and large "history", when taken to a mass audience by a

television documentary or a newspaper, is usually only a kind of fraud, in

which viewers and readers are induced to take an interest by the promise that

people in the past were "just like us", comforted all the while by an

unspoken assumption of their own innate superiority. Most contemporary values

and nearly everything trading under the banner of modern liberalism, it seems

fair to say, are built on the notion of the past's inferiority to our own arrangements.

Queerly enough, being honest about modern life involves acknowledging that

television sets and share-option schemes are not an instant guarantee of

spiritual worth. Patronising your ancestors is simply a form of moral cheating.

Whatever we may feel about Dickens's Mr Gradgrind, he was a product of the

environment which created him. Our first duty, consequently, is to examine him

on his terms, not ours.

- DJ Taylor reviews Matthew Sweet's "Inventing The Victorians" for The Times

- DJ Taylor reviews Matthew Sweet's "Inventing The Victorians" for The Times

More and more, we are projecting our own values on to those who lived in

the past as though there can be no other way to live, or to think, than the way

we live and think now... All ages have their prejudices. We're no different. We

are different in one respect, though. Ours is the only one ever to think that

it has nothing at all to learn from the past. One result of this is that it has

become all but impossible for us to make a drama set in the past in which a

credible character doesn't think exactly like us. The writer CS Lewis called

this kind of attitude 'chronological snobbery', meaning the belief that the

latest thing is always the best. We're all chronological snobs now.

- David Quinn, "The Irish Independent"

- David Quinn, "The Irish Independent"

We must not look at the past with the enormous condescension of

posterity.

- EP Thompson

- EP Thompson

"Pearl Harbor" is strenuously respectful of contemporary

sensitivities, sometimes at the cost of accuracy.

- A.O. Scott, film critic for "The New York Times"

- A.O. Scott, film critic for "The New York Times"

Early 21st-century man prefers, like Chairman Mao, to let the past serve

the present. If he stopped making jejune moral judgments about his ancestors

and tried to understand what made them tick instead, he might make less of a

mess of his own times.

- Robert Salisbury, "The Spectator"

- Robert Salisbury, "The Spectator"

The 20th century is already slipping into the "obscurity of

mis-memory", writes Tony Judt in the introduction to this superb

collection of essays. Global capitalism has dissolved most of the old national

and ideological hatreds, leaving those under 40 puzzled as to what all the fuss

was about. History has become either a source of nostalgic reminiscence

("heritage") or a chronicle of victimhood. Politicians raid it for

"lessons"; fashion designers for styles. Gone is the sense of

carrying forward some great project, be it of national glory or social

liberation.

- Edward Skidelsky, reviewing "Reflections on the Forgotten 20th Century", "The Telegraph"

- Edward Skidelsky, reviewing "Reflections on the Forgotten 20th Century", "The Telegraph"

One of the rules of history is that people do not write about what is

too obvious to mention. And so the information, having never been recorded, is

now lost for ever.

- Michael Bywater, "Lost Worlds"

- Michael Bywater, "Lost Worlds"

Knowing what not to learn from the past is more important than knowing

what to learn.The fly sat upon the axle-tree of the chariot wheel and said

"What a dust do I raise"

- Michael Handel,

"War, Strategy & Intelligence"

He that will not apply new remedies must expect new evils; for time is

the greatest innovator.

- Francis Bacon

Telling the future by looking at the past assumes that conditions remain

constant. This is like driving a car by looking in the rearview mirror.

- Herb Brody

If men could learn from history, what lessons it might teach us! But

passion and party blind our eyes, and the light which experience gives us is a

lantern on the stern which shines only on the waves behind.

- Samuel Coleridge

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

- L. P. Hartley

The Past: Our cradle, not our prison; there is danger as well as appeal

in its glamour. The past is for inspiration, not imitation, for continuation,

not repetition.

- Israel Zangwill

- Israel Zangwill

Perhaps the most tantalising sort of history is the kind that is just

out of reach — the stories of peoples whose deeds and style of living helped to

form our own world, but of whom we know almost nothing, because they left no

written records.

- Jane Shilling, "The Times"

- Jane Shilling, "The Times"

All my life I’ve been aware of the Second World War humming in the

background. I was born 10 years after it was finished, and without ever seeing

it. It formed my generation and the world we lived in. I played Hurricanes and

Spitfires in the playground, and war films still form the basis of all my moral

philosophy. All the men I’ve ever got to my feet for or called sir had been in the

war.

- AA Gill, "The Times"

- AA Gill, "The Times"

Those who would repeat the past must control the teaching of history.

- Frank Herbert

- Frank Herbert

I had nothing but sympathy for the reporter who, after listening in

court to David Irving's insistence that the elevator to the ovens simply

couldn't have carried as many bodies as the defence expert had claimed,

confessed: 'On the way home in the train that night, to my shame, I took out a

pocket calculator and began to do some sums. Ten minutes for each batch of 25.

I tapped in. That makes 150 an hour. Which gives 3,600 for each 24-hour period.

Which gives 1,314,000 in a year. So that's fine. It could be done. Thank God,

the numbers add up.'

- DD Guttenplan, "The Holocaust On Trial"

- DD Guttenplan, "The Holocaust On Trial"

Journalism is merely history's first draft.

- Geoffrey C. Ward

- Geoffrey C. Ward

History, it used to be said, is written in four drafts. The first is the

account of a big event in the next day's newspapers. The second is the

hot-on-the-heels analysis of that event in the weekly columns. The third

becomes possible when fresh detail emerges from the memoirs and diaries of key

players. Eventually, decades later, the fourth and final draft of history is

etched in stone after all the earlier versions have been graded and revised by

learned academics with access to the archives.

In reality, this courtly ritual was never the whole story. But it barely constitutes a sub plot today. Television has transformed the rules that govern how history is made and recorded.

The judgment of posterity is no longer left to historians, or indeed the future. Today, it's the prestigious television documentary series that settles the score and sets the record straight, often while the ink is still wet on the peace treaty and the blood still visible on the combatants' hands. History is no longer written by the victors alone; even the losers can get a look in as long as they win the sympathy of the prime-time viewer.

- Liam Fay, "The Times"

In reality, this courtly ritual was never the whole story. But it barely constitutes a sub plot today. Television has transformed the rules that govern how history is made and recorded.

The judgment of posterity is no longer left to historians, or indeed the future. Today, it's the prestigious television documentary series that settles the score and sets the record straight, often while the ink is still wet on the peace treaty and the blood still visible on the combatants' hands. History is no longer written by the victors alone; even the losers can get a look in as long as they win the sympathy of the prime-time viewer.

- Liam Fay, "The Times"

For many of us, history class is a nightmare from which we are trying to

awake. Evocatively conveyed, history can be a superior form of infotainment: a

thrill-ride through the follies, triumphs and misfortunes of our ancestors. All

too often, however, the subject is reduced, by uninspiring teachers, to tedious

dates, facts and figures — the navigational co-ordinates of a forgotten world.

- Liam Fay, "The Times"

- Liam Fay, "The Times"

The book begins by pointing out that history can offer simplicity and

support to just about anybody who is willing to twist and distort its lessons.

If you believe that Man is acting out God's purpose, or progressing towards

liberal democracy, or moving towards the inevitable dictatorship of the

proletariat, you will always be able to find examples from the experience of

the past to confirm such a prejudice. Equally, if you think that history has

largely been responsible for most of the world's recent woes - and anyone

living in Ireland, Bosnia, Kashmir or the Holy Land could be forgiven for

suspecting as much - you might yearn for Man to unlearn the past. This has in

fact been tried on occasion: the Emperor Qin of China destroyed all history

books and the scholars who wrote them, vowing to start history over again - the

same nirvana that was later offered by Robespierre's new calendar, Pol Pot's

Year Zero and Chairman Mao's cultural revolution. Yet none of these attempts

worked, and Clio wreaked her own revenge on the reputation of all four

dictators. Trotsky has now been digitally restored to the photographs from

which Stalin had him airbrushed in the 1920s. Whether we like the idea of

history and its capacity for inflaming conflict or not, we are nonetheless

stuck with it.

- Andrew Roberts, reviewing Margaret McMillan's "The Uses and Abuses of History", "Standpoint"

- Andrew Roberts, reviewing Margaret McMillan's "The Uses and Abuses of History", "Standpoint"

The Somme (BBC1) was more fashionable push-me-pull-you, contrarian TV

history. Except that the belief that the battle was not so much a desperate

disaster as a postponed and expensive triumph is really more revisionist and

much closer to the official view in 1919. The Great War was the defining

tragedy of Britain, France, Germany and Russia, and a new beginning for much of

the rest of Europe. But, at the time, most of those who had been through it saw

it as a great victory; The current received wisdom of the conflict sounds like

having the history of the past 50 years recorded solely by Harold Pinter. We

are reaching the end of living contact with the Great War and it’s not a

question of “lest we forget” so much as “what we choose to remember”.

- AA Gill, reviewing a documentary in "The Times"

- AA Gill, reviewing a documentary in "The Times"

In history a great volume is unrolled for our instruction, drawing the

materials for future wisdom from the past errors and infirmities of mankind. It

may, in the perversion, serve for a magazine... supplying the means of keeping

alive, or reviving, dissesions and animosities, and adding fuel to civil fury.

History consists, for the greater part, of the miseries brought upon the world

by pride, ambition, avarice, revenge, lust, sedition, hypocrisy, ungoverned zeal,

and all the train of disorderly appetites which shake the public. These vices

are the causes... religion, morals, laws, perogatives... are the pretexts...

Wise men will apply their remedies to vices, not to names; to the causes of

evil which are permanent, not to the occasional organs by which they act, and

the transitory modes in which they appear... whilst you are discussing fashion,

the fashion is gone by. The very same vice assumes a new body... it walks

abroad, it continues its ravages, whilst you are gibbeting the carcase, or

demolishing the tomb. You are terrifying yourself with ghosts and apparitions,

whilst your house is the haunt of robbers.

- Edmund Burke, "Reflections on the Revolution in France"

- Edmund Burke, "Reflections on the Revolution in France"

Continue to instruct the world; and — whilst we carry on a poor unequal

conflict with the passions and prejudices of our day, perhaps with no better

weapons than other passions and prejudices of our own — convey wisdom to future

generations.

- Edmund Burke, in a letter to historian William Robertson

- Edmund Burke, in a letter to historian William Robertson

It is not a sin to introduce a personal bias that can be recognized and

discounted. The sin in historical composition is the organization of the story

in such a way that bias cannot be recognized.

- Herbert Butterfield, "The Whig Interpretation of History" (1931)

- Herbert Butterfield, "The Whig Interpretation of History" (1931)

It is AD 5000, and Professor Ostrich, hard at work in his study-pod on

Mars, has just made a stunning discovery. Up to that time, it had been assumed

that Ian Fleming's books about the hero James Bond, published some 3,000 years

earlier, had been fiction. But idly perusing some of the archive material that

had been saved from 'Planet' Earth, he found that the old Japanese for

'foreigner' had been 'gaijin'. This rang a bell, and on downloading You Only

Live Twice from his ear-piece into his brain, he found this was the very word

Bond had used for it too. Curious, he looked up Mount Fuji, also referred to in

that book. It existed! Becoming more and more excited, he found that 'Dunhill',

'Martini', 'White's', 'Boodles' - obviously silly names, made up for the

occasion - and even 'St James' Street' could all be attested from those

long-lost times. Incredible! Surely this must mean that the Bond stories, far

from being works of fiction, were history! And Bond, therefore, a real person!

An analogous process of reasoning has led a number of businessmen and

academics, Professor Barry Strauss of Cornell University among them, to believe

that the story Homer tells in his Iliad c 700 BC offers an accurate account of

a real war fought between Greeks and Trojans over a woman in Mycenaean times,

around 1200 BC... He solemnly adduces political reasons for Paris' abduction of

Helen (Homer gives none), dissects the military tactics of the Greeks and

Trojans (no such thing), discusses the economics and domestic politics of Troy

(non-existent) and compares it with the Hanseatic League of the late Middle

Ages (sounds of helpless laughter). Probingly, he wonders whether Achilles was

a war criminal. 'A new history', Strauss calls it, and it certainly is that. No

history ever paid so little attention to evidence or argument or any of the

usual historiographical constraints. No history has ever been so replete with

'would haves' and 'mights'. Was the Trojan king Priam able to look his soldiers

in the eye when the Greeks landed? Or would he have been too ashamed of 'his

family's policy'?

- Peter Jones, reviewing "The Trojan War" by Barry Strauss, "The Telegraph"

- Peter Jones, reviewing "The Trojan War" by Barry Strauss, "The Telegraph"

"Was there a war fought for love?"

- BBC Horizon asks the essential question of the Trojan War

- BBC Horizon asks the essential question of the Trojan War

THEORIES OF HISTORY

If the history of mankind were to begin over, without any change in the

world's surface, it would broadly repeat itself.

- Edmond Demolins

- Edmond Demolins

History followed different courses for different peoples because of

differences among peoples' environments, not because of biological differences

among peoples themselves.

- Jared Diamond, "Guns, Germs and Steel"

- Jared Diamond, "Guns, Germs and Steel"

Any study of mankind is incomplete which ignores the predominant

influence exerted on all human development, be it physical, political or

social, by man's geographic environment, and it is therefore necessary to know

something of the land in which he lived.

- Joseph Raftery, "Prehistoric Ireland"

- Joseph Raftery, "Prehistoric Ireland"

People make their own history, but they do not make it just as they

please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under

circumstances directly encountered, given, and transmitted from the past.

- Karl Marx

- Karl Marx

Athens built the Acropolis. Corinth was a commercial city, interested in

purely materialistic things. Today we admire Athens, visit it, preserve the old

temples, yet we hardly ever set foot in Corinth.

- Harold Urey

- Harold Urey

At the bidding of a Peter the Hermit millions of men hurled themselves

against the East; the words of an hallucinated enthusiast such as Mahomet

created a force capable of triumphing over the Graeco-Roman world; an obscure

monk like Luther bathed Europe in blood. The voice of a Galileo or a Newton

will never have the least echo among the masses. The inventors of genius hasten

the march of civilization. The fanatics and the hallucinated create history.

- Gustave Le Bon

- Gustave Le Bon

In Italy under the Borgias, they had 30 years of warfare,terror,murder

& bloodshed, but they produced Michelangelo, DaVinci, and the Renaissance.

In Switzerland, they had brotherly love and 500 years of democracy and peace,

and what did that produce? The Cuckoo Clock.

- Orson Welles as Harry Lime in "The Third Man"

- Orson Welles as Harry Lime in "The Third Man"

"A great man represents a strategic point in the campaign of

history, and part of his greatness consists of his being there."

- Oliver Wendell Holmes

- Oliver Wendell Holmes

Counterfactual experiments in history should always include two

limitations: the 'minimal rewrite rule' (only small and plausible changes should

be made to the actual sequence of events) and 'second order counterfactuals'

(after a certain time, the previous pattern may reassert itself).

- Geoffrey Parker, in "What If?"

- Geoffrey Parker, in "What If?"

France would pay huge reparations, enough to keep it underarmed and

angry for another generation. Anti-Semitism, ever the bane of defeated European

nations, would become a problem for it and not Germany.

- Robert Cowley, "Germany Wins The Marne" from "What If?"

- Robert Cowley, "Germany Wins The Marne" from "What If?"

QUOTATIONS FROM HISTORICAL WORKS & REVIEWS

In the second century of the Christian era, the Empire of Rome

comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of

mankind. The frontiers of that extensive monarchy were guarded by ancient

renown and disciplined valour. The gentle but powerful influence of laws and

manners had gradually cemented the union of the provinces. Their peaceful

inhabitants enjoyed and abused the advantages of wealth and luxury. The image

of a free constitution was preserved with decent reverence: the Roman senate

appeared to possess the sovereign authority, and devolved on the emperors all

the executive powers of government. During a happy period (A.D. 98-180) of more

than fourscore years, the public administration was conducted by the virtue and

abilities of Nerva, Trajan, Hadrian, and the two Antonines. It is the design of

this, and of the two succeeding chapters, to describe the prosperous condition

of their empire; and afterwards, from the death of Marcus Antoninus, to deduce

the most important circumstances of its decline and fall; a revolution which

will ever be remembered, and is still felt by the nations of the earth.

- Edward Gibbons, "The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire", 1776.

- Edward Gibbons, "The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire", 1776.

The various modes of worship, which prevailed in the Roman world, were

all considered by the people, as equally true; by the philosopher, as equally

false; and by the magistrate, as equally useful.

- Edward Gibbons, "The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire"

- Edward Gibbons, "The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire"

Who knows but that hereafter some traveller like myself will sit down

upon the banks of the Seine, the Thames, or the Zuyder Zee, where now, in the

tumult of enjoyment, the heart and the eyes are too slow to take in the

multitude of sensations? Who knows but he will sit down solitary amid silent

ruins, and weep a people inurned and their greatness changed into an empty

name?

- Volney, "Ruins"

- Volney, "Ruins"

She [the Roman Catholic Church] may still exist in undiminished vigour

when some traveller from New Zealand shall, in the midst of a vast solitude,

take his stand on a broken arch of London Bridge to sketch the ruins of St.

Paul's.

- Thomas Macauley, on Ranke's "History of the Popes"

- Thomas Macauley, on Ranke's "History of the Popes"

The Spartan, smiting and spurning the wretched Helot, moves our disgust.

But the same Spartan, calmly dressing his hair, and uttering his concise jests,

on what the well knows to be his last day, in the pass of Thermopylae, is not

to be contemplated without admiration.

- Thomas Macauley, from "The History of England"

- Thomas Macauley, from "The History of England"

"For Leonidas and for the 300 Spartan warriors who had accompanied

him, Thermopylae was more than a strategic strongpoint, it was the place where

they intended to show the world what it meant to be a Spartan. As a whole the

Greeks made a great deal of noise about the nobility of dying for your country.

But for the Spartans, it was far more than just a platitude. In battle they

were ordered to see out a beautiful death... embracing death like a lover. The

beautiful death was a sacrifice in the true sense of the word. Turning

something mortal into something sacred."

- Bettany Hughes, "The Spartans"

- Bettany Hughes, "The Spartans"

Augustus gradually increased his powers, taking over those of the

senate, the executives and the laws. The aristocracy received wealth and

position in proportion to their willingness to accept slavery. The state had

been transformed, and the old Roman character gone for ever. Equality among

citizens was completely abandoned. All now waited on the imperial command.

- Tactitus, on the transition from Republic to Empire

- Tactitus, on the transition from Republic to Empire

In Europe, the Enlightenment of the 18th century was seen as a battle

against the desire of the Church to limit intellectual freedom, a battle

against the Inquisition, a battle against religious censorship. And the victory

of the Enlightenment in Europe was seen as pushing religion away from the

center of power. In America, at the same time, the Enlightenment meant coming

to a country where people were not going to persecute you by reason of your

religion. So it meant a liberation into religion. In Europe, it was liberation

out of religion.

- Salman Rushdie, interviewed in "Reason" magazine

- Salman Rushdie, interviewed in "Reason" magazine

Michael Burleigh is not the first of them to trace the antecedents of

20th century totalitarianism to the well-documented aspiration of Jacobinism to

enclose all French people within its intellectual compass by a ruthless

stamping out of dissent in the name of progress, liberty and equality.

Jacobinism triumphant was an unedifying spectacle, and Burleigh attributes its

bloody excesses to the fanaticism of politics as religion. It is true that in

their messianic zeal for the regeneration of the French nation the Jacobins

sought to remould the minds and manners of the French people in ways that foreshadowed

Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The enduring legacy of the 18th century and the

French revolution was the demise of the assumption that had so long prevailed

in Europe that successful government required the ethical foundation that only

religion could provide. The most potent offspring of the revolution was

nationalism. Just as religion did, nationalism offered, in Burleigh’s words,

'to fulfil a human need for intense belonging'. The instrument of that

fulfilment was no longer to be the church, but the nation-state.

- Robin Stewart, reviewing "Earthly Powers" in "The Spectator"

- Robin Stewart, reviewing "Earthly Powers" in "The Spectator"

The Dutch must be understood as they really are, the Middle Persons in

Trade, the Factors and Brokers of Europe... they buy to sell again, take in to

send out again, and the greatest Part of their vast Commerce consists in being

supply'd from All Parts of the World, that they may supply All th World Again.

- Daniel Defoe, commenting on the success of the 17th century Dutch Republic

- Daniel Defoe, commenting on the success of the 17th century Dutch Republic

The wars of kings were over; the wars of peoples had begun.

- RR Palmer, describing the events of 1793

- RR Palmer, describing the events of 1793

The history of Napoleon now becomes, for 12 momentous years, the history

of mankind.

- John Holland Rose, on the outbreak of the Napoleonic wars in 1803

- John Holland Rose, on the outbreak of the Napoleonic wars in 1803

By the summer of 1807, Napoleon ran a one-man European Union with more

efficiency and less argument than achieved by Brussels 186 years later. France,

Benelux, Italy, Spain, Portugal and Germany were ruled by directives from

Napoleon's quill.

- Richard Gordon

- Richard Gordon

What finally scuppered Napoleon's Europe was of course the fatal

combination of the English Channel and the Russian winter; the same unlikely

partnership that also did for Hitler's Europe.

- Andrew Roberts, "The Telegraph"

- Andrew Roberts, "The Telegraph"

Napoleon could never imagine that some people loved their country as

much as he loved his own.

- David McCullough

- David McCullough

A healthy nation is as unconscious of its nationality as a healthy man

of his bones. But if you break a person's nationality it will think of nothing

else but getting it set again.

- George Bernard Shaw

- George Bernard Shaw

Freedom does not always win. This is one of the bitterest lessons of

history.

- A.J.P. Taylor

- A.J.P. Taylor

Rather an end in horror, than horror without end.

He could not condemn principles he might need to invoke and apply later.

The wolf cannot help having been created by God as he is, but we shoot

him all the same if we have to.

The great player in diplomacy, as in chess, asks the question,"Does

this improve me?", not look at the possible fringe benefits

If you can't have what you like, you must like what you have.

- AJP Taylor,

"The Struggle For Mastery In Europe 1848-1918"

James Sheehan commences his account amidst a peaceful fin de siècle

Europe, whose nations none the less regarded the military as the apogee of

patriotic values, and then traces the bitter 50-year process of

disillusionment. Unlike America, which has to go back to the mid-19th century

for an equivalent experience, Europeans have seen what wars can do to their own

towns and villages rather than those of other people. The two destructive

conflagrations of the first half of the 20th century, and the long armed peace

imposed by the two Cold War superpowers, have made war between Europe's

'citizen states' virtually inconceivable.

- Michael Burleigh, reviewing "The Monopoloy of Violence", "The Telegraph"

- Michael Burleigh, reviewing "The Monopoloy of Violence", "The Telegraph"

Many years ago, AJP Taylor pointed out that too much attention is paid

to how wars start, rather than the equally important question of how they end.

- Brendan Simms reviews "Poisoned Peace" by Gregor Dallas in "The Times"

- Brendan Simms reviews "Poisoned Peace" by Gregor Dallas in "The Times"

A Peace to End All Peace.

- David Fromkin, on the post WW1 settlement

- David Fromkin, on the post WW1 settlement

It is

hard to think of anything which more tragically and clearly exemplifies the

phenomenon of good political intentions achieving the precise opposite of their

aim.

- AN Wilson, on Versailles, "After The Victorians"

- AN Wilson, on Versailles, "After The Victorians"

The reorganization of the map of Europe at Versailles did not solve

anything except maybe sowing the seeds of the next war. To give justice to

those who wanted to redraw the European borders for them to be more consistent

to the ethnic picture, it should be added here that it was an impossible

task. There was no possibility of creating viable states without

incorporating ethnic minorities within them. In all of Europe, but especially

in the eastern half, the ethnic communities were so intertwined that there was

no logical way to disentangle them.

- EG Ban

- EG Ban

One consequence of the continuing and unhealthy fascination in this

country with the Third Reich has been an ignoring of the Second, whose Faustian

story had yet more terrible consequences. At the beginning of the last century

Germany could claim to lead the world; not only in industry, science and

technology, but in what she proudly termed Kultur: philosophy, poetry, music,

philology, historiography, law. As a welfare state Bismarck had provided a

model that Britain was only beginning to follow a generation later. Germany’s

constitution may have given too little power to the legislature to suit

Anglo-Saxon tastes, but few people complained: the French, after all, gave

rather too much. Yet 40 years later the German nation was in the grip of a

psychopath who led her to utter disaster. So what went wrong? What went wrong,

of course, was that Germany lost the first world war — a war, most historians

agree, that, if she did not provoke, she did nothing to prevent, and which she

fought in a manner that ultimately left her friendless.

- Michael Howard, from his review of "The War Lords" in "The Spectator"

- Michael Howard, from his review of "The War Lords" in "The Spectator"

It is a strange irony that the war-winning weapons that emerged from the

First World War were subsequently neglected by the states that had invented

them - but were seized on and developed by the opposition. Thus Britain's

secret weapon, the tank, was enthusiastically taken up by the Wehrmacht,

leading to the Nazi Blitzkrieg; while the heavy four-engined bomber - unleashed

against London in 1917 - was forgotten as Germany's Luftwaffe concentrated on

light, short-range planes such as the Stuka. Instead it was left to the RAF to

develop such heavy-lifting blockbusters as the Lancaster which so devastated

Germany's cities in 1943-45. By comparison, the 1940-41 London Blitz was a

flesh wound. Both the Blitz and Bomber Command's answering offensive - the wind

and the whirlwind in Arthur 'Bomber' Harris's evocative phrase - grew out of

the first sustained attempt to destroy a city from the air: the raids by the

aptly named Giant and Gotha bombers of Germany's England Squadron that are the

subject of Neil Hanson's engrossing and eye-opening book.

The first sorties were mounted over eight successive nights in 1917. The following summer, as the war on the Western Front reached its climax, the bombers were back - this time armed with a fearsome new weapon - the Elektron bomb, an incendiary deliberately designed to create a city-consuming firestorm to rival Pepys's conflagration in 1666. Fortunately for London, the bombs were too unreliable, the bombers too few in number, and the London air defences - belatedly set up after the Zeppelin raids of 1916 - too effective, for the 'Fire Plan', as the Germans called their raid, to have the desired effect. The dead totalled 835, and the damage was similarly limited. However, both sides drew lessons from the brief campaign, even if they were the wrong ones. The British, paralysed by fear of what devastation future raids might bring, backed Chamberlain's craven appeasement policy and sank resources into both Bomber Command and co-ordinated air defences - guns, gas masks, searchlights, balloons, shelters and, above all, radar, the Spitfire and the Hurricane. The Germans, concluding after 1918 that the big bomber could not deliver the desired total destruction, failed to build the sort of planes that would reduce their own cities to ashes. They were hoist by their own petard.

- Nigel Jones, reviewing "First Blitz" by Neil Hanson, "The Telegraph"

The first sorties were mounted over eight successive nights in 1917. The following summer, as the war on the Western Front reached its climax, the bombers were back - this time armed with a fearsome new weapon - the Elektron bomb, an incendiary deliberately designed to create a city-consuming firestorm to rival Pepys's conflagration in 1666. Fortunately for London, the bombs were too unreliable, the bombers too few in number, and the London air defences - belatedly set up after the Zeppelin raids of 1916 - too effective, for the 'Fire Plan', as the Germans called their raid, to have the desired effect. The dead totalled 835, and the damage was similarly limited. However, both sides drew lessons from the brief campaign, even if they were the wrong ones. The British, paralysed by fear of what devastation future raids might bring, backed Chamberlain's craven appeasement policy and sank resources into both Bomber Command and co-ordinated air defences - guns, gas masks, searchlights, balloons, shelters and, above all, radar, the Spitfire and the Hurricane. The Germans, concluding after 1918 that the big bomber could not deliver the desired total destruction, failed to build the sort of planes that would reduce their own cities to ashes. They were hoist by their own petard.

- Nigel Jones, reviewing "First Blitz" by Neil Hanson, "The Telegraph"

"How would the British and American publics have responded, if

early in 1945 they had been told that the bomber forces had been stood down,

while German and Japanese troops were still fighting furiously to kill Allied

soldiers?"

- Michael Howard

- Michael Howard

"A simple survey of the records show that between twenty and

twenty-five million people perished in World War II and more of them in the

later years than in the earlier years. Every month by which the war was

shortened would have meant saving of the order of half a million to a million

lives. Among those granted life would have been my brother Joe, killed in

October 1944 in the Battle for Italy. What a difference it would have made if

the critical date (of the atomic bomb's first use in the war) had been not

August 6, 1945, but August 5, 1943."

- John Archibald Wheeler

- John Archibald Wheeler

The kamikazes... exacted a terrible cost. Some 2800 kamikaze attacks

killed nearly 5000 Americans and wounded 4800 more. Ominously, Japan had

reserved more than 5000 suicide aircraft to be used against the expected

invasion of the home islands. A gruesome scenario that would have magnified the

immense human toll of the kamikaze.

- from "The History Channel: Dogfights"

- from "The History Channel: Dogfights"

The book uses personal accounts to illuminate the effects of policy

decisions. It includes a generous number of Asian voices, Filipino and Chinese

as well as Japanese, which provide a sense of overwhelming American

technological and industrial superiority – "assault by abundance" –

and the ultimate futility of Japanese resistance. In describing systematic

Japanese brutality towards both Allied prisoners and fellow Asians, Hastings is

also careful to shade the coin, showing that not all Japanese were sadists. But

if today some of them suggest such inhumanity was no worse than the Allied

bombing, he notes that having started the war, they "waged it with such

savagery towards the innocent and impotent that it is easy to understand the

rage which filled Allied hearts in 1945". He makes clear the scale and

horror of Japanese atrocities, their strategic myopia and military ineptitude –

and the effects of these on Allied decision-making. Of the invasion of Okinawa,

Hastings notes that the Japanese reasoned that if the US could be made to pay

dearly enough for winning a single offshore island, America's leaders would be

put off attacking the main ones. "They were correct in their analysis, but

utterly deluded about its implications." The horror of the atomic bombs is

put in context by the description of the firebomb raid on Tokyo of March 9,

1945, in which as many as 100,000 people died. And the significance of aerial

bombardment is put in context with the submarine campaign that effectively

crippled Japan's economy. He does not dwell on the effects of the bombs

themselves, but describes the inevitability of their use in balanced terms.

- Jon Latimer, reviewing "Nemesis: The Battle for Japan" by Max Hastings, "Telegraph"

- Jon Latimer, reviewing "Nemesis: The Battle for Japan" by Max Hastings, "Telegraph"

Ian Kershaw makes the point that, of Churchill, Hitler, Mussolini,

Konoe, Tojo, Stalin and Roosevelt, the last was the only one constrained and

guided by public opinion. His eye was constantly on the polls, and his

decisions were weighted, trimmed and timed in accordance with them. By

contrast, Britain’s decision to fight on was taken by five men — Churchill,

Chamberlain, Halifax, Attlee and Greenwood; they did not pause to consult public

opinion even if, perhaps, they did think they reflected it. On the other hand,

Roosevelt was surprised that Churchill found it necessary to keep his Cabinet

informed and seek its approval of what was going on in the discussions at

Placentia Bay in 1941. Roosevelt’s Cabinet probably did not even know where the

president was at the time.

- Noble Frankland, reviewing Kershaw's "Fateful Choices", "The Spectator"

- Noble Frankland, reviewing Kershaw's "Fateful Choices", "The Spectator"

It was a crucial victory for liberal democracy, the very system that had

seemed to be on the brink of destruction four years earlier. It was that system

that Hitler and others had blamed for plunging the world into the Great

Depression, and which he promised to crush by defeating the liberal democracies

and their "Jewish capitalist warmonger" allies. To Hitler, Britain

and America represented a way of life that was decadent, corrupt, and grossly

self-serving — precisely the same complaints voiced by Osama bin Laden and

today's Islamic terrorists. And it was a way of life that in the fall of 1940

seemed about to pass into history.

It is important to remember how many people, especially Europeans, wanted democracy to lose and hoped Hitler would win. They included the world's Communist parties, who followed the directions of their leader Josef Stalin in enthusiastically embracing his alliance with Nazi Germany. They included politicians and intellectuals who, after Hitler's lightning victories in Poland and France, saw a new world order arising and wanted to be part of it. Today, it is sobering to contemplate how close Hitler came in the early summer of 1941 to achieving that new order.

- Arthur Herman, commenting on World War Two for America's "National Review"

It is important to remember how many people, especially Europeans, wanted democracy to lose and hoped Hitler would win. They included the world's Communist parties, who followed the directions of their leader Josef Stalin in enthusiastically embracing his alliance with Nazi Germany. They included politicians and intellectuals who, after Hitler's lightning victories in Poland and France, saw a new world order arising and wanted to be part of it. Today, it is sobering to contemplate how close Hitler came in the early summer of 1941 to achieving that new order.

- Arthur Herman, commenting on World War Two for America's "National Review"

The Nazi occupation of Europe is not often considered in imperial terms

- probably because it was so short-lived, but also because it does not

correspond to our usual concept of empires, in that it sought to dominate and

reshape continental Europe rather than exploit overseas territories.

By the end of 1942, the Nazis controlled approximately one-third of the European land mass and half its inhabitants, and Hitler personally appointed the officials who ran these territories. Nobody since Napoleon ever held such sway. But it was also a product of the imperialism of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and for that reason bears scrutiny as such... The overriding impression created by Mark Mazower's overview of the political and economic basis of their imperial plans is one of monumental stupidity. Germany faced a severe manpower crisis during the war but, blinded by their racial prejudices, they implemented measures that only made things worse... Germany was so short of workers to replace men conscripted to fight that the Nazis had to resort to impressment of hundreds of thousands of foreigners, making a mockery of their racial attitudes and ultimately proving counter-productive. Between 1939 and 1944 they shrunk the German labour force from 39 to 29 million... In the end, Germany could have racial purity or imperial dominion, but it could not have both.

- Jon Latimer reviews "Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe", "The Telegraph"

By the end of 1942, the Nazis controlled approximately one-third of the European land mass and half its inhabitants, and Hitler personally appointed the officials who ran these territories. Nobody since Napoleon ever held such sway. But it was also a product of the imperialism of the 19th and early 20th centuries, and for that reason bears scrutiny as such... The overriding impression created by Mark Mazower's overview of the political and economic basis of their imperial plans is one of monumental stupidity. Germany faced a severe manpower crisis during the war but, blinded by their racial prejudices, they implemented measures that only made things worse... Germany was so short of workers to replace men conscripted to fight that the Nazis had to resort to impressment of hundreds of thousands of foreigners, making a mockery of their racial attitudes and ultimately proving counter-productive. Between 1939 and 1944 they shrunk the German labour force from 39 to 29 million... In the end, Germany could have racial purity or imperial dominion, but it could not have both.

- Jon Latimer reviews "Hitler's Empire: Nazi Rule in Occupied Europe", "The Telegraph"

One single Anne Frank moves us more than countless others who suffered

just as she did, but whose faces have remained in the shadows. Perhaps it is

better that way; if we were capable of taking in all the suffering of all those

people, we would not be able to live.

- Primo Levi

- Primo Levi

World War II proved a hypothesis that Alexis de Tocqueville advanced a

century before: the war-fighting potential of a democracy is at its greatest

when war is most intense; at its weakest when war is most limited. This is a

lesson with enduring relevance to our own times — and our own wars.

- David Frum, "National Review"

- David Frum, "National Review"

They fought on with a devotion which would puzzle the generation of the

1980s. More surprising, in many instances it would have baffled the men they

themselves were before Pearl Harbor. Among MacArthur's ardent infantrymen were

cooks, mechanics, pilots whose planes had been shot down, seamen whose ships

had been sunk, and some civilian volunteers.

- William Manchester, on the US defence in Bataan against the Japanese

- William Manchester, on the US defence in Bataan against the Japanese

Vichy proves one thing: if you don’t want to know how low your fellow

citizens can fall, and crawl, don’t lose a war.

- Frederic Raphael reviews "Verdict on Vichy" by Michael Curtis for The Times

- Frederic Raphael reviews "Verdict on Vichy" by Michael Curtis for The Times

The victory of liberalism enables them to sue their victors.

- Hugh Trevor Roper, commenting on the Nazis